Human rights in the Soviet Union: Difference between revisions

Explain why you have to make a revert on the talk page before reverting to an old version of the section. See talk. |

|||

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

According to [[Universal Declaration of Human Rights]], human rights are the "basic [[right]]s and [[freedom (political)|freedoms]] to which all humans are entitled."<ref>Houghton Miffin Company (2006)</ref>, including the right to [[life]] and [[liberty]], [[freedom of speech|freedom of expression]], and [[equality before the law]]; and social, cultural and economic rights, including the right to participate in [[culture]], the [[right to food]], the [[right to work]], and the right to [[education]]. |

According to [[Universal Declaration of Human Rights]], human rights are the "basic [[right]]s and [[freedom (political)|freedoms]] to which all humans are entitled."<ref>Houghton Miffin Company (2006)</ref>, including the right to [[life]] and [[liberty]], [[freedom of speech|freedom of expression]], and [[equality before the law]]; and social, cultural and economic rights, including the right to participate in [[culture]], the [[right to food]], the [[right to work]], and the right to [[education]]. |

||

However the Soviet conception of human rights was very different from conceptions prevalent in the West. According to Western legal theory, "it is the individual who is the beneficiary of human rights which are to be asserted ''against'' the government", whereas Soviet law claimed the opposite <ref>Lambelet, Doriane. "The Contradiction Between Soviet and American Human Rights Doctrine: Reconciliation Through Perestroika and Pragmatism." 7 ''Boston University International Law Journal''. 1989. p. 61-62.</ref>. The [[Soviet state]] was considered as the source of [[human rights]]<ref name=shiman>{{cite book | last = Shiman | first = David | title = Economic and Social Justice: A Human Rights Perspective | publisher = Amnesty International | year= 1999 | url = http://www1.umn.edu/humanrts/edumat/hreduseries/tb1b/Section1/tb1-2.htm | isbn = 0967533406}}</ref>. Therefore, Soviet legal system regarded [[law]] as an arm of politics and courts as agencies of the government <ref name="Pipes"/>. Extensive [[Extrajudicial punishment|extra-judiciary powers]] were given to the [[Chronology of Soviet secret police agencies|Soviet secret police agencies]]. The regime abolished Western [[rule of law]], [[civil liberties]], [[Criminal justice|protection of law]] and [[Property rights|guarantees of property]].<ref> [[Richard Pipes]] (2001) ''Communism'' Weidenfled and Nicoloson. ISBN 0-297-64688-5 </ref><ref> [[Richard Pipes]] (1994) ''Russia Under the Bolshevik Regime''. Vintage. ISBN 0-679-76184-5., pages 401–403. </ref>. According to [[Vladimir Lenin]], the purpose of [[People's court (Soviet Union)|socialist courts]] was "not to eliminate [[Great Terror|terror]] ... but to substantiate it and legitimize in principle" <ref name="Pipes"/>. |

|||

Crime was determined not as the infraction of law, but as any action which could threaten the Soviet state and society. For example, [[Speculation|a desire to make a profit]] could be interpreted as a [[Counter-revolutionary|counter-revolutionary activity]] punishable by death.<ref name="Pipes"/> [[Dekulakization|The liquidation and deportation of millions peasants in 1928–31]] was carried out within the terms of Soviet Civil Code.<ref name="Pipes"> [[Richard Pipes]] ''Russia Under the Bolshevik Regime'', Vintage books, Random House Inc., New York, 1995, ISBN 0-394-50242-6, pages 402–403 </ref> Some Soviet legal scholars even asserted that "criminal repression" may be applied in the absence of guilt."<ref name="Pipes"/>. [[Martin Latsis]], chief of the Ukrainian [[Cheka]] explained: "Do not look in the file of incriminating evidence to see whether or not the accused rose up against the Soviets with arms or words. Ask him instead to which [[social class|class]] he belongs, what is his background, his [[education]], his [[profession]]. These are the questions that will determine the fate of the accused. That is the meaning and essence of the [[Red Terror]]."<ref name="State"> [[Yevgenia Albats]] and Catherine A. Fitzpatrick. ''The State Within a State: The KGB and Its Hold on Russia – Past, Present, and Future'', 1994. ISBN 0-374-52738-5.</ref> |

|||

It was argued in the West that the Soviets rejected the Western concept of the "[[rule of law]]" as the belief that [[law]] should be more than just the instrument of [[politics]].<ref name="Lambelet"/> However, article 4 in the Soviet Constitution states that everyone has to observe Soviet laws, including state officials and organizations.{{Citation needed|date=October 2009}} |

|||

The purpose of [[Show trial|public trials]] was "not to demonstrate the existence or absence of a crime – that was predetermined by the appropriate [[CPSU|party authorities]] – but to provide yet another forum for [[Soviet propaganda|political agitation and propaganda]] for the instruction of the citizenry (see [[Moscow Trials]] for example). Defense lawyers, who had to be [[CPSU|party members]], were required to take their client's guilt for granted..."<ref name="Pipes"/> |

|||

==Freedom of political expression== |

==Freedom of political expression== |

||

Revision as of 14:49, 5 February 2010

The Soviet Union was a single-party state where the Communist Party ruled the country.[citation needed] Independent political activities were not tolerated, including the involvement of people with free labour unions, private corporations, non-sanctioned churches or opposition political parties. The government made use of secret police, restricted freedom of speech, and engaged in mass surveillance. These actions have been criticised as human rights violations.

Soviet concept of human rights and legal system

According to Universal Declaration of Human Rights, human rights are the "basic rights and freedoms to which all humans are entitled."[1], including the right to life and liberty, freedom of expression, and equality before the law; and social, cultural and economic rights, including the right to participate in culture, the right to food, the right to work, and the right to education.

However the Soviet conception of human rights was very different from conceptions prevalent in the West. According to Western legal theory, "it is the individual who is the beneficiary of human rights which are to be asserted against the government", whereas Soviet law claimed the opposite [2]. The Soviet state was considered as the source of human rights[3]. Therefore, Soviet legal system regarded law as an arm of politics and courts as agencies of the government [4]. Extensive extra-judiciary powers were given to the Soviet secret police agencies. The regime abolished Western rule of law, civil liberties, protection of law and guarantees of property.[5][6]. According to Vladimir Lenin, the purpose of socialist courts was "not to eliminate terror ... but to substantiate it and legitimize in principle" [4].

Crime was determined not as the infraction of law, but as any action which could threaten the Soviet state and society. For example, a desire to make a profit could be interpreted as a counter-revolutionary activity punishable by death.[4] The liquidation and deportation of millions peasants in 1928–31 was carried out within the terms of Soviet Civil Code.[4] Some Soviet legal scholars even asserted that "criminal repression" may be applied in the absence of guilt."[4]. Martin Latsis, chief of the Ukrainian Cheka explained: "Do not look in the file of incriminating evidence to see whether or not the accused rose up against the Soviets with arms or words. Ask him instead to which class he belongs, what is his background, his education, his profession. These are the questions that will determine the fate of the accused. That is the meaning and essence of the Red Terror."[7]

The purpose of public trials was "not to demonstrate the existence or absence of a crime – that was predetermined by the appropriate party authorities – but to provide yet another forum for political agitation and propaganda for the instruction of the citizenry (see Moscow Trials for example). Defense lawyers, who had to be party members, were required to take their client's guilt for granted..."[4]

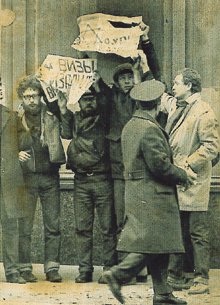

Freedom of political expression

The political repressions were practiced by the Soviet secret police services Cheka, OGPU and NKVD.[8] An extensive network of civilian informants – either volunteers, or those forcibly recruited – was used to collect intelligence for the government and report cases of suspected dissent.[9]

Soviet political repression was a de facto and de jure system of prosecution of people who were or perceived to be enemies of the Soviet system.[citation needed] Its theoretical basis were the theory of Marxism about the class struggle. The term "repression", "terror", and other strong words were official working terms, since the dictatorship of the proletariat was supposed to suppress the resistance of other social classes which Marxism considered antagonistic to the class of proletariat. The legal basis of the repression was formalized into the Article 58 in the code of RSFSR and similar articles for other Soviet republics. Aggravation of class struggle under socialism was proclaimed during the Stalinist terror.

Freedom of literary and scientific expression

Censorship in the Soviet Union was pervasive and strictly enforced.[10] This gave rise to Samizdat, a clandestine copying and distribution of government-suppressed literature. Art, literature, education, and science were placed under a strict ideological scrutiny, since they were supposed to serve the interests of the victorious proletariat. Socialist realism is an example of such teleologically-oriented art that promoted socialism and communism. All humanities and social sciences were tested for strict accordance with historical materialism.

All natural sciences have to be founded on the philosophical base of dialectical materialism. Many scientific disciplines, such as genetics, cybernetics, and comparative linguistics, were suppressed in the Soviet Union during some periods, condemned as "bourgeois pseudoscience". At one point Lysenkoism, which many consider a pseudoscience, was favored in agriculture and biology. In the 1930s and 1940s, many prominent scientists were declared to be "wrecklers" or enemy of the people and imprisoned. Some scientists worked as prisoners in "Sharashkas", i.e. research and development laboratories within the Gulag labor camp system.

Every large enterprise or institution of the Soviet Union had First Department run by KGB people responsible for secrecy and political security of the workplace.[citation needed]

According to Soviet Criminal Code, agitation or propaganda carried on for the purpose of weakening Soviet authority, circulating materials or literature that defamed the Soviet State and social system were punishable by imprisonment for a term of 2–5 years and for a second offense, punishable for a term of 3–10 years.[11]

Right to vote

According to communist ideologists, the Soviet political system was a true democracy, where workers' councils called "soviets" represented the will of the working class. In particular, the Soviet Constitution of 1936 guaranteed direct universal suffrage with the secret ballot. However all candidates had been selected by Communist party organizations, at least before the June 1987 elections. Historian Robert Conquest described this system as "a set of phantom institutions and arrangements which put a human face on the hideous realities: a model constitution adopted in a worst period of terror and guaranteeing human rights, elections in which there was only one candidate, and in which 99 percent voted; a parliament at which no hand was ever raised in opposition or abstention."[12]

Economic rights

Personal property was allowed, with certain limitations. All real property belonged to the state and society.[citation needed] Unauthorized possession of foreign currency was forbidden and prosecuted as criminal offense. Within the wage labour economy, health, education and nutrition were guaranteed in most circumstances after 1930 through the provision of full employment and economic welfare structures implemented in the workplace. Outside of the wage labour economy, in subsistence agriculture, and for indigenous peoples, economic rights were not guaranteed, and significant human rights abuses occurred, particularly in terms of preventable famines to 1949.[citation needed]

Freedoms of assembly and association

Freedoms of assembly and association were limited.[citation needed] Workers were not allowed to organize free trade unions. All existing trade unions were organized and controlled by the state.[13] All political youth organizations, such as Pioneer movement and Komsomol served to enforce the policies of the Communist Party. Participation in non-authorized political organizations could result in imprisonment or even the death penalty.[11]

Freedom of religion

The Soviet Union promoted atheism. The Soviet Union was the first state to have as an ideological objective the elimination of religion.[citation needed] Toward that end, the Communist regime confiscated church property, ridiculed religion, harassed believers, and propagated atheism in the schools. Actions toward particular religions, however, were determined by State interests, and most organized religions were never outlawed.

Some actions against Orthodox priests and believers along with execution included torture, being sent to prison camps, labour camps or mental hospitals.[14][15][16][17] Many Orthodox (along with peoples of other faiths) were also subjected to psychological punishment or torture and mind controlexperimentation in order to force them give up their religious convictions (see Punitive psychiatry in the Soviet Union).[15][16][18][19]

Practicing Orthodox Christians were restricted from prominent careers and membership in communist organizations (the party, the Komsomol). Anti-religious propaganda was openly sponsored and encouraged by the government, which the Church was not given an opportunity to publicly respond to. Seminaries were closed down, and the church was restricted from using the press. Atheism was propagated through schools, communist organizations, and the media. Organizations such as the Society of the Godless were created.

Freedom of movement

Emigration and any travel abroad were not allowed without an explicit permission from the government. People who were not allowed to leave the country and campaigned for their right to leave in 1970s were known as "refuseniks". According to the Soviet Criminal Code, a refusal to return from abroad was Treason punishable by imprisonment for a term of 10–15 years or death with confiscation of property.[11]

Passport system in the Soviet Union restricted migration of citizens within the country through "propiska" (residential permit/registration system) and use of internal passports. For a long period of the Soviet history peasants did not have internal passports and could not move into towns without permission. Many former inmates received "wolf ticket" and were only allowed to live at least 101 km away from city borders. Travel to closed cities and to the regions near USSR state borders was strongly restricted. An attempt to illegally escape abroad was punishable by imprisonment for 1–3 years.[11]

Human rights movement in the USSR

- Action Group for the Defence of Civil rights in the USSR was founded in May 1969. The organization petitioned on behalf of the victims of Soviet repressions. It was dissolved after the arrest and trial of its leading member Peter Yakir.

- In November 1970 the Moscow Human Rights Committee was founded by Andrei Sakharov and his colleagues to publicize Soviet violations of human rights.

- USSR's section of Amnesty International was founded on October 6 1973 by 11 Moscow intellectuals and was registered in September 1974 by the Amnesty international Secretariat in London.

- The Moscow Helsinki Group was founded in 1976 to monitor the Soviet Union's compliance with the Helsinki Final Act of 1975 that included clauses calling for the recognition of universal human rights.

- The Ukrainian Helsinki Group was founded in November 1976 to monitor human rights in Ukraine.[20] The group was active until 1981 when all members were jailed.

References

- ^ Houghton Miffin Company (2006)

- ^ Lambelet, Doriane. "The Contradiction Between Soviet and American Human Rights Doctrine: Reconciliation Through Perestroika and Pragmatism." 7 Boston University International Law Journal. 1989. p. 61-62.

- ^ Shiman, David (1999). Economic and Social Justice: A Human Rights Perspective. Amnesty International. ISBN 0967533406.

- ^ a b c d e f Richard Pipes Russia Under the Bolshevik Regime, Vintage books, Random House Inc., New York, 1995, ISBN 0-394-50242-6, pages 402–403

- ^ Richard Pipes (2001) Communism Weidenfled and Nicoloson. ISBN 0-297-64688-5

- ^ Richard Pipes (1994) Russia Under the Bolshevik Regime. Vintage. ISBN 0-679-76184-5., pages 401–403.

- ^ Yevgenia Albats and Catherine A. Fitzpatrick. The State Within a State: The KGB and Its Hold on Russia – Past, Present, and Future, 1994. ISBN 0-374-52738-5.

- ^ Anton Antonov-Ovseenko Beria (Russian) Moscow, AST, 1999. Russian text online

- ^ Koehler, John O. Stasi: The Untold Story of the East German Secret Police. Westview Press. 2000. ISBN 0-8133-3744-5

- ^ A Country Study: Soviet Union (Former). Chapter 9 - Mass Media and the Arts. The Library of Congress. Country Studies

- ^ a b c d Biographical Dictionary of Dissidents in the Soviet Union, 1956-1975 By S. P. de Boer, E. J. Driessen, H. L. Verhaar; ISBN 9024725380; p. 652

- ^ Robert Conquest Reflections on a Ravaged Century (2000) ISBN 0-393-04818-7, page 97

- ^ A Country Study: Soviet Union (Former). Chapter 5. Trade Unions. The Library of Congress. Country Studies. 2005.

- ^ Father Arseny 1893-1973 Priest, Prisoner, Spiritual Father. Introduction pg. vi - 1. St Vladimir's Seminary Press ISBN 0-88141-180-9

- ^ a b L.Alexeeva, History of dissident movement in the USSR, in Russian

- ^ a b A.Ginzbourg, "Only one year", "Index" Magazine, in Russian

- ^ The Washingotn Post Anti-Communist Priest Gheorghe Calciu-Dumitreasa By Patricia Sullivan Washington Post Staff Writer Sunday, November 26, 2006; Page C09 http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2006/11/25/AR2006112500783.html

- ^ http://litek.ws/k0nsl/detox/anti-humans.htm Dumitru Bacu, The Anti-Humans. Student Re-Education in Romanian Prisons], Soldiers of the Cross, Englewood, Colorado, 1971. Originally written in Romanian as Piteşti, Centru de Reeducare Studenţească, Madrid, 1963

- ^ Adrian Cioroianu, Pe umerii lui Marx. O introducere în istoria comunismului românesc ("On the Shoulders of Marx. An Incursion into the History of Romanian Communism"), Editura Curtea Veche, Bucharest, 2005

- ^ Museum of dissident movement in Ukraine

Bibliography

- Applebaum, Anne (2003) Gulag: A History. Broadway Books. ISBN 0-7679-0056-1

- Conquest, Robert (1991) The Great Terror: A Reassessment. Oxford University Press ISBN 0-19-507132-8.

- Conquest, Robert (1986) The Harvest of Sorrow: Soviet Collectivization and the Terror-Famine. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-505180-7.

- Courtois, Stephane; Werth, Nicolas; Panne, Jean-Louis; Paczkowski, Andrzej; Bartosek, Karel; Margolin, Jean-Louis & Kramer, Mark (1999). The Black Book of Communism: Crimes, Terror, Repression. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-07608-7.

- Khlevniuk, Oleg & Kozlov, Vladimir (2004) The History of the Gulag : From Collectivization to the Great Terror (Annals of Communism Series) Yale University Pres. ISBN 0-300-09284-9.

- Pipes, Richard (2001) Communism Weidenfled and Nicoloson. ISBN 0-297-64688-5

- Pipes, Richard (1994) Russia Under the Bolshevik Regime. Vintage. ISBN 0-679-76184-5.

- Rummel, R.J. (1996) Lethal Politics: Soviet Genocide and Mass Murder Since 1917. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 1-56000-887-3.

- Yakovlev, Alexander (2004). A Century of Violence in Soviet Russia. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-10322-0.

External links

- Museum of Communism

- How many did the Communist regimes murder?

- The Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation

- Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (2006) Res. 1481 Need for international condemnation of crimes of totalitarian communist regimes

- Crimes of Soviet Communists — Wide collection of sources and links

- Chekists in Cassocks: The Orthodox Church and the KGB - by Keith Armes

- The battle for the Russian Orthodox Church - by Vladimir Moss

- The Betrayal of the Church - by Edmund W. Robb and Julia Robb, 1986

See also

- Soviet democracy

- Human rights in Russia

- Stalinism

- Totalitarianism

- Criticisms of Communist party rule

For other articles on the topic see

- Category:Political repression in the Soviet Union

- Category:Victims of Soviet repressions

- Category:Gulag

- Category:Forced migration in the Soviet Union

- Category:Law enforcement in the Soviet Union

- Category:NKVD

- Category:Soviet phraseology

- Category:Rebellions in Russia

- Category:Moscow Helsinki Watch Group

- Category:Soviet dissidents

- Category:Sharashka inmates

- Category:Prisons in Russia