Construction of Rockefeller Center

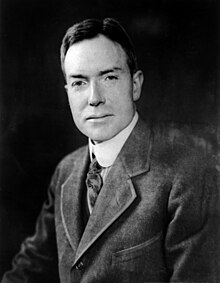

The construction of New York City's Rockefeller Center complex was conceived as an urban renewal project, spearheaded by John D. Rockefeller Jr., to help revitalize midtown Manhattan. The project was envisioned as a new opera house complex for the Metropolitan Opera, but the opera-house plans were canceled and the project was changed to an office-building and mass-media complex. Rockefeller Center was built on former Columbia University property bounded by Fifth Avenue to the east, Sixth Avenue to the west, 48th Street to the south, and 51st Street to its north. The core of the complex was built between 1931 and 1940 at a cost equivalent to $2,217,000,000 in 2023 dollars. However, some of Rockefeller Center's buildings were not completed until the 1970s. The center spans 22 acres (8.9 ha) in total, with some 17 million square feet (1.6×106 m2) in office space.

In the early 1900s, Columbia University moved to Morningside Heights. By the 1920s, Fifth Avenue was a prime site for development. The Metropolitan Opera was looking for new sites for its opera house around that time, and Benjamin Wistar Morris, who was deciding on sites for the new facility, decided on the former Columbia site.

Rockefeller eventually became involved in the project, and in 1928, leased the site from Columbia for 87 years. Rockefeller's lease excluded land along the east side of Sixth Avenue, to the west of the Rockefeller property, as well as at the site's southeast corner. Rockefeller hired Todd, Robertson and Todd as design consultants, and selected Corbett, Harrison & MacMurray; Hood, Godley & Fouilhoux; and Reinhard & Hofmeister as architects for the new opera complex. However, the opera was unsure about moving to the new complex, and the Wall Street Crash of 1929 put an end to the plans. Rockefeller instead entered negotiations with the Radio Corporation of America (RCA) to create a new mass-media complex on the site. A new plan was released in January 1930, and an update to the plan was presented after Rockefeller obtained a lease for the land along Sixth Avenue. Revisions continued until March 1931, when the current site design was unveiled. A late change to the proposal included the complex of internationally themed buildings along Fifth Avenue.

All of the buildings in the original complex were designed in the Art Deco architectural style. Excavation of the site started in April 1931, and construction of the first buildings started in September of the same year. The first building was opened in September 1932, and most of the complex was completed by 1935. The final three buildings in the original complex were built between 1936 and 1940, although the Rockefeller Center was officially completed by November 2, 1939. The construction project employed over 40,000 people and was considered the largest private building project at the time.

Since then, there have been several modifications to the complex. An additional building at 75 Rockefeller Plaza was constructed in 1947, while a building at 600 Fifth Avenue was constructed in 1952 and later became part of the complex. Four buildings were built along the west side of Sixth Avenue in the 1960s and 1970s, comprising the most recent expansion of Rockefeller Center. One structure in the original complex, the Center Theatre, was demolished in 1954.

Site

The first colonial claim over the current Rockefeller Center's site was by the Dutch Republic in the 1620s, who made the entire island of Manhattan a part of New Netherland. In 1664, the British took ownership of the island, and in 1686, much of Manhattan, including the future Rockefeller Center site, was established as a "common land" of the city of New York.[1] The land remained in city ownership until 1801, when the physician David Hosack, a member of the New York elite, purchased a patch of land in what is now Midtown for $5,000,[2] equivalent to $112,000 in 2023 dollars.[3] In terms of the present-day street grid, Hosack's land was bounded by 47th Street on the south, 51st Street on the north, and Fifth Avenue on the east, while the western boundary of the land was slightly east of Sixth Avenue.[1][2] Hosack opened the Elgin Botanic Garden, the country's first botanical garden,[4] on the site in 1804.[5][6] The gardens would operate until 1811,[7] when Hosack put it on sale for $100,000 (equivalent to $2,141,000 in 2023[3]). As no one was willing to buy the land, the New York State Legislature eventually bought the land for $75,000 (equivalent to $1,606,000 in 2023[3]).[1][8][9]

In 1814, the trustees of Columbia University (then Columbia College) were looking to the state legislature for funds when the legislature unexpectedly gave Hosack's former land the college instead.[1] The gardens became part of Columbia's "Upper Estate" (as opposed to the "Lower Estate" in Lower Manhattan), on the condition that the college move its entire campus to the Upper Estate by 1827.[8] Although the relocation requirement was repealed in 1819,[8] Columbia's trustees did not see the land as "an attractive or helpful gift", so the college let the gardens deteriorate instead.[9][10] The area would not become developed until the 1830s, and the land's value did not increase to any meaningful amount until the late 1850s, when the St. Patrick's Cathedral was built nearby, spurring a wave of development in the area.[11] Ironically, the cathedral was built because it faced the Upper Estate gardens.[10] By 1860, the Upper Estate contained four row houses below 49th Street as well as a wooden building across from the cathedral. The surrounding area was underdeveloped, with a potter's field and the railroad lines from Grand Central Depot located to the east.[8]

Columbia built a new campus near its Upper Estate in 1856, selling a plot at Fifth Avenue and 48th Street to the St. Nicholas Church to pay for construction.[10] Shortly afterward, Columbia implemented height restrictions that prevented any taller buildings, such as apartment blocks or commercial and industrial buildings, from being built on its property.[12][8] Narrow brownstone houses and expensive "Vanderbilt Colony" mansions were built on nearby streets, and the area became synonymous with wealth. By 1879, there were brownstones on every one of the 203 plots in the Upper Estate, which were all owned by Columbia.[8][10][12][13]

The construction of the Sixth Avenue elevated line in the 1870s made it easy to access commercial and industrial areas elsewhere in Manhattan.[8] However, it also drastically reduced property values, and Columbia sold the southernmost block of its Midtown property in 1904, using the $3 million sale price (equivalent to $79,568,000 in 2023[3]) to pay for newly acquired land in Morningside Heights even further uptown, replacing its Lower Estate.[10][12][13] Simultaneously, the low-lying houses along Fifth Avenue were being replaced with taller commercial developments, and the widening of the avenue between 1909 and 1914 contributed to this transition.[14] Columbia also stopped enforcing its height restriction, which the writer Daniel Okrent describes as a tactical mistake for the college because the wave of development along Fifth Avenue caused the Upper Estate to become available for such redevelopment.[15] John Tonnele, the university's real estate adviser, was hired to find suitable tenants for the land, since the leases on the Upper Estate rowhouses were being allowed to expire without renewal.[16][17]

Early plans

New Metropolitan Opera House

In 1926, the Metropolitan Opera started looking for locations to build a new opera house to replace the "Old Met" at 39th Street and Broadway.[20][18] This was not a new effort, as Otto Kahn, the opera's president, had been seeking to erect new opera house since he assumed the position in 1908.[21][22] However, Kahn did not have money to fund the new facility itself, and his efforts to solicit funding from R. Fulton Cutting, the wealthy and influential Cooper Union president, were unsuccessful.[23][24] Cutting did support the 1926 proposal for a new building, as did William Kissam Vanderbilt.[16] By summer 1927, Kahn had hired architect Benjamin Wistar Morris and designer Joseph Urban to come up with blueprints for the opera house.[14][16][19] They created three possible blueprints, which the opera company all rejected.[14]

Kahn wanted the opera house to be located on a relatively cheap piece of land near a busy theater and retail area, with access to transportation.[16] In January 1928, Tonnele approached Cutting to propose the Upper Estate as a possible location for the opera house.[25][26] Cutting told of Tonnele's idea to Morris, who thought that the Columbia grounds in Midtown were ideal for the new opera house.[7][27] By spring 1928, Morris had created a blueprint for an opera house and a surrounding retail complex at the Upper Estate.[14][28][29] However, the new building was too expensive for the opera to fund by itself, and it needed an endowment. On May 21, 1928, Morris presented the project during a dinner for potential investors, at which the Rockefeller family's public relations adviser Ivy Lee was a guest. Lee later informed his boss, John D. Rockefeller Jr., about the proposal, to which the latter showed interest.[30][31][32] Rockefeller wished to give the site serious consideration before he invested, and he did not want to fund the entire project on his own. As a result, in August 1928, Rockefeller contacted several firms for advice.[33] Rockefeller ended up hiring the Todd, Robertson and Todd Engineering Corporation as design consultants to determine the project's viability,[34][35][36] with one of the firm's partners, John R. Todd, serving as the principal builder and managing agent for the massive project.[37][38] Todd submitted a plan for the opera house site in September 1928, in which he proposed constructing office buildings, department stores, apartment buildings, and hotels around the new opera house.[39][40]

Charles O. Heydt, one of Rockefeller's business associates, met with Kahn in June 1928 to discuss the proposed opera house.[41][42] After the meeting, Heydt purchased land just north of the proposed opera site as per Rockefeller's request, but for a different reason: Rockefeller was afraid that many of the landmarks of his childhood, located in the area, were going to be demolished by the 1920s wave of development.[42] In fact, Rockefeller's acquisition of the land might have been more for the family name rather than for the opera proposal itself, as Rockefeller never mentioned the details of the proposal in his constant daily communications with his father, John D. Rockefeller Sr.[43]

In the summer of 1928, the Opera and Rockefeller were named as prospective buyers for the Columbia site.[5] A lease agreement was made in fall 1928, and the lease was signed on December 31 of that year.[41][44] Columbia leased the plot to Rockefeller for 87 years at a cost of over $3 million per year (equivalent to $42,065,000 in 2023[3]), thereby allowing all the existing leases on the site to expire by November 1931 so Rockefeller could purchase them.[45] Rockefeller would pay $3.6 million per year (equivalent to $50,478,000 in 2023[3]). In return, he would be entitled to the income from the property, which at the time was about $300,000 annually (equivalent to $4,207,000 in 2023[3]).[46] This consisted of a 27-year lease for the site from Columbia, with the option for three 21-year renewals, such that the lease could theoretically last until 2015.[40][44][47][48] Moreover, Rockefeller could avoid any rent increases for forty-five years, even when adjusted for inflation.[49] The lease did not include the 100-foot-wide (30 m) strip of land bordering Sixth Avenue on the west side of the plot, as well as another property on Fifth Avenue between 48th and 49th Streets, and so were excluded from the plans.[5][50] Simultaneous with the signing of the lease, the Metropolitan Square Corporation was created to oversee construction.[40][41]

Architects

In October 1928, before the lease had been finalized, Rockefeller started asking for recommendations of architects.[51] By the end of the year, Rockefeller hosted a "symposium" of architectural firms so he could solicit plans for the new complex. He invited seven firms, six of which specialized in Beaux-Arts architecture, and tasked the noted Beaux-Arts architects John Russell Pope, Cass Gilbert, and Milton B. Medary to judge the proposals.[39][51][52] Rockefeller requested that all the plans be submitted by February 1929,[52][53] and the blueprints were presented in May of that year.[53][54] All of the proposals called for rentable space of 4 to 5 million square feet (0.37×106 to 0.46×106 m2), but these plans were so eccentric that the board rejected all of them.[40][55][56] Morris was retained for the time being until a more suitable architect could be found.[57] However, by the end of 1928, Morris had been fired without pay.[58] He was eventually paid $50,000 for his contributions to the project, and many of his ideas were included in the final product.[59]

Rockefeller retained Todd, Robertson and Todd as the developers of the proposed opera house site,[34] and as a result, Todd stepped down from the Metropolitan Square Corporation's board of directors.[60] In October 1929,[55] Todd appointed Corbett, Harrison & MacMurray; Hood, Godley & Fouilhoux; and Reinhard & Hofmeister, to design the buildings. They worked under the umbrella of "Associated Architects" so none of the buildings could be attributed to any specific firm.[30][35][61][62] The lead architect and the foremost member of the Associated Architects was Raymond Hood,[63][64] who would become memorable for his creative designs.[65] Hood, along with Harvey Wiley Corbett, were retained as consultants.[63] The team included also Wallace Harrison, who would later become the family's principal architect and adviser to John Rockefeller Jr.'s son Nelson.[66][67] Hood, Morris, and Corbett were the consultants on "architectural style and grouping", although Morris was in the process of being fired.[68] Todd also hired L. Andrew Reinhard and Henry Hofmeister as rental or tenant architects, who designed the floor plans for the complex[69][70] and were known as the most pragmatic of the Associated Architects.[65] Hood, Corbett, Harrison, Reinhard, and Hofmeister were generally considered to be the principal architects.[40][71] They mostly communicated with Todd, Robertson and Todd, rather than with Rockefeller himself.[64]

Hugh Ferriss and John Wenrich were hired as "architectural renderers" who produced drawings of the proposed buildings based on the Associated Architects' blueprints.[64] Rene Paul Chambellan was also commissioned to sculpt the models of the buildings, though he would later create some of the art for the center.[72]

Original plan and failure

The Metropolitan Opera held a dilatory position toward the development, and they refused to take up the site's existing leases until they were certain that they had enough money to do so.[45][73] In January 1929, Cutting unsuccessfully asked Rockefeller for assistance in buying the leases. Since the opera would not have any funds until after they sold the Old Met by April of that year, Heydt suggested that the Metropolitan Square Corporation buy the leases instead, in case the opera ultimately did not have money to relocate.[74] The opera felt that the cost of the new opera house would far exceed the potential profits. They wanted to sell their existing facility and move into the proposed new opera house by 1931, which meant that all existing leases would need to be resolved by May 1930. Otherwise, the facility could not be mortgaged, and Columbia would retake ownership of the land, which would be a disadvantage to both the opera and Rockefeller.[75]

In August 1929, Rockefeller created a holding company to purchase the strip of land on Sixth Avenue that he did not already lease,[76] so he could build a larger building on the site and maximize his profits (see § Land acquisition and clearing).[46] The company was called the Underel Holding Corporation because the land in question was located under the Sixth Avenue Elevated.[77][78][79]

By October 1929, Todd announced a new proposal that differed greatly from Morris's original plan.[58] Todd suggested that the site's three blocks be further subdivided into eight plots, with an "Opera Plaza" in the middle of the center block. The complex would contain the Metropolitan Opera facility as well as a retail area with two 25-story buildings; department stores; two apartment buildings; and two hotels, with one rising 37 stories and the other being 35 stories.[80][81] The opera would have been located on the center block between 49th and 50th Streets east of Sixth Avenue.[45][81] The retail center would be built around[50] or to the west[81] of the Opera Building, in a layout similar to that of the English town of Chester.[45]

The main hurdle to the plan was the opera's reluctance to make a commitment to the development by buying leases.[73][45] Rockefeller stood to lose $100,000 per year (equivalent to $1,402,000 in 2023[3]) if he leased the new opera house.[82] Todd had objected that the opera house would be a blight rather than a benefit for the neighborhood, as it would be closed most of the time.[34][83] After the stock market crash of 1929, these concerns were invalidated by the fact that the Metropolitan Opera could not afford to move anymore.[40][84][35] The opera instead suggested that Rockefeller pay for half for the old opera house and the land under it, an offer that Rockefeller refused.[83][85] On December 6, 1929, the plans for the new opera house were abandoned completely.[45][85][86]

New plans

With the lease still running, Rockefeller had to devise new plans quickly so that the site could become profitable. Hood came up with the idea to negotiate with the Radio Corporation of America (RCA) and its subsidiaries, National Broadcasting Company (NBC) and Radio-Keith-Orpheum (RKO), to build a mass media entertainment complex on the site.[87][88] This was achievable because Wallace Harrison was good friends with Julian Street, a Chicago Tribune reporter whose wife's great-uncle Edward Harden was part of the RCA board of directors. At Hood's request, Harrison made a lunch date to tell Street about the mass-media complex proposal.[89][90] Harden, in turn, described the idea to RCA's founder Owen D. Young, who was amenable to the suggestion.[89][91] It turned out that Young, a longtime friend of Rockefeller's, had been thinking of constructing a "Radio City" for RCA for several years.[92] Rockefeller later stated, "It was clear that there were only two courses open to me. One was to abandon the entire development. The other to go forward with it in the definite knowledge that I myself would have to build it and finance it alone."[34][93]

In January 1930, Rockefeller tasked Raymond Fosdick, the Rockefeller Foundation's future head, with scheduling a meeting with Young. The RCA founder was enthusiastic about the project, expressing his vision for a complex that, according to Daniel Okrent, contained "an opera house, a concert hall, a Shakespeare theater—and both broadcast studios and office space for RCA and its affiliated companies".[94] RCA president David Sarnoff would join the negotiations in spring 1930.[95] Sarnoff immediately recognized Radio City's potential to impact the fledgling television and radio industries.[92] By May, RCA and its affiliates had made an agreement with Rockefeller Center managers. RCA would lease 1 million square feet (0.093×106 m2) of studio space; get naming rights to the development's largest tower; and develop four theaters, at a cost of $4.25 million per year (equivalent to $61,716,000 in 2023[3]).[40][95] NBC was assured exclusive broadcasting rights at Rockefeller Center as part of the deal.[96]

RCA media complex proposals

Todd released a new plan called G-3 in January. Like the previous Metropolitan Opera proposal, this blueprint subdivided the complex into eight blocks with a plaza in the middle of the center block. It was similar to his October 1929 plan for the Opera, with one major change: the opera house was replaced with a 50-story building.[40][80][97] The 50-story tower was included because its larger floor area would provide large profits, and its central location was chosen because Todd believed that the center of the complex was too valuable to waste on low-rise buildings.[98] Plans for a new Metropolitan Opera building on the site were still being devised, including one proposal to place an office building over the opera facility. However, this was seen as increasingly unlikely due to the opera's reluctance to move to the complex.[99] A proposal to create roads that crossed the complex diagonally was briefly considered, but it was dropped because it involved deleting city streets, which in turn could only be done after lengthy discussions with city officials.[87] Plan G-3 was presented to the Metropolitan Square Corporation's managers in February.[100] At the time, Todd thought that G-3 was the most viable proposal for the complex.[101]

Another plan called H-1 was revealed in March 1930, after the Underel Corporation had acquired the land near Sixth Avenue.[40][102] The leases for the newly acquired land contained specific stipulations on how it was to be used.[103] Under this new proposal, there would be facilities for "television, music, radio, talking pictures and plays."[104] RCA planned to build theaters on the north and south blocks near Sixth Avenue, with office buildings above the theaters' Sixth Avenue sides. The theater entrances would be built to the west along Sixth Avenue, and the auditoriums would be located to the east, since the city's building code prohibited the erection of structures over the auditoriums of theaters. The delivery lane was eliminated in this plan because it was seen as unnecessary, what with the road facing the blank walls of the theaters instead of the windows of department stores.[105] The complex would also contain three tall buildings in the center of each block, including a 60-story building in the center block for RCA (the current 30 Rockefeller Plaza).[106] Todd suggested that this large tower be placed at Sixth Avenue because the Sixth Avenue Elevated would have reduced the value of any other properties at the west end of the complex.[107] At Fifth Avenue there would be a short oval-shaped retail building, whose top floors would be occupied by Chase National Bank offices. There would be a plaza between the oval building and RCA's building, and a restaurant atop the former.[106][108] A transcontinental bus terminal would be built underground to entice tenants who might otherwise rent near Penn Station or Grand Central.[109]

Plan H-1 was approved in June 1930.[109] In the middle of the month, The New York Times announced the plans for the "Radio City" project between 48th Street, 51st Street, Fifth Avenue, and Sixth Avenue. Additional details were released: for example, the $200 million cost projection for the three skyscrapers (equivalent to $2,904,000,000 in 2023[3]).[110] To provide space for the plaza, 49th and 50th Streets would be relocated to underground tunnels, and there would be parking structures both aboveground and underground, while the streets surrounding the plot would be widened to accommodate the heavy traffic loads.[106] Four theaters would also be built: two small theaters for television, comedy, and drama; a larger one for movies; and another theater, larger still, for vaudeville.[110][111][112] Under the plan, the demolition of the site's existing structures would start in the fall, and the complex would be complete by 1933.[106] This plan had not been disclosed to the general public prior to the announcement, and even John Rockefeller Jr. was surprised by the $350 million cost estimate (equivalent to $5,082,000,000 in 2023[3]), since a private project of this size was unprecedented.[113]

Since Rockefeller had invested large sums of money in the stock market, his wealth declined sharply as a result of the 1929 stock market crash.[114] In September 1930, Rockefeller and Todd started looking for funding to construct the buildings, and they secured a tentative funding agreement with the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company by November. In March 1931, this agreement was made official, with Metropolitan Life agreeing to lend $65 million (equivalent to $944,000,000 in 2023[3]) to the Rockefeller Center Development Corporation.[115][116] Metropolitan Life's president Frederick H. Ecker granted the money on two conditions: that no other entity grant a loan to the complex, and that Rockefeller co-sign the loan so that he would be responsible for paying it off if the development corporation defaulted.[116] Rockefeller covered ongoing expenses through the sale of oil company stock.[48] Other estimates placed Radio City's cost at $120 million (equivalent to $1,743,000,000 in 2023[3]) based on plan H-16, released in August 1930, or $116.3 million (equivalent to $1,689,000,000 in 2023[3]) based on plan F-18, released in November 1930.[117]

Design influences

The design of the complex was affected greatly by the 1916 Zoning Resolution, which restricted the height that the street-side exterior walls of New York City buildings could rise before they needed to incorporate setbacks that recessed the buildings' exterior walls away from the streets.[118][a] Although the RCA Building was recessed so far into the block that it could have simply risen as a slab without any setbacks, Hood decided to include setbacks anyway because they represented "a sense of future, a sense of energy, a sense of purpose", according to the architecture expert Alan Balfour.[121] A subsequent change to the resolution in 1931, shortly after the Empire State Building opened, increased the maximum speed of New York City buildings' elevators from 700 feet per minute (210 m/min) to 1,200 feet per minute (370 m/min),[122] ostensibly due to lobbying from the Rockefeller family.[123] This allowed Rockefeller Center's designers to reduce the number of elevators in the complex's buildings, especially the RCA Building, since the skyscraper's proposed elevators would move faster.[124] Originally, the elevators were supposed to be installed by Otis Elevator Company, but Westinghouse Electric Corporation got the contract after moving into the RCA Building; this turned out to be a financially sound decision for Rockefeller Center since Westinghouse's elevators functioned better than Otis's.[125][126]

Hood and Corbett suggested some plans that were eccentric by contemporary standards. One plan entailed the construction of a massive pyramid spanning all three blocks; this was later downsized to a small retail pyramid, which evolved into the oval retail building.[40][127] Another plan included a system of vehicular ramps and bridges across the complex.[127] In July 1930, Hood and Corbett had briefly discussed the possibility of constructing the entire complex as a superblock with promenades leading from the RCA Building. This suggestion was not considered further because, as with the diagonal-streets plan, it would have involved decommissioning streets.[115] Eventually, all of the plans were streamlined into a more traditional design, with narrow rectangular slabs on all of the blocks set back from the street. Hood created a guideline that all of the office space in the complex would be no more than 27 feet (8.2 m) from a window, which was the maximum distance that sunlight could permeate the windows of a building at New York City's latitude.[128][129]

Plan F-18

Through the winter of 1930–1931, the plans were revised and streamlined.[130] The design of the complex became closer to the current one with the March 1931 announcement of Plan F-18.[117] The plan called for the International Music Hall (now Radio City Music Hall[131]) and its 31-story office building annex to occupy the northernmost of the three blocks, located between 50th and 51st Streets. The 66-story, 831-foot (253 m) RCA Building would be located on the central block's western half between 49th and 50th Streets, housing RCA and NBC offices as well as broadcasting studios. The oval-shaped retail complex would occupy the block's eastern half, with a rooftop garden. A RKO-operated sound theater would be located in the southernmost block between 48th and 49th Streets.[132] In the center of Radio City, running between Fifth and Sixth Avenues, would be a new three-block-long private street between Fifth and Sixth Avenues, with a concave plaza in the center of the block. The complex would also include space for a future Metropolitan Opera venue on the northernmost block.[132][133][134][130] For the first time, the plans included an underground pedestrian mall with shops, which would be located above the bus terminal.[117] The project was to cost $250 million,[135][136][48] and the complex would include 28,000 windows and more than 125,000 short tons (112,000 long tons) of structural steel, according to the builders.[132]

For the first time, a scale rendering of the proposed complex was presented to the public. The rendering was much criticized, with some pointing out the details or general dimensions of the as-yet-unconfirmed proposal, and others lambasting the location of the tall skyscrapers around the plaza.[137][138] Daniel Okrent writes that "almost everyone" hated the updated plans, and that renowned architectural scholar Lewis Mumford went into exile in upstate New York specifically because the "weakly conceived, reckless, romantic chaos" of the plans for Rockefeller Center had violated his sense of style. Mumford's commentary provoked a wave of blunt, negative criticism from private citizens; newspapers, such as the New York Herald Tribune; and architects, including Frank Lloyd Wright and Ralph Adams Cram, whose styles were diametrically opposed.[139] The New York Times took note of the "universal condemnation" of the proposal,[138] and after the architects changed their plans in response to the criticism, the Times stated, "It is cheering to learn that the architects and builders of Radio City have been stirred by the public criticism of their plans."[140] Despite the controversy over the complex's design, Rockefeller retained the Associated Architects for his project.[141]

Updated retail building and garden plans

The oval-shaped retail building on Fifth Avenue between 49th and 50th Streets was criticized for not fitting in with the rest of Fifth Avenue's architecture, with critics referring to the proposed building as an "oilcan".[138][142][143] The original plan had been for two retail buildings, but the oval building had been added as per Chase National bank's request for a single building.[130] It was scrapped in early 1931 after Chase could not win the exclusive rights to the building's banking location.[142][143] The updated plan F-19 restored two smaller 6-story retail buildings to the site of the oval building, as well as proposed a new 40-story tower on a nearby site. These buildings would not only provide the retail space but also fit in with Fifth Avenue's architecture.[142][144]

In the new plan, an oval-shaped central plaza would be recessed below ground level, with plantings surrounding a large central fountain. A wide planted esplanade between 50th and 51st Streets would lead pedestrians from Fifth Avenue in the east to the plaza and RCA Building on the west, with steps leading down to the plaza. The western side of the plaza would lead directly to the underground pedestrian mall.[145][146][147] A replica of Niagara Falls' Horseshoe Falls would also be built above a 100-by-20-foot (30.5 by 6.1 m) reflecting pool, while ivy would be planted on the outsides of some of the buildings.[147] In a June 1932 revision to the blueprint, the proposed plaza's shape was changed to a rectangle and the fountain was moved to the western side of the plaza.[148][149][150] The sculptor Paul Manship was then hired to create a sculpture on top of the fountain; his bronze Prometheus statue was installed on the site in 1934.[149][151]

As a concession for the loss of the rooftop gardens planned for the oval building, Hood suggested that all of the complex's setbacks below the 16th floor be covered with gardens.[147][152][150][153] Hood thought this was the cheapest way to make the buildings look attractive, with a cost estimate of $250,000 to $500,000 (about 3,630,000 to 7,261,000 in 2023[3]) that could pay for itself if the gardens were made into botanical gardens.[154][150] Hood proposed a three-tiered arrangement inspired by a similar plan from Le Corbusier. The lowest tier would be the ground level; the middle tier would comprise the retail buildings' low-lying roofs and the skyscrapers' setbacks; and the highest tier would consist of the tops of the skyscrapers.[155] A March 1932 update to the rooftop garden proposal also included two ornately decorated bridges that would connect the complex's three blocks,[156][150][157][158] though the bridge plan was later dismissed due to its high cost.[159] Ultimately, only seven disconnected gardens would be built.[160]

Since American tenants were reluctant to rent in the retail buildings, Rockefeller Center's manager Hugh Robertson, formerly of Todd, Robertson and Todd, suggested foreign tenants for the buildings.[161][162][163][164] They held talks with prospective Czech, German, Italian, and Swedish lessees who could potentially occupy the internationally-themed buildings on Fifth Avenue, although it was reported that Dutch, Chinese, Japanese, and Russian tenancies were also considered.[144][161][163] The first themed building that was agreed on was the British Empire Building, the more southerly of the two buildings, which would host the governmental and commercial ventures of the United Kingdom.[143][165] In February 1932, French tenants agreed to occupy the British Empire Building's twin to the north, La Maison Française.[166] A department store and 30-story building (later changed to 45 stories) was planned for the block to the north of the twin buildings, between 50th and 51st Streets, with the department store portion facing Fifth Avenue.[167][168] A "final" layout change to that block occurred in June, when the department store was replaced with the tower's two retail wings, which would be nearly identical to the twin retail buildings to their south. The two new retail buildings, connected to each other and to the main tower with a galleria, were proposed to serve Italian and possibly also German interests upon completion.[169][170]

Theaters

Out of the four theaters included in plan H-1 of March 1930, the city only approved the construction of two theaters,[102] and thus, only these two theaters were constructed.[111][130] Samuel Roxy Rothafel, a successful theater operator who was renowned for his domination of the city's theater industry,[171] joined the center's advisory board in 1930.[149][172][173] He offered to build two theaters: a large vaudeville "International Music Hall" on the northernmost block with more than 6,200 seats, and the smaller 3,500-seat "RKO Roxy" movie theater on the southernmost block.[173][174] The idea for these theaters was inspired by Roxy's failed expansion of the 5,920-seat Roxy Theatre on 50th Street, one and a half blocks away.[175][176][177] Roxy also envisioned an elevated promenade between the two theaters,[178] but this was never published in any of the official blueprints.[173] Meanwhile, proposals for a Metropolitan Opera House on the site persisted.[172] Official plans for a facility to the east of the RKO Roxy were filed in April 1932,[163] with the projected $250 million, 4,042-seat facility containing features such as a second-floor esplanade extending across 50th Street.[179] However, the opera had few finances on hand to fund such a move, so the proposed new opera house was relegated to a tentative status.[172]

In September 1931, a group of NBC managers and architects went to tour Europe to find performers and look at theater designs.[180][174][181][182] However, the group did not find any significant architectural details that they could use in the Radio City theaters.[183] In any case, Roxy's friend Peter B. Clark turned out to have much more innovative designs for the proposed theaters than the Europeans did.[184] The Music Hall was designed by architect Edward Durell Stone[185][186] and interior designer Donald Deskey[187][188] in the Art Deco style.[189] On the other hand, Eugene Schoen was selected to design the RKO Roxy.[190]

Pedestrian mall

In December 1931, the Rockefeller Center Corporation put forth its expanded plans for the underground pedestrian mall. It would now include a series of people mover tunnels, similar to the U.S. Capitol subway, which would link the complex to locations such as the Grand Central Terminal and Penn Station.[191] A smaller, scaled-down version of the plan was submitted to the New York City Board of Estimate in October 1933. They included two vehicular tunnels to carry 49th and 50th Streets underneath the entire complex, as well as a subterranean pedestrian mall connecting the buildings in the complex (see Rockefeller Center § Underground concourse). The plans included a 0.75-mile (1.21 km) system of pedestrian passages located 34 feet (10 m) underground, as well as a 125-by-96-foot (38 by 29 m) sunken lower plaza that connected to the mall via a wide concourse under the RCA Building.[192] The full-complex vehicular tunnels were not built; instead, a truck ramp from ground level to the underground delivery rooms was built at 50th Street.[193][194]

Unbuilt Metropolitan Avenue

An unfulfilled revision to the plan was submitted in May 1931, when Benjamin Wistar Morris, the architect of the original Opera proposal, advanced the extension of the complex's private passageway into a public "Metropolitan Avenue", which would run from 42nd to 59th Streets.[154] This avenue was planned so it would break up the 920-foot-long (280 m) distance between Fifth and Sixth Avenues, the longest distance between two avenues in Manhattan.[195] This was not a new proposal, as Mayor William Jay Gaynor had posited a similar avenue from 34th to 59th Streets in 1910,[196] and Wistar himself had proposed the avenue in 1929.[154] However, as it would involve the demolition of hundreds of buildings, this proposal was never acted on.[197]

Art program

Both Raymond Hood and John Todd believed that the center needed visual enhancement besides the rooftop gardens.[153] Initially, Todd had only planned to allocate about $150,000 toward the building's art program, but Junior wanted artworks that had meaningful purposes rather than purely aesthetic ones.[198] In November 1931, Todd suggested the creation of a program for placing distinctive artworks within each of the buildings.[199][200] Hartley Burr Alexander, a noted mythology and symbology professor, was tasked with planning the complex's arts installations.[201][199][202][203] Alexander submitted his plan for the site's artwork in December 1932. As part of the proposal, the complex would have a variety of sculptures, statues, murals, friezes, decorative fountains, and mosaics.[201] In an expansion of Hood's setback-garden plan, Alexander's proposal also included rooftop gardens atop all the buildings,[201] which would create a "Babylonian garden" when viewed from above.[135][152]

At first, Alexander suggested "Homo Fabor, Man the Builder" as the complex's overarching theme, representing satisfaction with one's occupation rather than with the wage.[202][204] However, that theme was not particularly well-received by the architects, so Alexander proposed another theme, the "New Frontiers;" this theme dealt with social and scientific innovations and represented the challenges that humanity faced "after the conquest of the physical world."[200] In theory, this was considered a fitting theme, but Alexander had been so specific about the details of the necessary artworks that it limited the creative license for any artists who would commission such works.[202] He had created a 32-page paper that explained exactly what needed to be done for each artwork, with some of the key themes underlined in all caps, that gave the paper "a tone more Martian than human" according to Okrent.[205] In March 1932, he was fired and replaced with a panel of five artists.[206][207] The panel agreed on the current theme, "The March of Civilization," but by that point some of the art of previous themes had already been commissioned, including the works that Alexander had proposed.[204][208]

The process of commissioning art for Rockefeller Center was complicated. Each building's architects would suggest some artwork. Todd would eliminate all of the unconventional proposals, and Rockefeller had the final say on many of the works.[209] There were many locations that needed art commissions, which prevented any specific artistic style from dominating the complex.[210] Specialists from around the world were retained for the art program: for instance, Edward Trumbull coordinated the colors of the works located inside the buildings, and Léon-Victor Solon did the same job for the exterior pieces.[211][203]

Gaston Lachaise, a renowned painter of female nudes, commissioned six uncontroversial bas-reliefs for Rockefeller Center, four at the front of the RCA Building West and two on the back of the International Building.[210][212] The Prometheus, Youth, and Maiden sculptures that Paul Manship commissioned for the complex were more prominently situated in the complex's Lower Plaza.[213] Barry Faulkner only had one commission for the entirety of Rockefeller Center: a mosaic mural located above the entrance of 1230 Avenue of the Americas.[214][215] Alfred Janniot also created a single work for Rockefeller Center, the bronze panel outside La Maison Francaise's entrance.[216][217] Lee Lawrie was by far the complex's most prolific artist, with 12 works;[218] most of his commissions were limestone screens above the main entrances of buildings, but he also had two of Rockefeller Center's best-known artworks: the Atlas statue in the International Building's courtyard, and the 37-foot-tall (11 m) Wisdom screen above the RCA Building's main entrance.[218][219] Ezra Winter, who created the "Quest for the Fountains of Eternal Youth" mural in Radio City Music Hall's lobby, largely adhered to Alexander's original specifications for the mural.[220][221]

One of the center's more controversial works was created by Diego Rivera, whom Nelson Rockefeller had hired to create a color fresco for the 1,071-square-foot (99 m2) wall in the RCA Building's lobby.[222][223] His painting, Man at the Crossroads, became controversial, as it contained Moscow May Day scenes and a clear portrait of Lenin, which had not been apparent in initial sketches (see Rockefeller Center § Man at the Crossroads.)[224][225] Nelson issued a written warning to Rivera to replace the offending figure with an anonymous face, but Rivera refused,[224][226] so in mid-1933, Rivera was paid for his commission and workers covered the mural with paper.[227] The fresco was demolished completely in February 1934[228] and it was subsequently replaced by Josep Maria Sert's American Progress mural.[229] As a result of the Man at the Crossroads controversy, Nelson scaled back his involvement with the complex's art, and his father began scrutinizing all of the following artworks commissioned for the center.[230]

One of the sculptor Attilio Piccirilli's works at Rockefeller Center would also be contested, albeit not until after the complex was finished.[231] He had created bas-relief carvings above the entrances of Palazzo d'Italia[232][233][234] and the International Building North.[232][234] Piccirilli's relief on the Palazzo d'Italia was removed in 1941 because the panels were seen as an overt celebration of fascism,[235][236][237] but his International Building North panels were allowed to remain.[231][238]

Change in name

During early planning, the development was often referred to as "Radio City".[40] Before the announcement that the development would include a mass media complex, there were also other appellations such as "Rockefeller City" and "Metropolitan Square" (after the Metropolitan Square Corporation).[239] Ivy Lee suggested changing the name to "Rockefeller Center". John Rockefeller Jr. initially did not want the Rockefeller family name associated with the commercial project, but was persuaded on the grounds that the name would attract far more tenants.[240] The name was formally changed in December 1931.[239] Rockefeller Jr. and The New York Times originally spelled the complex as "Rockefeller Centre", which was the British way of spelling "Center". After a consultation from the famed lexicographer Frank H. Vizetelly, "Centre" was changed to "Center".[241] Over time, the appellation of "Radio City" devolved from describing the entire complex to just the complex's western section,[62] and by 1937, only the Radio City Music Hall contained the "Radio City" name.[242]

Construction progress

According to Daniel Okrent, most sources estimated that between 40,000 and 60,000 people were hired during construction. One estimate by Raymond Fosdick, the Rockefeller Foundation head, placed the figure at 225,000 people, including workers who created materials for the complex elsewhere.[243] When construction started, the city was feeling the full effects of the Depression, with over 750,000 people unemployed and 64% of all construction workers without a job.[244] At the Depression's peak in the mid-1930s, John Rockefeller Jr. was praised as a job creator and a "patriot" for jump-starting the city's economy with the construction project.[245] Rockefeller made an effort to form amicable relationships with Rockefeller Center's workers.[246] Even when Rockefeller had to reduce wages for his union workers, he was praised for not reducing wages as severely as did other construction firms, many of which were either struggling or going bankrupt.[245] The complex was the largest private building project ever undertaken in contemporary times.[247] Carol Herselle Krinsky, in her 1978 book, describes the center as "the only large private permanent construction project planned and executed between the start of the Depression and the end of the Second World War".[248]

Land acquisition and clearing

For the project, 228 buildings on the site were razed and some 4,000 tenants relocated,[46][249] with the aggregate worth of the properties exceeding $7 billion.[133][249] (equivalent to $101,650,000,000 in 2023[3]) Rockefeller achieved this by buying expired or existing leases from the tenants.[249] In January 1929, William A. White & Sons was hired to conduct the eviction proceedings. They worked with the law firm Murray, Aldrich & Webb to give checks to tenants in exchange for property, sometimes for over $1 million.[250] The area was mostly occupied by illegal speakeasy bars, as the Prohibition Era had banned all sales of legal alcoholic beverages. Although the more tenuous of these speakeasies quickly moved elsewhere at the mere mention of formal eviction proceedings, other tenants, including some of the brothels, were harder to evict.[251] Many tenants only moved on certain conditions, and in one case, the firms acquired a lease from the estate of the late gambler Arnold Rothstein, who was murdered two months before he was set to be forcefully evicted from his Upper Estate property in January 1929.[252] Demolition of the structures started in spring 1930,[62] and all of the buildings' leases had been bought by August 1931.[253]

The center's managers then set to acquire the remaining properties along Sixth Avenue and at the southeast corner of the site so that they could create a larger complex, which led to the formation of the Underel Corporation. The negotiations of the Sixth Avenue Properties were conducted by different brokers and law firms so as to conceal the Rockefeller family's involvement in the Underel Corporation's acquisitions. However, there were several tenants along Sixth Avenue who initially refused to give up their properties.[254] Ella Wendel, the only survivor of a prominent real-estate family, did not give up her row house at 51st Street until her death in 1935.[255][256] Finally, 20th Century Fox founder and movie producer William Fox refused to sell his six row houses on 48th Street until late 1931, when the Center Theatre surrounding his property was almost complete.[257] Fox's properties would remain until the late 1930s, after much of the complex had been constructed.[258] In total, Charles Heydt spent $10 million ($145,214,000 in 2023 dollars[3]) on acquisition of the Sixth Avenue properties, as compared to the $6 million ($8,713,000 in 2023 dollars[3]) budgeted for the task.[257]

The tenants of two properties were allowed to stay: one lessee never received a sale offer due to a misunderstanding, and the other property's owners offered an exorbitant sale price for their property.[254] The grocer John F. Maxwell would only sell his property at 50th Street if he received $1 million in return. Owing to miscommunication, Heydt told Rockefeller that Maxwell would never sell, and Maxwell himself said that he had never been approached by the Rockefellers; consequently, Maxwell kept his property and Rockefeller Center did not purchase Maxwell's lease until 1970.[259][260] Maxwell's demand paled to that of Daniel Hurley and Patrick Daly, owners of a speakeasy at 49th Street, who would sell for $250 million. Rockefeller refused to pay, since it was around the cost of the entire property. They ended up leasing their property until 1975, and 30 Rockefeller Plaza was built around Maxwell's and Hurley and Daly's properties.[260][261]

On the southeast corner of the site, several property owners also refused to sell. Columbia University was willing to give Rockefeller Center Inc. control of all leases in the former Upper Estate that were no longer held by a third party. However, William Nelson Cromwell, a prominent lawyer and Columbia alumnus who owned three adjacent row houses at 10–14 West 49th Street, refused to move out of his property when his lease expired in 1927.[255][262] While he hired Nathan L. Miller, the former New York governor, to defend his property, Rockefeller's lawyers also planned to sue Columbia for not buying the property, since it represented a loss of income.[263] Robert Goelet planned to develop his lot at neighboring 2–6 West 49th, but could not do so because Cromwell controlled a property easement over part of Goelet's land.[264] Cromwell refused to pay rent on 14 West 49th Street until 1936, by which time Rockefeller Center Inc. had refused to hand over almost $400,000 of Cromwell's rent payments to Columbia. In 1936, he paid ten years of advance rent on 12 West 49th, counterbalancing the unpaid rent forne the neighboring row house, and agreed to forfeit 14 West 19th.[265] Rockefeller Center Inc. would later buy 8 West 49th, thus boxing Cromwell's land in between the two Rockefeller Center properties.[266]

Robert Goelet planned to develop his lot at neighboring 2–6 West 49th. Rockefeller Center Inc. considered Goelet's "interest and concern" to be a "large concern", and he was allowed to stay on the lot. However, he could not develop the land because Cromwell controlled a property easement over part of Goelet's land.[264] The St. Nicholas Church, on 48th Street behind Goelet's land, also refused to sell the property despite an offer of up to $7 million for the property.[267]

Late 1931: start of construction

Excavation of the Sixth Avenue side of the plot began in late July 1931,[268] commencing a seven-year period of excavation during which 556,000 cubic yards (425,000 m3) of schist would be removed from the site.[269] By fall, the empty blocks were pits up to 80-foot-deep (24 m), with a few buildings still standing at the edges of each block. 49th and 50th Streets resembled "causeways skimming the surface of a lake".[245] A field office for the project was erected on Fifth Avenue. It served as the headquarters for main construction contractors Todd & Brown, composed of John Todd's son Webster as well as Joseph O. Brown.[270] Brown was especially involved in reducing unnecessary costs from the project and selecting firms for supplies.[271]

Designs for the International Music Hall and RCA Building were submitted to the New York City Department of Buildings in August 1931, by which time the both buildings were to open in 1932.[272] Ultimately, the project's managers would submit 1,860 contracts to the Department of Buildings.[273] The contracts for the music hall and 66-story skyscraper were awarded two months later.[133] Rockefeller Center's construction progressed quickly, and in September 1931, construction began on the International Music Hall.[274] By October 1931, sixty percent of the digging was complete and the first contracts for the buildings had been let.[133] The foundations had been dug up to 50 feet (15 m) below ground, with each of the area's eighty-six piers descending up to 86 feet (26 m). Of the brownstones on site, 177 had been demolished by that October, with the majority of the remaining buildings located near the avenues.[133] Work on the new Roxy Theatre, to the south of the RCA Building, started that November.[177] The new Roxy Theatre was located to the south of the RCA Building, while the Music Hall was located to the north.[111]

The architects wished for a uniform facade color for all of the 14 new buildings.[136] To fulfill that end, Raymond Hood awarded a contract in December 1931 for the Indiana Limestone that would make up the fourteen buildings' facades. At the time, it was the largest order of stone in history, with about 14 million cubic feet (0.40×106 m3) of limestone being shipped.[275] Rockefeller Center's managers also ordered 154,000 short tons (138,000 long tons) of structural steel, the largest such order in history, making up an eighth of the projected $250 million construction cost. The steel order involved a bidding war between Bethlehem Steel and U.S. Steel; the order ultimately went to U.S. Steel, providing 8,000 jobs and a resultant net loss in profit.[276][277] Rockefeller Center also included nearly 23 acres (1 million square feet, 0.093×106 m2), of glass for its windows; 25,000 doors; and 50 thousand cubic feet (1.4×103 m3) of granite.[277]

As a result of the Depression, building costs were cheaper than projected. Although Metropolitan Life's loan of $126 million remained the same, the final cost of the first ten buildings came to $102 million ($1,784,000,000 in 2023 dollars[3]) by the time these structures were completed in 1935. John Todd used the surplus to install extra features into the buildings in case these features needed to be upgraded or repurposed. This resulted in expenditures such as wider-than-normal utility pipes, a subterranean boiler for the complex in case the steam system malfunctioned, and the complex's limestone facades.[278] Todd even installed sprinklers on the exteriors of the Fifth Avenue retail buildings in case they needed to be converted into factories, since sprinklers were required on industrial buildings at the time.[279] However, not all of the effects were positive: the construction boom of the late 1920s and early 1930s had almost doubled the total amount of real estate in Manhattan, and the construction of Rockefeller Center and the Empire State Building would increase the amount of space by another 56%. As a result, there was a lot of undervalued, vacant space. After RKO's bankruptcy in 1931, Sarnoff convinced John Rockefeller Jr. to buy RKO common stocks and RCA preferred stocks worth a total of $4 million ($69,969,000 in 2023 dollars[3]), in return for RCA downsizing its lease by 500 thousand square feet (46×103 m2).[280]

1932–1933

Work on the steel structure of the RCA Building started in March 1932.[281] Meanwhile, the British and French governments had already agreed to occupy the first two internationally-themed buildings, and John Rockefeller Jr. started signing tenants from the respective countries.[282] The cornerstone of the British Empire Building was laid in June, when Francis Hopwood, 1st Baron Southborough, placed the symbolic first stone in a ceremony.[283][284] Significant progress on the theaters had been made by then: the RKO Roxy's brickwork was complete and the limestone-and-granite facade was almost ready to be installed, while the Music Hall's steelwork was complete.[190] By September, both theaters were almost finished, as was the RCA Building, whose structural steel was up to the 64th floor.[285] That month also saw the opening of the RKO Building, the first structure in the complex to be opened.[286] The British Empire Building's structural steel started construction in October.[287]

The Music Hall was the second site to open, on December 27, 1932,[288][289][290] although it had topped out in August.[291] This was followed by the RKO Roxy's opening two days later.[292][293] Roxy originally intended to use the Music Hall as a vaudeville theater,[294][295] but the opening of the Music Hall was widely regarded as a flop,[292][296] and both theaters ended up being used for films and performing arts.[294][295][297] Radio City's Roxy Theatre had to be renamed the Center Theatre in May 1933 after a lawsuit by William Fox, who owned the original theater on 50th Street.[298] The failure of the vaudeville theater ended up ruining Roxy's enterprise, and he was forced to resign from the center's management in January 1934.[299][297][300]

The cornerstone of La Maison Francaise was laid on April 29, 1933, by former French prime minister Édouard Herriot.[301] The British Empire Building was open less than a week later.[302] The RCA Building was slated to be open by May 1,[303] but was delayed because of controversy over the Man at the Crossroads mural in the lobby.[304] In July 1933, the managers opened a 70th-story observation deck atop the RCA Building,[305] It was a great success: the 40-cents-per-head observation deck saw 1,300 daily visitors by late 1935.[306]

Work on the rooftop gardens started in October 1933,[307] and La Maison Francaise opened the same month.[308] In December 1933, workers erected the complex's famed Christmas tree in the center of the plaza for the first time.[309] Since then, it has been a tradition to display a large Christmas tree at the plaza between November and January of each year.[310]

Simultaneously, the city built the part of the canceled "Metropolitan Avenue" that ran through Rockefeller Center. The new street, called "Rockefeller Plaza", was projected to carry an estimated 7,000 vehicles per day upon opening.[311] The first segment between 49th and 50th Streets opened in 1933,[312] while a northern extension opened in 1934.[311] The new street measured over 60 feet (18 m) wide and ran 722 feet (220 m) through the complex, with four vehicular levels.[312]

Advertising and leasing efforts

From 1931 until 1944, Rockefeller Center Inc. employed Merle Crowell, the former editor of American Magazine, as the complex's publicist.[313] His first press release, published on July 25, 1931, extolled Rockefeller Center as "the largest building project ever undertaken by private capital". Thereafter, Crowell supplanted Ivy Lee as the complex's official publicity manager, and his subsequent releases employed a variety of superlatives, massive statistics and calculations, and the occasional hyperbole.[314] Crowell published many new press releases every day, and by the midpoint of the complex's construction in 1935, he also started staging celebrity appearances, news stories, and exhibitions at Rockefeller Center.[315] The goal was for 34,500 people to work at Rockefeller Center once it was completed, as well as 180,700 daily visitors.[316]

Rockefeller hired Hugh Sterling Robertson to solicit tenants and secure lease agreements.[317] It was hard to lease the complex in the wake of the Great Depression, but Robertson managed to identify 1,700 potential tenants, holding meetings with 1,200 of these entities by the end of 1933.[306] Rockefeller and his partners were also able to entice some prominent tenants to the center.[318] The Rockefeller family's Standard Oil Company moved into the RCA Building in 1934.[319] Over the next two years, several other major oil companies followed suit and took up leases in Midtown buildings,[320] including Sinclair Oil and Royal Dutch Shell, who moved into Rockefeller Center.[96] The United States Postal Service opened a post office location in the complex in early 1934, and would later rent space in the as-yet-incomplete International Building. The New York Museum of Science and Industry leased some of the unpopular space on the RCA Building's lower floors after Nelson Rockefeller became a trustee of the museum in fall 1935.[321] Westinghouse moved into the 14th through 17th floors of the RCA Building.[322]

However, Rockefeller Center's managers had a hard time leasing the buildings past 60% occupancy during the earliest years of its existence, which coincided with the middle of the Depression.[323] The Rockefeller family moved into various floors and suites throughout the same building in order to give potential tenants the impression of occupancy.[322] In particular, the family's office took up the entire 56th floor,[324] while the family's Rockefeller Foundation took up the entire floor below, and two other organizations supported by the Rockefellers also moved into the building.[325][324] Because the sunken central plaza was mostly leased by luxury stores, the complex's managers opened an outdoor restaurant in the plaza in early 1934 to attract other customers.[125] The complex's willingness to gain leases at almost any cost had repercussions of its own.[326] In January 1934, August Heckscher filed a $10,000,000 lawsuit against Rockefeller Center Inc. for convincing tenants to abandon their ongoing leases within his properties in order to take up cheaper leases at Rockefeller Center.[327] The lawsuit stalled in courts until Heckscher's death in 1941, when it was dismissed.[328][96]

The managers of Rockefeller Center Inc. also wanted the complex to have convenient, nearby mass transit to attract potential lessees.[329] The Independent Subway System (IND) had opened a subway station at Fifth Avenue and 53rd Street in 1933, which drew workers from Queens.[330][331] The managers, seeing the success of the business districts around Penn Station and Grand Central, proposed a large rail terminal for trains from Bergen County, New Jersey, so workers from northern New Jersey would be drawn to the complex. Although the managers did decide on a possible location for the terminal on 50th Street, this plan did not work because the IND subway still did not have any stops at the complex itself.[329] The consultants then offered a subway shuttle under 50th Street that would connect to the IND subway station at Eighth Avenue, or a rail line connecting to Penn Station and Grand Central. This plan also did not work because the city was uninterested in building the new rail line.[329] The plan was formally dropped in 1934, but proposals for similar ideas persisted until 1939. Since the IND was constructing their 47th–50th Streets station at the site, the Rockefeller Center's managers also wished to build their own connections to Penn Station and Grand Central using the subway tunnels under construction, a proposal that was also declined because it would require extensive rezoning of the surrounding residential area.[332] An extension of Rockefeller Plaza northward to the Rockefeller Apartments at 53rd Street was also envisioned in spring 1934, with the Rockefeller Center's managers acquiring land for the proposed street between October 1934 and late 1937.[333] Rockefeller legally condemned some of the buildings he acquired for the planned street expansion.[334] However, the street was never extended for various reasons.[333][b]

1934–1936

By July 1934, the complex had leased 80% of the available space in the six buildings that were already opened.[337][338] The lower plaza's large Prometheus statue had been installed in January of that year.[149][151] The complex's underground delivery ramps, located on 50th Street under the present-day Associated Press Building,[339] were installed in May.[193] The ramps, a vestige of the tunnels originally planned for 49th and 50th Streets, traveled 34 feet (10 m) underground and stretched for 450 feet (140 m).[193][194] By the end of the year, Wallace Harrison was the lead architect; Andrew Reinhard was in charge of floor plans for tenants; and Henry Hofmeister was tasked with planning the locations of the remaining unbuilt buildings' utilities and structural framework.[321][340] Raymond Hood had died, while Harvey Corbett had moved on to other projects, and the other three architects had little to do with Rockefeller Center's development in the first place.[340]

In May 1934, plans were officially filed for the remaining two International-themed buildings, as well as a larger 38-story, 512-foot (156 m) "International Building" at 45 Rockefeller Center. Work on the buildings started in September 1934.[341] The more southerly of the retail buildings was dubbed "Palazzo d'Italia" and was to serve Italian interests. The Italian government later reneged on its sponsorship of the building, and the task of finding tenants went to Italian-American businesses.[342][343][344] The more northerly small building was originally proposed for German occupation under the name "Deutsches Haus" before Adolf Hitler's rise to power in 1932.[342][345] Rockefeller had ruled the possibility out completely in September 1933 after being advised of Hitler's Nazi march toward totalitarianism.[62][163][346][347] Russia had also entered into negotiations to lease the final building in 1934,[341][348] but by 1935, the Russians were no longer actively seeking a lease.[349] With no definite tenant for the other building, the Rockefeller Center's managers reduced the proposed nine-story buildings to six stories,[342][350] enlarged and realigned the main building from a north-south to a west-east axis,[351][352] and replaced the proposed galleria between the two retail buildings with an expansion of the International Building's lobby.[343][342] The empty office site thus became "International Building North", rented by various international tenants.[350][353] In April 1935, developers opened the International Building and its two wings, which had been built in a record 136 days from groundbreaking to completion.[62][349][354][355] Aside from the averted controversy with the potential German tenants, the internationally-themed complex was seen as a symbol of solidarity during the interwar period, when Italy's entry in the League of Nations was obstructed by American isolationists.[356][357]

By late April 1935, the "Gardens of the Nations" on the RCA Building's 11th-story roof was complete.[358] Upon opening, the Garden of the Nations attracted many visitors because of its collection of exotic flora,[359] and it became the most popular garden in Rockefeller Center.[360] However, this novelty soon faded, and the gardens started running a $45,000-per-year deficit by 1937 ($787,000 in 2023 dollars[3]) due to the massive expense involved in hoisting plants, trees, and water to the roofs, as well as a lack of interest among tourists.[361] Gardens on the roofs of the two theaters would also be installed in 1937, but they were not open to the public.[362]

The underground pedestrian mall and ramp system, connecting the three blocks between 48th and 51st Streets, was finished in early May.[363] Twenty-two of the mall's 25 retail spaces were leased immediately,[337] and three more buildings were ready for occupancy that month.[363] The underground concourse contained a post office, payphones, and several public restrooms.[364] The complex was starting to attract large crowds of visitors, especially to Radio City Music Hall or one of the other exhibits and performance spaces in Rockefeller Center.[365] Despite this seeming success in the face of the Depression, construction was considered to be behind schedule: all the buildings had originally been set for completion by summer 1935, yet the central parts of the northern and southern blocks were still undeveloped.[337]

Around this time, the Rockefeller Center's managers were selling the land plots for their failed Rockefeller Plaza extension.[335][336] In January 1935, newly elected mayor Fiorello H. La Guardia proposed that a Municipal Art Center be built in or near the Rockefeller complex. It might have contained the Museum of Modern Art; the Guggenheim Collection; a costume museum; or broadcasting facilities for the Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS).[366] Initially, the project was supposed to be located in Central Park. However, due to legal challenges, the site for the planned art center was moved several blocks south to a site between 51st and 53rd Streets from Fifth to Sixth Avenues, immediately north of the Rockefeller Center.[367] In October 1936, the Museum of Modern Art acquired a site on 53rd Street, across the street from the Municipal Art Center site.[368] Several plans for an art center were discussed, but none were executed because of the same complications that befell the aborted Rockefeller Plaza extension.[369]

Also in 1935, plans were filed for a 16-story western extension of the RCA Building, made of the same material but with extensive links to the pedestrian tunnel system and an elaborate entrance from the under-construction IND station at 47th–50th Streets.[370] The subway connection started construction in 1936[364] but would not open until 1940.[35] Until the subway connection opened, the underground shopping mall was a elaborate catacomb that dead-ended on all sides.[364] The retail space on the lower plaza was not profitable because the stores in the plaza were hidden underneath the rest of the buildings and behind the Prometheus statue, which made the shops hard for tourists to find.[371][372] By 1935, there were ten times as many workers entering the RCA Building every day as there were visitors to the Lower Plaza.[372] After several rejected suggestions to beautify the plaza, the managers finally decided on building the Rink at Rockefeller Center for $2,000[372][373] after Nelson Rockefeller found that a new system had been invented that allowed artificial outdoor ice skating, enabling him to bring the pastime to Midtown Manhattan.[374] The new rink was open by Christmas 1936.[375][372][373] The rink was originally intended as a "temporary" measure,[374][373][376] but it became popular, and so the rink was kept.[376][377]

Completion

By 1936, ten buildings had been constructed and about 80% of the existing space had been rented.[194] The buildings, comprising the first phase of construction,[194] were the International Building; the four small retail buildings; the RKO Building; the Center Theatre; the Music Hall; the RCA Building; and the RCA Building's western extension.[378][194] The total investment in the center up to that point had been about $104.6 million[378][194] ($1,742,000,000 in 2023 dollars[3]), which was composed of $60 million of John Rockefeller Jr.'s money and $44.6 million from Metropolitan Life.[194]

Developing the remaining empty plots

Rockefeller Center Inc. needed to develop the remaining empty plots on the northern and southern blocks.[373] Notably, the southern plot was being used as a parking lot,[258] and at the time, it was the city's largest parking facility.[379] In 1936, Time Inc. expressed interest in moving out of their Chrysler Building offices into a larger headquarters, having just launched their Life magazine.[380] Rockefeller Center's managers persuaded Time to move to a proposed skyscraper on part of the southern empty lot, located on Rockefeller Plaza between 48th and 49th Streets.[373] The steelwork for that building was laid on September 25, 1936, and was complete by November 28, forty-three working days later.[381] The Time & Life Building, as it was known,[c] opened on April 1, 1937,[384][373] along with the final block of Rockefeller Plaza abutting the building, between 48th and 49th Streets.[384]

Rockefeller Center's executives went into talks with the Associated Press for a building on the northern empty lot,[385] which was occupied by the complex's truck delivery ramp.[194] The lot had been reserved for the Metropolitan Opera house, but the managers could not wait to develop the lot anymore, so in 1937, the opera plans were formally scrapped.[386][172] The lot had also been planned as a hotel site, but this was also deemed economically infeasible.[387] In January 1938, Associated Press agreed to rent four floors within the structure, with the building would be named for the company in exchange.[388] Construction of the steelwork started in April 1938, and after 29 working days, it was topped out by June.[389] The Associated Press moved into 50 Rockefeller Plaza in December.[390] The presence of Associated Press and Time Inc. expanded Rockefeller Center's scope from strictly a radio-communications complex to a hub of both radio and print media.[391] In 1938, the Associated Press opened the Guild, a newsreel theater,[391] along the curve of the truck ramp below the building.[392]

It was impossible to build any smaller buildings in the remainder of the complex, since the demands of contemporary tenants stipulated larger buildings.[393] Additionally, it was no longer viable to build a system of rooftop gardens because the 15-story Associated Press Building was much taller than the 7- to 11-story-high gardens on the rest of the buildings, making it impossible to create a system of gardens without the use of impossibly steep bridges.[160][352][385] The final plot on the southernmost block needed to be developed, and several tenants were being considered.[386] In spring 1937, the center's managers approached the Dutch government for a possible 16-story "Holland House" on the eastern part of the plot.[394][395] The Dutch government did not enter the agreement because of troubles domestically, most notably Hitler's invasion of the Netherlands.[379][396] However, the Rockefeller Center's managers were already in negotiations with Eastern Air Lines, whose CEO Eddie Rickenbacker would sign a lease in June 1940.[397][398] Excavation started in October 1938, and the building was topped out by April 1939.[399] Upon the Eastern Air Lines Building's completion, the Dutch government moved its offices-in-exile into the new building.[379]

Change in leadership

The management of Rockefeller Center shifted around this time.[400] In November 1936, John Todd was featured in two New Yorker articles that emphasized his role in the complex's construction.[401] At the same time, Nelson was gaining clout within Rockefeller Center Inc., and he often disagreed with nearly all of Todd's suggestions.[402] Nelson's father John was being phased out of the process of constructing Rockefeller Center, since the Rockefeller family's youngest son David had moved out of the family home at 10 West 54th Street.[403] By April 1937, Todd regretted his decision to be featured in The New Yorker.[404] In March 1938, Nelson became the president of Rockefeller Center Inc. He then fired Todd as the complex's manager and appointed Hugh Robertson in his place.[400][405] Nelson and Robertson wanted to avoid workers' strikes, which would delay the completion of construction. Nelson, Robertson, and the workers' unions agreed to a contract in which the unions would not strike, Robertson would not lock out union workers, and both would agree to arbitration if a labor dispute arose.[406] Rockefeller Center was one of Nelson's primary business ventures until 1958, when he became the Governor of New York.[407]

Public relations officials were hired to advertise the different parts of the complex, such as the gardens or the plaza.[408] Merle Crowell set up a viewing platform on the east side of Rockefeller Center and founded the facetious "Sidewalk Superintendents' Club" so the public could view construction.[403]

Final building

The western half of the southern plot was still undeveloped due to perceived negative effects from the Sixth Avenue elevated.[409][410] Ultimately, the United States Rubber Company was convinced to move from their headquarters at 1790 Broadway, in Columbus Circle, to the proposed 1230 Avenue of the Americas building at Rockefeller Center. The company leased eleven floors in the new building, a decrease of 35,000 square feet (3,300 m2) from the 12 stories that they leased at 1790 Broadway.[411] The U.S. Rubber Company Building had been planned as a mirror of the RKO Building, but this was not possible because the symmetrical structure would have entailed constructing an expensive cantilever over the Center Theatre.[400] Excavation of the U.S. Rubber Company Building site commenced in May 1939.[412]

The complex was deemed complete by the end of October 1939.[413] John Rockefeller Jr. installed the building's ceremonial final rivet on November 1, 1939, marking the completion of the original complex.[62][414][415] The installation of the last rivet was accompanied by a celebratory speech from Rockefeller and many news accounts about the event.[416] The Eastern Air Lines Building, meanwhile, was not officially complete until its dedication in October 1940.[417][397]

Later construction

After the original complex was finished, Rockefeller started to look for ways to expand, even though the outbreak of World War II stopped almost all civilian construction projects.[418] In 1943, the complex's managers bought land and buildings on three street corners near the complex.[419] Rockefeller Center unveiled plans for expansion to the southwest and north in 1944. At the time, the complex's existing rentable area totaled 5.29 million square feet (0.491×106 m2), with 99.7% of the space being leased.[420]

1940s and 1950s