Scotch-Irish Americans

This includes references to census interpretation that relies excessively on references to primary sources. (August 2008) |

This article possibly contains original research. (August 2008) |

| |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| Southern United States, Western United States, Appalachia | |

| Languages | |

| American English, especially Southern Appalachian and South Midland or Highland Southern dialects of Southern American English | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Protestant (Dissenter), Presbyterian, Baptist | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| British Americans (Scottish Americans, English Americans, Welsh Americans), Irish Americans Ulster Scots, Irish, Scottish, English |

Scotch-Irish (the historically common term in North America) or Scots-Irish refers to inhabitants of the United States and, by some, of Canada who are of Ulster Scottish descent. The term may be qualified with American (or Canadian) as in "Scotch-Irish American" or "American of Scots-Irish ancestry". Today, people in the British Isles of the same ethnicity or ancestry usually call themselves "Ulster Scots", with the term "Scotch-Irish" seen as terminology only used in North America.

The term "Scotch-Irish" is an Americanism, almost unknown in Britain and Ireland, and refers to Irish Protestant immigrants from Ulster to America during the 1700s. An estimated 200,000 or more Scotch-Irish migrated to America in the 18th century.[2] The majority of these immigrants were descended from Scottish and English families who had been transplanted to Ireland during the Plantation of Ulster in the 1600s.[3]

The term "Scotch-Irish" has led to confusion even among descendants of the Scotch-Irish themselves: some taking it to mean a mixture of Scottish and Irish ethnicities, and others thinking it refers to Irish immigrants to Scotland. The term is also misleading because some of the Scotch-Irish had little or no Scottish ancestry at all, as Protestant families had also been transplanted to Ulster from northern England, Wales and the London area, and some from Flanders, the German Palatinate, and France (such as the French Huguenot ancestors of Davy Crockett). However, the large Scottish element in the Plantation of Ulster gave the Ulster Protestant settlements a Scottish character, and when the Ulster immigrants began to arrive in America they were collectively given the name "Scotch-Irish".[4]

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, 5.3 million Americans claim Scotch-Irish ancestry.[5] This figure does not include the approximately 36 million Americans reporting Irish ancestry, who are counted separately.

History

Because of the close proximity of the islands of Britain and Ireland, migrations in both directions had been occurring since Ireland was first settled after the retreat of the ice sheets. Gaels from Ireland colonised current South-West Scotland as part of the Kingdom of Dál Riata, eventually replacing the native Pictish culture throughout Scotland. These Gaels had previously been named Scoti by the Romans, and eventually the name was applied to the entire Kingdom of Scotland. The Scottish crown eventually became unified with the Kingdom of England, forming the Kingdom of Great Britain. During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries (see History of Scotland), beginning about 1615, a systematic plantation of mostly Lowland Scots settlers to Ireland was undertaken. Many settlers were hardscrabble, subsistence farmers barely able to support their families. In the early years of the Plantation, the majority of the settlers were Lowland and Border Scots seeking a better life. The Plantation was seen as a way to eliminate the problem of the Border Reivers, raiders and cattle-thieves who were causing instability along the Scottish-English frontier, and who were a potential problem for James VI of Scotland, who had recently also become King of England. Transporting reiver families to Ireland would bring peace to the Anglo-Scot border country, and also provide fighting men who could suppress the native Irish. Many of the early settlers came from the border areas of both England and Scotland.

The first major influx of Scots into Ulster came during the settlement of east Down onto land cleared of native Irish. This started in May 1606 and was followed in 1610 by the arrival of many more Scots as part of the Plantation of Ulster. The Scottish population in Ulster was further augmented during the subsequent Irish Confederate Wars. The first of the Stuart Kingdoms to collapse into civil war was Ireland, where, prompted in part by the anti-Catholic rhetoric of the Covenanters, Irish Catholics launched a rebellion in October. In reaction to the proposal by Charles I and Thomas Wentworth to raise an army manned by Irish Catholics to put down the Covenanter movement in Scotland, the Parliament of Scotland had threatened to invade Ireland in order to achieve "the extirpation of Popery out of Ireland" (according to the interpretation of Richard Bellings, a leading Irish politician of the time). The fear this caused in Ireland unleashed a wave of massacres, mostly in Ulster, against Protestant English and Scottish settlers once the rebellion had broken out. All sides displayed extreme cruelty in this phase of the war. Around 4000 settlers were massacred and a further 12,000 may have died of privation after being driven from their homes.[6][7] In one notorious incident, the Protestant inhabitants of Portadown were taken captive and then massacred on the bridge in the town.[8] The settlers responded in kind, as did the British-controlled government in Dublin, with attacks on the Irish civilian population. Massacres of native civilians occurred at Rathlin Island and elsewhere.[9] In early 1642, the Covenanters sent an army to Ulster to defend the Scottish settlers there from the Irish rebels who had attacked them after the outbreak of the rebellion. The original intention of the Scottish army was to re-conquer Ireland, but due to logistical and supply problems, it was never in a position to advance far beyond its base in eastern Ulster. The Covenanter force remained in Ireland until the end of the civil wars but was confined to its garrison around Carrickfergus after its defeat by the native Ulster Army at the Battle of Benburb in 1646. After the war was over, many of the soldiers settled permanently in Ulster. Another major influx of Scots into northern Ireland occurred in the 1690s, when tens of thousands of people fled a famine in Scotland to come to Ulster.

During the course of the 17th century, the number of settlers belonging to Calvinist dissenting sects, including Scottish and Northumbrian Presbyterians, English Baptists, French and Flemish Huguenots, and German Palatines, became the majority among the Protestant settlers in the province of Ulster. However, the Presbyterians and other dissenters, along with Catholics, were not members of the established church and were legally disadvantaged by the Penal Laws, which gave full rights only to members of the Church of England/Church of Ireland, who were often absentee landlords and the descendants of English title-holding settlers. For this reason, up until the 19th century, and despite their common fear of the dispossessed Catholic native Irish, there was considerable disharmony between the Presbyterians and the Protestant Ascendancy in Ulster. As a result of this many Ulster-Scots, along with Catholic native Irish, ignored religious differences to join the United Irishmen and participate in the Irish Rebellion of 1798, in support of egalitarian and republican goals.

Just a few generations after arriving in Ulster, considerable numbers of Ulster-Scots emigrated to the North American colonies of Great Britain throughout the 18th century (between 1717 and 1770 alone, about 250,000 settled in what would become the United States).[10] According to Kerby Miller, Emigrants and Exiles: Ireland and the Irish Exodus to North America (1988), Protestants were one-third the population of Ireland, but three-quarters of all emigrants leaving from 1700 to 1776; 70% of these Protestants were Presbyterians. Other factors contributing to the mass exodus of Ulster Scots to America during the 18th century were a series of droughts and rising rents imposed by often absentee English and/or Anglo-Irish landlords.

Author (and U.S. Senator) Jim Webb puts forth a thesis in his book Born Fighting to suggest that the character traits he ascribes to the Scotch-Irish such as loyalty to kin, extreme mistrust of governmental authority and legal strictures, and a propensity to bear arms and to use them, helped shape the American identity.

Scotch-Irish Americans

Scholarly estimate is that over 200,000 Scotch-Irish migrated to the Americas between 1717 and 1775.[11] As a late arriving group, they found that land in the coastal areas of the English colonies was either already owned or too expensive, so they quickly left for the hill country where land could be had cheaply. Here they lived on the frontiers of America. Early frontier life was extremely challenging, but poverty and hardship were familiar to them. The term "hillbilly" has often been applied disparagingly to their descendants in the mountains, carrying connotations of poverty, backwardness and violence; this word probably having its origins in Scotland and Ireland.

The first trickle of Scotch-Irish settlers arrived in New England. Valued for their fighting prowess as well as their Protestant dogma, they were invited by Cotton Mather and other leaders to come over to help settle and secure the frontier. In this capacity, many of the first permanent settlements in Maine and New Hampshire, especially after 1718, were Scotch-Irish and many place names as well as the character of Northern New Englanders reflect this fact. The Scotch-Irish brought the potato with them from Ireland. In Maine it became a staple crop as well as an economic base.[12]

From 1717 to the next thirty or so years, the primary points of entry for the Ulster immigrants were Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and New Castle, Delaware. The Scotch-Irish radiated westward across the Alleghenies, as well as into Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Kentucky, and Tennessee.[13] The early immigrants settled heavily in Chester and Lancaster Counties in Pennsylvania, but as these areas became populated later immigrants continued west into the Alleghenies and beyond to the Pittsburgh area, while the majority turned south as land was opened for settlement in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia. These immigrants followed the Great Wagon Road from Lancaster, through Gettysburg, and down through Staunton, Virginia, to Big Lick (now Roanoke), Virginia. Here the pathway split, with the Wilderness Road taking settlers west into Tennessee and Kentucky, while the main road continued south into the Carolinas.[14]

The Scotch-Irish were generally ardent supporters of American Independence from Britain in the 1770s. "In Pennsylvania, Virginia, and one section of the Carolinas", support of the Scotch-Irish for the revolution was "practically unanimous", claims James Leyburn, in The Scotch-Irish. He cites contemporary sources as evidence of overwhelming support among the Scotch-Irish for the revolution, and quotes a Hessian officer who said, "Call this war by whatever name you may, only call it not an American rebellion; it is nothing more or less than a Scotch Irish Presbyterian rebellion."[15] A British major general testified to the House of Commons that "half the rebel Continental Army were from Ireland".[16] Mecklenburg County, North Carolina, with its large Scotch-Irish population, was to make the first declaration for independence from Britain in the famous Mecklenburg Declaration of 1775. British loyalism was only seen among the Scotch-Irish of the Carolina piedmont, which caused the Continental Congress to send two Presbyterian ministers to the area in 1775 in an effort to win support for the patriot cause. The Scotch-Irish "Overmountain Men" of Virginia and North Carolina formed the patriot army who won the Battle of Kings Mountain in 1780, which caused the British to abandon their southern campaign, and "marked the turning point of the American Revolution".[17]

In the 1790s, the new American government assumed the debts the individual states had amassed during the American Revolutionary War, and the Congress placed a tax on whiskey (among other things) to help repay those debts. Large producers were assessed a tax of six cents a gallon. Smaller producers, many of whom were Scottish (often Ulster-Scots) descent and located in the more remote areas, were taxed at a higher rate of nine cents a gallon. These rural settlers were short of cash to begin with, and lacked any practical means to get their grain to market, other than fermenting and distilling it into relatively portable spirits. From Pennsylvania to Georgia, the western counties engaged in a campaign of harassment of the federal tax collectors. "Whiskey Boys" also conducted violent protests in Maryland, Virginia, North and South Carolina, and Georgia. This civil disobedience eventually culminated in armed conflict in the Whiskey Rebellion. President George Washington marched at the head of 13,000 soldiers to suppress the insurrection.

According to James Leyburn's The Scotch Irish: A Social History (1962), the Scotch-Irish at first usually referred to themselves simply as Irish, without the qualifier "Scotch" or "Scots", and were called Irish by others. It was not until the mass immigration of Irish in the 1840s caused by the Great Irish Famine (most of whom were Catholic, indigenous, Irish) that the earlier Irish Americans began to call themselves Scotch-Irish to distinguish themselves from these new arrivals. This newer wave of Irish often worked as laborers (and to a lesser extent, tradesmen), typically settling at first in the coastal urban centers to facilitate work, though many would migrate to the interior to labor on large-scale 19th century infrastructure projects such as the canals and, later, railroads. Thus, the Catholic Irish of Boston, New York City, etc., who descended from the 1840s wave, did not often mingle in early years with the Scotch-Irish, who by contrast had in large numbers become well-established years earlier in the rural American interior as small-scale farmers, especially the hill country of the Appalachians and Ozarks.

Number of Scotch-Irish Americans

| Year | Population [18][19][20] |

|---|---|

| 1625 | 1,980 |

| 1641 | 50,000 |

| 1688 | 200,000 |

| 1700 | 250,900 |

| 1702 | 270,000 |

| 1715 | 434,600 |

| 1749 | 1,046,000 |

| 1754 | 1,485,634 |

| 1765 | 2,240,000 |

| 1775 | 2,418,000 |

| 1780 | 2,780,400 |

| 1790 | 3,929,326 |

| 1800 | 5,308,483 |

Population in 1790

According to The Source: A Guidebook of American Genealogy, by Kory L. Meyerink and Loretto Dennis Szucs, the following were the countries of origin for new arrivals coming to the United States before 1790. The regions marked * were part of Great Britain. The ancestry of the 3,929,326 million population in 1790 has been estimated by various sources by sampling last names in the 1790 census and assigning them a country of origin. According to the Harvard Encyclopedia of American Ethnic Groups, there were 400,000 Americans of Irish birth or ancestry in 1790; half of these were descended from Ulster, and half were descended from the other provinces of Ireland. The French were mostly Huguenots. The total U.S. Catholic population in 1790 was probably less than 5%. The Indian population inside territorial U.S. 1790 boundaries was less than 100,000.

| U.S. Historical Populations | ||

|---|---|---|

| Nation | Immigrants Before 1790 | Population 1790-1 |

| England* | 230,000 | 2,100,000 |

| Ireland* | 142,000 | 300,000 |

| Scotland* | 48,500 | 150,000 |

| Wales* | 4,000 | 10,000 |

| Other -5 | 50,000 | 200,000 |

| Total | 950,000 | 3,929,326 |

Ulster-Scottish Canadians

After the creation of British North America in 1763, Protestant Irish, both Irish Anglicans and Ulster-Scottish Presbyterians, migrated over the decades to Upper Canada, some as United Empire Loyalists or directly from Ulster.

The first significant number of Canadian settlers to arrive from Ireland were Protestants from predominantly Ulster and largely of Scottish descent who settled in the mainly central Nova Scotia in the 1760s. Many came through the efforts of colonizer Alexander McNutt. Some came directly from Ulster whilst others arrived after via New England.

Ulster-Scottish migration to Western Canada has two distinct components, those who came via eastern Canada or the US, and those who came directly from Ireland. Many who came West were fairly well assimilated, in that they spoke English and understood British customs and law, and tended to be regarded as just a part of English Canada. However, this picture was complicated by the religious division. Many of the original "English" Canadian settlers in the Red River Colony were fervent Irish loyalist Protestants, and members of the Orange Order.

In 1806, The Benevolent Irish Society (BIS) was founded as a philanthropic organization in St. John's, Newfoundland. Membership was open to adult residents of Newfoundland who were of Irish birth or ancestry, regardless of religious persuasion. The BIS was founded as a charitable, fraternal, middle-class social organization, on the principles of "benevolence and philanthropy", and had as its original objective to provide the necessary skills which would enable the poor to better themselves. Today the society is still active in Newfoundland and is the oldest philanthropic organization in North America.[citation needed]

In 1877, a breakthrough in Irish Canadian Protestant-Catholic relations occurred in London, Ontario. This was the founding of the Irish Benevolent Society, a brotherhood of Irishmen and women of both Catholic and Protestant faiths. The society promoted Irish Canadian culture, but it was forbidden for members to speak of Irish politics when meeting. This companionship of Irish people of all faiths quickly tore down the walls of sectarianism in Ontario. Today, the Society is still operating.

For years, Prince Edward Island had been divided between Catholics and Protestants. In the latter half of the twentieth century, this sectarianism diminished and was ultimately destroyed recently after two events occurred. Firstly, the Catholic and Protestant school boards were merged into one secular institution, and secondly, the practice of electing two MLAs for each provincial riding (one Catholic and one Protestant) was ended.

Scots-Irish as a general term

The usage "Scots-Irish" is relatively recent and regarded by some as an incorrect though well-intended effort to accommodate Scottish preferences. The term has usually been Scotch-Irish in America, as evident in Merriam-Webster dictionaries, where the term Scotch-Irish is recorded from 1744, while Scots-Irish is not recorded until 1972.[21] While modern Scots generally prefer the term "Scots" to "Scotch," in such situations as "Scotch whisky," "Scotch-Irish", "Scotch Baptist," "Scotch egg," and others, the term "Scotch" is preferred. Also, there are many place names in the United States with the latter spelling, such as Scotch Plains, NJ, and several others, yet there are relatively few place names where the first word is Scots.

In the seminal Albion's Seed: Four British Folkways in America (America: a cultural history) historian David Hackett Fischer asserts:

Some historians describe these immigrants as "Ulster Irish" or "Northern Irish." It is true that many sailed from the province of Ulster... part of much larger flow which drew from the lowlands of Scotland, the north of England, and every side of the Irish Sea. Many scholars call these people "Scotch-Irish." That expression is an Americanism, rarely used in Britain and much resented by the people to whom it was attached.

Fischer prefers to speak of "borderers" (referring to the historically war-torn England-Scotland border) as the population ancestral to the "backcountry" "cultural stream" (one of the four major and persistent cultural streams he identifies in American history) and notes the borderers were not purely Celtic but also had substantial Anglo-Saxon and Viking or Scandinavian roots, and were quite different from Celtic-speaking groups like the Scottish Highlanders or Irish (that is, Gaelic-speaking and Roman Catholic).

An example of the use of the term is found in A History of Ulster: "Ulster Presbyterians – known as the 'Scotch Irish' – were already accustomed to being on the move, and clearing and defending their land."[22]

Other terms used to describe the descendants of Protestants from the border country of England and Scotland that first migrated to Ulster and later re-migrated to North America include "Northern Irish" or "Irish Presbyterians."

In America, the historic name for these people is "Scotch-Irish", and depending on the label used, can draw ire from one or more party. However, as one scholar observed, "...in this country [USA], where they have been called Scotch-Irish for over two hundred years, it would be absurd to give them a name by which they are not known here... Here their name is Scotch-Irish; let us call them by it." [23]

History of the name Scotch-Irish

Although referenced by Merriam-Webster dictionaries as having first appeared in 1744, the American term "Scotch-Irish" is undoubtedly older.

An affidavit of William Patent, dated March 15, 1689, in a case against a Mr. Matthew Scarbrough in Somerset County, Maryland, quotes Mr. Scarbrough as saying, "...it was no more sin to kill me then to kill a dogg, or any Scotch Irish dogg..."[24]

Leyburn cites several early American uses of the term.[25]

- The earliest is a report in June 1695, by Sir Thomas Laurence, Secretary of Maryland, that "In the two counties of Dorchester and Somerset, where the Scotch-Irish are numerous, they clothe themselves by their linen and woolen manufactures."

- In September 1723, Rev. George Ross, Rector of Immanuel Church in New Castle, Delaware, wrote in reference to their anti-Church of England stance that, "They call themselves Scotch-Irish,...and the bitterest railers against the church that ever trod upon American ground."

- Another Church of England clergyman from Lewes, Delaware, commented in 1723 that "...great numbers of Irish (who usually call themselves Scotch-Irish) have transplanted themselves and their families from the north of Ireland."

- During the 1740s, a Marylander was accused of having murdered the sheriff of Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, after calling the sheriff and his assistants "damned Scotch-Irish sons of bitches."[26]

The Oxford English Dictionary says the first use of the term "Scotch-Irish" came in Pennsylvania in 1744. Its citations are:

- 1744 W. MARSHE Jrnl. 21 June in Collections of the Massachuseets Historical Society. (1801) 1st Ser. VII. 177: 'The inhabitants [of Lancaster, Pa.] are chiefly High-Dutch, Scotch-Irish, some few English families, and unbelieving Israelites."

- 1789 J. MORSE Amer. Geogr. 313: "[The Irish of Pennsylvania] have sometimes been called Scotch-Irish, to denote their double descent."

- 1876 BANCROFT Hist. U.S. IV. iii. 333: "But its convenient proximity to the border counties of Pennsylvania and Virginia had been observed by Scotch-Irish Presbyterians and other bold and industrious men."

- 1883 Harper's Mag. Feb. 421/2: "The so-called Scotch-Irish are the descendants of the Englishmen and Lowland Scotch who began to move over to Ulster in 1611."

A false myth claims that Queen Elizabeth used the term. Another myth is that Shakespeare used the spelling 'Scotch' as a proper noun, but his only use of the word in any of his writings is as a verb, as in scotching a snake, being scotched, etc.

It was also used to differentiate from either the Anglo-Irish, Irish Catholics, or immigrants who came directly from Scotland.

The word "Scotch" was the favoured adjective as a designation — it literally means "... of Scotland". People in Scotland refer to themselves as Scots, or adjectivally/collectively as Scots or as being Scottish, rather than Scotch.

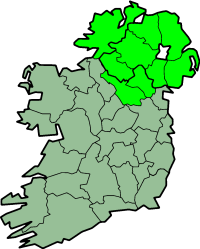

Geographical distribution

Finding the coast already heavily settled, most groups of settlers from the north of Ireland moved into the "western mountains", where they populated the Appalachian regions and the Ohio Valley. Others settled in northern New England, The Carolinas, Georgia and north-central Nova Scotia.

In the United States Census, 2000, 4.3 million Americans (1.5% of the U.S. population) claimed Scotch-Irish ancestry, though author James Webb suggests estimates that the true number of Scotch-Irish in the U.S. is more in the region of 27 million. [1] Two possible reasons have been suggested[who?] for the disparity of the figures of the census and the estimation. The first is that Scotch-Irish may quite often regard themselves as simply having either Irish ancestry (which 10.8% of Americans reported) or Scottish ancestry (reported by 4.9 million or 1.7% of the total population). The other is that most of the descendants of this group have integrated themselves, through intermarriage with other ethnicities of similar faiths, into an American society that had long been a rurally dispersed and Protestant majority. Therefore they, like many English Americans or German Americans, do not feel the need to identify with their ancestors as strongly as perhaps the more recent Catholic Irish Americans or Italian Americans, who had not traditionally married outside their faiths and often found partners in dense urban neighborhoods of their own ethnicity.

Interestingly, the areas where the most Americans reported themselves in the 2000 Census only as "American" with no further qualification (e.g. Kentucky, north-central Texas, and many other areas in the Southern US; overall 7% of Americans reported "American") are largely the areas where many Scotch-Irish settled, and are in complementary distribution with the areas which most heavily report Scotch-Irish ancestry, though still at a lower rate than "American" (e.g. western North Carolina and eastern Tennessee, western Pennsylvania, northern New England, south-central and far northern Texas, westernmost Florida Panhandle, many rural areas in the Northwest); see Maps of American ancestries. Perhaps a combination of these factors results in the relatively low figures as reported in the census,[original research?] though there does appear[who?] to be an increased interest in the U.S. in recent years in Scotch-Irish ancestry.[citation needed]

Religion in the New World

Initially the Scotch-Irish immigrants to North America in the eighteenth century were defined by their Presbyterianism.[27] Many of the settlers in the Plantation of Ulster had been from dissenting/non-conformist religious groups which professed a strident Calvinism. These included mainly Lowland Scot Presbyterians, but also English Puritans and Quakers, French Huguenots and German Palatines. These Calvinist groups mingled freely in church matters, and religious belief was more important than nationality, as these groups aligned themselves against both their Catholic Irish and Anglican English neighbors.[28] After their arrival in the New World, the predominantly Presbyterian Scotch-Irish began to move further into the mountainous back-country of Virginia and the Carolinas. The establishment of many settlements in the remote back-country put a strain on the ability of the Presbyterian Church to meet the new demand for qualified, college-educated clergy. Religious groups such as the Baptists and Methodists had no higher education requirement for their clergy to be ordained, and these groups readily provided ministers to meet the demand of the growing Scotch-Irish settlements.[29] By about 1810, Baptist and Methodist churches were in the majority, and the descendants of the Scotch-Irish today remain predominantly Baptist or Methodist.[30]

Notable Americans of Scotch-Irish descent

American Presidents

Many American presidents have ancestral links to Ulster, including three whose parents were born in Ulster. The Irish Protestant vote in the U.S. has not been studied nearly as much as have the Catholic Irish. (On the Catholic vote see Irish Americans). In the 1820s and 1830s, supporters of Andrew Jackson emphasized his Irish background, as did James Knox Polk, but since the 1840s it has been uncommon for a Protestant politician in America to be identified as Irish, but rather as 'Scotch-Irish'. In Canada, by contrast, Irish Protestants remained a cohesive political force well into the twentieth century, identified with the then Conservative Party of Canada and especially with the Orange Institution, although this is less evident in today's politics.[31]

More than one-third of all U.S. Presidents had substantial ancestral origins in the northern province of Ireland (Ulster). President Bill Clinton spoke proudly of that fact, and his own ancestral links with the province, during his two visits to Ulster. Like most US citizens, most US presidents are the result of a "melting pot" of ancestral origins.

Clinton is one of at least seventeen Chief Executives descended from emigrants to the United States from the north of Ireland. While many of the Presidents have typically Ulster-Scots surnames – Jackson, Johnson, McKinley, Wilson – others, such as Roosevelt and Cleveland, have links which are less obvious.

- Andrew Jackson

- 7th President, 1829-37: He was born in the predominantly Ulster-Scots Waxshaws area of South Carolina two years after his parents left Boneybefore, near Carrickfergus in County Antrim. A heritage centre in the village pays tribute to the legacy of 'Old Hickory', the People's President.

- James Knox Polk

- 11th President, 1845-49: His ancestors were among the first Ulster-Scots settlers, emigrating from Coleraine in 1680 to become a powerful political family in Mecklenberg County, North Carolina. He moved to Tennessee and became its Governor before winning the Presidency.

- James Buchanan

- 15th President, 1857-61: Born in a log-cabin (which has been relocated to his old school in Mercersburg, Pennsylvania), 'Old Buck' cherished his origins: "My Ulster blood is a priceless heritage". The Buchanans were originally from Deroran, near Omagh in County Tyrone where the ancestral home still stands.

- Andrew Johnson

- 17th President, 1865-69: His grandfather left Mounthill, near Larne in County Antrim around 1750 and settled in North Carolina. Andrew worked there as a tailor and ran a successful business in Greeneville, Tennessee Tennessee, before being elected Vice-President. He became President following Abraham Lincoln's assassination.

- Ulysses S. Grant

- 18th President, 1869-77: The home of his maternal great-grandfather, John Simpson, at Dergenagh, County Tyrone, is the location for an exhibition on the eventful life of the victorious Civil War commander who served two terms as President. Grant visited his ancestral homeland in 1878.

- Chester A. Arthur

- 21st President, 1881-85: His election was the start of a quarter-century in which the White House was occupied by men of Ulster-Scots origins. His family left Dreen, near Cullybackey, County Antrim, in 1815. There is now an interpretive centre, alongside the Arthur Ancestral Home, devoted to his life and times.

- Grover Cleveland

- 22nd and 24th President, 1885-89 and 1893-97: Born in New Jersey, he was the maternal grandson of merchant Abner Neal, who emigrated from County Antrim in the 1790s. He is the only President to have served non-consecutive terms.

- Benjamin Harrison

- 23rd President, 1889-93: His mother, Elizabeth Irwin, had Ulster-Scots roots through her two great-grandfathers, James Irwin and William McDowell. Harrison was born in Ohio and served as a Brigadier General in the Union Army before embarking on a career in Indiana politics which led to the White House.

- William McKinley

- 25th President, 1897-1901: Born in Ohio, the descendant of a farmer from Conagher, near Ballymoney, County Antrim, he was proud of his ancestry and addressed one of the national Scotch-Irish Congresses held in the late 19th century. His second term as President was cut short by an assassin's bullet.

- Theodore Roosevelt

- 26th President, 1901-09: His mother, Mittie Bulloch, had Ulster Scots ancestors who emigrated from Glenoe, County Antrim, in May 1729. Teddy Roosevelt's oft-repeated praise of his "bold and hardy race" is evidence of the pride he had in his Scotch-Irish connections. Ironically, he is also the man who said: "But a hyphenated American is not an American at all. This is just as true of the man who puts "native"* before the hyphen as of the man who puts German or Irish or English or French before the hyphen." [2] (*Roosevelt was referring to "nativists", not American Indians, in this context)

- Woodrow Wilson

- 28th President, 1913-21: Of Ulster-Scot descent on both sides of the family, his roots were very strong and dear to him. He was grandson of a printer from Dergalt, near Strabane, County Tyrone, whose former home is open to visitors. Throughout his career he reflected on the influence of his ancestral values on his constant quest for knowledge and fulfilment.

- Richard Milhous Nixon

- 37th President, 1969-74: The Nixon ancestors left Ulster in the mid-18th century; the Quaker Milhous family ties were with County Antrim and County Kildare.

Other occupants of the White House said to have some family ties with Ulster include Presidents John Adams, John Quincy Adams, James Monroe, Dwight D. Eisenhower, Harry S. Truman, Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan, George H. W. Bush and George W. Bush.[32]

Quotes

The gentle terms of republican race, mixed rabble of Scotch, Irish and foreign vagabonds, descendants of convicts, ungrateful rebels, &c. are some of the sweet flowers of English rhetorick, with which our colonists have of late been regaled. [3] (Benjamin Franklin, 1765)

This cartoon, circulated after the 1763 Conestoga massacre, criticizes the Quakers for their support of Native Americans at the expense of German and Scotch-Irish backcountry settlers. Here, a "broad brim'd" Quaker and Native American each ride as a burden on the backs of "Hibernians." Historical Society of Pennsylvania

The Quakers did not appreciate their interference in politics and were especially unhappy with them when the Scot-Irish gained control of the Pennsylvania Assembly in 1756. Who were the Scot-Irish?

See also

- List of Scots-Irish Americans

- Appalachia

- Celt

- Scottish American

- Irish American

- Redneck

- Whiskey Rebellion

- Hatfield-McCoy feud

- Ulster American Folk Park

- Battle of Kings Mountain

References

- ^ "US Census Bureau 2005 American Community Survey, Scotch-Irish ancestry". Retrieved 2007-04-28.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Scholarly estimates vary, but here are a few: "more than a quarter-million", Fischer, David Hackett, Albion's Seed: Four British Folkways in America Oxford University Press, USA (March 14, 1989), pg. 606; "200,000", Rouse, Parke Jr., The Great Wagon Road, Dietz Press, 2004, pg. 32; "...250,000 people left for America between 1717 and 1800...20,000 were Anglo-Irish, 20,000 were Gaelic Irish, and the remainder Ulster-Scots or Scotch-Irish...", Blethen, H.T. & Wood, C.W., From Ulster to Carolina, North Carolina Division of Archives and History, 2005, pg. 22; "more than 100,000", Griffin, Patrick, The People with No Name, Princeton Univ Press, 2001, pg 1; "200,000", Leyburn, James G., The Scotch-Irish: A Social History, Univ of NC Press, 1962, pg. 180; "225,000", Hansen, Marcus L., The Atlantic Migration, 1607-1860, Cambridge, Mass, 1940, pg. 41; "250,000", Dunaway, Wayland F. The Scotch-Irish of Colonial Pennsylvania, Genealogical Publishing Co (1944), pg. 41; "300,000", Barck, O.T. & Lefler, H.T., Colonial America, New York (1958), pg. 285.

- ^ Leyburn, James G., The Scotch-Irish: A Social History, Univ of NC Press, 1962, ppg. 327-334.

- ^ Robinson, Philip, The Plantation of Ulster, St. Martin's Press, 1984, ppg. 109-128, and Rowse, A.L., The Expansion of Elizabethan England, Harper & Row:New York, 1965, pg. 28.

- ^ U.S. Census Bureau, 2005 American Community Survey, Scotch-Irish Ancestry.

- ^ Ohlmeyer, Jane and John Kenyon, The Civil Wars, p. 278, 'William Petty's figure of 37,000 Protestants massacred... is far too high, perhaps by a factor of ten, certainly more recent research suggests that a much more realistic figure is roughly 4,000 deaths.'

- ^ Staff, Secrets of Lough Kernan BBC, Legacies UK history local to you, website of the BBC. Accessed 17 December 2007

- ^ The Rebellion of 1641-42

- ^ Template:Harvard reference p.143

- ^ Scots-Irish By Alister McReynolds, writer and lecturer in Ulster-Scots studies, nitakeacloserlook.gov.uk

- ^ "...summer of 1717...", Fischer, David Hackett, Albion's Seed: Four British Folkways in America, Oxford University Press, USA (March 14, 1989), pg. 606; "...early immigration was small,...but it began to surge in 1717.", Blethen, H.T. & Wood, C.W., From Ulster to Carolina, North Carolina Division of Archives and History, 2005, pg. 22; "Between 1718 and 1775", Griffin, Patrick, The People with No Name, Princeton Univ Press, 2001, pg 1; etc.

- ^ Rev. A. L. Perry, Scotch-Irish in New England:Taken from The Scotch-Irish in America: Proceedings and Addresses of the Second Congress at Pittsburgh,1890.

- ^ Crozier 1984; Montgomery 1989, 2001

- ^ Leyburn, James G., The Scotch-Irish: A Social History, Univ of NC Press, 1962; and Rouse, Parke Jr., The Great Wagon Road, Dietz Press, 2004

- ^ Leyburn, James G., The Scotch-Irish: A Social History, Univ of NC Press, 1962.

- ^ Philip H. Bagenal, The American Irish and their Influence on Irish Politics, London, 1882, pp 12-13.

- ^ John C. Campbell, The Southern Highlander and his Homeland, University Press of Kentucky, 1969, and Theodore Roosevelt, The Winning of the West, G. P. Putnam's Sons, New York, 1906.

- ^ Census Research

- ^ United States Timeline population

- ^ United States population 1790-1990

- ^ http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/scotch-irish; http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/scots-irish

- ^ A History of Ulster, Jonathan Bardon, The Blackstaff Press Limited, Northern Ireland, 1992. Emigration to United States and Scotch-Irish, ppgs. 208-210.

- ^ The Scotch-Irish of Colonial America, Wayland F. Dunaway, 1944, University of North Carolina Press

- ^ http://homepages.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~merle/Articles/OldestUseSI.htm

- ^ Leyburn, James G., The Scotch-Irish: A Social History, Univ of NC Press, 1962, pg 330.

- ^ Leyburn, James G., The Scotch-Irish: A Social History, Univ of NC Press, 1962, which cites Hubertis Cummings, Richard Peters, Provincial Secretary and Cleric, 1704-1776, Philadelphia, 1944, pg. 142.

- ^ Leyburn, James G., The Scotch-Irish: A Social History, Univ of NC Press, 1962, pg 273.

- ^ Hanna, Charles A., The Scotch-Irish: or the Scot in North Britain, North Ireland, and North America, G. P. Putnam's Sons, new York, 1902, pg. 163

- ^ Griffin, Patrick, The People with No Name: Ireland's Ulster Scots, America's Scots Irish, and the Creation of a British Atlantic World, Princeton Univ Press, 2001, ppg 164-165.

- ^ Leyburn, James G., The Scotch-Irish: A Social History, Univ of NC Press, 1962, pg 295.

- ^ Presidents of Ulster-Scots heritage

- ^ The Bushes' ancestors include William Holliday from Rathfriland.

Secondary sources

- Bailyn, Bernard and Philip D. Morgan, eds. Strangers Within the Realm: Cultural Margins of the First British Empire (1991), scholars analyze colonial migrations. excerpts online

- Blethen, Tyler. ed. Ulster and North America: Transatlantic Perspectives on the Scotch-Irish (1997; ISBN 0-8173-0823-7), scholarly essays.

- Carroll, Michael P. "How the Irish Became Protestant in America," Religion and American Culture Winter 2006, Vol. 16, No. 1, Pages 25–54

- Dunaway, Wayland F. The Scotch-Irish of Colonial Pennsylvania (1944; reprinted 1997; ISBN 0-8063-0850-8), solid older scholarly history.

- Fischer, David Hackett. Albion's Seed: Four British Folkways in America (1991), major scholarly study tracing colonial roots of four groups of immigrants, Irish, English Puritans, English Cavaliers, and Quakers.

- Glazier, Michael, ed. The Encyclopedia of the Irish in America, (1999), the best place to start--the most authoritative source, with essays by over 200 experts, covering both Catholic and Protestants.

- Griffin, Patrick. The People with No Name: Ireland's Ulster Scots, America's Scots Irish, and the Creation of a British Atlantic World: 1689-1764 (2001; ISBN 0-691-07462-3) solid academic monograph.

- Leyburn, James G. Scotch-Irish: A Social History (1999; ISBN 0-8078-4259-1) written by academic but out of touch with scholarly literature after 1940

- McDonald, Forrest, and Grady McWhinney, "The Antebellum Southern Herdsman: A Reinterpretation," Journal of Southern History 41 (1975) 147-66; highly influential economic interpretation; online at JSTOR through most academic libraries. Their Celtic interpretation says Scots-Irish resembled all other Celtic groups; they were warlike herders (as opposed to peaceful farmers in England), and brought this tradition to America. James Webb has popularized this thesis.

- Berthoff, Rowland. "Celtic Mist over the South," Journal of Southern History 52 (1986): 523-46 is a strong attack; rejoinder on 547-50

- McWhiney, Grady. Attack and Die: Civil War Military Tactics and the Southern Heritage (1984).

- McWhiney, Grady. Cracker Culture: Celtic Ways in the Old South (1988). Major exploration of cultural folkways.

- Meagher, Timothy J. The Columbia Guide to Irish American History. (2005), overview and bibliographies; includes the Catholics.

- Miller, Kerby. Emigrants and Exiles: Ireland and the Irish Exodus to North America (1988). Highly influential study.

- Miller, Kerby, et al. eds. Journey of Hope: The Story of Irish Immigration to America (2001), major source of primary documents.

- Porter, Lorle. A People Set Apart: The Scotch-Irish in Eastern Ohio (1999; ISBN 1-887932-75-5) highly detailed chronicle.

- Quinlan, Kieran. Strange Kin: Ireland and the American South (2004), critical analysis of Celtic thesis.

- Sletcher, Michael, ‘Scotch-Irish’, in Stanley I. Kutler, ed., Dictionary of American History, (10 vols., New York, 2002).

Popular history and literature

- Bageant, Joseph L. Deer Hunting with Jesus: Dispatches From America's Class War (2007; ISBN 978-1-921215-78-0) Cultural discussion and commentary of Scots-Irish descendants in the USA.

- Baxter, Nancy M. Movers: A Saga of the Scotch-Irish (The Heartland Chronicles) (1986; ISBN 0-9617367-1-2) Novelistic.

- Chepesiuk, Ron. The Scotch-Irish: From the North of Ireland to the Making of America (ISBN 0-7864-0614-3)

- Dunbar-Ortiz, Roxanne. "Red Dirt: Growing Up Okie" (2006; ISBN 0-8061-3775-4) literary/historical family memoir of Scotch-Irish Missouri/Oklahoma family.

- Glasgow, Maude. The Scotch-Irish in Northern Ireland and in the American Colonies (1998; ISBN 0-7884-0945-X)

- Greeley, Andrew. Encyclopedia of the Irish in America

- Johnson, James E. Scots and Scotch-Irish in America (1985, ISBN 0-8225-1022-7) short overview for middle schools

- Kennedy, Billy. Faith & Freedom: The Scots-Irish in America (1999; ISBN 1-84030-061-2) Short, popular chronicle; he has several similar books on geographical regions

- Kennedy, Billy. The Scots-Irish in the Carolinas (1997; ISBN 1-84030-011-6)

- Kennedy, Billy. The Scots-Irish in the Shenandoah Valley (1996; ISBN 1-898787-79-4)

- Lewis, Thomas A. West From Shenandoah: A Scotch-Irish Family Fights for America, 1729-1781, A Journal of Discovery (2003; ISBN 0-471-31578-8)

- Webb, James. Born Fighting: How the Scots-Irish Shaped America (2004; ISBN 0-7679-1688-3) novelistic approach; special attention to his people's war with English in America.

- Webb, James. Why You Need to Know the Scots-Irish (10-3-2004; Parade magazine). Article recognizes the great Scots-Irish people and their accomplishments.

External links

- The Ulster-Scots Society of America

- Ulster-Scots Language Society

- Scotch-Irish or Scots-Irish: What's in a Name?

- Ulster-Scots Agency

- Ulster-Scots Online

- Institute of Ulster-Scots

- Scotch Irish.Net

- Theodore Roosevelt's genealogy

- The Scotch-Irish in America (by Henry Jones Ford)

- Origin of the Scotch-Irish, Ch. 5 in Sketches of North Carolina by William Henry Foote (1846) - full-text history

- Chronicles of the Scotch-Irish Settlement in Virginia - Extracted from the Original Court Records of Augusta County 1745-1800 by Lyman Chalkley

- Peyton's History of Augusta County, Virginia (1882) - full-text history with many mentions of Scotch-Irish

- Waddell's Annals of Augusta County, Virginia, from 1726 to 1871, Second Ed. (1902) - full-text history with many mentions of Scotch-Irish

- "Ideas & Trends: Southern Curse; Why America's Murder Rate Is So High", New York Times, July 26, 1998