Lysine

| |||

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Lysine

| |||

| Other names

2,6-Diaminohexanoic acid; 2,6-Diammoniohexanoic acid

| |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (JSmol)

|

|||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChEMBL | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.673 | ||

| KEGG | |||

PubChem CID

|

|||

| UNII | |||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| C6H14N2O2 | |||

| Molar mass | 146.190 g·mol−1 | ||

| 1.5 kg/L @ 25 °C | |||

| Pharmacology | |||

| B05XB03 (WHO) | |||

| Supplementary data page | |||

| Lysine (data page) | |||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |||

Lysine (symbol Lys or K),[1] encoded by the codons AAA and AAG, is an α-amino acid that is used in the biosynthesis of proteins. It contains an α-amino group (which is in the protonated −NH3+ form under biological conditions), an α-carboxylic acid group (which is in the deprotonated −COO− form under biological conditions), and a side chain lysyl ((CH2)4NH2), classifying it as a charged (at physiological pH), aliphatic amino acid. It is essential in humans, meaning the body cannot synthesize it and thus it must be obtained from the diet.

Lysine is a base, as are arginine and histidine. The ε-amino group often participates in hydrogen bonding and as a general base in catalysis. The ε-ammonium group (NH3+) is attached to the fourth carbon from the α-carbon, which is attached to the carboxyl (C=OOH) group.[2]

Common posttranslational modifications include methylation of the ε-amino group, giving methyl-, dimethyl-, and trimethyllysine (the latter occurring in calmodulin); also acetylation, sumoylation, ubiquitination, and hydroxylation – producing the hydroxylysine in collagen and other proteins. O-Glycosylation of hydroxylysine residues in the endoplasmic reticulum or Golgi apparatus is used to mark certain proteins for secretion from the cell. In opsins like rhodopsin and the visual opsins (encoded by the genes OPN1SW, OPN1MW, and OPN1LW), retinaldehyde forms a Schiff base with a conserved lysine residue, and interaction of light with the retinylidene group causes signal transduction in color vision (See visual cycle for details). Deficiencies may cause blindness, as well as many other problems due to its ubiquitous presence in proteins.

Lysine was first isolated by the German biological chemist Ferdinand Heinrich Edmund Drechsel (1843–1897) in 1889 from the protein casein in milk.[3] He named it "lysin".[4] In 1902, the German chemists Emil Fischer and Fritz Weigert determined lysine's chemical structure by synthesizing it.[5]

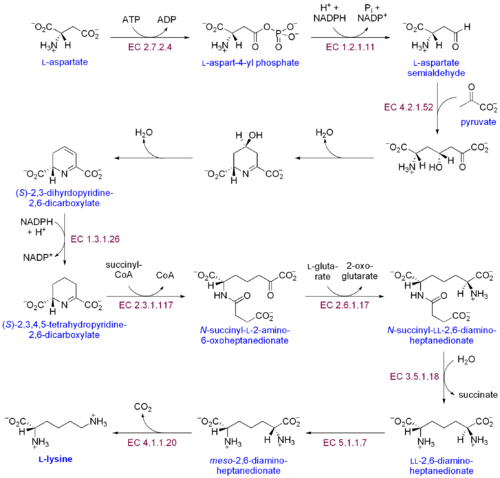

Biosynthesis

As an essential amino acid, lysine is not synthesized in animals, hence it must be ingested as lysine or lysine-containing proteins. In plants and most bacteria, it is synthesized from aspartic acid (aspartate):[6]

- L-aspartate is first converted to L-aspartyl-4-phosphate by aspartokinase (or aspartate kinase). ATP is needed as an energy source for this step.

- β-Aspartate semialdehyde dehydrogenase converts this into β-aspartyl-4-semialdehyde (or β-aspartate-4-semialdehyde). Energy from NADPH is used in this conversion.

- 4-hydroxy-tetrahydrodipicolinate synthase adds a pyruvate group to the β-aspartyl-4-semialdehyde, and a water molecule is removed. This causes cyclization and gives rise to (2S,4S)-4-hydroxy-2,3,4,5-tetrahydrodipicolinate.

- This product is reduced to 2,3,4,5-tetrahydrodipicolinate (or Δ1-piperidine-2,6-dicarboxylate, in the figure: (S)-2,3,4,5-tetrahydropyridine-2,6-dicarboxylate) by 4-hydroxy-tetrahydrodipicolinate reductase. This reaction consumes an NADPH molecule and releases a second water molecule.

- Tetrahydrodipicolinate N-acetyltransferase opens this ring and gives rise to N-succinyl-L-2-amino-6-oxoheptanedionate (or N-acyl-2-amino-6-oxopimelate). Two water molecules and one acyl-CoA (succinyl-CoA) enzyme are used in this reaction.

- N-succinyl-L-2-amino-6-oxoheptanedionate is converted into N-succinyl-LL-2,6-diaminoheptanedionate (N-acyl-2,6-diaminopimelate). This reaction is catalyzed by the enzyme succinyl diaminopimelate aminotransferase. A glutamic acid molecule is used in this reaction and an oxoacid is produced as a byproduct.

- N-succinyl-LL-2,6-diaminoheptanedionate (N-acyl-2,6-diaminopimelate)is converted into LL-2,6-diaminoheptanedionate (L,L-2,6-diaminopimelate) by succinyl diaminopimelate desuccinylase (acyldiaminopimelate deacylase). A water molecule is consumed in this reaction and a succinate is produced a byproduct.

- LL-2,6-diaminoheptanedionate is converted by diaminopimelate epimerase into meso-2,6-diamino-heptanedionate (meso-2,6-diaminopimelate).

- Finally, meso-2,6-diamino-heptanedionate is converted into L-lysine by diaminopimelate decarboxylase.

Enzymes involved in this biosynthesis include:[6]

- Aspartokinase

- Aspartate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase

- 4-hydroxy-tetrahydrodipicolinate synthase

- 4-hydroxy-tetrahydrodipicolinate reductase

- 2,3,4,5-tetrahydropyridine-2,6-dicarboxylate N-succinyltransferase

- Succinyldiaminopimelate transaminase

- Succinyl-diaminopimelate desuccinylase

- Diaminopimelate epimerase

- Diaminopimelate decarboxylase.

It is worth noting, however, that in fungi, euglenoids and some prokaryotes lysine is synthesized via the alpha-aminoadipate pathway.

Metabolism

Lysine is metabolised in mammals to give acetyl-CoA, via an initial transamination with α-ketoglutarate. The bacterial degradation of lysine yields cadaverine by decarboxylation.

Allysine is a derivative of lysine, used in the production of elastin and collagen. It is produced by the actions of the enzyme lysyl oxidase on lysine in the extracellular matrix and is essential in the crosslink formation that stabilizes collagen and elastin.

Requirements

The Food and Nutrition Board (FNB) of the U.S. Institute of Medicine set Recommended Dietary Allowances (RDAs) for essential amino acids in 2002. For lysine, for adults 19 years and older, 38 mg/kg body weight/day.[7]

Synthesis

Synthetic, racemic lysine has long been known.[8] A practical synthesis starts from caprolactam.[9] Industrially, L-lysine is usually manufactured by a fermentation process using Corynebacterium glutamicum; production exceeds 600,000 tons a year.[10]

L-lysine HCl is used as a dietary supplement, providing 80.03% L-lysine.[11] As such, 1 g of L-lysine is contained in 1.25 g of L-lysine HCl.

Dietary sources

The nutritional requirement per day, in milligrams of lysine per kilogram of body weight, is: infants (3–4 months) 103 mg/kg, children (2 years) 64 mg/kg, older children (10–12 years) 44 to 60 mg/kg, adults 12 mg/kg.[12] For a 70 kg adult, 12 milligrams of lysine per kilogram of body weight is 0.84 grams of lysine. Recommendations for adults have been revised upwards to 30 mg/kg.[13]

Good sources of lysine are high-protein foods such as eggs, meat (specifically red meat, lamb, pork, and poultry), soy, beans and peas, cheese (particularly Parmesan), and certain fish (such as cod and sardines).[14]

Lysine is the limiting amino acid (the essential amino acid found in the smallest quantity in the particular foodstuff) in most cereal grains, but is plentiful in most pulses (legumes).[15] A vegetarian or low animal protein diet can be adequate for protein, including lysine, if it includes both cereal grains and legumes, but there is no need for the two food groups to be consumed in the same meals.

A food is considered to have sufficient lysine if it has at least 51 mg of lysine per gram of protein (so that the protein is 5.1% lysine).[16] Foods containing significant proportions of lysine include:

| Food | Lysine (% of protein) |

|---|---|

| Fish | 9.19% |

| Beef, ground, 90% lean/10% fat, cooked | 8.31% |

| Chicken, roasting, meat and skin, cooked, roasted | 8.11% |

| Azuki bean (adzuki beans), mature seeds, raw | 7.53% |

| Milk, non-fat | 7.48% |

| Soybean, mature seeds, raw | 7.42% |

| Egg, whole, raw | 7.27% |

| Pea, split, mature seeds, raw | 7.22% |

| Lentil, pink, raw | 6.97% |

| Kidney bean, mature seeds, raw | 6.87% |

| Chickpea, (garbanzo beans, Bengal gram), mature seeds, raw | 6.69% |

| Navy bean, mature seeds, raw | 5.73% |

Properties

L-Lysine plays a major role in calcium absorption; building muscle protein; recovering from surgery or sports injuries; and the body's production of hormones, enzymes, and antibodies.

Modifications

Lysine can be modified through acetylation (acetyllysine), methylation (methyllysine), ubiquitination, sumoylation, neddylation, biotinylation, pupylation, and carboxylation, which tends to modify the function of the protein of which the modified lysine residue(s) are a part.[17]

Clinical significance

A review cited studies showing that lysine supplementation can decrease herpes simplex cold sore outbreaks and reduce healing time.[18] Original article published at 1978.[19]

However, at 1984 and later the controlled researches don't confirm this for humans and animals.[20][21]

An authoritative Cochrane Review published in 2015 concluded there is insufficient evidence that lysine supplementation is effective against herpes simplex virus; it has not been approved by the FDA for herpes simplex suppression.[22][23]

Use of lysine in animal feed

Lysine production for animal feed is a major global industry, reaching in 2009 almost 700,000 tonnes for a market value of over €1.22 billion.[24] Lysine is an important additive to animal feed because it is a limiting amino acid when optimizing the growth of certain animals such as pigs and chickens for the production of meat. Lysine supplementation allows for the use of lower-cost plant protein (maize, for instance, rather than soy) while maintaining high growth rates, and limiting the pollution from nitrogen excretion.[25] In turn, however, phosphate pollution is a major environmental cost when corn is used as feed for poultry and swine.[26]

Lysine is industrially produced by microbial fermentation, from a base mainly of sugar. Genetic engineering research is actively pursuing bacterial strains to improve the efficiency of production and allow lysine to be made from other substrates.[24]

In popular culture

The 1993 film Jurassic Park (based on the 1990 Michael Crichton novel of the same name) features dinosaurs that were genetically altered so that they could not produce lysine.[27] This was known as the "lysine contingency" and was supposed to prevent the cloned dinosaurs from surviving outside the park, forcing them to be dependent on lysine supplements provided by the park's veterinary staff. In reality, no animals are capable of producing lysine (it is an essential amino acid).[28]

Lysine is the favorite amino acid of the character Sheldon Cooper in the television show, The Big Bang Theory. It was mentioned in season 2, episode 13, "The Friendship Algorithm".[29]

In 1996, lysine became the focus of a price-fixing case, the largest in United States history. The Archer Daniels Midland Company paid a fine of US$100 million, and three of its executives were convicted and served prison time. Also found guilty in the price-fixing case were two Japanese firms (Ajinomoto, Kyowa Hakko) and a South Korean firm (Sewon).[30] Secret video recordings of the conspirators fixing lysine's price can be found online or by requesting the video from the U.S. Department of Justice, Antitrust Division. This case served as the basis of the movie The Informant!, and a book of the same title.[31]

The 2002 album Mastered by Guy at The Exchange by Max Tundra features a song called "Lysine".

See also

References

- ^ IUPAC-IUBMB Joint Commission on Biochemical Nomenclature. "Nomenclature and Symbolism for Amino Acids and Peptides". Recommendations on Organic & Biochemical Nomenclature, Symbols & Terminology etc. Retrieved 17 May 2007.

- ^ Lysine. The Biology Project, Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biophysics, University of Arizona.

- ^ Drechsel, E. (1889). "Zur Kenntniss der Spaltungsprodukte des Caseïns" [[Contribution] to [our] knowledge of the cleavage products of casein]. Journal für Praktische Chemie. 2nd series (in German). 39: 425–429. On p. 428, Drechsel presented an empirical formula for the chloroplatinate salt of lysine – C8H16N2O2Cl2•PtCl4 + H2O – but he later admitted that this formula was wrong because the salt's crystals contained ethanol instead of water. See: Drechsel, E. (1891) "Der Abbau der Eiweissstoffe" [The disassembly of proteins], Archiv für Anatomie und Physiologie, 248–278. §2. Drechsel, E. "Zur Kenntniss der Spaltungsproducte des Caseïns" ([Contribution] to [our] knowledge of the cleavage products of casein), pp. 254–260. From p. 256: " … die darin enthaltene Base hat die Formel C6H14N2O2. Der anfängliche Irrthum ist dadurch veranlasst worden, dass das Chloroplatinat nicht, wie angenommen ward, Krystallwasser, sondern Krystallalkohol enthält, … " ( … the base [that's] contained therein has the [empirical] formula C6H14N2O2. The initial error was caused by the chloroplatinate containing not water in the crystal (as was assumed), but ethanol … )

- ^ Drechsel, E. (1891) "Der Abbau der Eiweissstoffe" [The disassembly of proteins], Archiv für Anatomie und Physiologie, 248–278. §4. Fischer, Ernst (1891) "Ueber neue Spaltungsproducte des Leimes" (On new cleavage products of gelatin), pp. 465–469. From p. 469: " … die Base C6H14N2O2, welche mit dem Namen Lysin bezeichnet werden mag, … " ( … the base C6H14N2O2, which may be designated with the name "lysine", … ) [Note: Ernst Fischer was a graduate student of Drechsel.]

- ^ Fischer, Emil; Weigert, Fritz (1902). "Synthese der α,ε – Diaminocapronsäure (Inactives Lysin)" [Synthesis of α,ε-diaminohexanoic acid ([optically] inactive lysine)]. Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft (in German). 35: 3772–3778.

- ^ a b c "MetaCyc: L-lysine biosynthesis I".

- ^ Institute of Medicine (2002). "Protein and Amino Acids". Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrates, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein, and Amino Acids. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. pp. 589–768.

- ^ Braun, J. V. (1909). "Synthese des inaktiven Lysins aus Piperidin". Berichte der deutschen chemischen Gesellschaft. 42: 839–846. doi:10.1002/cber.190904201134.

- ^ Eck, J. C.; Marvel, C. S. (1943). "dl-Lysine Hydrochlorides" (PDF). Organic Syntheses, Collected. 2: 374. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2007.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Pfefferle, W.; Möckel, B.; Bathe, B.; Marx, A. (2003). "Biotechnological manufacture of lysine". Advances in Biochemical Engineering/Biotechnology. Advances in Biochemical Engineering/Biotechnology. 79: 59–112. doi:10.1007/3-540-45989-8_3. ISBN 978-3-540-43383-5. PMID 12523389.

- ^ "Dietary Supplement Database: Blend Information (DSBI)".

L-LYSINE HCL 10000820 80.03% lysine

- ^ United Nations Food; Agriculture Organization : Agriculture and Consumer Protection. "Energy and protein requirements: 5.6 Requirements for essential amino acids". Retrieved 10 October 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ FAO/WHO/UNU (2007). "PROTEIN AND AMINO ACID REQUIREMENTS IN HUMAN NUTRITION" (PDF). WHO Press., page 150-152

- ^ University of Maryland Medical Center. "Lysine". Retrieved 30 December 2009.

- ^ Young VR, Pellett PL (1994). "Plant proteins in relation to human protein and amino acid nutrition" (PDF). American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 59 (5 Suppl): 1203S–1212S. doi:10.1093/ajcn/59.5.1203s. PMID 8172124.

- ^ Institute of Medicine of the National Academies. "Dietary Reference Intakes for Macronutrients". p. 589. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- ^ Sadoul K, Boyault C, Pabion M, Khochbin S (February 2008). "Regulation of protein turnover by acetyltransferases and deacetylases". Biochimie. 90 (2): 306–12. doi:10.1016/j.biochi.2007.06.009. PMID 17681659.

- ^ Gaby AR (2006). "Natural remedies for Herpes simplex". Altern Med Rev. 11 (2): 93–101. PMID 16813459.

- ^ Griffith RS, Norins AL, Kagan C. (1978). "A multicentered study of lysine therapy in Herpes simplex infection". Dermatologica. 156 (5): 257–267. doi:10.1159/000250926. PMID 640102.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ John J. DiGiovanna, MD; Harvey Blank, MD (1984). "Failure of Lysine in Frequently Recurrent Herpes Simplex Infection: Treatment and Prophylaxis". Dermatology. 120 (1): 48–51. doi:10.1001/archderm.1984.01650370054010. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sebastiaan Bol, Evelien M Bunnik (2015). "Lysine supplementation is not effective for the prevention or treatment of feline herpesvirus 1 infection in cats: A systematic review". BMC Veterinary Research. 11 (1): 284. doi:10.1186/s12917-015-0594-3.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Ching-Chi Chi1, Shu-Hui Wang, Finola M Delamere, Fenella Wojnarowska, Mathilde C Peters, Preetha P Kanjirath (2015). "Interventions for prevention of herpes simplex labialis (cold sores on the lips)". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (8): CD010095. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010095.pub2. PMID 26252373. CD010095.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Drugs.com. "Herpes Simplex, Suppression Medications". Retrieved 19 May 2014.

- ^ a b "AllAboutFeed – News: Norwegian granted for improving lysine production process". archive.org. 11 March 2012. Retrieved 14 April 2018.

- ^ Toride Y. "Lysine and other amino acids for feed: production and contribution to protein utilization in animal feeding". Retrieved 25 January 2011.

- ^ Abelson, Philip (March 1999). "A Potential Phosphate Crisis". Science. 283 (5410): 2015. doi:10.1126/science.283.5410.2015. PMID 10206902.

- ^ Coyne, Jerry A. (10 October 1999). "The Truth Is Way Out There". The New York Times. Retrieved 6 April 2008.

- ^ Wu, G (2009). "Amino acids: Metabolism, functions, and nutrition". Amino Acids. 37 (1): 1–17. doi:10.1007/s00726-009-0269-0. PMID 19301095.

- ^ M3ta1 (28 February 2011). "Sheldon's Favourite Amino Acid". Retrieved 14 April 2018 – via YouTube.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Connor, J.M.; "Global Price Fixing" 2nd Ed. Springer-Verlag: Heidelberg, 2008. ISBN 978-3-540-78669-6.

- ^ Eichenwald, Kurt.; "The Informant: a true story" Broadway Books: New York, 2000. ISBN 0-7679-0326-9.

Sources

- Much of the information in this article has been translated from German Wikipedia.

- Lide, D. R., ed. (2002). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (83rd ed.). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. ISBN 0-8493-0483-0.