1966 Atlantic hurricane season

| 1966 Atlantic hurricane season | |

|---|---|

Season summary map | |

| Seasonal boundaries | |

| First system formed | June 4, 1966 |

| Last system dissipated | November 11, 1966 |

| Strongest storm | |

| Name | Inez |

| • Maximum winds | 150 mph (240 km/h) (1-minute sustained) |

| • Lowest pressure | 929 mbar (hPa; 27.43 inHg) |

| Seasonal statistics | |

| Total depressions | 14 |

| Total storms | 11 |

| Hurricanes | 7 |

| Major hurricanes (Cat. 3+) | 3 |

| Total fatalities | 1,096 total |

| Total damage | $436.6 million (1966 USD) |

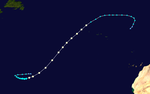

The 1966 Atlantic hurricane season featured the tropical cyclone with the longest track in the Atlantic basin – Hurricane Faith.[1] Also during the year, the Miami, Florida Weather Office was re-designated the National Hurricane Center. The season officially began on June 1, and lasted until November 30. These dates conventionally delimit the period of each year when most tropical cyclones form in the Atlantic basin. It was a near average season in terms of tropical storms, with a total of 11 named storms. The first system, Hurricane Alma, developed over eastern Nicaragua on June 4. Alma brought severe flooding to Honduras and later to Cuba, after crossing the western Caribbean Sea. The storm also brought relatively minor impact to the Southeastern United States. Alma caused 91 deaths and about $210.1 million (1966 USD)[nb 1] in damage.

Hurricanes Becky, Celia, and Dorothy, and Tropical Storm Ella all resulted in minimal or no impact on land. The next system, Hurricane Faith, developed near Cape Verde on August 21. It tracked westward across the Atlantic Ocean until north of Hispaniola. After paralleling the East Coast of the United States, Faith moved northeastward across the open Atlantic and later became extratropical near Scotland on September 6. Overall, Faith traveled about 6,850 mi (11,020 km) across the Atlantic. Although it never made landfall, the storm generated rough seas that resulted in five deaths. The two next tropical storms – Greta and Hallie – caused negligible impact.

The strongest tropical cyclone of the season was Hurricane Inez, a powerful Category 4 hurricane that devastated a large majority of the Caribbean, the Florida Keys, and parts of Mexico. Throughout its path, the storm caused about $226.5 million in damage and more than 1,000 deaths. Tropical Storm Judith left only minor impacts in the Windward Islands. The final system, Hurricane Lois, developed east of Bermuda on November 4. Later in its duration, Lois passed west of the Azores, bringing gale-force winds to Corvo Island. The storm became extratropical northeast of the islands on November 11. A possible tropical cyclone in June and July and another in July brought minor damage to Florida and Louisiana, respectively. Overall, the storms of this season collectively caused at least 1,096 fatalities and about $436.6 million in damage.

Season summary

The Atlantic hurricane season officially began on June 1.[2] During the year, the Miami, Florida Weather Office was re-designated the National Hurricane Center.[3] It was a near average season in which eleven tropical storms formed, compared with the 1966–2009 average of 11.3 named storms. Seven of these reached hurricane status, slightly above of the 1966–2009 average of 6.2. Furthermore, three storms reached major hurricane status,[nb 2] with the 1950-2000 mean being 2.3.[5][6] Three hurricanes and one tropical storm made landfall during the season,[7] causing at least 1,096 deaths and $436.6 million in damage.[8] Hurricane Faith also caused fatalities, despite remaining well offshore.[6] The season officially ended on November 30.[2]

The first storm, Hurricane Alma, developed over eastern Nicaragua on June 4. Alma crossed the Caribbean Sea and struck Cuba. The storm made another landfall in Florida as a hurricane on June 9. This marked the earliest United States hurricane landfall since a hurricane in May and June of 1825. Alma continued northeastward across the Southeastern United States until becoming extratropical offshore Virginia on June 13.[7] Later that month, another tropical depression developed.[6] The month of July was highly active, with four named storms – Becky, Celia, Dorothy, and Ella.[7] Additionally, a tropical depression developed in the Gulf of Mexico.[6] However, tropical cyclogenesis then halted for more than three weeks, until Hurricane Faith developed on August 21.[7] On average, three or four named storms form in August.[9]

Four tropical cyclones developed in September, including tropical storms Greta, Hallie and Judith, as well as Hurricane Inez. Peaking as a strong Category 4 hurricane on the Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale with winds of 150 mph (240 km/h), Inez was the strongest tropical cyclone of the season. Although Inez persisted into October, no other system developed that month.[7] Two named storms usually form in October.[10] The final tropical cyclone, Hurricane Lois, existed from November 4 to November 11.[7]

The season's activity was reflected with an accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) rating of 145.[11] ACE is, broadly speaking, a measure of the power of the hurricane multiplied by the length of time it existed, so storms that last a long time, as well as particularly strong hurricanes, have high ACEs. It is only calculated for full advisories on tropical systems at or exceeding 39 mph (63 km/h), which is tropical storm strength.[12]

Systems

Hurricane Alma

| Category 3 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | June 4 – June 13 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 125 mph (205 km/h) (1-min); 970 mbar (hPa) |

In early June, a dissipating trough extended southward into the western Caribbean Sea. A surface circulation formed,[6] and thus, a tropical depression developed over eastern Nicaragua on June 4.[7] While moving through Honduras, it dropped heavy rainfall that killed at least 73 people in the city of San Rafael.[6] Offshore northern Honduras, the system produced heavy rainfall in Swan Island.[13] The depression moved northeastward and intensified into Tropical Storm Alma on June 6, and a hurricane six hours later.[7] Alma crossed western Cuba, causing heavy crop damage and water shortages.[14][15] Over 1,000 houses were destroyed,[16] and damage was estimated around $200 million.[6] The storm killed 12 people in the country.[16]

After crossing Cuba, Alma intensified further to reach winds of 125 mph (205 km/h) in the Gulf of Mexico.[7] The hurricane passed west of Key West, Florida, causing a power outage and flooding.[17] Alma dropped heavy rainfall and produced winds across most of Florida, which damaged crops and caused scattered power outages.[6][18] The hurricane weakened before moving ashore near Apalachee Bay on June 9.[7] This was the earliest date of landfall in the United States since 1825. Damage in Florida was estimated at $10 million, and there were six deaths in the state.[6] Alma crossed southeastern Georgia as a tropical storm,[7] damaging a few houses and causing light damage.[19] The storm re-intensified into a hurricane over the western Atlantic Ocean, and its outer rainbands dropped heavy rainfall in Wilmington, North Carolina.[6] Alma encountered colder water temperatures and transitioned into an extratropical cyclone on June 13. Its remnants dissipated a day later over Massachusetts.[6][7]

Hurricane Becky

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | July 1 – July 3 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 75 mph (120 km/h) (1-min); 985 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical depression formed 300 mi (485 km) southeast of Bermuda on July 1 at 18:00 UTC,[7] as confirmed by ESSA 2 satellite. The depression intensified while heading northeastward under an upper-level trough.[6] At 06:00 UTC on July 2, the system became Tropical Storm Becky and reached hurricane status only six hours later.[7] Around that time, Becky attained its peak intensity with maximum sustained winds of 75 mph (120 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 985 mbar (29.1 inHg).[7] After coming under the influence of a cold low, Becky turned to the northwest toward Atlantic Canada on July 3. Becky encountered cooler sea surface temperatures, and became extratropical near Nova Scotia later that day.[6]

Hurricane Celia

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | July 13 – July 21 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 80 mph (130 km/h) (1-min); 995 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave developed into a tropical depression at 12:00 UTC on July 13, while located about 200 mi (320 km) northeast of the Leeward Islands. While moving northwestward, a reconnaissance aircraft flight observed tropical storm force winds.[6] Thus, the depression was upgraded to Tropical Storm Celia at 00:00 UTC on July 14.[7] Curving westward, Celia weakened to a tropical depression around midday on July 15,[7] and was operationally believed to have degenerated into a remnant low pressure.[6] Between July 17 and July 19, the storm moved across the Bahamas, before turning northeastward.[7]

By July 20, the system re-intensified into a tropical storm.[7] Several hours later, a reconnaissance aircraft observed sustained winds of 80 mph (130 km/h). As a result, Celia was upgraded to a hurricane at 18:00 UTC on July 20.[6] Early the next day, the storm attained its minimum barometric pressure of 995 mbar (29.4 inHg).[7] Celia accelerated northeast in advance of a frontal trough and began losing tropical characteristics.[6] Around the time of landfall in eastern Nova Scotia at 18:00 UTC on July 21, the storm became extratropical. The remnants weakened and struck Newfoundland before dissipating the next day.[7] Only light rainfall was observed in Atlantic Canada and Quebec.[20]

Hurricane Dorothy

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | July 22 – July 30 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 85 mph (140 km/h) (1-min); 989 mbar (hPa) |

In late July, a low-level disturbance situated over the central Atlantic Ocean encountered a vigorous shortwave trough and developed into a surface low pressure area on July 22.[6] At 18:00 UTC, a tropical depression formed about 800 mi (1,300 km) southwest of Flores Island in the Azores.[7] Initially, the depression had extratropical features and lacked tropical characteristics, such as a warm core and a well-developed central dense overcast. A weather ship in the area indicated an influx of baroclinity, suggesting that Dorothy derived its energy through non-tropical processes.[21] Around 12:00 UTC on July 23, the depression strengthened into Tropical Storm Dorothy. Thereafter, it moved in quasi-stationary motion to the northwest and continued to intensify, reaching hurricane status late on July 24.[7]

Upon reaching hurricane intensity,[6] Dorothy possessed tropical characteristics, with evidence of a weak warm core beginning on July 25.[21] The hurricane moved in a semi-circular path, and at 12:00 UTC the next day, Dorothy attained its minimum barometric pressure of 989 mbar (29.2 inHg). Later on July 26, the system curved north-northeastward. Further strengthening occurred and at 00:00 UTC on July 28, Dorothy attained its maximum sustained wind speed of 85 mph (140 km/h).[7] Moving across colder sea surface temperatures, the hurricane began weakening and fell to tropical storm status early on July 29.[6] Dorothy continued to weaken and became extratropical around 18:00 UTC the following day, while located about 610 mi (980 km) north-northwest of Corvo Island in the Azores. The remnants continued northwestward and dissipated on July 31.[7]

Tropical Storm Ella

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | July 22 – July 28 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min); 1008 mbar (hPa) |

ESSA 2 satellite imagery showed a cloud mass with a possible circulation on July 22.[6] Later that day, a tropical depression developed at 12:00 UTC, while located about 765 mi (1,230 km) southwest of the southernmost islands of Cape Verde. The depression slowly intensified and became Tropical Storm Ella late on July 24.[7] However, it remained generally poorly organized and at times resembled a tropical wave.[6] The storm intensified slightly further and at 12:00 UTC on July 26, it peaked with maximum sustained winds of 50 mph (85 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 1,008 mbar (29.8 inHg).[7] On July 28, outflow from Hurricane Dorothy weakened the storm to a tropical depression.[6][7] Ella dissipated shortly thereafter, while located about 255 mi (410 km) northeast of Grand Turk Island.[7]

Hurricane Faith

| Category 3 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 21 – September 6 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 125 mph (205 km/h) (1-min); 950 mbar (hPa) |

An area of disturbed weather emerged into the Atlantic Ocean from the west coast of Africa in mid-August.[6] It developed into a tropical depression while located between Cape Verde and the west coast of Africa on August 21. Tracking westward, the depression intensified and became Tropical Storm Faith on the following day. Moving westward across the Atlantic Ocean, it continued to slowly strengthen, reaching hurricane status early on August 23. About 42 hours later, Faith reached an initial peak with winds of 105 mph (165 km/h), before weakening slightly on August 26.[7] Located near the Lesser Antilles, the outer bands of Faith produced gale-force winds in the region, especially Puerto Rico, the Virgin Islands, and Antigua.[6] Minor damage to boats and jetties occurred as far south as Trinidad and Tobago.[22]

By August 28, the storm began to re-intensify, after curving north-northwestward near The Bahamas. At 00:00 UTC on the following day, Faith peaked with winds of 125 mph (205 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 950 mbar (28 inHg). Eventually, the storm weakened back to a Category 2 hurricane and re-curved to the northeast.[7] One person drowned in the western Atlantic after his ship sank.[6] Heavy rainfall and strong winds pelted Bermuda, though no damage occurred.[23] The storm maintained nearly the same intensity for several days, while tracking northeastward into the far North Atlantic Ocean. Faith weakened while north of Scotland and became extratropical near the Faroe Islands on September 6.[7] Three other drowning deaths occurred in the North Sea near Denmark.[6] A fifth death occurred after a man succumbed to injuries sustained during a boating incident related to the storm.[24] The remnants of Faith moved across Scandinavia and Russia for the next several days. In Norway, heavy rainfall from the storm caused record high glacier melting, resulting in "large" flooding in some areas.[25] Crossing into Russia, the remnants of Faith remained identifiable until reaching Franz Josef Land on September 15.[6]

Tropical Storm Greta

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 1 – September 7 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min); 1004 mbar (hPa) |

A weather report from the SS San Marcial and Nimbus 2 satellite imagery showed that a circulation developed within a cloud mass to the east of the Lesser Antilles on September 1.[6] As a result, a tropical depression formed about 745 mi (1,199 km) east of Barbados at 12:00 UTC. The depression moved west-northwestward and remained weak for a few days.[7] Based on reconnaissance aircraft flight observing sustained winds of 58 mph (93 km/h), the depression was upgraded to Tropical Storm Greta at 18:00 UTC on September 4. Early the next day, Greta attained its peak intensity with maximum sustained winds of 60 mph (95 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 1,004 mbar (29.6 inHg). The storm began weakening on September 6 and fell to tropical depression intensity around midday.[7] Late on September 7, Greta merged with a pre-frontal cloud mass between the East Coast of the United States and Bermuda.[6]

Tropical Storm Hallie

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 20 – September 22 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min); 997 mbar (hPa) |

Satellite imagery from ESSA 2 indicated that a large area of disturbed weather began merging with a frontal band in the southwestern Gulf of Mexico. After an increase in convective activity and satellite imagery revealing a closed circulation on September 20, the system was classified as a tropical depression. By early on the following day, the depression was upgraded to Tropical Storm Hallie. After initially remaining stationary, Hallie eventually began a southwestward drift toward Mexico.[6] Around 12:00 UTC on September 21, the storm made landfall near Nautla, Veracruz.[7] Due to cool, dry air, as well as land interaction with the mountainous terrain of Mexico,[6] Hallie rapidly weakened inland and dissipated by 00:00 UTC on September 22.[7] While passing near Nautla, winds of 40 mph (65 km/h) and heavy rainfall were reported.[6]

Hurricane Inez

| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 21 – October 11 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 150 mph (240 km/h) (1-min); 929 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave developed into a tropical depression well east of the Lesser Antilles on September 21.[6] It moved slowly westward and strengthened into Tropical Storm Inez on September 24. The storm strengthened into a hurricane and was quickly intensifying when it struck the French overseas region of Guadeloupe on September 27. After entering the Caribbean, Inez briefly weakened before restrengthening, attaining peak sustained winds of 150 mph (240 km/h) on September 28. Continuing westward, Inez made landfall on the Barahona Peninsula of the Dominican Republic. Inez then struck southwestern Haiti,[7] where it was considered the worst hurricane since the 1920s.[26] Inez weakened quickly over Hispaniola, although it reintensified into a major hurricane before striking southeastern Cuba on September 30. The hurricane moved slowly over Cuba for two days before emerging into the Atlantic Ocean near the Bahamas. Inez stalled and later resumed its previous westward path. Between October 4 and October 5, the storm moved west-southwestward across the Florida Keys. Entering the Gulf of Mexico, Inez began to slowly re-strengthen. On October 10, Inez made landfall near Tampico as a Category 3 hurricane. The storm weakened rapidly and dissipated over Guanajuato on October 11.[7]

In Guadeloupe, Inez severely damaged the island's banana and sugar crops, and thousands of homes were damaged, leaving 10,000 people homeless.[27] There were 40 deaths and damage totaled approximately $50 million.[6][26] The storm flooded many rivers and destroyed over 800 houses in Dominican Republic.[28] There were about 100 deaths and $12 million in damage.[6] In Haiti, as many as 1,000 people were killed, and 60,000 people were left homeless. Damage totaled $20.35 million.[29] About 125,000 people were forced to evacuate in Cuba,[30] and there were three deaths and $20 million in damage.[6] In the Bahamas, heavy rainfall and high tides caused flooding, which killed five people and left $15.5 million in damage.[6] Hurricane-force winds were observed in the Florida Keys, where 160 homes and 190 trailers were damaged.[31] Salt spray damaged crops in the region, and there was $5 million in damage and four deaths.[6][32] In the Straits of Florida, Inez capsized a boat of Cuban refugees, killing 45 people.[6] In the northern Gulf of Mexico, a helicopter crashed after carrying evacuees from an oil rig, killing 11 people.[33] Inez produced flooding and caused some power outages in the Yucatán Peninsula.[34] At its final landfall, Inez flooded portions of Tamaulipas and cut off roads to Tampico.[35] About 84,000 people were left homeless,[36] and the hurricane destroyed at least 2,500 houses.[37] Damage was estimated at $104 million,[38] and there were 74 deaths in Mexico.[36]

Tropical Storm Judith

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 27 – September 30 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min); 1007 mbar (hPa) |

On September 26 and September 27, satellite imagery and ships monitored an area of disturbed weather located to the east of the Lesser Antilles and following Hurricane Inez. Based on reports of a circulation,[6] the system developed into a tropical depression at 00:00 UTC on September 27. The depression intensified slowly and became Tropical Storm Judith around midday on September 28. While centered north of Barbados the next day, Judith attained its peak intensity with maximum sustained winds of 50 mph (85 km/h) and a minimum barometric pressure of 1,007 mbar (29.7 inHg),[7] both of which were observed by a reconnaissance aircraft flight.[6] Shortly thereafter, the storm crossed through the Windward Islands and weakened to a tropical depression, possibly due to entering the outflow of Inez. At 12:00 UTC on September 30, Judith dissipated over the eastern Caribbean Sea.[7] Winds up to 37 mph (60 km/h) were observed on Martinique.[6]

Hurricane Lois

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | November 4 – November 11 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 80 mph (130 km/h) (1-min); 986 mbar (hPa) |

A vortex within an area of low pressure developed into a tropical depression at 12:00 UTC on November 4, while located about 965 mi (1,555 km) east-southeast of Bermuda. Initially, the depression featured cold temperatures near the center and did not completely possess tropical characteristics.[6][7] During the next few days, the depression organized further and acquired a warmer center of circulation while heading west-southwestward and then to the east-southeast.[6][7] Late on November 6, the depression was upgraded to Tropical Storm Lois,[7] based on reconnaissance aircraft flight observations.[6] assing west of the Azores on November 10, a sustained wind speed of 50 mph (80 km/h) was observed on Corvo Island. Moving over colder ocean temperature,[6] Lois gradually lost tropical characteristics and transitioned into an extratropical cyclone at 00:00 UTC on November 12, while located about 640 mi (1,030 km) north of São Miguel Island. The remnants curved southeastward and weakened until dissipating a few hundred miles offshore Portugal on November 14.[7]

Other systems

On October 9, a cyclone 200 mi (320 km) north of Cape Verde was named Kendra and operationally classified as a tropical storm, but post-analysis found the system actually remained an extratropical gale center. This makes Kendra the only system in the Atlantic basin to be named and not considered a tropical cyclone (pending reanalysis);[6] previously, another such system was Mike of 1950, but that storm was later re-added into the database as a tropical storm after reanalysis.[7]

In addition to the 11 tropical cyclones and Kendra, the Monthly Weather Review indicates the existence of two tropical depressions,[6] though neither are included in the Atlantic basin best track.[7] The first such system reportedly developed in the northwestern Caribbean Sea on June 28. The depression moved slowly northward and remained poorly defined throughout its duration, with a few radar reports indicating no evidence of an eye formation. Despite this, the wind field was described as well organized, especially in the northeastern quadrant. During the next four days, the depression crossed Cuba and later made landfall near Cross City, Florida. After striking Florida, the system curved northeastward and soon dissipated over southeastern Georgia on July 2. The depression spawned two tornadoes, one of which destroyed two aircraft at Palm Beach International Airport; the other touched down in Vero Beach and caused minimal effects. The depression dropped heavy rainfall in some areas of Florida, with a peak total of 10 in (250 mm) in Everglade City and Jacksonville. The precipitation in Jacksonville resulted in $50,000 in damage to roadways. Additionally, the depression brought "beneficial rains" to South Carolina.[6]

The other tropical depression was reported to have existed in late July. A tropical low pressure area moved across Florida and entered the northeastern Gulf of Mexico on July 24. By the following day, coastal radars indicated a relatively well-defined circulation. As a result, it is estimated that the system became a tropical depression later on July 25. After minimal intensification, the depression made landfall near Boothville, Louisiana early on July 26. The depression then curved westward and dissipated on the next day. Other than heavy thunderstorms and a brief suspension of fishing activities, no other effects were reported.[6]

Storm names

The following names were used for named storms (tropical storms and hurricanes) that formed in the North Atlantic in 1966.[39] Storms were named Dorothy, Faith, Hallie, Inez, Kendra and Lois for the first time in 1966. At the 1967 hurricane warning conference it was decided to use 1966's list of names for 1970, with the name Faith was substituted for Francelia.[40] The name Inez was retired after the 1969 hurricane warning conference, despite not having a significant effect on the United States.[41] Names that were not assigned are marked in gray.

|

|

See also

Notes

- ^ All damage figures are in 1966 USD, unless otherwise noted

- ^ A major hurricane is a storm that ranks as Category 3 or higher on the Saffir-Simpson hurricane wind scale.[4]

References

- ^ Neal Dorst; Sandy Delgado (May 20, 2011). Subject: E7) What is the farthest a tropical cyclone has traveled?. Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved February 14, 2013.

- ^ a b "Alice Was First Girl Storm". Tampa Bay Times. June 30, 1966. Retrieved May 25, 2014.

- ^ Russell Pfost; Pablo Santos (August 15, 2013). "History of the National Weather Service Forecast Office Miami, Florida". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved August 27, 2016.

- ^ Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale. National Hurricane Center (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. May 23, 2013. Retrieved May 25, 2014.

- ^ Tropical Cyclone Climatology. National Hurricane Center (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. March 19, 2014. Retrieved May 30, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay Arnold L. Sugg (March 1967). The Hurricane Season of 1966 (PDF). National Hurricane Center; Weather Bureau (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved May 24, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at "Atlantic hurricane best track (HURDAT version 2)" (Database). United States National Hurricane Center. April 5, 2023. Retrieved November 10, 2024.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Arnold L. Sugg (March 1967). The Hurricane Season of 1966 (PDF). National Hurricane Center; Weather Bureau (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved May 24, 2014.

- "45 Dead in Hurricane Wake". Spokane Daily Chronicle. St. Petersburg, Florida. Associated Press. June 9, 1966. Retrieved May 21, 2014.

- "Ferry Boat Captain Credits Luck". Edmonton Journal. Associated Press. September 8, 1966. p. 41. Retrieved May 24, 2014.

- "Inez Gains Power, Spawns Tornado on Way to Florida". Lodi News-Sentinel. United Press International. October 3, 1966. Retrieved May 24, 2014.

- "Inez Hurt Haiti". The Calgary Herald. Austin, Texas. Reuters. December 1, 1966. Retrieved May 24, 2014.

- "Inez Roils Gulf After Pounding Florida Keys". Toledo Blade. New York City, New York. Associated Press. October 5, 1966. Retrieved May 24, 2014.

- "Helicopter Crashes, 11 Killed". Star-News. Morgan City, Louisiana. United Press International. October 10, 1966. Retrieved May 24, 2014.

- "Inez Destruction Estimates Mount". The Palm Beach Post. Tampico, Tamaulipas. United Press International. October 13, 1966. Retrieved May 24, 2014.

- "U.S. Planes Aid Victims of Hurricane". Gettysburg Times. Tampico, Tamaulipas. Associated Press. October 15, 1966. Retrieved May 24, 2014.

- ^ Monthly Tropical Weather Summary. National Hurricane Center (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. September 1, 2013. Retrieved May 25, 2014.

- ^ Monthly Tropical Weather Summary. National Hurricane Center (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. November 2013. Retrieved May 25, 2014.

- ^ Atlantic basin Comparison of Original and Revised HURDAT. Hurricane Research Division; Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (Report). Miami, Florida: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. March 2011. Retrieved March 6, 2012.

- ^ David Levinson (August 20, 2008). 2005 Atlantic Ocean Tropical Cyclones. National Climatic Data Center (Report). Asheville, North Carolina: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on December 1, 2005. Retrieved March 6, 2012.

{{cite report}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ William Tucker (June 7, 1966). "Alma Whips Isle of Pines". The Miami News. Retrieved May 21, 2014.

- ^ "Hurricane Alma Gales Kill One Cuban; Alert Spreads Across Island". The Lewiston Daily Sun. Miami, Florida. Associated Press. June 8, 1966. Retrieved May 21, 2014.

- ^ "Cuba Enlists 100,000 for Alma Repair Job". The Miami News. Washington, D.C. North American Newspaper Alliance. June 18, 1966. Retrieved May 21, 2014.

- ^ a b "45 Dead in Hurricane Wake". Spokane Daily Chronicle. St. Petersburg, Florida. Associated Press. June 9, 1966. Retrieved May 21, 2014.

- ^ "Hurricane Alma Aims Winds, Tides Toward Florida's Tampa Bay Area". St. Petersburg Times. June 9, 1966. Retrieved May 21, 2014.

- ^ "Alma Lashes St. Petersburg". Daytona Beach Morning Journal. Cape Kennedy, Florida. Associated Press. June 9, 1966. Retrieved May 21, 2014.

- ^ "Tired Hurricane Spills Heavy Rain on Georgia". Toledo Blade. Associated Press. June 9, 1966. Retrieved May 21, 2014.

- ^ 1966-Celia (Report). Moncton, New Brunswick: Environment Canada. September 14, 2010. Retrieved May 24, 2014.

- ^ a b Carl O. Erickson (March 1967). Some Aspects Of The Development Of Hurricane Dorothy (PDF) (Report). Washington, D.C.: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved May 30, 2014.

- ^ C. B. Daniel; R. Maharaj; G. De Souza (May 2001). Tropical Cyclone Affecting Trinidad and Tobago 1725 to 2000 (PDF) (Report). Trinidad and Tobago Meteorological Service. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 23, 2005. Retrieved February 14, 2013.

- ^ Hurricane history (b) 1963-present that affected Bermuda (Report). Bermuda Climate and Weather. May 24, 2014.

- ^ "Ferry Boat Captain Credits Luck". Edmonton Journal. Associated Press. September 8, 1966. p. 41. Retrieved May 24, 2014.

- ^ Lars Andreas Roald (2008). Rainfall Floods and Weather Patterns (PDF) (Report). Norwegian Water Resources and Energy Directorate. pp. 31 and 34. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 5, 2013. Retrieved February 14, 2013.

{{cite report}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Inez Gains Power, Spawns Tornado on Way to Florida". Lodi News-Sentinel. United Press International. October 3, 1966. Retrieved May 24, 2014.

- ^ "Weaker Hurricane Inez Aims Winds at Eastern Cuba". St. Petersburg Times. September 30, 1966. Retrieved May 24, 2014.

- ^ "Inez Again Threatens Florida and Gulf Coast". The Victoria Advocate. Miami, Florida. October 1, 1966. Retrieved May 24, 2014.

- ^ "Inez Hurt Haiti". The Calgary Herald. Austin, Texas. Reuters. December 1, 1966. Retrieved May 24, 2014.

- ^ "Weakened Storm Hovers Off Cuba". Spokane Daily Chronicle. Miami, Florida. United Press International. October 1, 1966. Retrieved May 24, 2014.

- ^ "Hurricane Inez Lumbering Toward Mexico". The Milwaukee Sentinel. Miami, Florida. Associated Press. October 7, 1966. Retrieved May 24, 2014.

- ^ "Inez Roils Gulf After Pounding Florida Keys". Toledo Blade. New York City, New York. Associated Press. October 5, 1966. Retrieved May 24, 2014.

- ^ "Helicopter Crashes, 11 Killed". Star-News. Morgan City, Louisiana. United Press International. October 10, 1966. Retrieved May 24, 2014.

- ^ "Hurricane Aims for Mexico's Eastern Coast". Lewiston Evening Journal. Mexico City, Mexico. Associated Press. October 8, 1966. Retrieved May 24, 2014.

- ^ "Hurricane Inez Moves Across Mexican Coast". The Montreal Gazette. Mexico City, Mexico. Reuters. October 11, 1966. Retrieved February 24, 2013.

- ^ a b "U.S. Planes Aid Victims of Hurricane". Gettysburg Times. Tampico, Tamaulipas. Associated Press. October 15, 1966. Retrieved May 24, 2014.

- ^ "15 Die as Mercy Launch Sinks". Sarasota Journal. Ciudad Victoria, Tamaulipas. United Press International. October 13, 1966. Retrieved February 23, 2013.

- ^ "Inez Destruction Estimates Mount". The Palm Beach Post. Tampico, Tamaulipas. United Press International. October 13, 1966. Retrieved May 24, 2014.

- ^ "Names set for '66 hurricanes". Washington Afro-American. Miami, Florida. United Press International. May 31, 1966. Retrieved May 25, 2014.

- ^ http://www.aoml.noaa.gov/general/lib/lib1/nhclib/Publications/HurWarningConf/HurWarningconf1967.pdf

- ^ http://www.aoml.noaa.gov/general/lib/lib1/nhclib/Publications/HOP%27s/HurWarningConf1969-.pdf