Fort Ticonderoga

Fort Ticonderoga | |

Fort Ticonderoga from Mount Defiance | |

| Location | Ticonderoga, New York |

|---|---|

| Nearest city | Burlington, Vermont |

| Coordinates | 43°50′30″N 73°23′15″W / 43.84167°N 73.38750°W |

| Area | 21,950 acres (34.3 sq mi; 88.8 km2) |

| Built | 1755–1758 |

| Architect | Marquis de Lotbinière |

| Architectural style | Vauban-style fortress |

| NRHP reference No. | 66000519 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | October 15, 1966[1] |

| Designated NHL | October 9, 1960[2] |

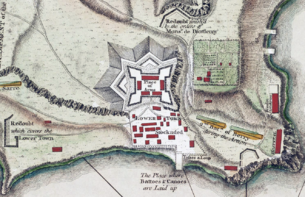

Fort Ticonderoga (/taɪkɒndəˈroʊɡə/), formerly Fort Carillon, is a large 18th-century star fort built by the French at a narrows near the south end of Lake Champlain, in northern New York, in the United States. It was constructed by Canadian-born French military engineer Michel Chartier de Lotbinière, Marquis de Lotbinière between October 1755 and 1757, during the action in the "North American theater" of the Seven Years' War, often referred to in the US as the French and Indian War. The fort was of strategic importance during the 18th-century colonial conflicts between Great Britain and France, and again played an important role during the Revolutionary War.

The site controlled a river portage alongside the mouth of the rapids-infested La Chute River, in the 3.5 miles (5.6 km) between Lake Champlain and Lake George. It was thus strategically placed for the competition over trade routes between the British-controlled Hudson River Valley and the French-controlled Saint Lawrence River Valley.

The terrain amplified the importance of the site. Both lakes were long and narrow and oriented north–south, as were the many ridge lines of the Appalachian Mountains, which extended as far south as Georgia. The mountains created nearly impassable terrains to the east and west of the Great Appalachian Valley that the site commanded.

The name "Ticonderoga" comes from the Iroquois word tekontaró:ken, meaning "it is at the junction of two waterways".[3]

During the 1758 Battle of Carillon, 4,000 French defenders were able to repel an attack by 16,000 British troops near the fort. In 1759, the British returned and drove a token French garrison from the fort. During the Revolutionary War, when the British controlled the fort, it was attacked on May 10, 1775, in the Capture of Fort Ticonderoga by the Green Mountain Boys and other state militia under the command of Ethan Allen and Benedict Arnold, who captured it in the surprise attack. Cannons taken from the fort were transported to Boston to lift its siege by the British, who evacuated the city in March 1776. The Americans held the fort until June 1777, when British forces under General John Burgoyne occupied high ground above it; the threat resulted in the Continental Army troops being withdrawn from the fort and its surrounding defenses. The only direct attack on the fort during the Revolution took place in September 1777, when John Brown led 500 Americans in an unsuccessful attempt to capture the fort from about 100 British defenders.

The British abandoned the fort after the failure of the Saratoga campaign, and it ceased to be of military value after 1781. After gaining independence, the United States allowed the fort to fall into ruin; local residents stripped it of much of its usable materials. Purchased by a private family in 1820, it became a stop on tourist routes of the area. Early in the 20th century, its private owners restored the fort. A foundation now operates the fort as a tourist attraction, museum, and research center.

Geography and early history

Lake Champlain, which forms part of the border between New York and Vermont, and the Hudson River together formed an important travel route that was used by Indians long before the arrival of European colonists. The route was relatively free of obstacles to navigation, with only a few portages. One strategically important place on the route lies at a narrows near the southern end of Lake Champlain, where Ticonderoga Creek, known in colonial times as the La Chute River, because it was named by French colonists, enters the lake, carrying water from Lake George. Although the site provides commanding views of the southern extent of Lake Champlain, Mount Defiance, at 853 ft (260 m), and two other hills (Mount Hope and Mount Independence) overlook the area.[4]

Indians had occupied the area for centuries before French explorer Samuel de Champlain first arrived there in 1609. Champlain recounted that the Algonquins, with whom he was traveling, battled a group of Iroquois nearby.[5] In 1642, French missionary Isaac Jogues was the first white man to traverse the portage at Ticonderoga while escaping a battle between the Iroquois and members of the Huron tribe.[6]

The French, who had colonized the Saint Lawrence River valley to the north, and the English, who had taken over the Dutch settlements that became the Province of New York to the south, began contesting the area as early as 1691, when Pieter Schuyler built a small wooden fort at the Ticonderoga point on the western shore of the lake.[7] These colonial conflicts reached their height in the French and Indian War, which began in 1754 as the North American front of the Seven Years' War.[8]

Construction

In 1755, following the Battle of Lake George, the French decided to construct a fort here. Marquis de Vaudreuil, the governor of the French Province of Canada, sent his cousin Michel Chartier de Lotbinière to design and construct a fortification at this militarily important site, which the French called Fort Carillon.[9] The name "Carillon" has variously been attributed to the name of a former French officer, Philippe de Carrion du Fresnoy, who established a trading post at the site in the late 17th century,[10] or (more commonly) to the sounds made by the rapids of the La Chute River, which were said to resemble the chiming bells of a carillon.[11] Construction on the star-shaped fort, which Lotbinière based on designs of the renowned French military engineer Vauban, began in October 1755 and then proceeded slowly during the warmer-weather months of 1756 and 1757, using troops stationed at nearby Fort St. Frédéric and from Canada.[12][13]

The work in 1755 consisted primarily of beginning construction on the main walls and on the Lotbinière redoubt, an outwork to the west of the site that provided additional coverage of the La Chute River. During the next year, the four main bastions were built, as well as a sawmill on the La Chute. Work slowed in 1757, when many of the troops prepared for and participated in the attack on Fort William Henry. The barracks and demi-lunes were not completed until spring 1758.[14]

Walls and bastions

The French built the fort to control the south end of Lake Champlain and prevent the British from gaining military access to the lake. Consequently, its most important defenses, the Reine and Germaine bastions, were directed to the northeast and northwest, away from the lake, with two demi-lunes further extending the works on the land side. The Joannes and Languedoc bastions overlooked the lake to the south, providing cover for the landing area outside the fort. The walls were seven feet (2.1 m) high and fourteen feet (4.3 m) thick, and the whole works was surrounded by a glacis and a dry moat five feet (1.5 m) deep and fifteen feet (4.6 m) wide. When the walls were first erected in 1756, they were made of squared wooden timbers, with earth filling the gap. The French then began to dress the walls with stone from a quarry about one mile (1.6 km) away, although this work was never fully completed.[11] When the main defenses became ready for use, the fort was armed with cannons hauled from Montreal and Fort St. Frédéric.[15][16]

Inside and outside

The fort contained three barracks and four storehouses. One bastion held a bakery capable of producing 60 loaves of bread a day. A powder magazine was hacked out of the bedrock beneath the Joannes bastion. All the construction within the fort was of stone.[11]

A wooden palisade protected an area outside the fort between the southern wall and the lake shore. This area contained the main landing for the fort and additional storage facilities and other works necessary for maintenance of the fort.[11] When it became apparent in 1756 that the fort was too far to the west of the lake, the French constructed an additional redoubt to the east to enable cannon to cover the lake's narrows.[17]

-

Officers' barracks, right; soldiers' barracks, left

-

Inside the first wall; officers' barracks at left, soldiers' barracks at right

-

Store room and powder magazine (now Mars Education Center); soldiers' barracks at right

-

Front of the fort

-

View of the lake from the front

-

Back view of the fort

Analysis

By 1758, the fort was largely complete; the only ongoing work thereafter consisted of dressing the walls with stone. Still, General Montcalm and two of his military engineers surveyed the works in 1758 and found something to criticize in almost every aspect of the fort's construction; the buildings were too tall and thus easier for attackers' cannon fire to hit, the powder magazine leaked, and the masonry was of poor quality.[18] The critics apparently failed to notice the fort's significant strategic weakness: several nearby hills overlooked the fort and made it possible for besiegers to fire down on the defenders from above.[19] Lotbinière, who may have won the job of building the fort only because he was related to Governor Vaudreuil, had lost a bid to become Canada's chief engineer to Nicolas Sarrebource de Pontleroy, one of the two surveying engineers, in 1756, all of which may explain the highly negative report. Lotbinière's career suffered for years afterwards.[20]

William Nester, in his exhaustive analysis of the Battle of Carillon, notes additional problems with the fort's construction. The fort was small for a Vauban-style fort, about 500 feet (150 m) wide, with a barracks capable of holding only 400 soldiers. Storage space inside the fort was similarly limited, requiring the storage of provisions outside the fort's walls in exposed places. Its cistern was small, and the water quality was supposedly poor.[21][22]

Military history

French and Indian War

In August 1757, the French captured Fort William Henry in an action launched from Fort Carillon.[23] This, and a string of other French victories in 1757, prompted the British to organize a large-scale attack on the fort as part of a multi-campaign strategy against French Canada.[24] In June 1758, British General James Abercromby began amassing a large force at Fort William Henry in preparation for the military campaign directed up the Champlain Valley. These forces landed at the north end of Lake George, only four miles from the fort, on July 6.[25] The French general Louis-Joseph de Montcalm, who had only arrived at Carillon in late June, engaged his troops in a flurry of work to improve the fort's outer defenses. They built, over two days, entrenchments around a rise between the fort and Mount Hope, about three-quarters of a mile (one kilometer) northwest of the fort, and then constructed an abatis (felled trees with sharpened branches pointing out) below these entrenchments.[26] They conducted the work unimpeded by military action, as Abercromby failed to advance directly to the fort on July 7. Abercromby's second-in-command, Brigadier General George Howe, had been killed when his column encountered a French reconnaissance troop. Abercromby "felt [Howe's death] most heavily" and may have been unwilling to act immediately.[27]

On July 8, 1758, Abercromby ordered a frontal attack against the hastily assembled French works. Abercromby tried to move rapidly against the few French defenders, opting to forgo field cannon and relying instead on the numerical superiority of his 16,000 troops. In the Battle of Carillon, the British were soundly defeated by the 4,000 French defenders.[28] The battle took place far enough away from the fort that its guns were rarely used.[29] The battle gave the fort a reputation for impregnability, which affected future military operations in the area, notably during the American Revolutionary War.[30] Following the French victory, Montcalm, anticipating further British attacks, ordered additional work on the defenses, including the construction of the Germain and Pontleroy redoubts (named for the engineers under whose direction they were constructed) to the northeast of the fort.[31][32] However, the British did not attack again in 1758, so the French withdrew all but a small garrison of men for the winter in November.[33]

The British under General Jeffery Amherst captured the fort the following year in the 1759 Battle of Ticonderoga. In this confrontation 11,000 British troops, using emplaced artillery, drove off the token garrison of 400 Frenchmen. The French, in withdrawing, used explosives to destroy what they could of the fort[34] and spiked or dumped cannons that they did not take with them. Although the British worked in 1759 and 1760 to repair and improve the fort,[35] it was not part of any further significant action in the war. After the war, the British garrisoned the fort with a small number of troops and allowed it to fall into disrepair. Colonel Frederick Haldimand, in command of the fort in 1773, wrote that it was in "ruinous condition".[36]

Early Revolutionary War

In 1775, Fort Ticonderoga, in disrepair, was still manned by a token British force. They found it extremely useful as a supply and communication link between Canada (which they had taken over after their victory in the Seven Years' War) and New York.[37] On May 10, 1775, less than one month after the Revolutionary War was ignited with the battles of Lexington and Concord, the British garrison of 48 soldiers was surprised by a small force of Green Mountain Boys, along with militia volunteers from Massachusetts and Connecticut, led by Ethan Allen and Benedict Arnold.[38] Allen claims to have said, "Come out you old Rat!" to the fort's commander, Captain William Delaplace.[39] He also later said that he demanded that the British commander surrender the fort "In the name of the Great Jehovah and the Continental Congress!"; however, his surrender demand was made to Lieutenant Jocelyn Feltham and not the fort's commander, who did later appear and surrender his sword.[39]

With the capture of the fort, the Patriot forces obtained a large supply of cannons and other armaments, much of which Henry Knox transported to Boston during the winter of 1775–1776. Ticonderoga's cannons were instrumental in ending the Siege of Boston when they were used to fortify Dorchester Heights.[40] With Dorchester Heights secured by the Patriots, the British were forced to evacuate the city in March 1776.[37] The capture of Fort Ticonderoga by the Patriots made communication between the British Canadian and American commands much more difficult.

Benedict Arnold remained in control of the fort until 1,000 Connecticut troops under the command of Benjamin Hinman arrived in June 1775. Because of a series of political maneuvers and miscommunications, Arnold was never notified that Hinman was to take command. After a delegation from Massachusetts (which had issued Arnold's commission) arrived to clarify the matter, Arnold resigned his commission and departed, leaving the fort in Hinman's hands.[41]

Beginning in July 1775, Ticonderoga was used as a staging area for the invasion of Quebec, planned to begin in September. Under the leadership of generals Philip Schuyler and Richard Montgomery, men and materiel for the invasion were accumulated there through July and August.[42] On August 28, after receiving word that British forces at Fort Saint-Jean, not far from the New York–Quebec border, were nearing completion of boats to launch onto Lake Champlain, Montgomery launched the invasion, leading 1,200 troops down the lake.[43] Ticonderoga continued to serve as a staging base for the action in Quebec until the battle and siege at Quebec City that resulted in Montgomery's death.[44]

In May 1776, British troops began to arrive at Quebec City, where they broke the Continental Army's siege.[45] The British chased the American forces back to Ticonderoga in June and, after several months of shipbuilding, moved down Lake Champlain under Guy Carleton in October. The British destroyed a small fleet of American gunboats in the Battle of Valcour Island in mid-October, but snow was already falling, so the British retreated to winter quarters in Quebec. About 1,700 troops from the Continental Army, under the command of Colonel Anthony Wayne, wintered at Ticonderoga.[44][46] The British offensive resumed the next year in the Saratoga campaign under General John Burgoyne.[47]

Saratoga campaign

During the summer of 1776, the Americans, under the direction of General Schuyler, and later under General Horatio Gates, added substantial defensive works to the area. Mount Independence, which is almost completely surrounded by water, was fortified with trenches near the water, a horseshoe battery part way up the side, a citadel at the summit, and redoubts armed with cannons surrounding the summit area. These defenses were linked to Ticonderoga with a pontoon bridge that was protected by land batteries on both sides. The works on Mount Hope, the heights above the site of Montcalm's victory, were improved to include a star-shaped fort. Mount Defiance remained unfortified.[48]

In March 1777, American generals were strategizing about possible British military movements and considered an attempt on the Hudson River corridor a likely possibility. General Schuyler, heading the forces stationed at Ticonderoga, requested 10,000 troops to guard Ticonderoga and 2,000 to guard the Mohawk River valley against British invasion from the north. George Washington, who had never been to Ticonderoga (his only visit was to be in 1783),[49] believed that an overland attack from the north was unlikely, because of the alleged impregnability of Ticonderoga.[30] This, combined with continuing incursions up the Hudson River valley by British forces occupying New York City, led Washington to believe that any attack on the Albany area would be from the south, which, as it was part of the supply line to Ticonderoga, would necessitate a withdrawal from the fort. As a result, no significant actions were taken to further fortify Ticonderoga or significantly increase its garrison.[50] The garrison, about 2,000 men under General Arthur St. Clair, was too small to man all the defenses.[51]

General Gates, who oversaw the northern defenses, was aware that Mount Defiance threatened the fort.[52] John Trumbull had pointed this out as early as 1776, when a shot fired from the fort was able to reach Defiance's summit, and several officers inspecting the hill noted that there were approaches to its summit where gun carriages could be pulled up the sides.[52] As the garrison was too small to properly defend all the existing works in area, Mount Defiance was left undefended.[53] Anthony Wayne left Ticonderoga in April 1777 to join Washington's army; he reported to Washington that "all was well", and that the fort "can never be carried, without much loss of blood".[54]

"Where a goat can go, a man can go; and where a man can go, he can drag a gun."

General Burgoyne led 7,800 British and Hessian forces south from Quebec in June 1777.[55] After occupying nearby Fort Crown Point without opposition on June 30, he prepared to besiege Ticonderoga.[56] Burgoyne realized the tactical advantage of the high ground, and had his troops haul cannons to the top of Mount Defiance. Faced with bombardment from the heights (although no shots had yet been fired), General St. Clair ordered Ticonderoga abandoned on July 5, 1777. Burgoyne's troops moved in the next day,[57] with advance guards pursuing the retreating Patriot Americans.[58] Washington, on hearing of Burgoyne's advance and the retreat from Ticonderoga, stated that the event was "not apprehended, nor within the compass of my reasoning".[59] News of the abandonment of the "Impregnable Bastion" without a fight, caused "the greatest surprise and alarm" throughout the colonies.[60] After public outcry over his actions, General St. Clair was court-martialed in 1778. He was cleared on all charges.[59]

One last attack

Following the British capture of Ticonderoga, it and the surrounding defenses were garrisoned by 700 British and Hessian troops under the command of Brigadier General Henry Watson Powell. Most of these forces were on Mount Independence, with only 100 each at Fort Ticonderoga and a blockhouse they were constructing on top of Mount Defiance.[61] George Washington sent General Benjamin Lincoln into Vermont to "divide and distract the enemy".[62] Aware that the British were housing American prisoners in the area, Lincoln decided to test the British defenses. On September 13, he sent 500 men to Skenesboro, which they found the British had abandoned, and 500 each against the defenses on either side of the lake at Ticonderoga. Colonel John Brown led the troops on the west side, with instructions to release prisoners if possible, and attack the fort if it seemed feasible.[63]

Early on September 18, Brown's troops surprised a British contingent holding some prisoners near the Lake George landing, while a detachment of his troops sneaked up Mount Defiance, and captured most of the sleeping construction crew. Brown and his men then moved down the portage trail toward the fort, surprising more troops and releasing prisoners along the way.[64] The fort's occupants were unaware of the action until Brown's men and British troops occupying the old French lines skirmished. At this point Brown's men dragged two captured six-pound guns up to the lines, and began firing on the fort. The men who had captured Mount Defiance began firing a twelve-pounder from that site.[65] The column that was to attack Mount Independence was delayed, and its numerous defenders were alerted to the action at the fort below before the attack on their position began. Their musket fire, as well as grapeshot fired from ships anchored nearby, intimidated the Americans sufficiently that they never launched an assault on the defensive positions on Mount Independence.[65] A stalemate persisted, with regular exchanges of cannon fire, until September 21, when 100 Hessians, returning from the Mohawk Valley to support Burgoyne, arrived on the scene to provide reinforcement to the besieged fort.[66] Brown eventually sent a truce party to the fort to open negotiations; the party was fired on, and three of its five members were killed.[67] Brown, realizing that the weaponry they had was insufficient to take the fort, decided to withdraw. Destroying many bateaux and seizing a ship on Lake George, he set off to annoy British positions on that lake.[67] His action resulted in the freeing of 118 Americans and the capture of 293 British troops, while suffering fewer than ten casualties.[65]

Abandonment

Following Burgoyne's defeat at Saratoga, the fort at Ticonderoga became increasingly irrelevant. The British abandoned it and nearby Fort Crown Point in November 1777, destroying both as best they could prior to their withdrawal.[68] The fort was occasionally reoccupied by British raiding parties in the following years, but it no longer held a prominent strategic role in the war. It was finally abandoned by the British for good in 1781, following their surrender at Yorktown.[69] In the years following the war, area residents stripped the fort of usable building materials, even melting some of the cannons down for their metal .[70]

Tourist attraction

In 1785, the fort's lands became the property of the state of New York. The state donated the property to Columbia and Union colleges in 1803.[71] The colleges sold the property to William Ferris Pell in 1820.[72]

Pell first used the property as a summer retreat. Completion of railroads and canals connecting the area to New York City brought tourists to the area,[73] so he converted his summer house, known as The Pavilion, into a hotel to serve the tourist trade. In 1848, the Hudson River School artist Russell Smith painted Ruins of Fort Ticonderoga, depicting the condition of the fort.[74]

The Pell family, a politically important clan with influence throughout American history (from William C. C. Claiborne, the first Governor of Louisiana, to a Senator from Rhode Island, Claiborne Pell), hired English architect Alfred Bossom to restore the fort and formally opened it to the public in 1909 as an historic site. The ceremonies, which commemorated the 300th anniversary of the discovery of Lake Champlain by European explorers, were attended by President William Howard Taft.[75] Stephen Hyatt Pell, who spearheaded the restoration effort, founded the Fort Ticonderoga Association in 1931, which is now responsible for the fort.[76] Funding for the restoration also came from Robert M. Thompson, father of Stephen Pell's wife, Sarah Gibbs Thompson.[77]

Between 1900 and 1950, the foundation acquired the historically important lands around the fort, including Mount Defiance, Mount Independence, and much of Mount Hope.[78] The fort was rearmed with fourteen 24-pound cannons provided by the British government. These cannons had been cast in England for use during the American Revolution, but the war ended before they were shipped over.[79]

Designated as a National Historic Landmark by the Department of Interior, the fort is now operated by the foundation as a tourist attraction, early American military museum, and research center. The fort opens annually around May 10, the anniversary of the 1775 capture, and closes in late October.[80]

The fort has been on a watchlist of National Historic Landmarks since 1998, because of the poor condition of some of the walls and of the 19th-century pavilion constructed by William Ferris Pell.[2] The pavilion was being restored in 2009. In 2008, the powder magazine, destroyed by the French in 1759, was reconstructed by Tonetti Associates Architects,[81] based in part on the original 1755 plans.[82] Also in 2008, the withdrawal of a major backer's financial support forced the museum, which was facing significant budget deficits, to consider selling one of its major art works, Thomas Cole's Gelyna, View near Ticonderoga. However, fundraising activities were successful enough to prevent the sale.[83]

The not-for-profit Living History Education Foundation conducts teacher programs at Fort Ticonderoga during the summer that last approximately one week. The program trains teachers how to teach Living History techniques, and to understand and interpret the importance of Fort Ticonderoga during the French and Indian War and the American Revolution.[84]

The fort conducts other seminars, symposia, and workshops throughout the year, including the annual War College of the Seven Years' War in May and the Seminar on the American Revolution in September.[85]

The Pell family estate is located north of the fort. In 1921, Sarah Pell undertook reconstruction of the gardens. She hired Marian Cruger Coffin, one of the most famous American landscape architects of the period. In 1995, the gardens were restored and later opened for public visiting; they are known as the King's Garden.[86]

Memorials

The U.S. Navy has given the name 'Ticonderoga' to five different vessels, as well as to entire classes of cruisers and aircraft carriers.[87][88]

The fort was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1960.[2] Included in the landmarked area are the fort, as well as Mount Independence and Mount Defiance.[89] It was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1966.[2] The Ticonderoga pencil, manufactured by the Dixon Ticonderoga Corporation, is named for the fort.[90]

See also

- Battle on Snowshoes (1757)

- Battle on Snowshoes (1758)

- List of French forts in North America

- Duncan Campbell (died 1758), Scottish officer of the British Army, subject of a legend about the fort

Notes

- ^ National Register Information System

- ^ a b c d NHL summary webpage

- ^ Afable, p. 193

- ^ Lonergan (1959), p. 2

- ^ Lonergan (1959), pp. 5–8

- ^ Lonergan (1959), pp. 9–10

- ^ Lonergan (1959), pp. 15,18

- ^ Anderson (2000), pp. 11–12

- ^ Lonergan (1959), p. 17

- ^ Ketchum, p. 29

- ^ a b c d Nester, p. 110

- ^ Lonergan (1959), p. 22

- ^ Stoetzel, p. 297

- ^ Lonergan (1959), pp. 19–25

- ^ Kaufmann, pp. 75–76

- ^ Lonergan (1959), p. 19

- ^ Chartrand, p. 36

- ^ Lonergan (1959), p. 25

- ^ Lonergan (1959), p. 26

- ^ Thorpe

- ^ Nester, p. 111

- ^ Ketchum, p. 28

- ^ Anderson (2005), pp. 109–115

- ^ Anderson (2005), p. 126

- ^ Anderson (2005), p. 132

- ^ Anderson (2000), p. 242

- ^ Anderson (2005), p. 135

- ^ Anderson (2005), pp. 135–138

- ^ Chartrand and Nester, who both wrote detailed accounts of the battle, describe only one brief time period during the battle when the cannons on the southwest bastion were fired at an attempted British maneuver on the river.

- ^ a b Furneaux, p. 51

- ^ ASHPS Annual Report 1913, p. 619

- ^ Stoetzel, p. 453

- ^ Atherton, p. 419

- ^ Lonergan (1959), p. 56

- ^ Kaufmann, pp. 90–91

- ^ Lonergan (1959), p. 59

- ^ a b Intelligence Throughout History: The Capture of Fort Ticonderoga, 1775

- ^ Martin, pp. 70–72

- ^ a b Martin, p. 71

- ^ Martin, p. 73

- ^ Martin, pp. 80–97

- ^ Smith, Vol 1, pp. 252–270

- ^ Smith (1907), Vol 1, p. 320

- ^ a b These events are recounted in detail in Smith (1907), Vol 2.

- ^ Smith (1907), Vol 2, p. 316

- ^ Hamilton, p. 165

- ^ Lonergan (1959), p. 101

- ^ Lonergan (1959), pp. 97–99

- ^ Lonergan (1959), p. 123

- ^ Furneaux, p. 52

- ^ Lonergan (1959), p. 99

- ^ a b Furneaux, pp. 54–55

- ^ Furneaux, p. 55

- ^ Furneaux, p. 58

- ^ Furneaux, p. 47

- ^ Furneaux, pp. 49, 57

- ^ Furneaux, pp. 65–67

- ^ Furneaux, p. 74

- ^ a b Furneaux, p. 88

- ^ Dr. James Thacher, quoted in Furneaux, p. 88

- ^ Hamilton, pp. 215–216

- ^ Hamilton, p. 216

- ^ Hamilton, p. 217

- ^ Hamilton, p. 218

- ^ a b c Hamilton, p. 219

- ^ Hamilton, p. 220

- ^ a b Hamilton, p. 222

- ^ Crego, p. 70

- ^ Lonergan (1959), p. 122

- ^ Pell, p. 91

- ^ Hamilton, p. 226

- ^ Crego, p. 76

- ^ Crego, p. 73

- ^ Crego, p. 75

- ^ Lonergan (1959), p. 124

- ^ Hamilton, p. 230

- ^ Crego, p. 6.

- ^ Lonergan (1959), pp. 125–127

- ^ Pell, pp. 108–109

- ^ Fort Hours

- ^ "Tonetti Associates Architects' Historic Reconstruction at Fort Ticonderoga", Traditional Building Magazine, October 2008

- ^ Foster

- ^ Albany Times Union, December 18, 2008

- ^ "Index". Livinghistoryed.org. Retrieved November 8, 2012.

- ^ "Workshops & Seminars". Fort Ticonderoga. Retrieved January 31, 2018.

- ^ "The King's Garden". Fort Ticonderoga. Archived from the original on June 28, 2013. Retrieved June 18, 2013.

- ^ Bauer, pp. 36, 65, 67, 118, 119, 217, 218

- ^ US Office of Naval Records, p. 106

- ^ Ashton

- ^ Dixon Ticonderoga Corporation

References

Fort history sources

- Chartrand, Rene (2008). The Forts of New France in Northeast America 1600–1763. New York: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84603-255-4. OCLC 191891156.

- Crego, Carl R. (2004). Fort Ticonderoga. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-3502-9. OCLC 56032864.

- Kaufmann, J. E.; Idzikowski, Tomasz (2004). Fortress America: The Forts that Defended America, 1600 to the Present. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-81294-1. OCLC 56912995.

- Hamilton, Edward (1964). Fort Ticonderoga, Key to a Continent. Boston: Little, Brown. OCLC 965281.

- Lonergan, Carroll Vincent (1959). Ticonderoga, Historic Portage. Ticonderoga, New York: Fort Mount Hope Society Press. OCLC 2000876.

- Pell, Stephen (1966). Fort Ticonderoga: A Short History. Ticonderoga, New York: Fort Ticonderoga Museum. OCLC 848305.

Battle history sources

- Anderson, Fred (2005). The War that made America. New York: Viking. ISBN 978-0-670-03454-3. OCLC 60671897.

- Anderson, Fred (2000). Crucible of War: The Seven Years' War and the Fate of Empire in British North America, 1754–1766. New York: Vintage Books. ISBN 978-0-375-70636-3. OCLC 253943947.

- Atherton, William Henry (1914). Montreal, 1535–1914, Under British Rule, Volume 1. Montreal: S. J. Clarke. OCLC 6683395.

- Furneaux, Rupert (1971). The Battle of Saratoga. New York: Stein and Day. ISBN 978-0-8128-1305-0. OCLC 134959.

- Ketchum, Richard M. (1999). Saratoga: Turning Point of America's Revolutionary War. New York: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-8050-6123-9. OCLC 41397623.

- Martin, James Kirby (1997). Benedict Arnold: Revolutionary Hero. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-5560-0. OCLC 36343341.

- Nester, William (2008). The Epic Battles of the Ticonderoga, 1758. Albany: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-7321-4. OCLC 105469157.

- Smith, Justin H (1907). Our Struggle for the Fourteenth Colony: Canada, and the American Revolution, Volume 1. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons. OCLC 259236.

- Smith, Justin H (1907). Our Struggle for the Fourteenth Colony: Canada, and the American Revolution, Volume 2. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons. OCLC 259236.

- Stoetzel, Donald I (2008). Encyclopedia of the French and Indian War in North America, 1754–1763. Westminster, Maryland: Heritage Books. ISBN 978-0-7884-4517-0. OCLC 243602289.

Other sources

- Afable, Patricia O.; Beeler, Madison S. (1996). "Place Names". In Goddard, Ives (ed.). Languages. Handbook of North American Indians. Vol. 17. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution. ISBN 978-0-16-048774-3. OCLC 43957746.

- American Scenic and Historic Preservation Society (1913). Annual Report, 1913. Albany, New York: J.B. Lyon. OCLC 1480703.

- Ashton, Charles H; Hunter, Richard W (August 1983). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination: Fort Ticonderoga / Mount Independence National Historic Landmark" (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved January 10, 2009. and Accompanying 40 photos, from 1983, 1967, and 1980. (13.5 MB)

- Bauer, Karl Jack; Roberts, Stephen S. (1991). Register of Ships of the U.S. Navy, 1775–1990: Major Combatants. New York: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-26202-9. OCLC 24010356.

- Foster, Margaret (July 3, 2008). "Fort Ticonderoga Rededicates Green Replica of Building Lost in 1759". Preservation magazine. National Trust for Historic Preservation. Retrieved February 9, 2009.

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. January 23, 2007.

- Nearing, Brian (December 18, 2008). "Fort Ticonderoga art sale scrapped". Albany Times Union.

- Polmar, Norman (2001). The Naval Institute Guide to the Ships and Aircraft of the U.S. Fleet (17 ed.). Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-656-6.

- Thorpe, F.J.; Nicolini-Maschino, Sylvette (1979). "Chartier de Lotbinière, Michel, Marquis de Lotbinière". In Halpenny, Francess G (ed.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. IV (1771–1800) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- United States Office of Naval Records (1920). German Submarine Activities on the Atlantic Coast of the United States and Canada. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. OCLC 50058251.

- "Dixon Ticonderoga". Dixon Ticonderoga Corporation. Retrieved April 1, 2009.

- "Fort Ticonderoga Hours and Rates". Fort Ticonderoga Association. Retrieved January 10, 2009.

- "NHL summary webpage for Fort Ticonderoga". National Park Service. Archived from the original on November 18, 2007. Retrieved September 13, 2007.

External links

- Official website

- Timeline 18th & 19th century

- Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) No. NY-3212, "Fort Ticonderoga, Fort Ticonderoga, Essex County, NY", 5 photos

- Fort Ticonderoga history at Historic Lakes

- Battle of Ticonderoga – 1758 at British Battles

- Capture of Ticonderoga at Thrilling Incidents in American History

- 1757 establishments in New France

- American Revolution on the National Register of Historic Places

- American Revolutionary War forts

- Buildings and structures in Essex County, New York

- Champlain Valley National Heritage Area

- Colonial forts in New York (state)

- Forts in New York (state)

- Forts on the National Register of Historic Places in New York (state)

- French and Indian War forts

- French forts in the United States

- Historic American Buildings Survey in New York (state)

- Living museums in New York (state)

- Military and war museums in New York (state)

- Military installations established in 1757

- Museums in Essex County, New York

- National Historic Landmarks in New York (state)

- National Register of Historic Places in Essex County, New York

- Star forts