Accounting

| Part of a series on |

| Accounting |

|---|

|

| Business administration |

|---|

| Management of a business |

Accounting or Accountancy is the measurement, processing, and communication of financial and non financial information about economic entities[1][2] such as businesses and corporations. Accounting, which has been called the "language of business",[3] measures the results of an organization's economic activities and conveys this information to a variety of users, including investors, creditors, management, and regulators.[4] Practitioners of accounting are known as accountants. The terms "accounting" and "financial reporting" are often used as synonyms.

Accounting can be divided into several fields including financial accounting, management accounting, external auditing, tax accounting and cost accounting.[5][6] Accounting information systems are designed to support accounting functions and related activities. Financial accounting focuses on the reporting of an organization's financial information, including the preparation of financial statements, to the external users of the information, such as investors, regulators and suppliers;[7] and management accounting focuses on the measurement, analysis and reporting of information for internal use by management.[1][7] The recording of financial transactions, so that summaries of the financials may be presented in financial reports, is known as bookkeeping, of which double-entry bookkeeping is the most common system.[8]

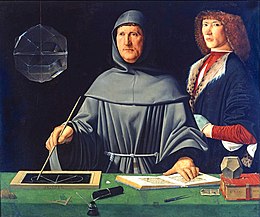

Accounting has existed in various forms and levels of sophistication throughout human history. The double-entry accounting system in use today was developed in medieval Europe, particularly in Venice, and is usually attributed to the Italian mathematician and Franciscan friar Luca Pacioli.[9] Today, accounting is facilitated by accounting organizations such as standard-setters, accounting firms and professional bodies. Financial statements are usually audited by accounting firms,[10] and are prepared in accordance with generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP).[7] GAAP is set by various standard-setting organizations such as the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) in the United States[1] and the Financial Reporting Council in the United Kingdom. As of 2012, "all major economies" have plans to converge towards or adopt the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS).[11]

History

Accounting is thousands of years old and can be traced to ancient civilizations.[12][13][14] The early development of accounting dates back to ancient Mesopotamia, and is closely related to developments in writing, counting and money;[12] there is also evidence of early forms of bookkeeping in ancient Iran,[15][16] and early auditing systems by the ancient Egyptians and Babylonians.[13] By the time of Emperor Augustus, the Roman government had access to detailed financial information.[17]

Double-entry bookkeeping was pioneered in the Jewish community of the early-medieval Middle East[18][19] and was further refined in medieval Europe.[20] With the development of joint-stock companies, accounting split into financial accounting and management accounting.

The first published work on a double-entry bookkeeping system was the Summa de arithmetica, published in Italy in 1494 by Luca Pacioli (the "Father of Accounting").[21][22] Accounting began to transition into an organized profession in the nineteenth century,[23][24] with local professional bodies in England merging to form the Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales in 1880.[25]

Etymology

Both the words accounting and accountancy were in use in Great Britain by the mid-1800s, and are derived from the words accompting and accountantship used in the 18th century.[26] In Middle English (used roughly between the 12th and the late 15th century) the verb "to account" had the form accounten, which was derived from the Old French word aconter,[27] which is in turn related to the Vulgar Latin word computare, meaning "to reckon". The base of computare is putare, which "variously meant to prune, to purify, to correct an account, hence, to count or calculate, as well as to think".[27]

The word "accountant" is derived from the French word compter, which is also derived from the Italian and Latin word computare. The word was formerly written in English as "accomptant", but in process of time the word, which was always pronounced by dropping the "p", became gradually changed both in pronunciation and in orthography to its present form.[28]

Terminology

Accounting has variously been defined as the keeping or preparation of the financial records of transactions of the firm, the analysis, verification and reporting of such records and "the principles and procedures of accounting"; it also refers to the job of being an accountant.[29][30][31]

Accountancy refers to the occupation or profession of an accountant,[32][33][34] particularly in British English.[29][30]

Topics

Accounting has several subfields or subject areas, including financial accounting, management accounting, auditing, taxation and accounting information systems.[6]

Financial accounting

Financial accounting focuses on the reporting of an organization's financial information to external users of the information, such as investors, potential investors and creditors. It calculates and records business transactions and prepares financial statements for the external users in accordance with generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP).[7] GAAP, in turn, arises from the wide agreement between accounting theory and practice, and change over time to meet the needs of decision-makers.[1]

Financial accounting produces past-oriented reports—for example financial statements are often published six to ten months after the end of the accounting period—on an annual or quarterly basis, generally about the organization as a whole.[7]

Management accounting

Management accounting focuses on the measurement, analysis and reporting of information that can help managers in making decisions to fulfill the goals of an organization. In management accounting, internal measures and reports are based on cost-benefit analysis, and are not required to follow the generally accepted accounting principle (GAAP).[7] In 2014 CIMA created the Global Management Accounting Principles (GMAPs). The result of research from across 20 countries in five continents, the principles aim to guide best practice in the discipline.[35]

Management accounting produces past-oriented reports with time spans that vary widely, but it also encompasses future-oriented reports such as budgets. Management accounting reports often include financial and non financial information, and may, for example, focus on specific products and departments.[7]

Auditing

Auditing is the verification of assertions made by others regarding a payoff,[36] and in the context of accounting it is the "unbiased examination and evaluation of the financial statements of an organization".[37] Audit is a professional service that is systematic and conventional.[38]

An audit of financial statements aims to express or disclaim an independent opinion on the financial statements. The auditor expresses an independent opinion on the fairness with which the financial statements presents the financial position, results of operations, and cash flows of an entity, in accordance with the generally acceptable accounting principle (GAAP) and "in all material respects". An auditor is also required to identify circumstances in which the generally acceptable accounting principles (GAAP) has not been consistently observed.[39]

Information systems

An accounting information system is a part of an organization's information system used for processing accounting data.[40] Many corporations use artificial intelligence-based information systems. The banking and finance industry uses AI in fraud detection. The retail industry uses AI for customer services. AI is also used in the cybersecurity industry. It involves computer hardware and software systems using statistics and modeling.[41]

Many accounting practices have been simplified with the help of accounting computer-based software. An enterprise resource planning (ERP) system is commonly used for a large organisation and it provides a comprehensive, centralized, integrated source of information that companies can use to manage all major business processes, from purchasing to manufacturing to human resources. These systems can be cloud based and available on demand via application or browser, or available as software installed on specific computers or local servers, often referred to as on-premise.

Tax accounting

Tax accounting in the United States concentrates on the preparation, analysis and presentation of tax payments and tax returns. The U.S. tax system requires the use of specialised accounting principles for tax purposes which can differ from the generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) for financial reporting.[42] U.S. tax law covers four basic forms of business ownership: sole proprietorship, partnership, corporation, and limited liability company. Corporate and personal income are taxed at different rates, both varying according to income levels and including varying marginal rates (taxed on each additional dollar of income) and average rates (set as a percentage of overall income).[42]

Forensic accounting

Forensic accounting is a specialty practice area of accounting that describes engagements that result from actual or anticipated disputes or litigation. "Forensic" means "suitable for use in a court of law", and it is to that standard and potential outcome that forensic accountants generally have to work.

Political campaign accounting

Political campaign accounting deals with the development and implementation of financial systems and the accounting of financial transactions in compliance with laws governing political campaign operations. This branch of accounting was first formally introduced in the March 1976 issue of The Journal of Accountancy.[43]

Organizations

Professional bodies

Professional accounting bodies include the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA) and the other 179 members of the International Federation of Accountants (IFAC),[44] including Institute of Chartered Accountants of Scotland (ICAS), Institute of Chartered Accountants of Pakistan (ICAP), CPA Australia, Institute of Chartered Accountants of India, Association of Chartered Certified Accountants (ACCA) and Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales (ICAEW). Professional bodies for subfields of the accounting professions also exist, for example the Chartered Institute of Management Accountants (CIMA) in the UK and Institute of management accountants in the United States.[45] Many of these professional bodies offer education and training including qualification and administration for various accounting designations, such as certified public accountant (AICPA) and chartered accountant.[46][47]

Firms

Depending on its size, a company may be legally required to have their financial statements audited by a qualified auditor, and audits are usually carried out by accounting firms.[10]

Accounting firms grew in the United States and Europe in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, and through several mergers there were large international accounting firms by the mid-twentieth century. Further large mergers in the late twentieth century led to the dominance of the auditing market by the "Big Five" accounting firms: Arthur Andersen, Deloitte, Ernst & Young, KPMG and PricewaterhouseCoopers.[48] The demise of Arthur Andersen following the Enron scandal reduced the Big Five to the Big Four.[49]

Standard-setters

Generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) are accounting standards issued by national regulatory bodies. In addition, the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) issues the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) implemented by 147 countries.[1] While standards for international audit and assurance, ethics, education, and public sector accounting are all set by independent standard settings boards supported by IFAC. The International Auditing and Assurance Standards Board sets international standards for auditing, assurance, and quality control; the International Ethics Standards Board for Accountants (IESBA) [50] sets the internationally appropriate principles- based Code of Ethics for Professional Accounts the International Accounting Education Standards Board (IAESB) sets professional accounting education standards;[51] International Public Sector Accounting Standards Board (IPSASB) sets accrual-based international public sector accounting standards [52]

Organizations in individual countries may issue accounting standards unique to the countries. For example, in the United States the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) issues the Statements of Financial Accounting Standards, which form the basis of US GAAP,[1] and in the United Kingdom the Financial Reporting Council (FRC) sets accounting standards.[53] However, as of 2012 "all major economies" have plans to converge towards or adopt the IFRS.[11]

Education, training and qualifications

Degrees

At least a bachelor's degree in accounting or a related field is required for most accountant and auditor job positions, and some employers prefer applicants with a master's degree.[54] A degree in accounting may also be required for, or may be used to fulfill the requirements for, membership to professional accounting bodies. For example, the education during an accounting degree can be used to fulfill the American Institute of CPA's (AICPA) 150 semester hour requirement,[55] and associate membership with the Certified Public Accountants Association of the UK is available after gaining a degree in finance or accounting.[56]

A doctorate is required in order to pursue a career in accounting academia, for example to work as a university professor in accounting.[57][58] The Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) and the Doctor of Business Administration (DBA) are the most popular degrees. The PhD is the most common degree for those wishing to pursue a career in academia, while DBA programs generally focus on equipping business executives for business or public careers requiring research skills and qualifications.[57]

Professional qualifications

Professional accounting qualifications include the Chartered Accountant designations and other qualifications including certificates and diplomas.[59] In Scotland, chartered accountants of ICAS undergo Continuous Professional Development and abide by the ICAS code of ethics.[60] In England and Wales, chartered accountants of the ICAEW undergo annual training, and are bound by the ICAEW's code of ethics and subject to its disciplinary procedures.[61]

In the United States, the requirements for joining the AICPA as a Certified Public Accountant are set by the Board of Accountancy of each state, and members agree to abide by the AICPA's Code of Professional Conduct and Bylaws.

The ACCA is the largest global accountancy body with over 320,000 members and the organisation provides an ‘IFRS stream’ and a ‘UK stream’. Students must pass a total of 14 exams, which are arranged across three papers.[62]

Research

Accounting research is research in the effects of economic events on the process of accounting, the effects of reported information on economic events, and the roles of accounting in organizations and society.[63][64] It encompasses a broad range of research areas including financial accounting, management accounting, auditing and taxation.[65]

Accounting research is carried out both by academic researchers and practicing accountants. Methodologies in academic accounting research include archival research, which examines "objective data collected from repositories"; experimental research, which examines data "the researcher gathered by administering treatments to subjects"; analytical research, which is "based on the act of formally modeling theories or substantiating ideas in mathematical terms"; interpretive research, which emphasizes the role of language, interpretation and understanding in accounting practice, "highlighting the symbolic structures and taken-for-granted themes which pattern the world in distinct ways"; critical research, which emphasizes the role of power and conflict in accounting practice; case studies; computer simulation; and field research.[66][67]

Empirical studies document that leading accounting journals publish in total fewer research articles than comparable journals in economics and other business disciplines,[68] and consequently, accounting scholars[69] are relatively less successful in academic publishing than their business school peers.[70] Due to different publication rates between accounting and other business disciplines, a recent study based on academic author rankings concludes that the competitive value of a single publication in a top-ranked journal is highest in accounting and lowest in marketing.[71]

Scandals

The year 2001 witnessed a series of financial information frauds involving Enron, auditing firm Arthur Andersen, the telecommunications company WorldCom, Qwest and Sunbeam, among other well-known corporations. These problems highlighted the need to review the effectiveness of accounting standards, auditing regulations and corporate governance principles. In some cases, management manipulated the figures shown in financial reports to indicate a better economic performance. In others, tax and regulatory incentives encouraged over-leveraging of companies and decisions to bear extraordinary and unjustified risk.[72]

The Enron scandal deeply influenced the development of new regulations to improve the reliability of financial reporting, and increased public awareness about the importance of having accounting standards that show the financial reality of companies and the objectivity and independence of auditing firms.[72]

In addition to being the largest bankruptcy reorganization in American history, the Enron scandal undoubtedly is the biggest audit failure[73] causing the dissolution of Arthur Andersen, which at the time was one of the five largest accounting firms in the world. After a series of revelations involving irregular accounting procedures conducted throughout the 1990s, Enron filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection in December 2001.[74]

One consequence of these events was the passage of Sarbanes–Oxley Act in the United States 2002, as a result of the first admissions of fraudulent behavior made by Enron. The act significantly raises criminal penalties for securities fraud, for destroying, altering or fabricating records in federal investigations or any scheme or attempt to defraud shareholders.[75]

Fraud and error

Accounting fraud is an intentional misstatement or omission in the accounting records by management or employees which involves the use of deception. It is a criminal act and a breach of civil tort. It may involve collusion with third parties.[76]

An accounting error is an unintentional misstatement or omission in the accounting records, for example misinterpretation of facts, mistakes in processing data, or oversights leading to incorrect estimates.[76] Acts leading to accounting errors are not criminal but may breach civil law, for example, the tort of negligence.

The primary responsibility for the prevention and detection of fraud and errors rests with the entity's management.[76]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e f Needles, Belverd E.; Powers, Marian (2013). Principles of Financial Accounting. Financial Accounting Series (12 ed.). Cengage Learning.

- ^ Accounting Research Bulletins No. 7 Reports of Committee on Terminology (Report). Committee on Accounting Procedure, American Institute of Accountants. November 1940. Retrieved 31 December 2013.

- ^ Peggy Bishop Lane on Why Accounting Is the Language of Business, Knowledge @ Wharton High School, September 23, 2013, retrieved 25 December 2013

- ^ "Department of Accounting". Foster School of Business. Foster School of Business. 2013. Retrieved 31 December 2013.

- ^ "Accounting Software".

- ^ a b Weber, Richard P., and W. C. Stevenson. 1981. “Evaluations of Accounting Journal and Department Quality.” The Accounting Review 56 (3): 596–612.

- ^ a b c d e f g Horngren, Charles T.; Datar, Srikant M.; Foster, George (2006), Cost Accounting: A Managerial Emphasis (12th ed.), New Jersey: Pearson Prentice Hall

- ^ Lung, Henry (2009). Fundamentals of Financial Accounting. Elsevier.

- ^ DIWAN, Jaswith. ACCOUNTING CONCEPTS & THEORIES. LONDON: MORRE. pp. 001–002. id# 94452.

- ^ a b "Auditors: Market concentration and their role, CHAPTER 1: Introduction". UK Parliament. House of Lords. 2011. Retrieved 1 January 2014.

- ^ a b IFRS Foundation, 2012. The move towards global standards Archived 2011-12-25 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on April 27, 2012.

- ^ a b Robson, Keith. 1992. “Accounting Numbers as ‘inscription’: Action at a Distance and the Development of Accounting.” Accounting, Organizations and Society 17 (7): 685–708.

- ^ a b A History of ACCOUNTANCY, New York State Society of CPAs, November 2003, retrieved 28 December 2013

- ^ The History of Accounting, University of South Australia, April 30, 2013, archived from the original on 28 December 2013, retrieved 28 December 2013

- ^ کشاورزی, کیخسرو (1980). تاریخ ایران از زمان باستان تا امروز (Translated from Russian by Grantovsky, E.A.) (in Persian). pp. 39–40.

- ^ Oldroyd, David & Dobie, Alisdair: Themes in the history of bookkeeping, The Routledge Companion to Accounting History, London, July 2008, ISBN 978-0-415-41094-6, Chapter 5, p. 96

- ^ Oldroyd, David: The role of accounting in public expenditure and monetary policy in the first century AD Roman Empire, Accounting Historians Journal, Volume 22, Number 2, Birmingham, Alabama, December 1995, p.124, Olemiss.edu

- ^ Parker, L. M., “Medieval Traders as International Change Agents: A Comparison with Twentieth Century International Accounting Firms,” The Accounting Historians Journal, 16(2) (1989): 107-118.

- ^ MEDIEVAL TRADERS AS INTERNATIONAL CHANGE AGENTS: A COMMENT, Michael Scorgie, The Accounting Historians Journal, Vol. 21, No. 1 (June 1994), pp. 137-143

- ^ Heeffer, Albrecht (November 2009). "On the curious historical coincidence of algebra and double-entry bookkeeping" (PDF). Foundations of the Formal Sciences. Ghent University. p. 11.

- ^ Mariotti, Steve (2013-07-12). "So, Who Invented Double Entry Bookkeeping? Luca Pacioli or Benedikt Kotruljević?". Huffington Post. Retrieved 2018-08-03.

- ^ Lauwers, Luc & Willekens, Marleen: "Five Hundred Years of Bookkeeping: A Portrait of Luca Pacioli" (Tijdschrift voor Economie en Management, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, 1994, vol:XXXIX issue 3, p.302), KUleuven.be

- ^ Timeline of the History of the Accountancy Profession, Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales, 2013, retrieved 28 December 2013

- ^ Stephen A. Zeff (2003), "How the U.S. Accounting Profession Got Where It Is Today: Part I" (PDF), Accounting Horizons, 17 (3): 189–205, doi:10.2308/acch.2003.17.3.189, retrieved 16 May 2020

- ^ Perks, R. W. (1993). Accounting and Society. London: Chapman & Hall. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-412-47330-2.

- ^ Labardin, Pierre, and Marc Nikitin. 2009. “Accounting and the Words to Tell It: An Historical Perspective.” Accounting, Business & Financial History 19 (2): 149–166.

- ^ a b Baladouni, Vahé. 1984. “Etymological Observations on Some Accounting Terms.” The Accounting Historians Journal 11 (2): 101–109.

- ^ Pixley, Francis William: Accountancy—constructive and recording accountancy (Sir Isaac Pitman & Sons, Ltd, London, 1900), p4

- ^ a b "accounting noun - definition in the Business English Dictionary". Cambridge Dictionaries Online. Cambridge University Press. 2013. Retrieved 30 December 2013.

- ^ a b "accounting noun - definition in the British English Dictionary & Thesaurus". Cambridge Dictionaries Online. Cambridge University Press. 2013. Retrieved 30 December 2013.

- ^ "accounting". Merriam-Webster. Merriam-Webster, Incorporated. 2013. Retrieved 30 December 2013.

- ^ "accountancy". Merriam-Webster. Merriam-Webster, Incorporated. 2013. Retrieved 30 December 2013.

- ^ "accountancy noun - definition in the Business English Dictionary". Cambridge Dictionaries Online. Cambridge University Press. 2013. Retrieved 30 December 2013.

- ^ "accountancy noun - definition in the British English Dictionary & Thesaurus". Cambridge Dictionaries Online. Cambridge University Press. 2013. Retrieved 30 December 2013.

- ^ King, I. "New set of accounting principles can help drive sustainable success". ft.com. Retrieved 28 January 2015.

- ^ Baiman, Stanley. 1979. “Discussion of Auditing: Incentives and Truthful Reporting.” Journal of Accounting Research 17: 25–29.

- ^ "Audit Definition". Investopedia. Investopedia US. 2013. Retrieved 30 December 2013.

- ^ Tredinnick, Luke (March 2017). "Artificial intelligence and professional roles" (PDF). Business Information Review. 34 (1): 37–41. doi:10.1177/0266382117692621. S2CID 157743821.

- ^ "Responsibilities and Functions of the Independent Auditor" (PDF). AICPA. AICPA. November 1972. Retrieved 30 December 2013.

- ^ "1.2 Accounting information systems". Introduction to the context of accounting. OpenLearn. Retrieved 3 February 2014.

- ^ Pathak, Jagdish; Lind, Mary R. (November 2003). "Audit Risk, Complex Technology, and Auditing Processes". EDPACS. 31 (5): 1–9. doi:10.1201/1079/43853.31.5.20031101/78844.1. S2CID 61767095.

- ^ a b Droms, William G.; Wright, Jay O. (2010), Finance and Accounting for nonfinancial Managers: All the Basics you need to Know (6th ed.), Basic Books, 2010

- ^ "Political campaign accounting--New opportunities for the CPA - ProQuest" (PDF). search.proquest.com. pp. 36–41. Retrieved 2020-09-09.

- ^ "IFAC Members". ifac.org. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- ^ "Accounting Bodies Network". The Prince's Accounting for Sustainability Project. Archived from the original on 3 January 2014. Retrieved 3 January 2014.

- ^ "Getting Started". AICPA. AICPA. 2014. Retrieved 3 January 2014.

- ^ "The ACA Qualification". ICAEW. ICAEW. 2014. Retrieved 3 January 2014.

- ^ "Auditors: Market concentration and their role, CHAPTER 2: Concentration in the audit market". UK Parliament. House of Lords. 2011. Retrieved 1 January 2014.

- ^ "Definition of big four". Financial Times Lexicon. The Financial Times Ltd. 2014. Retrieved 1 January 2014.

- ^ "IESBA | Ethics | Accounting | IFAC". ifac.org. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- ^ "IAESB | International Accounting Education Standards Board | IFAC". ifac.org. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- ^ "IPSASB | International Public Sector Accounting Standards Board | IFAC". ifac.org. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- ^ Knowledge guide to UK Accounting Standards, ICAEW, 2014, retrieved 1 January 2014

- ^ "How to Become an Accountant or Auditor". U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. United States Department of Labor. 2012. Retrieved 31 December 2013.

- ^ "150 Hour Requirement for Obtaining CPA Certification". AICPA. AICPA. 2013. Retrieved 31 December 2013.

- ^ "Criteria for entry". CPA UK. CPA UK. 2013. Archived from the original on 19 August 2013. Retrieved 31 December 2013.

- ^ a b "Want a Career in Education? Here's What You Need to Know". AICPA. AICPA. 2013. Archived from the original on 1 January 2014. Retrieved 31 December 2013.

- ^ "PhD Prep Track". BYU Accounting. BYU Accounting. 2013. Retrieved 31 December 2013.

- ^ "Accountancy Qualifications at a Glance". ACCA. 2014. Retrieved 4 January 2014.

- ^ Kyle, McHatton. "ICAS code of ethics". www.icas.com. Retrieved 2018-10-18.

- ^ "ACA – The qualification of ICAEW Chartered Accountants". ICAEW. 2014. Archived from the original on 11 October 2013. Retrieved 4 January 2014.

- ^ "European Accounting Qualifications Explained | CareersinAudit.com". CareersinAudit.com. Retrieved 2017-12-13.

- ^ The Relevance and Utility of Leading Accounting Research (PDF), The Association of Chartered Certified Accountants, 2010, archived from the original (PDF) on December 27, 2013, retrieved December 27, 2013

- ^ Burchell, S.; Clubb, C.; Hopwood, A.; Hughes, J.; Nahapiet, J. (1980). "The roles of accounting in organizations and society". Accounting, Organizations and Society. 5 (1): 5–27. doi:10.1016/0361-3682(80)90017-3.

- ^ Oler, Derek K., Mitchell J. Oler, and Christopher J. Skousen. 2010. “Characterizing Accounting Research.” Accounting Horizons 24 (4): 635–670.

- ^ Coyne, Joshua G., Scott L. Summers, Brady Williams, and David a. Wood. 2010. “Accounting Program Research Rankings by Topical Area and Methodology.” Issues in Accounting Education 25 (4) (November): 631–654.

- ^ Chua, Wai Fong (1986). "Radical developments in accounting thought". The Accounting Review. 61 (4): 601–632.

- ^ Buchheit, S.; Collins, D.; Reitenga, A. (2002). "A cross-discipline comparison of top-tier academic journal publication rates: 1997–1999". Journal of Accounting Education. 20 (2): 123–130. doi:10.1016/S0748-5751(02)00003-9.

- ^ Merigo, Jose M.; Yang, Jian-Bo (2017). "Accounting Research: A Bibliometric Analysis". Australian Accounting Review. 27: 71–100. doi:10.1111/auar.12109. ISSN 1835-2561.

- ^ Swanson, Edward (2004). "Publishing in the majors: A comparison of accounting, finance, management, and marketing". Contemporary Accounting Research. 21: 223–255. doi:10.1506/RCKM-13FM-GK0E-3W50.

- ^ Korkeamäki, Timo; Sihvonen, Jukka; Vähämaa, Sami (2018). "Evaluating publications across business disciplines". Journal of Business Research. 84: 220–232. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2017.11.024.

- ^ a b Astrid Ayala and Giancarlo Ibárgüen Snr.: "A Market Proposal for Auditing the Financial Statements of Public Companies" (Journal of Management of Value, Universidad Francisco Marroquín, March 2006) p. 41, UFM.edu.gt

- ^ Bratton, William W. "Enron and the Dark Side of Shareholder Value" (Tulane Law Review, New Orleans, May 2002) p. 61

- ^ "Enron files for bankruptcy". BBC News. 2001-12-03. Retrieved 15 March 2008.

- ^ Aiyesha Dey, and Thomas Z. Lys: "Trends in Earnings Management and Informativeness of Earnings Announcements in the Pre- and Post-Sarbanes Oxley Periods (Kellogg School of Management, Evanston, Illinois, February, 2005) p. 5

- ^ a b c 2018 Handbook of International Quality Control, Auditing, Review, Other Assurance, and Related Services Pronouncements, The International Auditing and Assurance Standards Board, December 2018

External links

- Library resources in your library and in other libraries about accounting

- Operations Research in Accounting on the Institute for Operations Research and the Management Sciences website