Gadfly (philosophy and social science)

| Part of a series on |

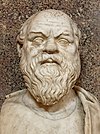

| Socrates |

|---|

|

| Eponymous concepts |

| Pupils |

| Related topics |

|

|

Gadfly is a word which is used both; to describe a group of insects, and as an attachment of identification of the behaviour of an insect of the group to the identification of individuals in the modern social environ specifically only as a semantic association rooted to an ancient greek classical idea in the seminal speech communicated by the literary Socrates in Apology of Socrates written by Plato, to identify people with regards to the status quo of a society or community, metaphorically, as the concept of an individual who "stings" a society or its leaders by challenging their beliefs and behaviors, the greek classical era idea being Socrates a fly stings Athens a horse.

Gadfly as actual insects

Gadfly is a word which describes certain types of insects [1] specifically those parasitic [2] to a number of rurally dwelling animals, ordinarily, including humans extraordinarily; termed gadflies, [3] such as the warble-fly, botfly, [4][5] and horse fly. [1][6][5]

Origination of the idea

Ancient Greece

Socrates

The idea of Socrates being and behaving as a type of fly, [7][8] translated from ancient Greek into the English language specifically as "gadfly", is understood in the sense "gadfly" [9] as an epitheton of Socrates, [10] because the idea was used as a simile, [11] and a metaphor, [12][13] by Plato within 30e-31a [14] of Apology:[15]

...ὑμῖν ἐμοῦ καταψηφισάμενοι. ἐὰν γάρ με ἀποκτείνητε, οὐ ῥᾳδίως ἄλλον τοιοῦτον εὑρήσετε, ἀτεχνῶς—εἰ καὶ γελοιότερον εἰπεῖν—προσκείμενον τῇ πόλει ὑπὸ τοῦ θεοῦ ὥσπερ ἵππῳ μεγάλῳ μὲν καὶ γενναίῳ, ὑπὸ μεγέθους δὲ νωθεστέρῳ καὶ δεομένῳ ἐγείρεσθαι ὑπὸ

— 30e [14]

μύωπός τινος, οἷον δή μοι δοκεῖ ὁ θεὸς ἐμὲ τῇ πόλει προστεθηκέναι τοιοῦτόν τινα, ὃς ὑμᾶς ἐγείρων καὶ πείθων καὶ ὀνειδίζων ἕνα ἕκαστον οὐδὲν παύομαι τὴν ἡμέραν ὅλην πανταχοῦ προσκαθίζων.τοιοῦτος οὖν ἄλλος οὐ...

— 31a [14]

to describe Socrates vis-à-vis [7] the city-state Athens. [16][7] The idea is expressed as Athens being analogous to a horse, [7] ἵππῳ, within the second line of 30e, [17] with Socrates the insect, [7] μύωπός, within the first line of 31a, [17] as part of the defence [18] (the word << defence >> in the language Latin being [19] apologia [20]) made by Socrates of his own self against accusations made against him in his trial, [18] of 399 B.C., for the infraction impiety. [21]

In Apology (Fowler translated, 1966), Socrates posits the horse-Athens needs to be stung. [22] In Plato [23] Meno, Socrates is cast as a stingray, [24] or, stinging torpedo fish, [25] which stings both others, and also Socrates, making both Socrates and others numb, all caused by the activity of Socrates's questions (Socratic questioning). [23] This is a some times evident fact of existence, that the existence of the fact of a thought, or of thoughts, contemplation, [26] in response to a question or questions, [23] in the mind, sometimes causes a type of paralysis [26](Latin: aporia, [27] transliterated Greek: narkōsa (others), narkan (itself), within Meno 80c [25]), this paralysis, [26] being the same experience as numbness,[23] being the same thing as the need to stop to think in order to dwell in thought, to ponder, and, or, to contemplate. [26] Comparing Apology, in which Socrates states he is a fly stinging a horse, because of the "sluggishness" of the horse, [22] to Meno, though the effect of the two stings in both examples (Meno & Apology) is opposite, the similitude in both is the pain of a sting being the same as pain of new self-awareness of ignorance, caused by Socrates, being the [24] knowing of belief being not knowable, compared to knowledge. [27]

Bible

The Book of Jeremiah uses a similar analogy as a political[citation needed] metaphor: "Egypt is a very fair heifer; the gad-fly cometh, it cometh from the north" (46:20, Darby Bible).

gadfly as a participating member of the English language

The precedent word gad, existed in the 13th century England, amongst words of the Middle English language. [28]

Past English language translation and usage

One of, or perhaps the first importers, of Plato Apology to England was Humphrey of Gloucester (a Duke of England), who during 1439 benefacted the University of Oxford with a Latin language Bruni version of Apology. [29] During 1473 John Gunthorpe, who had accompanied to Italy John Tiptoft, both had followed a brief succession of periodic travellers, after Grey, to Italy, returned to England with a Bruni 1423 copy of the text. [30]

Infact, during the interim 1451 to 1578 not much works of Plato existed in England. [30] A first edition of Apology (England) exists from 1675, prior to the 1600's, the oeuvre of Plato totum was virtually unknown of within England nationally, at least by the measure of reading alone. [31] This is because [31][32] individuals born within England choosing tourism of Italy as a preference (as Chaucer did during 1373) are almost factually absent from history until the 1600's, when Renaissance developments spurred interest. [32][33]

Development of the gadfly idea

Ancient Roman

The poet [34] Ovid, [35] born 43 B.C., [34] used the idea [36] within book 1 of [37] the epic[38] narrative [39] Metamorphoses,[36] in which he substitutes the disturbing fly for furor [37] (madness [40][41]) which never-the-less is ultimately the same thing, [42][43] a literary expression of an idea, of torment sent by Olympian gods [44]

Recent past usage

The concept of "a gadfly" exists because of the behaviour of [45][46] insect(s), [47][48] which is used to identify a particular type of behaviour in people. [45][46]

In modern politics, a gadfly is someone who persistently challenges people in positions of power, the status quo or a popular position.[49] For example, Morris Kline wrote, "There is a function for the gadfly who poses questions that many specialists would like to overlook. Polemics is healthy."[50] The word may be uttered in a pejorative sense or be accepted as a description of honourable work or civic duty.[51]

See also

References

P. J. Rhodes (2011) — A History of the Classical Greek World: 478 - 323 BC, published by John Wiley & Sons, 24 August 2011, Volume 11 of Blackwell History of the Ancient World ISBN 1444358588, ISBN 9781444358582 - accessed 2020-02-18 (this reference is not associated to content by copy, is included here to indicate "classical era")

Sources

- ^ a b Kenneth F Kitchell Junior (2014) — Animals in the Ancient World from A to Z, p.91, published by Routledge June 23 2014 ISBN 1317577434, ISBN 9781317577430 - accessed 2020-01-27, re-accessed 2020-02-12

- ^ P. E. Kaufman, P. G. Koehler, and J. F. Butler — External Parasites on Horses, United States Department of Agriculture, UF/IFAS Extension Service, University of Florida, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences (IFAS), Florida A & M University Cooperative Extension Program - accessed 2020-02-11

- ^

- William Kirby &, William Spence — An Introduction to Entomology, or Elements of the Natural History of the Insects, Volume I of IV, (inline referent 218), republished by Google, ISBN 1465583106, ISBN 9781465583109 - accessed 2020-02-12

- (Kirby & Spence (1818) — Volume I - Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme & Brown (1818; 3rd edition), republished by Biodiversity Heritage Library - accessed 2020-02-12)

- ^

- "bot-fly, warble-fly" - Schneider & Williams, in, (Bo Carlsson, Susanna Hedenborg editors) The Social Science of Sport: A Critical Analysis, On the evaluation of quality: metaphors (i), published by Routledge October 24 2018 (reprint), ISBN 1317450558, ISBN 9781317450559 - accessed 2020-01-28, retrieved 2020-02-12

- "warble fly"

- Asle Rønning (2013) — infections norway, published by forskning.no May 15 2013 - accessed 2020-02-12

- Sdobnikov (1935), used by Adolph Murie, in p.159 of Fauna of the National Parks of the United States: Fauna series - United States Government Printing Office 1944 - accessed 2020-02-12

- R.V. Short, in, (Colin Russell Austin, Roger Valentine, editors) — Hormonal Control of Reproduction, pp.115-116, published by Cambridge University Press 1984 (reprint), ISBN 0521275946, ISBN 9780521275941 - accessed 2020-1-30, re-accessed & retrieved 2020-02-12

- "bot-fly" - Aharon B. Dolgopolsky (2004) — p.419 in (Werner Vycichl, Gâabor Takâacs; editors) Egyptian and Semito-Hamitic (Afro-Asiatic) Studies: In Memoriam W. Vycichl, published by BRILL 2004 ISBN 9004132457, ISBN 9789004132450 - accessed 2020-02-12

- ^ a b Merriam-Webster definition, in, Tamler Sommers (2016; revised 2nd edition) — Chapter 9 Peter Singer A Gadfly for the Greater Good - Chapter 9 (source doesn't show page numbers) in, A Very Bad Wizard: Morality Behind the Curtain, published by Routledge 26 May 2016, ISBN 1135108439, ISBN 9781135108434 - accessed 2020-02-17 (source is not associated to content by copy)

- ^ David John Farmer (2005) — To Kill the King: Post-traditional Governance and Bureaucracy, p.21 published by M.E. Sharpe 2005 ISBN 0765614804, ISBN 9780765614803 (page 21 shows a quotation by Umberto Eco) - accessed 2020-02-17 (source is not associated to content by copy)

- ^ a b c d e Paul Allen Miller, Charles Platter (2012) — Plato's Apology of Socrates: A Commentary, p.93, published by University of Oklahoma Press November 13 2012, ISBN 0806186054, ISBN 9780806186054 - accessed 2020-2-1 (source Google, shows errata: "fiction")

- ^ Laura Marshall (2019) — Not a Gadfly: When a Crucial Reading Goes Wrong, Ohio State University 2019, Society for Classical Studies, - accessed 2020-01-27 (sourced using: "μύωψ in 30e")

- ^ Laura A. Marshall (2017) — Gadfly or Spur? The Meaning of ΜΎΩΨ in Plato’s Apology of Socrates, published online by Cambridge University Press: 07 November 2017, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S007542691700012X - re-accessed 2020-2-1

- ^ Hjördis Becker-Lindenthal (2014), in, (Katalin Nun, Dr Jon Stewart; editors) — Volume 16, Tome I: Kierkegaard's Literary Figures and Motifs: Agamemnon to Guadalquivir, p.259, published by Ashgate Publishing Ltd., 28 October 2014 (revised) ISBN 1472441362, ISBN 9781472441362 - accessed 2020-01-27 (sourced using "Socrates the gadfly"

- ^ John P. Harris (2019) — Flies, Wasps, and Gadflies: The Role of Insect Similes in Homer, Aristophanes, and Plato, Volume 15 Issue 3 of Mouseion 2018, LIX–Series III, pp. 475-500, published by the University of Toronto Press online February 11, 2019, DOI: 10.3138/mous.15.3-09 - accessed 2020-1-30, re-accessed 2020-1-31

- ^

- Ann Hartle (1986) — Death and the Disinterested Spectator: An Inquiry into the Nature of Philosophy, p.14, published by SUNY Press January 1 1986, ISBN 0887062857, ISBN 9780887062858 - accessed 2020-1-31

- Schneider & Williams (2018), in, (Bo Carlsson, Susanna Hedenborg editors) — The Social Science of Sport: A Critical Analysis, On the evaluation of quality: metaphors (i), published by Routledge October 24 2018 (reprint), ISBN 1317450558, ISBN 9781317450559 - accessed 2020-01-28

- Bibliographical: verification of the difference between simile and metaphor: Clive Scott (1986) - A Question of Syllables: Essays in Nineteenth-Century French Verse, pp.61-2, published by Cambridge University Press September 11 1986, ISBN 0521325846, ISBN 9780521325844 - accessed 2020-1-31

- ^ H. Peter Steeves (2015) — (p.107 of) The Dog on the Fly, in, (Jeremy Bell, Michael Naas; editors) — Plato's Animals: Gadflies, Horses, Swans, and Other Philosophical Beasts, published by Indiana University Press May 1 2015, ISBN 0253016207, ISBN 9780253016201 Studies in Continental Thought - accessed 2020-1-28, (p.107 accessed 2020-1-31) (sourced using "Socrates gadfly")

- ^ a b c Apology 30e-31a: Πλάτωνος, republished within the Perseus Project - published by University of Chicago - accessed 2020-1-27, re-accessed 2020-1-28 - (greek language in this source sourced from Aristotle University (of Thessaloniki), Library and Information Centre (search criteria return) - accessed 2020-2-2

- ^ "Apology 30e".

- ^ Raphael Sealey (1976) — A History of the Greek City States, 700-338 B. C., p.89, University of California Press October 28 1976, ISBN 0520031776, ISBN 9780520031777, - accessed 2020-1-28

- ^ a b Pocket Oxford Classical Greek Dictionary, (edited by James Morwood & John Taylor), published by Oxford University Press 2002 (1st edition), p.388, p.390, p.394 ISBN 9780198605126 - "μυîα" accessed & re-accessed 2020-1-29, all other words accessed 2020-1-29

- ἵππῳ - horse

- μύωπός - fly

Modern Greek (via https://www.lexilogos.com/english/greek_dictionary.htm):

- "fly" = μύγα — systran.net, published by SYSTRAN February 2, 2020 - accessed 2020-2-2

- "a fly" = μια μύγα — bing.com, published by Microsoft February 2, 2020 - accessed 2020-2-2

- "horse" = άλογο — systran.net, published by SYSTRAN February 2, 2020 - accessed 2020-2-2

- ^ a b Thomas C. Brickhouse, Nicholas D. Smith (1990) — Socrates on Trial, pp.62-3, published by Clarendon Press 1990 (reprint, revised), ISBN 0198239386, ISBN 9780198239383 - accessed 2020-2-1 (source added after content)

- ^ "apologia is Latin": https://glosbe.com/en/la/apologia, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/apologia (shows errata: "First known use ... 1784") c.f. "..Justin uses apologia.." p.24 of; Laura Salah Nasrallah - Christian Responses to Roman Art and Architecture: The Second-Century Church Amid the Spaces of Empire, published by Cambridge University Press January 25 2010, - accessed 2020-1-31

- ^

verification of "...defence used by Socrates"

- Plato (c. 427– c. 347 B.C.), published by Barnes & Noble, - accessed 2020-1-31 (source shows errata: "..A defense speech in Greek is apologia..")

- Charles Platter — Plato’s Apology of Socrates, DOI: 10.1093/OBO/9780195389661-0165, published by Oxford University Press, - accessed 2020-1-31 (errata: source shows "Greek, apologia")

- "apologia is Latin": https://glosbe.com/en/la/apologia, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/apologia (errata: "First known use ... 1784", c.f. idem Nasrallah (2010) - p.24)

- ^ (Nicholas D. Smith, Paul Woodruff, editors; 2000) — Reason and Religion in Socratic Philosophy, pp.3-4, published by Oxford University Press November 16 2000, ISBN 0195350928, ISBN 9780195350920 - accessed 2020-1-29, re-accessed 2020-2-1

- ^ a b

- Plato in Twelve Volumes, Vol. 1 translated by Harold North Fowler, Plato — Apology Cambridge, Massacheusetts, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1966 - accessed 2020-1-27

- [30e]:"...to use a rather absurd figure, attaches himself to the city as a gadfly to a horse, which, though large and well bred, is sluggish on account of his size and needs to be aroused by stinging. I think the god fastened me upon the city in some such capacity, and I go about arousing"

- [31a]:"and urging and reproaching each one of you..."

- Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott — A Greek-English Lexicon - accessed 2020-1-27

- Plato in Twelve Volumes, Vol. 1 translated by Harold North Fowler, Plato — Apology Cambridge, Massacheusetts, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1966 - accessed 2020-1-27

- ^ a b c d Gareth B. Matthews (2003) — Socratic Perplexity and the Nature of Philosophy, p.87.90, published by Oxford University Press 2003, ISBN 0198238886, ISBN 9780198238881 - accessed 2020-2-1

- ^ a b Joel Alden Schlosser (2009) — Engaging Socrates, pp.37-8 (source) pp.44-45 of Microsoft Word (https://dukespace.lib.duke.edu/), published by Duke University (Department of Political Science) - accessed 2020-2-1

- ^ a b Jan Szaif (2018) — p.37 of, Socrates and the benefits of puzzlement, in, (George Karamanolis, Vasilis Politis editing) — The Aporetic Tradition in Ancient Philosophy, published by Cambridge University Press 2018, ISBN 1107110157, ISBN 9781107110151 - accessed 2020-2-1 (c.f. torpid)

- ^ a b c d (Hannah Arendt), Antonio Calcagno (2015) — p.121 of, Finding a place for desire in the life of the mind Arendt and Augustine, in, Thinking About Love: Essays in Contemporary Continental Philosophy, published by Penn State Press 6 November 2015, (Diane Enns, Antonio Calcagno, editors) ISBN 0271076186, ISBN 9780271076188 - accessed 2020-2-1

- ^ a b Agnes Gellen Callard (2014) — p.69 of, Ignorance and Akrasia-Denial in the Protogoras, in, Brad Inwood (2014) — Oxford Studies in Ancient Philosophy, Volume 47, published Oxford University Press November 13 2014, ISBN 0198722710, ISBN 9780198722717 - accessed 2020-2-1

- ^ Walter William Skeat - "M.E. — (Middle English English from the thirteenth to the fifteenth centuries inclusive)..".."gad (I) a wedge of steel, goad...M.E. gad a goad" — The Concise Dictionary of English Etymology, pp.xi179, published by Wordsworth Editions 1993 (reprint) ISBN 1853263117, ISBN 9781853263118 - accessed 2020-01-27

- ^ Abstracts of Theses: Humanistic series, published by University of Chicago Press 1925 "Duke Humphrey of Gloucester (1391-1447) in 1439 gave the University of Oxford the Latin translation of the Phaedrus, Phaedo, Gorgias, Apology, and Crito by Bruni. In the same ... Various scholars went to Italy, as Grey, Free, Gunthorpe, Tiptoft." - accessed 2020-2-4 (using search criteria (within Google) "Grey Gunthorpe. Plato Apology")

- ^ a b Sears Jayne (2013) — Plato in Renaissance England, pp.19-20,21, published by Springer Science & Business Media June 29 2013, ISBN 9401585512, ISBN 9789401585514, Archives internationales d'histoire des idées - accessed 2020-2-3 , re-accessed 2020-2-4 (pages not available at source 2020-2-4, see next source shown here (using criteria "Grey Gunthorpe. Plato Apology") → (Jayne 2013) → "There is no evidence that Grey's acquaintance with the greatest Plato scholar on the continent had any influence on ... As we have seen, Grey was followed at Ferrara in 1447 by Robert Flemming, in 1456 by John Free (R. Mitchell, 1955), and in 1459 by John Tiptofi and John Gunthorpe. ... Apology (Bruni translation; 2nd version) Crito (Bruni translation; 2nd version) Timaeus (Calcidius translation) (See ..."

- ^ a b "#:71680", published by Bauman Rare Books - accessed 2020-2-3 ("..remained relatively unread in England until the 17th century..John Brinsley in 1612 could complain that there was no English translation of any of Plato’s works in print for students to use in translation exercises...") - re-accessed 2020-2-4

- ^ a b Charles Peter Brand (1957) — Italy and the English Romantics: The Italianate Fashion in Early Nineteenth-century England, p.7, published by Cambridge University Press 1957, - accessed 2020-2-4

- ^ (search criteria: "tours of Italy noble men" > Andrew Wilton, Ilaria Bignamini (published by the Tate gallery 1996 "Grand Tour" > Edward Chaney — The Evolution of the Grand Tour: Anglo-Italian Cultural Relations Since the Renaissance, published 2000 (revised reprint) by Taylor & Francis, ISBN 0714644749, ISBN 9780714644745 (both sources accessed 2020-2-4)(sources added after content)

- ^ a b Niklas Holzberg (2002) — Ovid: The Poet and His Work, p.23, published by Cornell University Press 2002 - accessed 2020-02-16

- ^ Roman & Roman (2010) ISBN 1438126395, ISBN 9781438126395 - accessed 2020-02-16

- ^ a b Luke Roman, Monica Roman (2010) — Encyclopedia of Greek and Roman Mythology, p.266, published by Infobase Publishing 2010 ISBN 1438126395, ISBN 9781438126395 (https://classics.stanford.edu/people/luke-roman) - accessed 2020-02-16 using "Zeus Io Hera gadfly" from: http://www.gadflyonline.com/home - accessed 2020-02-03, http://gadflyonline.com/home/index.php/about-3/ published by Gadfly Productions - accessed 2020-02-03, re-accessed 2020-02-16

- ^ a b Ovid's Metamorphoses, Books 1-5: Book 1 The Release of Io from Torment; Notes 724-31 (Io) by William S. Anderson (1997 reprint, revised) — p.219, published by University of Oklahoma Press 1997, ISBN 0806128941, ISBN 9780806128948 The American philological association series of classical texts - accessed 2020-02-16

- ^ Genevieve Liveley (2011) — Ovid's 'Metamorphoses': A Reader's Guide, p.8, published by Bloomsbury Publishing 24 Feb 2011 ISBN 1441100849, ISBN 9781441100849 - accessed 2020-02-16, from Jaclyn Neil (2017; 1st edition) — Early Rome: Myth and Society, pp.8-9, published John Wiley & Sons May 1 2017 ISBN 111908380X, ISBN 9781119083801 Blackwell Sourcebooks in Ancient History - accessed 2020-02-16

- c.f.

- Neil (p.8): "Elegiac poetry differs from epic in both meter and typical subject matter..."

- Liveley (p.9):"..his elegiacally epic Metamorphosis.." (& p.3)

- c.f.

- ^ Ovid’s Metamorphoses, published by the British Library - accessed 2020-02-16

- ^ NW Bernstein (2011) —Locus Amoenus and Locus Horridus in Ovid's Metamorphoses, p.68, published by The Wenshan Review of Literature and Culture in Volume 5.1 December 2011 - accessed & re-accessed 2020-02-16

- ^ Stephen Michael Wheeler (2000) — Narrative Dynamics in Ovid's Metamorphoses, p.62, published by Gunter Narr Verlag 2000, ISBN 3823348795, ISBN 9783823348795, Volume 20 of Classica monacensia : Münchener Studien zur Klassischen Philologie - accessed 2020-02-16

- c.f.

- Wheeler (p.62): "Ovid thus re-shape's Io's story...stems from self-horror rather than the sting...repeat's the theme of Io's fear and flight...Juno harrasses Io with a Fury (1.725, Erinys) and ..(726, stimulosque in pectore caecos).."

- William S. Anderson (p.219): "..substitutes a Fury for the gadfly.."

- c.f.

- ^ Michael Naas (2015; reprint) — p.49 "..The sting or goad of the gadfly...drives one mad..", of American Gadfly, in, Plato's Animals: Gadflies, Horses, Swans, and Other Philosophical Beasts (edited by Jeremy Bell, Michael Naas), published by Indiana University Press May 1 2015 ISBN 0253016207, ISBN 9780253016201 - accessed 2020-02-16

- ^ Michel Erler (2017) — Mania and knowledge. From the sting of the gods to Socrates as educational gadfly, published in the Journal of Educational Philosophy and Theory by Taylor and Francis (online) 8 December 2017, https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2017.1373339 - accessed 2020-02-16

- ^ John T Hamilton (2008) — Music, Madness, and the Unworking of Language, p.36, published by Columbia University Press May 6 2008, ISBN 0231512546, ISBN 9780231512541 Columbia Themes in Philosophy, Social Criticism, and the Arts - accessed 2020-02-16 - "...the other species of Olympian-sent sufferings, which on the whole are characterized by an attack from without..."

- c.f. Konstantinov SA, Veselkin AG (1989; subsequently translated to English) — The intensity and efficiency of a gadfly attack on cattle depending on the number and location of the animals in the herd, Parazitologiia 1989 January-February;23(1):3-10, PMID: 2524028, re-accessed 2020-02-16

- ^ a b Chambers concise dictionary, p.477, published by Allied Publishers 2004, ISBN 9798186062363 - 2020-2-1

- ^ a b Paperback Oxford English Dictionary, p.295, published by Oxford University Press 10 May 2012, ISBN 0199640947, ISBN 9780199640942 (Maurice Waite, editor) - accessed 2020-2-1

- ^ Kenneth F Kitchell Junior (2014) — Animals in the Ancient World from A to Z, p.91, published by Routledge June 23 2014 ISBN 1317577434, ISBN 9781317577430 - accessed 2020-01-27

- ^ Schneider & Williams (2018), in, (Bo Carlsson, Susanna Hedenborg editors) — The Social Science of Sport: A Critical Analysis, On the evaluation of quality: metaphors (i), published by Routledge October 24 2018 (reprint), ISBN 1317450558, ISBN 9781317450559 - accessed 2020-01-28

- ^ Liberto, Jennifer (2007-08-08). "Publix uses law to boot gadfly". St. Petersburg Times. Retrieved 2008-06-22.

- ^ Why the Professor Can't Teach (1977), page 238

- ^ "The Gadfly". BBC – h2g2. 2004-10-06. Retrieved 2008-06-22.

Bibliographiy

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/124845 - accessed 2020-02-12

- Aristotle, in, N. Papavero (2012) — The World Oestridae (Diptera), Mammals and Continental Drift, p.10, published Springer Science & Business Media December 6 2012 - accessed 2020-02-12

- https://logeion.uchicago.edu/ (μυωπός, et cetera) - accessed 31 January 2020, retrieved 2020-02-12

- Jeremy Bell (2015) — p.115 of Taming Horses and Desires Plato's politics of care, in, (Jeremy Bell, Michael Naas; editors) — Plato's Animals: Gadflies, Horses, Swans, and Other Philosophical Beasts, published by Indiana University Press May 1 2015, ISBN 0253016207, ISBN 9780253016201 Studies in Continental Thought - accessed 2020-1-28 (sourced using "Socrates gadfly"); retrieved 2020-02-12

- Demetrios Moutsos (1980) — Greek μύωψ and τζιμούριον Zeitschrift für vergleichende Sprachforschung 4. Bd., 1./2. H. (1980), pp. 147-157, published by Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht (GmbH & Co. KG) - accessed 2020-01-27 - accessed 2020-01-27, retrieved 2020-02-12

- Aristotle, Lilian Bodson (October - November 1983) "..all agree that Aristotle was the first scholar to give an extensive account of these smallest of creatures... or, at least, to compile and enlarge upon what was already known about them (Byl, 1980; Chroust 1973; Grayeff 1956).." — The beginnings of Entomology in Ancient Greece, The Classical Outlook Volume 61, No. 1 - accessed 2020-01-27, retrieved 2020-02-12

- Richard C. Russell, Domenico Otranto, Richard L. Wall (2013) — The Encyclopedia of Medical and Veterinary Entomology, Stomach Bot Flies (Diptera: Oestridae, Gasterophilinae, p.325, published by CABI 2013 - accessed 2020-1-30, retrieved 2020-02-12

- https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/cattle - accessed 2020-02-13

- D Konstan (2009) - The Active Reader and the Ancient Novel, in, Readers and Writers in the Ancient Novel, Barkhuis 2009 ISBN 9077922547, ISBN 9789077922545 - accessed 2020-02-16

- Elizabeth Norton (2014; reprint) — Aspects of Ecphrastic Technique in Ovid's Metamorphoses,p.136, Cambridge Scholars Publishing (https://www.cambridgescholars.com/t/AboutUs) 11 August 2014, ISBN 1443865478, ISBN 9781443865470 - accessed 2020-02-16 "..Like the gadfly, Allecto will inspire furor.."

- Daniel W. Chaney — Table 2 Behavior words, defined and listed chronologically, in, An Overview of the First Use of the Terms Cognition and Behavior, published in Behavior Sciences (Basel), 2013 March; 3(1): 143–153, published online 2013 February 7, doi: 10.3390/bs3010143 PMCID: PMC4217620 PMID: 25379231 - accessed 2020-02-18

External links

The dictionary definition of gadfly at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of gadfly at Wiktionary