Git: Difference between revisions

No access controls →Security |

→Security: Aligning the text more closely with RS. |

||

| Line 272: | Line 272: | ||

== Security == |

== Security == |

||

Git |

Git does not provide access control mechanisms, but was designed for operation with other tools that specialize in access control.<ref>https://wincent.com/wiki/git_repository_access_control</ref> |

||

On 17 December 2014, an exploit was found affecting the [[Microsoft Windows|Windows]] and [[OS X|Mac]] versions of the Git client. An attacker could perform [[arbitrary code execution]] on a Windows or Mac computer with Git installed by creating a malicious Git tree (directory) named ''.git'' (a directory in Git repositories that stores all the data of the repository) in a different case (such as .GIT or .Git, needed because Git doesn't allow the all-lowercase version of ''.git'' to be created manually) with malicious files in the ''.git/hooks'' subdirectory (a folder with executable files that Git runs) on a repository that the attacker made or on a repository that the attacker can modify. If a Windows or Mac user "pulls" (downloads) a version of the repository with the malicious directory, then switches to that directory, the .git directory will be overwritten (due to the case-insensitive nature of the Windows and Mac filesystems) and the malicious executable files in ''.git/hooks'' may be run, which results in the attacker's commands being executed. An attacker could also modify the ''.git/config'' configuration file, which allows the attacker to create malicious Git aliases (aliases for Git commands or external commands) or modify existing aliases to execute malicious commands when run. The vulnerability was patched in version 2.2.1 of Git, released on 17 December 2014, and announced on the next day.<ref>{{cite web|url = https://developer.atlassian.com/blog/2014/12/securing-your-git-server/|title = Securing your Git server against CVE-2014-9390|date = 20 December 2014|accessdate = 22 December 2014|website = |publisher = |last = Pettersen|first = Tim}}</ref><ref>{{cite newsgroup |title=[ANNOUNCE] Git v2.2.1 (and updates to older maintenance tracks) |author= Hamano, J. C.|date= 18 December 2014|newsgroup=gmane.linux.kernel |url=http://article.gmane.org/gmane.linux.kernel/1853266 |access-date=22 December 2014}} {{dead link|date=July 2016}}</ref> |

On 17 December 2014, an exploit was found affecting the [[Microsoft Windows|Windows]] and [[OS X|Mac]] versions of the Git client. An attacker could perform [[arbitrary code execution]] on a Windows or Mac computer with Git installed by creating a malicious Git tree (directory) named ''.git'' (a directory in Git repositories that stores all the data of the repository) in a different case (such as .GIT or .Git, needed because Git doesn't allow the all-lowercase version of ''.git'' to be created manually) with malicious files in the ''.git/hooks'' subdirectory (a folder with executable files that Git runs) on a repository that the attacker made or on a repository that the attacker can modify. If a Windows or Mac user "pulls" (downloads) a version of the repository with the malicious directory, then switches to that directory, the .git directory will be overwritten (due to the case-insensitive nature of the Windows and Mac filesystems) and the malicious executable files in ''.git/hooks'' may be run, which results in the attacker's commands being executed. An attacker could also modify the ''.git/config'' configuration file, which allows the attacker to create malicious Git aliases (aliases for Git commands or external commands) or modify existing aliases to execute malicious commands when run. The vulnerability was patched in version 2.2.1 of Git, released on 17 December 2014, and announced on the next day.<ref>{{cite web|url = https://developer.atlassian.com/blog/2014/12/securing-your-git-server/|title = Securing your Git server against CVE-2014-9390|date = 20 December 2014|accessdate = 22 December 2014|website = |publisher = |last = Pettersen|first = Tim}}</ref><ref>{{cite newsgroup |title=[ANNOUNCE] Git v2.2.1 (and updates to older maintenance tracks) |author= Hamano, J. C.|date= 18 December 2014|newsgroup=gmane.linux.kernel |url=http://article.gmane.org/gmane.linux.kernel/1853266 |access-date=22 December 2014}} {{dead link|date=July 2016}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 21:36, 6 September 2016

| |

A command-line session showing repository creation, addition of a file, and remote synchronization | |

| Original author(s) | Linus Torvalds[1] |

|---|---|

| Developer(s) | Junio Hamano and others[2] |

| Initial release | 7 April 2005 |

| Stable release | 2.10

/ 2 September 2016 |

| Repository | |

| Written in | C, Shell, Perl, Tcl and Python[3] |

| Operating system | Linux, Windows, OS X |

| Platform | POSIX |

| Type | Version control |

| License | GNU GPL v2[4] and GNU LGPL v2.1[5] |

| Website | git-scm |

Git (/ɡɪt/[6]) is a version control system that is used for software development[7] and other version control tasks. As a distributed revision control system it is aimed at speed,[8] data integrity,[9] and support for distributed, non-linear workflows.[10] Git was created by Linus Torvalds in 2005 for development of the Linux kernel, with other kernel developers contributing to its initial development.[11]

As with most other distributed version control systems, and unlike most client–server systems, every Git directory on every computer is a full-fledged repository with complete history and full version-tracking capabilities, independent of network access or a central server.[12] Like the Linux kernel, Git is free software distributed under the terms of the GNU General Public License version 2.

History

Git development began in April 2005, after many developers of the Linux kernel gave up access to BitKeeper, a proprietary source control management (SCM) system that they had previously used to maintain the project.[13] The copyright holder of BitKeeper, Larry McVoy, had withdrawn free use of the product after claiming that Andrew Tridgell had reverse-engineered the BitKeeper protocols.[14]

Torvalds wanted a distributed system that he could use like BitKeeper, but none of the available free systems met his needs, particularly in terms of performance. Torvalds cited an example of a source-control management system requiring 30 seconds to apply a patch and update all associated metadata, and noted that this would not scale to the needs of Linux kernel development, where syncing with fellow maintainers could require 250 such actions at a time. For his design criteria, he specified that patching should take no more than three seconds,[8] and added three additional points:

- Take Concurrent Versions System (CVS) as an example of what not to do; if in doubt, make the exact opposite decision[10]

- Support a distributed, BitKeeper-like workflow[10]

- Include very strong safeguards against corruption, either accidental or malicious[9]

These criteria eliminated every then-existing version-control system except Monotone. Performance considerations excluded this, too.[10] So immediately after the 2.6.12-rc2 Linux kernel development release, Torvalds set out to write his own system.[10]

Torvalds quipped about the name git (which means "unpleasant person" in British English slang): "I'm an egotistical bastard, and I name all my projects after myself. First 'Linux', now 'git'."[15][16] The man page describes Git as "the stupid content tracker".[17] The readme file of the source code elaborates further:[18]

The name "git" was given by Linus Torvalds when he wrote the very

first version. He described the tool as "the stupid content tracker"

and the name as (depending on your mood):

- random three-letter combination that is pronounceable, and not

actually used by any common UNIX command. The fact that it is a

mispronunciation of "get" may or may not be relevant.

- stupid. contemptible and despicable. simple. Take your pick from the

dictionary of slang.

- "global information tracker": you're in a good mood, and it actually

works for you. Angels sing, and a light suddenly fills the room.

- "goddamn idiotic truckload of sh*t": when it breaks

The development of Git began on 3 April 2005.[19] Torvalds announced the project on 6 April;[20] it became self-hosting as of 7 April.[19] The first merge of multiple branches took place on 18 April.[21] Torvalds achieved his performance goals; on 29 April, the nascent Git was benchmarked recording patches to the Linux kernel tree at the rate of 6.7 per second.[22] On 16 June Git managed the kernel 2.6.12 release.[23]

Torvalds turned over maintenance on 26 July 2005 to Junio Hamano, a major contributor to the project.[24] Hamano was responsible for the 1.0 release on 21 December 2005, and remains the project's maintainer.[25]

| Version | Original release date | Latest version | Release date |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.99 | 2005-07-11 | 0.99.9n | 2005-12-15 |

| 1.0 | 2005-12-21 | 1.0.13 | 2006-01-27 |

| 1.1 | 2006-01-08 | 1.1.6 | 2006-01-30 |

| 1.2 | 2006-02-12 | 1.2.6 | 2006-04-08 |

| 1.3 | 2006-04-18 | 1.3.3 | 2006-05-16 |

| 1.4 | 2006-06-10 | 1.4.4.5 | 2008-07-16 |

| 1.5 | 2007-02-14 | 1.5.6.6 | 2008-12-17 |

| 1.6 | 2008-08-17 | 1.6.6.3 | 2010-12-15 |

| 1.7 | 2010-02-13 | 1.7.12.4 | 2012-10-17 |

| 1.8 | 2012-10-21 | 1.8.5.6 | 2014-12-17 |

| 1.9 | 2014-02-14 | 1.9.5 | 2014-12-17 |

| 2.0 | 2014-05-28 | 2.0.5 | 2014-12-17 |

| 2.1 | 2014-08-16 | 2.1.4 | 2014-12-17 |

| 2.2 | 2014-11-26 | 2.2.3 | 2015-09-04 |

| 2.3 | 2015-02-05 | 2.3.10 | 2015-09-29 |

| 2.4 | 2015-04-30 | 2.4.11 | 2016-03-17 |

| 2.5 | 2015-07-27 | 2.5.5 | 2016-03-17 |

| 2.6 | 2015-09-28 | 2.6.6 | 2016-03-17 |

| 2.7 | 2015-10-04 | 2.7.4 | 2016-03-17 |

| 2.8 | 2016-03-28 | 2.8.4 | 2016-06-06 |

| 2.9 | 2016-06-13 | 2.9.3 | 2016-08-12 |

| 2.10 | 2016-09-02 | 2.10 | 2016-09-02 |

Legend: Old version Older version, still maintained Latest version Latest preview version | |||

Design

Git's design was inspired by BitKeeper and Monotone.[26][27] Git was originally designed as a low-level version control system engine on top of which others could write front ends, such as Cogito or StGIT.[27] The core Git project has since become a complete version control system that is usable directly.[28] While strongly influenced by BitKeeper, Torvalds deliberately avoided conventional approaches, leading to a unique design.[29]

Characteristics

Git's design is a synthesis of Torvalds's experience with Linux in maintaining a large distributed development project, along with his intimate knowledge of file system performance gained from the same project and the urgent need to produce a working system in short order. These influences led to the following implementation choices:

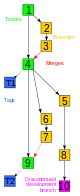

- Strong support for non-linear development

- Git supports rapid branching and merging, and includes specific tools for visualizing and navigating a non-linear development history. A core assumption in Git is that a change will be merged more often than it is written, as it is passed around various reviewers. Branches in Git are very lightweight: A branch in Git is only a reference to a single commit. With its parental commits, the full branch structure can be constructed.

- Distributed development

- Like Darcs, BitKeeper, Mercurial, SVK, Bazaar and Monotone, Git gives each developer a local copy of the entire development history, and changes are copied from one such repository to another. These changes are imported as additional development branches, and can be merged in the same way as a locally developed branch.

- Compatibility with existing systems/protocols

- Repositories can be published via HTTP, FTP, rsync (until Git 2.8.0[30]), or a Git protocol over either a plain socket, or ssh. Git also has a CVS server emulation, which enables the use of existing CVS clients and IDE plugins to access Git repositories. Subversion and svk repositories can be used directly with git-svn.

- Efficient handling of large projects

- Torvalds has described Git as being very fast and scalable,[31] and performance tests done by Mozilla[32] showed it was an order of magnitude faster than some version-control systems, and fetching version history from a locally stored repository can be one hundred times faster than fetching it from the remote server.[33]

- Cryptographic authentication of history

- The Git history is stored in such a way that the ID of a particular version (a commit in Git terms) depends upon the complete development history leading up to that commit. Once it is published, it is not possible to change the old versions without it being noticed. The structure is similar to a Merkle tree, but with additional data at the nodes as well as the leaves.[34] (Mercurial and Monotone also have this property.)

- Toolkit-based design

- Git was designed as a set of programs written in C, and a number of shell scripts that provide wrappers around those programs.[35] Although most of those scripts have since been rewritten in C for speed and portability, the design remains, and it is easy to chain the components together.[36]

- Pluggable merge strategies

- As part of its toolkit design, Git has a well-defined model of an incomplete merge, and it has multiple algorithms for completing it, culminating in telling the user that it is unable to complete the merge automatically and that manual editing is required.

- Garbage accumulates until collected

- Aborting operations or backing out changes will leave useless dangling objects in the database. These are generally a small fraction of the continuously growing history of wanted objects. Git will automatically perform garbage collection when enough loose objects have been created in the repository. Garbage collection can be called explicitly using

git gc --prune.[37] - Periodic explicit object packing

- Git stores each newly created object as a separate file. Although individually compressed, this takes a great deal of space and is inefficient. This is solved by the use of packs that store a large number of objects in a single file (or network byte stream) called packfile, delta-compressed among themselves. Packs are compressed using the heuristic that files with the same name are probably similar, but do not depend on it for correctness. A corresponding index file is created for each packfile, telling the offset of each object in the packfile. Newly created objects (newly added history) are still stored singly, and periodic repacking is required to maintain space efficiency. The process of packing the repository can be very computationally expensive. By allowing objects to exist in the repository in a loose, but quickly generated format, Git allows the expensive pack operation to be deferred until later when time does not matter (e.g. the end of the work day). Git does periodic repacking automatically but manual repacking is also possible with the git gc command. For data integrity, both packfile and its index have SHA-1 checksum inside, and also the file name of packfile contains a SHA-1 checksum. To check integrity, run the git fsck command.

Another property of Git is that it snapshots directory trees of files. The earliest systems for tracking versions of source code, SCCS and RCS, worked on individual files and emphasized the space savings to be gained from interleaved deltas (SCCS) or delta encoding (RCS) the (mostly similar) versions. Later revision control systems maintained this notion of a file having an identity across multiple revisions of a project. However, Torvalds rejected this concept.[38] Consequently, Git does not explicitly record file revision relationships at any level below the source code tree.

Implicit revision relationships have some significant consequences:

- It is slightly more expensive to examine the change history of a single file than the whole project.[39] To obtain a history of changes affecting a given file, Git must walk the global history and then determine whether each change modified that file. This method of examining history does, however, let Git produce with equal efficiency a single history showing the changes to an arbitrary set of files. For example, a subdirectory of the source tree plus an associated global header file is a very common case.

- Renames are handled implicitly rather than explicitly. A common complaint with CVS is that it uses the name of a file to identify its revision history, so moving or renaming a file is not possible without either interrupting its history, or renaming the history and thereby making the history inaccurate. Most post-CVS revision control systems solve this by giving a file a unique long-lived name (analogous to an inode number) that survives renaming. Git does not record such an identifier, and this is claimed as an advantage.[40][41] Source code files are sometimes split or merged as well as simply renamed,[42] and recording this as a simple rename would freeze an inaccurate description of what happened in the (immutable) history. Git addresses the issue by detecting renames while browsing the history of snapshots rather than recording it when making the snapshot.[43] (Briefly, given a file in revision N, a file of the same name in revision N−1 is its default ancestor. However, when there is no like-named file in revision N−1, Git searches for a file that existed only in revision N−1 and is very similar to the new file.) However, it does require more CPU-intensive work every time history is reviewed, and a number of options to adjust the heuristics. This mechanism does not always work; sometimes a file that is renamed with changes in the same commit is read as a deletion of the old file and the creation of a new file. Developers can work around this limitation by committing the rename and changes separately.

Git implements several merging strategies; a non-default can be selected at merge time:[44]

- resolve: the traditional three-way merge algorithm.

- recursive: This is the default when pulling or merging one branch, and is a variant of the three-way merge algorithm.

When there are more than one common ancestors that can be used for three-way merge, it creates a merged tree of the common ancestors and uses that as the reference tree for the three-way merge. This has been reported to result in fewer merge conflicts without causing mis-merges by tests done on actual merge commits taken from Linux 2.6 kernel development history. Additionally this can detect and handle merges involving renames.

— Linus Torvalds[45] - octopus: This is the default when merging more than two heads.

Data structures

Git's primitives are not inherently a source code management (SCM) system. Torvalds explains,[46]

In many ways you can just see git as a filesystem – it's content-addressable, and it has a notion of versioning, but I really really designed it coming at the problem from the viewpoint of a filesystem person (hey, kernels is what I do), and I actually have absolutely zero interest in creating a traditional SCM system.

From this initial design approach, Git has developed the full set of features expected of a traditional SCM,[28] with features mostly being created as needed, then refined and extended over time.

Git has two data structures: a mutable index (also called stage or cache) that caches information about the working directory and the next revision to be committed; and an immutable, append-only object database.

The object database contains four types of objects:

- A blob (binary large object) is the content of a file. Blobs have no proper file name, time stamps, or other metadata. (A blob's name internally is a hash of its content.)

- A tree object is the equivalent of a directory. It contains a list of file names, each with some type bits and a reference to a blob or tree object that is that file, symbolic link, or directory's contents. These objects are a snapshot of the source tree.

- A commit object links tree objects together into a history. It contains the name of a tree object (of the top-level source directory), a time stamp, a log message, and the names of zero or more parent commit objects.

- A tag object is a container that contains reference to another object and can hold additional meta-data related to another object. Most commonly, it is used to store a digital signature of a commit object corresponding to a particular release of the data being tracked by Git.

The index serves as connection point between the object database and the working tree.

Each object is identified by a SHA-1 hash of its contents. Git computes the hash, and uses this value for the object's name. The object is put into a directory matching the first two characters of its hash. The rest of the hash is used as the file name for that object.

Git stores each revision of a file as a unique blob. The relationships between the blobs can be found through examining the tree and commit objects. Newly added objects are stored in their entirety using zlib compression. This can consume a large amount of disk space quickly, so objects can be combined into packs, which use delta compression to save space, storing blobs as their changes relative to other blobs.

Git servers typically listen on TCP port 9418.[47]

References

Every object in the Git database which is not referred to may be cleaned up by using a garbage collection command, or automatically. An object may be referenced by another object, or an explicit reference. Git knows different types of references. The commands to create, move, and delete references vary. "git show-ref" lists all references. Some types are:

- heads: refers to an object locally

- remotes: refers to an object which exists in a remote repository

- stash: refers to an object not yet committed

- meta: e.g. a configuration in a bare repository, user rights; the refs/meta/config namespace was introduced resp gets used by Gerrit[clarification needed][48]

- tags: see above

Implementations

Git is primarily developed on Linux, although it also supports most major operating systems including BSD, Solaris, OS X, and Microsoft Windows.[49]

The first Microsoft Windows "port" of Git was primarily a Linux emulation framework that hosts the Linux version. Installing Git under Windows creates a similarly named Program Files directory containing 5,236 files in 580 directories. These include the MinGW port of the GNU Compiler Collection, Perl 5, msys2.0, itself a fork of Cygwin, a Unix-like emulation environment for Windows, and various other Windows ports or emulations of Linux utilities and libraries. Currently native Windows builds of Git are distributed as 32 and 64-bit installers.

The JGit implementation of Git is a pure Java software library, designed to be embedded in any Java application. JGit is used in the Gerrit code review tool and in EGit, a Git client for the Eclipse IDE.[50]

The Dulwich implementation of Git is a pure Python software component for Python 2.[51]

The libgit2 implementation of Git is an ANSI C software library with no other dependencies, which can be built on multiple platforms including Microsoft Windows, Linux, Mac OS X, and BSD.[52] It has bindings for many programming languages, including Ruby, Python and Haskell.[53][54][55]

JS-Git is a JavaScript implementation of a subset of Git.[56]

Git server

As Git is a distributed version control system, it can be used as a server out of the box. Dedicated Git server software helps, amongst other features, to add access control, display the contents of a Git repository via the web, and help managing multiple repositories. Remote file store and shell access: A Git repository can be cloned to a shared file system, and accessed by other persons. It can also be accessed via remote shell just by having the Git software installed and allowing a user to log in.[57]

Related article: Comparison of source code hosting facilities

Adoption

The Eclipse Foundation reported in its annual community survey that as of May 2014, Git is now the most widely used source code management tool, with 42.9% of professional software developers reporting that they use Git as their primary source control system[58] compared with 36.3% in 2013, 32% in 2012; or for Git responses excluding use of GitHub: 33.3% in 2014, 30.3% in 2013, 27.6% in 2012 and 12.8% in 2011.[59] Open source directory Black Duck Open Hub reports a similar uptake among open source projects.[60]

The UK IT jobs website itjobswatch.co.uk reports that as of late December 2014, 23.58% of UK permanent software development job openings have cited Git,[61] ahead of 16.34% for Subversion,[62] 11.58% for Microsoft Team Foundation Server,[63] 1.62% for Mercurial,[64] and 1.13% for Visual SourceSafe.[65]

Security

Git does not provide access control mechanisms, but was designed for operation with other tools that specialize in access control.[66]

On 17 December 2014, an exploit was found affecting the Windows and Mac versions of the Git client. An attacker could perform arbitrary code execution on a Windows or Mac computer with Git installed by creating a malicious Git tree (directory) named .git (a directory in Git repositories that stores all the data of the repository) in a different case (such as .GIT or .Git, needed because Git doesn't allow the all-lowercase version of .git to be created manually) with malicious files in the .git/hooks subdirectory (a folder with executable files that Git runs) on a repository that the attacker made or on a repository that the attacker can modify. If a Windows or Mac user "pulls" (downloads) a version of the repository with the malicious directory, then switches to that directory, the .git directory will be overwritten (due to the case-insensitive nature of the Windows and Mac filesystems) and the malicious executable files in .git/hooks may be run, which results in the attacker's commands being executed. An attacker could also modify the .git/config configuration file, which allows the attacker to create malicious Git aliases (aliases for Git commands or external commands) or modify existing aliases to execute malicious commands when run. The vulnerability was patched in version 2.2.1 of Git, released on 17 December 2014, and announced on the next day.[67][68]

Git version 2.6.1, released on 29 September 2015, contained a patch for a security vulnerability (CVE-2015-7545)[69] which allowed arbitrary code execution.[70] The vulnerability was exploitable if an attacker could convince a victim to clone a specific URL, as the arbitrary commands were embedded in the URL itself.[71] An attacker could use the exploit via a man-in-the-middle attack if the connection was unencrypted,[71] as they could redirect the user to a URL of their choice. Recursive clones were also vulnerable, since they allowed the controller of a repository to specify arbitrary URLs via the gitmodules file.[71]

Git uses SHA-1 hashes internally. Linus Torvalds has responded that the hash was mostly to guard against accidental corruption, and the security a cryptographically secure hash gives was just an accidental side effect, with the main security being signing elsewhere.[72][73]

See also

- GitHub

- Comparison of version control software

- Comparison of source code hosting facilities

- List of revision control software

References

- ^ "Initial revision of "git", the information manager from hell". Github. 8 April 2005. Retrieved 20 December 2015.

- ^ "Commit Graph". Github. 8 June 2016. Retrieved 19 December 2015.

- ^ "Git Source Code Mirror". Retrieved 4 November 2015.

- ^ "Git's GPL license at github.com". github.com. 18 January 2010. Retrieved 12 October 2014.

- ^ "Git's LGPL license at github.com". github.com. 20 May 2011. Retrieved 12 October 2014.

- ^ "Tech Talk: Linus Torvalds on git (at 00:01:30)". YouTube. Retrieved 20 July 2014.

- ^ Scopatz, Anthony; Huff, Kathryn D. (2015). Effective Computation in Physics. O'Reilly Media, Inc. p. 351. ISBN 9781491901595. Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- ^ a b Torvalds, Linus (7 April 2005). "Re: Kernel SCM saga." linux-kernel (Mailing list).

{{cite mailing list}}: Unknown parameter|mailinglist=ignored (|mailing-list=suggested) (help) "So I'm writing some scripts to try to track things a whole lot faster." - ^ a b Torvalds, Linus (10 June 2007). "Re: fatal: serious inflate inconsistency". git (Mailing list).

{{cite mailing list}}: Unknown parameter|mailinglist=ignored (|mailing-list=suggested) (help) A brief description of Git's data integrity design goals. - ^ a b c d e Linus Torvalds (3 May 2007). Google tech talk: Linus Torvalds on git. Event occurs at 02:30. Retrieved 16 May 2007.

- ^ "A Short History of Git". Pro Git (2nd ed.). Apress. 2014. Retrieved 26 December 2015.

- ^ Chacon, Scott (24 December 2014). Pro Git (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Apress. pp. 29–30. ISBN 978-1-4842-0077-3.

- ^ BitKeeper and Linux: The end of the road? | linux.com

- ^ McAllister, Neil (2 May 2005). "Linus Torvalds' BitKeeper blunder". InfoWorld. IDG. Retrieved 8 September 2015.

- ^ "GitFaq: Why the 'Git' name?". Git.or.cz. Retrieved 14 July 2012.

- ^ "After controversy, Torvalds begins work on 'git'". PC World. 14 July 2012.

Torvalds seemed aware that his decision to drop BitKeeper would also be controversial. When asked why he called the new software, "git", British slang meaning "a rotten person", he said. "I'm an egotistical bastard, so I name all my projects after myself. First Linux, now git"

- ^ "git(1) Manual Page". Retrieved 21 July 2012.

- ^ "Initial revision of "git", the information manager from hell · git/git@e83c516". GitHub. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- ^ a b Torvalds, Linus (27 February 2007). "Re: Trivia: When did git self-host?". git (Mailing list).

{{cite mailing list}}: Unknown parameter|mailinglist=ignored (|mailing-list=suggested) (help) - ^ Torvalds, Linus (6 April 2005). "Kernel SCM saga." linux-kernel (Mailing list).

{{cite mailing list}}: Unknown parameter|mailinglist=ignored (|mailing-list=suggested) (help) - ^ Torvalds, Linus (17 April 2005). "First ever real kernel git merge!". git (Mailing list).

{{cite mailing list}}: Unknown parameter|mailinglist=ignored (|mailing-list=suggested) (help) - ^ Mackall, Matt (29 April 2005). "Mercurial 0.4b vs git patchbomb benchmark". git (Mailing list).

{{cite mailing list}}: Unknown parameter|mailinglist=ignored (|mailing-list=suggested) (help) - ^ Torvalds, Linus (17 June 2005). "Linux 2.6.12". git-commits-head (Mailing list).

{{cite mailing list}}: Unknown parameter|mailinglist=ignored (|mailing-list=suggested) (help) - ^ Torvalds, Linus (27 July 2005). "Meet the new maintainer..." git (Mailing list).

{{cite mailing list}}: Unknown parameter|mailinglist=ignored (|mailing-list=suggested) (help) - ^ Hamano, Junio C. (21 December 2005). "Announce: Git 1.0.0". git (Mailing list).

{{cite mailing list}}: Unknown parameter|mailinglist=ignored (|mailing-list=suggested) (help) - ^ Torvalds, Linus (5 May 2006). "Re: [ANNOUNCE] Git wiki". linux-kernel (Mailing list).

{{cite mailing list}}: Unknown parameter|mailinglist=ignored (|mailing-list=suggested) (help) "Some historical background" on Git's predecessors - ^ a b Torvalds, Linus (8 April 2005). "Re: Kernel SCM saga". linux-kernel (Mailing list). Retrieved 20 February 2008.

{{cite mailing list}}: Unknown parameter|mailinglist=ignored (|mailing-list=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Torvalds, Linus (23 March 2006). "Re: Errors GITtifying GCC and Binutils". git (Mailing list).

{{cite mailing list}}: Unknown parameter|mailinglist=ignored (|mailing-list=suggested) (help) - ^ Torvalds, Linus (20 October 2006). "Re: VCS comparison table". git (Mailing list).

{{cite mailing list}}: Unknown parameter|mailinglist=ignored (|mailing-list=suggested) (help) A discussion of Git vs. BitKeeper - ^ Git 2.8.0 Release Notes "Documentation/RelNotes/2.8.0.txt". 29 March 2016.

- ^ Torvalds, Linus (19 October 2006). "Re: VCS comparison table". git (Mailing list).

{{cite mailing list}}: Unknown parameter|mailinglist=ignored (|mailing-list=suggested) (help) - ^ Jst's Blog on Mozillazine "bzr/hg/git performance". Archived from the original on 29 May 2010. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Dreier, Roland (13 November 2006). "Oh what a relief it is"., observing that "git log" is 100x faster than "svn log" because the latter has to contact a remote server.

- ^ "Trust". Git Concepts. Git User's Manual. 18 October 2006.

- ^ Torvalds, Linus. "Re: VCS comparison table". git (Mailing list). Retrieved 10 April 2009.

{{cite mailing list}}: Unknown parameter|mailinglist=ignored (|mailing-list=suggested) (help), describing Git's script-oriented design - ^ iabervon (22 December 2005). "Git rocks!"., praising Git's scriptability

- ^ "Git User's Manual". 5 August 2007.

- ^ Torvalds, Linus (10 April 2005). "Re: more git updates." linux-kernel (Mailing list).

{{cite mailing list}}: Unknown parameter|mailinglist=ignored (|mailing-list=suggested) (help) - ^ Haible, Bruno (11 February 2007). "how to speed up "git log"?". git (Mailing list).

{{cite mailing list}}: Unknown parameter|mailinglist=ignored (|mailing-list=suggested) (help) - ^ Torvalds, Linus (1 March 2006). "Re: impure renames / history tracking". git (Mailing list).

{{cite mailing list}}: Unknown parameter|mailinglist=ignored (|mailing-list=suggested) (help) - ^ Hamano, Junio C. (24 March 2006). "Re: Errors GITtifying GCC and Binutils". git (Mailing list).

{{cite mailing list}}: Unknown parameter|mailinglist=ignored (|mailing-list=suggested) (help) - ^ Hamano, Junio C. (23 March 2006). "Re: Errors GITtifying GCC and Binutils". git (Mailing list).

{{cite mailing list}}: Unknown parameter|mailinglist=ignored (|mailing-list=suggested) (help) - ^ Torvalds, Linus (28 November 2006). "Re: git and bzr". git (Mailing list).

{{cite mailing list}}: Unknown parameter|mailinglist=ignored (|mailing-list=suggested) (help), on usinggit-blameto show code moved between source files - ^ Torvalds, Linus (18 July 2007). "git-merge(1)".

- ^ Torvalds, Linus (18 July 2007). "CrissCrossMerge".

- ^ Torvalds, Linus (10 April 2005). "Re: more git updates..." linux-kernel (Mailing list).

{{cite mailing list}}: Unknown parameter|mailinglist=ignored (|mailing-list=suggested) (help) - ^ "1.4 Getting Started – Installing Git". git-scm.com. Retrieved 1 November 2013.

- ^ Gerrit Code Review – Project Configuration File Format

- ^ "downloads". Retrieved 14 May 2012.

- ^ "JGit". Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- ^ "Dulwich". Retrieved 27 August 2012.

- ^ "libgit2". Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- ^ "rugged". Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- ^ "pygit2". Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- ^ "hlibgit2". Retrieved 30 April 2013.

- ^ https://github.com/creationix/js-git "js-git: a JavaScript implementation of Git." Retrieved 13 August 2013.

- ^ 4.4 Git on the Server – Setting Up the Server, Pro Git.

- ^ "Eclipse Community Survey 2014 results | Ian Skerrett". Ianskerrett.wordpress.com. 23 June 2014. Retrieved 23 June 2014.

- ^ "Results of Eclipse Community Survey 2012".

- ^ "Compare Repositories – Open Hub".

- ^ "Git (software) Jobs, Average Salary for Git Distributed Version Control System Skills". Itjobswatch.co.uk. Retrieved 31 December 2014.

- ^ "Subversion Jobs, Average Salary for Apache Subversion (SVN) Skills". Itjobswatch.co.uk. Retrieved 31 December 2014.

- ^ "Team Foundation Server Jobs, Average Salary for Microsoft Team Foundation Server (TFS) Skills". Itjobswatch.co.uk. Retrieved 31 December 2014.

- ^ "Mercurial Jobs, Average Salary for Mercurial Skills". Itjobswatch.co.uk. Retrieved 31 December 2014.

- ^ "VSS/SourceSafe Jobs, Average Salary for Microsoft Visual SourceSafe (VSS) Skills". Itjobswatch.co.uk. Retrieved 31 December 2014.

- ^ https://wincent.com/wiki/git_repository_access_control

- ^ Pettersen, Tim (20 December 2014). "Securing your Git server against CVE-2014-9390". Retrieved 22 December 2014.

- ^ Hamano, J. C. (18 December 2014). "[ANNOUNCE] Git v2.2.1 (and updates to older maintenance tracks)". Newsgroup: gmane.linux.kernel. Retrieved 22 December 2014. [dead link]

- ^ "CVE-2015-7545". 15 December 2015. Retrieved 26 December 2015.

- ^ "Git 2.6.1". 29 September 2015. Retrieved 26 December 2015.

- ^ a b c Blake Burkhart; et al. (5 October 2015). "Re: CVE Request: git". Retrieved 26 December 2015.

- ^ "hash - How safe are signed git tags? Only as safe as SHA-1 or somehow safer?". Information Security Stack Exchange. 22 September 2014.

- ^ "Why does Git use a cryptographic hash function?". Stack Overflow. 1 March 2015.