Dragnet (franchise)

Dragnet was a popular, influential and long-running radio and television police procedural about the cases of a dedicated Los Angeles police detective, Sergeant Joe Friday, and his partners. The show takes its name from an actual police term, a dragnet for any system of coordinated measures for apprehending criminals or suspects.

Introduction

Dragnet was perhaps the most famous and influential police procedural of all time. The series has been credited with dramatically improving the public image of the police in the United States[citation needed].

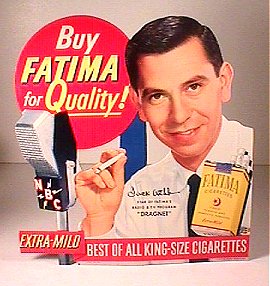

Actor and producer Jack Webb’s aims in Dragnet were for realism and unpretentious acting. He achieved both goals, and Dragnet remains a key influence on subsequent police dramas in many media.

The show's cultural impact is demonstrated by the fact that even after five decades, elements of Dragnet are known to those who've never seen or heard the program:

- The ominous, four-note introduction to the brass and tympani theme music (titled "Danger Ahead") is instantly recognizable (though its origins date back to Miklós Rózsa's score for the 1946 film version of The Killers).

- Another Dragnet trademark is the show's opening narration: "Ladies and gentlemen: the story you are about to hear is true. Only the names have been changed to protect the innocent." This underwent minor revisions over time. The "only" and "ladies and gentlemen" were dropped at some point, and for the television version "hear" was changed to "see". Variations on this narration have been featured in many subsequent crime dramas, and in satires of these dramas.

On radio, Dragnet ran from June 3, 1949 to February 26 1957. Dragnet appeared on television from December 16 1951 to 1959, and from 1967 to 1970 on Thursday nights. All of these versions ran on NBC.

History

Creation

Dragnet was created and produced by Jack Webb, who starred as the terse Sgt. Friday. Webb had starred in a few mostly short-lived radio programs, but Dragnet would make him one of the major media personalities of his era.

Dragnet had its origins in Webb’s small role as a police forensic scientist in the 1948 film, He Walked by Night, inspired by the actual murder of a police officer in Los Angeles. The film was depicted in semidocumentary style, and Marty Wynn (an LAPD sergeant) was a technical advisor on the film. Webb and Wynn became friends, and both thought that the day-to-day activities of police officers could be realistically depicted, and could make for compelling drama without the forced sense of melodrama then so common in radio programming (and very common on movies and television today). Webb frequently visited police headquarters, drove with police patrols, and attended police academy courses to learn authentic jargon and other details that could be featured in a radio program. When he proposed Dragnet to NBC officials, they were not especially impressed; radio was aswarm with private investigators and crime dramas, such as Webb’s earlier Pat Novak for Hire. That program didn’t last long, but Webb had received high marks for his role as the titular private investigator, and NBC agreed to a limited run for Dragnet.

With writer James E. Moser, Webb prepared an audition recording, then sought the LAPD’s endorsement; he wanted to use cases from official files in order to demonstrate the steps taken by police officers during investigations. The official response was initially lukewarm, but they offered Webb the endorsement he sought. Police wanted control over the program’s sponsor, and insisted that police not be depicted unflatteringly. This would lead to some criticism, as LAPD racial segregation policies were never addressed, nor was there a suggestion of police corruption.

Radio

Dragnet debuted inauspiciously. The first several months were bumpy, as Webb and company worked out the program’s format and eventually became comfortable with their characters (Friday was originally portrayed as more brash and forceful than his later usually relaxed demeanor). Gradually, Friday’s deadpan, fast-talking persona emerged, described by John Dunning as "a cop's cop, tough but not hard, conservative but caring." (Dunning, 210) Friday’s first partner was Sgt. Ben Romero, portrayed by Barton Yarborough, a longtime radio actor. When Dragnet hit its stride, it became one of radio’s top-rated shows.

Webb insisted on realism in every aspect of the show. The dialogue was clipped, understated and sparse, influenced by the hard boiled school of crime fiction. Scripts were fast moving but didn’t seem rushed. Every aspect of police work was chronicled, step by step: From patrols and paperwork, to crime scene investigation, lab work and questioning witnesses or suspects. The detectives’ personal lives were mentioned, but rarely took center stage. (Friday was a bachelor who lived with his mother; Romero was an ever-fretful husband and father) "Underplaying is still acting," Webb told Time. "We try to make it as real as a guy pouring a cup of coffee.” (Dunning, 209) Los Angeles police chiefs C.B. Horrall and (later) William H. Parker were credited as consultants, and many police officers were fans.

Webb was a stickler for accurate details, and Dragnet used many authentic touches, such as the LAPD's actual radio call sign (KMA-367), and the names of many real department officials, such as Ray Pinker and Lee Jones of the crime lab or Chief of Detectives Thad Brown.

Episodes began with an announcer describing the basic premise of the show. "Big Saint" (April 26, 1951) for example, begins with, "You're a Detective Sergeant, you're assigned to auto theft detail. A well organized ring of car thieves begins operations in your city. It's one of the most puzzling cases you've ever encountered. Your job: break it."

Friday offered voice-over narration throughout the episodes, noting the time, date and place of every scene as he and his partners went through their day investigating the crime. The events related in a given episode might occur in a few hours, or might span a few months. At least one episode unfolded in real time: in "City Hall Bombing" (July 21, 1949), Friday and Romero had less than 30 minutes to stop a man who was threatening to destroy the City Hall with a bomb.

At the end of the episode, the announcer would relate the fate of the suspect. They were usually convicted of a crime and sent to "the State Penitentiary, San Quentin" or a mental hospital, but other occasions the cases had ambiguous, unusual or even disappointing resolutions. Sometimes, criminals avoided justice or escaped, at least on the radio version of Dragnet. In 1950, Time quoted Webb: "We don’t even try to prove that crime doesn’t pay ... sometimes it does" (Dunning, 210)

Specialized terminology was mentioned in every episode, but was rarely explained. Webb trusted the audience to determine the meanings of words or terms by their context, and furthermore, Dragnet tried to avoid the kinds of awkward, lengthy exposition that people wouldn’t actually use in daily speech. Several specialized terms (such as "A.P.B." for "All Points Bulletin" and "M.O." for "Modus Operandi") were rarely used in popular culture before Dragnet introduced them to everyday America.

While most radio shows used one or two sound effects experts, Dragnet needed five; a script clocking in at just under 30 minutes could require up to 300 separate effects. Accuracy was underlined: The exact number of footsteps from one room to another at Los Angeles police headquarters were imitated, and when a telephone rang at Friday’s desk, the listener heard the same ring as the telephones in Los Angeles police headquarters. A single minute of "A Gun For Christmas" is a representative example of the evocative sound effects featured on "Dragnet". While Friday and others investigate bloodstains in a suburban backyard, the listener hears a series of overlapping effects: a squeaking gate hinge, footsteps, a technician scraping blood into a paper envelope, the glassy chime of chemical vials, bird calls and a dog barking in the distance.

Scripts tackled a number of topics, ranging from the thrilling (murders, missing persons and armed robbery) to the mundane (check fraud and shoplifting), yet "Dragnet" made them all interesting due to fast-moving plots and behind-the-scenes realism. In "The Garbage Chute" (15 December 1949), they even had a locked room mystery.

Template:Spoiler Though rather tame by modern standards, Dragnet--especially on the radio--handled controversial subjects such as sex crimes and drug addiction with unprecedented and even startling realism. Dragnet broke one of the unspoken (and still rarely broached) taboos of popular entertainment when a young child was killed in "A Gun For Christmas" (aired December 21, 1950). The episode followed the search for eight-year-old Stevie Morheim, only to discover he’d been accidentally killed by his best friend while they played with a rifle his friend had received as a Christmas gift. Thousands of letters were mailed to NBC in complaint, including a formal protest by the National Rifle Association. Webb forwarded many of the letters to police chief Parker who promised "ten more shows illustrating the folly of giving rifles to children." (Dunning, 211) "Big Betty" (November 23, 1950) dealt with young women who, rather than finding Hollywood stardom, fall in with fraudulent talent scouts and end up in pornography and prostitution. Template:Endspoiler

The tone was usually serious, but there were moments of comic relief: Romero was something of a hypochondriac and often seemed henpecked; though Friday dated women, he usually dodged those who tried to set him up with marriage-minded dates.

Due in part to Webb’s fondness for radio drama, Dragnet persisted on radio until 1957 as one of the last old time radio shows to give way to television’s increasing popularity. In fact, the TV show would prove to be effectively a visual version of the radio show, as the style was virtually the same. The TV show could be listened to without watching it, with no loss of understanding of the storyline.

Television

When television was interested in Dragnet, Webb bucked the prevailing wisdom which argued that radio staff couldn’t adapt to the new medium. He insisted on hiring radio staff (from actors to writers and production staff) as much as was feasible to work on the television version. This loyalty would endear Webb to many of his Dragnet colleagues for decades to come.

Dragnet first aired on television in January of 1952. Friday's original partner in the TV episodes (as on the radio) was Sgt. Ben Romero, played by Barton Yarborough, who died after only three episodes were filmed. The Romero character was soon replaced by Officer Frank Smith, played by Ben Alexander on both television and radio. Alexander continued in the role through the show's original run, which ended in 1959.

While Dragnet was still on the air, reruns began to air in syndication as Badge 714.

Two other hallmarks of the TV show came at the end of each episode:

- The arrested criminal stands uncomfortably, presumably for the mug shot and the fate of the perpetrators is stated, as a verdict of a court "in and for the City and County of Los Angeles" on an appropriate date.

- A sweaty, glistening left hand appeared, holding what would turn out to be a stamp for indenting metal; a heavy hammer struck the top of the handle of the stamp, twice, loudly; the stamp was removed to reveal the result, "MK VII", referring to the production company, Mark Seven Productions. It would later be revealed that the two hands were in fact, those of Jack Webb [citation needed].

In 1954, a theatrical feature film adaptation of the series was released, with Webb, Alexander, and Richard Boone. In 1966, a TV movie, also called Dragnet, was produced, although it did not air until 1969. Starring Jack Webb and Harry Morgan as his partner Officer Bill Gannon, it spawned a new series, Dragnet 1967, which aired until 1970, the title year changing with each season. Jack Webb had begun the process of bringing Dragnet back to television yet again in 1982, writing and producing five scripts and even picking Kent McCord to play his new partner in "Dragnet '83" before suddenly passing away. After Webb's death, the Chief of the Los Angeles Police Department announced that badge number 714--Webb’s number on the television show--had been retired, and Los Angeles city offices lowered their flags to half-staff.

Remakes

In 1987, a comedy movie version of Dragnet appeared (also titled Dragnet), starring Dan Aykroyd as the stiff Joe Friday (the original Detective Friday's nephew), and Tom Hanks as his partner Pep Streebeck. The film contrasted the terse, clipped character of Friday, a hero from another age, with the 'real world' of Los Angeles in 1987 to broadly parodic effect. Beyond Aykroyd’s effective imitation of Webb’s Joe Friday (and Harry Morgan’s small role reprising his earlier role as Bill Gannon), this film version shares little with the previous incarnations. Although officially a remake, the film was more a parody than a true remake.

In 1989, The New Dragnet appeared in first-run syndication, featuring all-new characters, and aired in tandem with The New Adam-12, a remake of another Webb-produced police drama, Adam-12.

In 2003 another Dragnet series was produced by Dick Wolf, the producer of Law & Order, a series that was strongly influenced by Dragnet. It aired on ABC, and starred Ed O'Neill as Joe Friday and Ethan Embry as Frank Smith. After a 12-episode season that rather closely followed the traditional formula, the format of the series was changed to an ensemble crime drama. Now titled L.A. Dragnet, Friday was promoted to Lieutenant but received less screen time (Frank Smith was written out entirely) in favor of a group of younger and ethnically-diverse detectives (played by Eva Longoria, Christina Chang, Desmond Harrington and Evan Dexter Parke). With most of the trappings that made Dragnet unique no longer in place, it became just another cops and robbers series and it was canceled only five episodes into its second season. Another three episodes aired on USA Network in early 2004, with the final two of the series' 22 episodes remaining unaired in the U.S. until the launch of the Sleuth channel in 2006.

Parodies

Dragnet and its unique presentation style have been referenced or lampooned countless times.

- In the third issue of Mad (January-February, 1953), Harvey Kurtzman and Will Elder offered "Dragged Net!", a parody of the radio series. Since the show had been televised before Mad began, observant readers noted Webb was not caricatured and thus determined that Kurtzman did not yet own a TV set. The comic book's first radio-TV satire came in Mad #11 when Kurtzman and Elder offered a second "Dragged Net!", this time with caricatures. Shortly after Mad's first "Dragged Net!", Stan Freberg recorded "St. George and the Dragon-Net" [F2596] for Capitol Records, selling one million copies in three weeks. He also did his satirical characters on two other recordings, "Little Blue Riding Hood'" and "Christmas Dragnet" [F2671]. In 1954, "Christmas Dragnet" was reissued as "Yulenet" [F2986].

- An early TV appearance of the Three Stooges, a kinescope of which turns up on AMC from time to time, featured a parody of the radio show's style. Each player introduced himself as a name ending in the syllable "day". They went through that schtick several times. In a comic triple, Moe Howard and Larry Fine introduced themselves seriously, as "Halliday" and "Tarraday", and Shemp Howard provided the punch line: "I'm Christmas Day!" or "I'm St. Patrick's Day!" and wearing appropriate garb. They went on to do a routine talking in the deadpan, staccato style of the show. This routine was also captured in their film, Blunder Boys..

- For a Tums commercial, Dragnet's famous four-note-plus-five-note opening theme was used as a jingle ("Tum-Tum-TUM-Tum... Tum-Tum-TUM-Tum-TUMS!"), and Eric Burdon & The Animals also spoofed the show's opening at the beginning of their hit single "San Francisco Nights."

- In The Simpsons episode Mother Simpson Joe Friday and Bill Gannon are parodied as agents during the FBI's search for Homer's mother; Harry Morgan furnished the voice for the animated Bill Gannon.

- Other animated references include Rocket Squad, a futuristic parody with Daffy Duck and Porky Pig as Detectives Monday and Tuesday. Says Monday of Tuesday, "He always follows me."

- On television, Dragnet was the subject of a popular routine (featuring Webb himself and Johnny Carson) on The Tonight Show, and years later as "Mathnet", an ongoing film segment of the PBS series Square One TV. Both the TV series Police Squad and its motion picture spin-offs, the Naked Gun series, parodied elements of the show, particularly the deadpan narration.

- James Ellroy featured a thinly-veiled twist on Dragnet in his L.A. Confidential novel with a popular 1950s' TV police drama, Badge of Honor, which is also seen in the film adaptation of L.A. Confidential. Ellroy’s perspective on Los Angeles cops as crooked and vice-ridden contrasts sharply with Webb’s portrayals of police. The Brett Chase character in Confidential was based on Jack Webb. Among other novels with references to Dragnet is Thomas Pynchon's V.. Pynchon described two minor characters, Patrolman Jones and Officer Ten Eyck, as "faithful viewers of the TV program Dragnet. They'd cultivated deadpan expressions, unsyncopated speech rhythms, monotone voices."

- In Die Hard 2, John McClane sends a fax message to Al Powell. When the girl who sent the fax asks him what he is doing later, McClane thumbs his wedding ring and says, "Just the fax, ma'am, just the fax."

- The avant-garde band The Residents announced a 2006 project, The River of Crime, which is, as their website calls it, "A modern day Dragnet... The series follows the reminisces of its unseen narrator as he discloses a lifelong obsession with wickedness and vice. But, as opposed to the ironic and terse Joe Friday, a classic crime solver, The River of Crime's narrator is a crime collector."

- The character Nick Brick from the 1997 video game LEGO Island has a voice that is an obvious Joe Friday impersonation.

- In the video game "Destroy All Humans" scanning a police officer a few times will bring up the thought "I'm goin' all Joe Friday; I have a dragnet out for evildoers."

- Neil Gaiman's Sandman comic book has two supernatural beings (Loki and Puck) posing as stereotypical police detectives, and they are described by another character in the series as 'Dragnet refugees'.

- Alan Moore's Watchmen graphic novel starts with a murder being investigated by two police detectives, one of which bears a strong resemblance to Jack Webb.

- In War Boy by Thorn Kief Hillsbery, the character Radboy makes a list of satirical names for his impromptu environmental protest group trying to save the redwoods. One is "Rust the Ax Ma'am".

Trivia

- While "just the facts, ma'am" has come to be known as its catch phrase, it was a slight misquote. The closest he came was, "All we want are the facts, ma'am" and "All we know are the facts, ma'am".[1]

- Ethan Embry and Ed O'Neill costarred in the 2003 version of Dragnet. However, this was not the first time they had worked together on a project. They also costarred in a movie several years earlier named Dutch.

- At the end of the original 1950's series, Joe Friday was promoted to Lieutenant. However, in the 1967 sequel, Friday's promotion was never mentioned and he was a Sergeant again. (The character was not demoted onscreen; the promotion was simply ignored as if it never occurred.) As Jack Webb said at the time: "Few people remember that Friday was promoted toward the end of our run. We think it's better to have Joe a sergeant again. Few detective-lieutenants get out into the field." Later, in the second season of the 2003 remake, Friday was promoted to Lieutenant for real.

Notes

Sources

- John Dunning, On The Air: The Encyclopedia of Old-Time Radio, Oxford University Press, 1998, ISBN 0-19-507678-8.

- Jason Mittell, Genre and Television: From Cop Shows to Cartoons in American Culture. Routledge, 2004, ISBN 0-415-96903-4.

External links

- The 1951-59 series at IMDb

- "Dragnet 1967" at IMDb

- "The New Dragnet" at IMDb

- "Dragnet (2003)" at IMDb

- Badge714.com - Information on all Dragnet shows and the works of Jack Webb.

- Dragnet (1951) at TV.com

- Dragnet (1967-1970) at TV.com

- Dragnet (1989) at TV.com

- L.A. Dragnet (2003-2004) at TV.com

- 1951 television program debuts

- 1950s TV shows in the United States

- 1954 films

- 1960s TV shows in the United States

- 1980s TV shows in the United States

- 2000s TV shows in the United States

- ABC network shows

- Crime television series

- NBC network shows

- American radio programs

- Television series by NBC Universal Television

- Edgar Award winning works