André Breton

André Breton | |

|---|---|

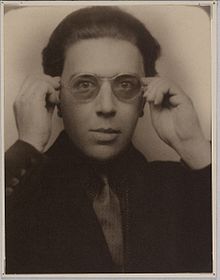

Breton in 1924 | |

| Born | André Robert Breton 18 February 1896 Tinchebray, Orne, France |

| Died | 28 September 1966 (aged 70) Paris, France |

| Occupation | Writer |

| Period | 20th century |

| Genre | Histories, poetry, essays |

| Literary movement | Surrealism |

| Notable works | Surrealist Manifesto |

| Spouse |

Simone Kahn

(m. 1921; div. 1931) |

| Children | Aube Breton |

| Part of a series on |

| Surrealism |

|---|

| Aspects |

| Groups |

André Robert Breton (French: [ɑ̃dʁe ʁɔbɛʁ bʁətɔ̃]; 18 February 1896 – 28 September 1966) was a French writer and poet. He is known best as the co-founder, leader, principal theorist and chief apologist of surrealism.[1] His writings include the first Surrealist Manifesto (Manifeste du surréalisme) of 1924, in which he defined surrealism as "pure psychic automatism".[2]

Along with his role as leader of the surrealist movement he is the author of celebrated books such as Nadja and L'Amour fou. Those activities combined with his critical and theoretical work for writing and the plastic arts, made André Breton a major figure in twentieth-century French art and literature.

Biography

André Breton was the only son born to a family of modest means in Tinchebray (Orne) in Normandy, France. His father, Louis-Justin Breton, was a policeman and atheistic, and his mother, Marguerite-Marie-Eugénie Le Gouguès, was a former seamstress. Breton attended medical school, where he developed a particular interest in mental illness.[3] His education was interrupted when he was conscripted for World War I.[3]

During World War I, he worked in a neurological ward in Nantes, where he met the devotee of Alfred Jarry, Jacques Vaché, whose anti-social attitude and disdain for established artistic tradition influenced Breton considerably.[4] Vaché committed suicide when aged 24, and his war-time letters to Breton and others were published in a volume entitled Lettres de guerre (1919), for which Breton wrote four introductory essays.[5]

Breton married his first wife, Simone Kahn, on 15 September 1921. The couple relocated to rue Fontaine No. 42 in Paris on 1 January 1922. The apartment on rue Fontaine (in the Pigalle district) became home to Breton's collection of more than 5,300 items: modern paintings, drawings, sculptures, photographs, books, art catalogs, journals, manuscripts, and works of popular and Oceanic art. Like his father, he was an atheist.[6][7][8][9]

From Dada to Surrealism

Breton launched the review Littérature in 1919, with Louis Aragon and Philippe Soupault.[10] He also associated with Dadaist Tristan Tzara.[11] In 1924, he was instrumental in the founding of the Bureau of Surrealist Research.[12]

In Les Champs Magnétiques[13] (The Magnetic Fields), a collaboration with Soupault, he implemented the principle of automatic writing. He published the Surrealist Manifesto in 1924, and was editor of the magazine La Révolution surréaliste from that year on. A group of writers became associated with him: Soupault, Louis Aragon, Paul Éluard, René Crevel, Michel Leiris, Benjamin Péret, Antonin Artaud, and Robert Desnos.

Anxious to combine the themes of personal transformation found in the works of Arthur Rimbaud with the politics of Karl Marx, Breton joined the French Communist Party in 1927, from which he was expelled in 1933. Nadja, a novel about his encounter with an imaginative woman who later became mentally ill, was published in 1928. Breton celebrated the concept of Mad Love, and many women joined the surrealist group over the years. Toyen was a good friend. During this time, he survived mostly by the sale of paintings from his art gallery.[14][15]

In 1930, Un Cadavre, a pamphlet, was written and released by several members of the surrealist movement who were insulted by Breton or had otherwise disbelieved in his leadership.[16]: 299–302 The pamphlet criticized Breton's oversight and influence over the movement. It marked a divide amidst the early surrealists.

In 1935, there was a conflict between Breton and the Soviet writer and journalist Ilya Ehrenburg during the first International Congress of Writers for the Defense of Culture, which opened in Paris in June. Breton had been insulted by Ehrenburg—along with all fellow surrealists—in a pamphlet which said, among other things, that surrealists were "pederasts". Breton slapped Ehrenburg several times on the street, which resulted in surrealists being expelled from the Congress. René Crevel, who according to Salvador Dalí was "the only serious communist among surrealists",[17] was isolated from Breton and other surrealists, who were unhappy with Crevel because of his bisexuality and annoyed with communists in general.[14]

In 1938, Breton accepted a cultural commission from the French government to travel to Mexico. After a conference at the National Autonomous University of Mexico about surrealism, Breton stated after getting lost in Mexico City (as no one was waiting for him at the airport) "I don't know why I came here. Mexico is the most surrealist country in the world".

However, visiting Mexico provided the opportunity to meet Leon Trotsky. Breton and other surrealists traveled via a long boat ride from Patzcuaro to the town of Erongarícuaro. Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo were among the visitors to the hidden community of intellectuals and artists. Together, Breton and Trotsky wrote the Manifesto for an Independent Revolutionary Art (published under the names of Breton and Diego Rivera) calling for "complete freedom of art", which was becoming increasingly difficult with the world situation of the time.

World War II and exile

Breton was again in the medical corps of the French Army at the start of World War II. The Vichy government banned his writings as "the very negation of the national revolution"[18] and Breton escaped, with the help of the American Varian Fry and Hiram "Harry" Bingham IV, to the United States and the Caribbean during 1941.[19][20] He emigrated to New York City and lived there for a few years.[3] In 1942, Breton organized a groundbreaking surrealist exhibition at Yale University.[3]

In 1942,[21] Breton collaborated with artist Wifredo Lam on the publication of Breton's poem "Fata Morgana", which was illustrated by Lam.

Breton got to know Martinican writer Aimé Césaire, and later composed the introduction to the 1947 edition of Césaire's Cahier d'un retour au pays natal. During his exile in New York City he met Elisa Bindhoff, the Chilean woman who would become his third wife.[14]

In 1944, he and Elisa traveled to the Gaspé Peninsula in Québec, where he wrote Arcane 17, a book which expresses his fears of World War II, describes the marvels of the Percé Rock and the extreme northeastern part of North America, and celebrates his new romance with Elisa.[14]

During his visit to Haiti in 1945–46, he sought to connect surrealist politics and automatist practices with the legacies of the Haitian Revolution and the ritual practices of Vodou possession. Recent developments in Haitian painting were central to his efforts, as can be seen from a comment that Breton left in the visitors' book at the Centre d'Art in Port-au-Prince: "Haitian painting will drink the blood of the phoenix. And, with the epaulets of [Jean-Jacques] Dessalines, it will ventilate the world." Breton was specifically referring to the work of painter and Vodou priest Hector Hyppolite, whom he identified as the first artist to directly depict Vodou scenes and the lwa (Vodou deities), as opposed to hiding them in chromolithographs of Catholic saints or invoking them through impermanent vevé (abstracted forms drawn with powder during rituals). Breton's writings on Hyppolite were undeniably central to the artist's international status from the late 1940s on, but the surrealist readily admitted that his understanding of Hyppolite's art was inhibited by their lack of a common language. Returning to France with multiple paintings by Hyppolite, Breton integrated this artwork into the increased surrealist focus on the occult, myth, and magic.[22]

Later life

Breton returned to Paris in 1946, where he opposed French colonialism (for example as a signatory of the Manifesto of the 121 against the Algerian War) and continued, until his death, to foster a second group of surrealists in the form of expositions or reviews (La Brèche, 1961–65). In 1959, he organized an exhibit in Paris.[14]

By the end of World War II, André Breton decided to embrace anarchism explicitly. In 1952, Breton wrote "It was in the black mirror of anarchism that surrealism first recognised itself."[23] Breton consistently supported the francophone Anarchist Federation and he continued to offer his solidarity after the Platformists around founder and Secretary General Georges Fontenis transformed the FA into the Fédération communiste libertaire.[14][23]

Like a small number of intellectuals during the time of the Algerian War, he continued to support the FCL when it was forced to go underground, even providing shelter to Fontenis, who was in hiding. He refused to take sides in the politically divided French anarchist movement, even though both he and Péret) expressed solidarity to the new Anarchist Federation rebuilt by a group of synthesist anarchists. He also worked with the FA in the Anti-Fascist Committees in the 1960s.[23]

Death

André Breton died at the age of 70 in 1966, and was buried in the Cimetière des Batignolles in Paris.[24]

Legacy

Breton as a collector

Breton was an avid collector of art, ethnographic material, and unusual trinkets. He was particularly interested in materials from the northwest coast of North America. During a financial crisis he experienced in 1931, most of his collection (along with that of his friend Paul Éluard) was auctioned. He subsequently rebuilt the collection in his studio and home at 42 rue Fontaine. The collection grew to over 5,300 items: modern paintings, drawings, sculptures, photographs, books, art catalogs, journals, manuscripts, and works of popular and Oceanic art.[25]

French anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss, in an interview in 1971, spoke about Breton's skill in determining the authenticity of objects. Strauss even described their friendship while the two were living in New York: "We lived in New York between 1941 and 1945 in a great friendship, running museums and antiquarians together. I owe him a lot about the knowledge and appreciation of objects. I've never seen him [Breton] doing a mistake on exotic and unusual objects. When I say a mistake, I mean about its authenticity but also its quality. He [Breton] had a sense, almost of divination."[15][citation needed]

After Breton's death on 28 September 1966, his third wife, Elisa, and his daughter, Aube, allowed students and researchers access to his archive and collection. After thirty-six years, when attempts to establish a surrealist foundation to protect the collection were opposed, the collection was auctioned by Calmels Cohen at Drouot-Richelieu. A wall of the apartment is preserved at the Centre Georges Pompidou.[26]

Nine previously unpublished manuscripts, including the Manifeste du surréalisme, were auctioned by Sotheby's in May 2008.[27]

Marriages

Breton married three times:[14]

- from 1921 to 1931, to Simone Collinet, née Kahn (1897–1980);

- from 1934 to 1943, to Jacqueline Lamba, with whom he had his only child, a daughter, Aube Elléouët Breton;

- from 1945 to 1966 (his death), to Elisa Bindhoff Enet.

Works

- 1919: Mont de Piété – [Literally: Pawn Shop]

- 1920: S'il Vous Plaît – Published in English as: If You Please

- 1920: Les Champs magnétiques (with Philippe Soupault) – Published in English as: The Magnetic Fields

- 1923: Clair de terre – Published in English as: Earthlight

- 1924: Les Pas perdus – Published in English as: The Lost Steps

- 1924: Manifeste du surréalisme – Published in English as: Surrealist Manifesto

- 1924: Poisson soluble – [Literally: Soluble Fish]

- 1924: Un Cadavre – [Literally: A Corpse]

- 1926: Légitime défense – [Literally: Legitimate Defense]

- 1928: Le Surréalisme et la peinture – Published in English as: Surrealism and Painting

- 1928: Nadja – Published in English as: Nadja

- 1930: Ralentir travaux (with René Char and Paul Éluard) – [Literally: Slow Down, Men at Work]

- 1930: Deuxième Manifeste du surréalisme – Published in English as: The Second Manifesto of Surrealism

- 1930: L'Immaculée Conception (with Paul Éluard) – Published in English as: Immaculate Conception

- 1931: L'Union libre – [Literally: Free Union]

- 1932: Misère de la poésie – [Literally: Poetry's Misery]

- 1932: Le Revolver à cheveux blancs – [Literally: The White-Haired Revolver]

- 1932: Les Vases communicants – Published in English as: Communicating Vessels

- 1933: Le Message automatique – Published in English as: The Automatic Message

- 1934: Qu'est-ce que le Surréalisme? – Published in English as: What Is Surrealism?

- 1934: Point du Jour – Published in English as: Break of Day

- 1934: L'Air de l'eau – [Literally: The Air of the Water]

- 1935: Position politique du surréalisme – [Literally: Political Position of Surrealism]

- 1936: Au Lavoir noir – [Literally: At the black Washtub]

- 1936: Notes sur la poésie (with Paul Éluard) – [Literally: Notes on Poetry]

- 1937: Le Château étoilé – [Literally: The Starry Castle]

- 1937: L'Amour fou – Published in English as: Mad Love

- 1938: Trajectoire du rêve – [Literally: Trajectory of Dream]

- 1938: Dictionnaire abrégé du surréalisme (with Paul Éluard) – [Literally: Abridged Dictionary of Surrealism]

- 1938: Pour un art révolutionnaire indépendant (with Diego Rivera) – [Literally: For an Independent Revolutionary Art]

- 1940: Anthologie de l'humour noir – Published in English as: Anthology of Black Humor

- 1941: "Fata Morgana" – [A long poem included in subsequent anthologies]

- 1943: Pleine Marge – [Literally: Full Margin]

- 1944: Arcane 17 – Published in English as: Arcanum 17

- 1945: Le Surréalisme et la peinture – Published in English as: Surrealism and Painting

- 1945: Situation du surréalisme entre les deux guerres – [Literally: Situation of Surrealism between the two wars]

- 1946: Yves Tanguy

- 1946: Les Manifestes du surréalisme – Published in English as: Manifestoes of Surrealism

- 1946: Young Cherry Trees Secured against Hares – Jeunes cerisiers garantis contre les lièvres [Bilingual edition of poems translated by Edouard Roditi]

- 1947: Ode à Charles Fourier – Published in English as: Ode To Charles Fourier

- 1948: Martinique, charmeuse de serpents – Published in English as: Martinique: Snake Charmer

- 1948: La Lampe dans l'horloge – [Literally: The Lamp in the Clock]

- 1948: Poèmes 1919–48 – [Literally: Poems 1919–48]

- 1949: Flagrant délit – [Literally: Red-handed]

- 1952 Entretiens – – Published in English as: Conversations: The Autobiography of Surrealism

- 1953: La Clé des Champs – Published in English as: Free Rein

- 1954: Farouche à quatre feuilles (with Lise Deharme, Julien Gracq, Jean Tardieu) – [Literally: Four-Leaf Feral]

- 1955: Les Vases communicants [Expanded edition] – Published in English as: Communicating Vessels

- 1955: Les Manifestes du surréalisme [Expanded edition] – Published in English as: Manifestoes of Surrealism

- 1957: L'Art magique – Published in English as: Magical Art

- 1959: Constellations (with Joan Miró) – Published in English as: Constellations

- 1961: Le la – [Literally: The A]

- 1962: Les Manifestes du surréalisme [Expanded edition] – Published in English as: Manifestoes of Surrealism

- 1963: Nadja [Expanded edition] – Published in English as: Nadja

- 1965: Le Surréalisme et la peinture [Expanded edition] – Published in English as: Surrealism and Painting

- 1966: Anthologie de l'humour noir [Expanded edition] – Published in English as: Anthology of Black Humor

- 1966: Clair de terre – (Anthology of poems 1919-1936). Published in English as: Earthlight

- 1968: Signe ascendant – (Anthology of poems 1935-1961). [Literally: Ascendant Sign]

- 1970: Perspective cavalière – [Literally: Cavalier Perspective]

- 1988: Breton : Oeuvres complètes, tome 1 – [Literally: Breton: The Complete Works, tome 1]

- 1992: Breton : Oeuvres complètes, tome 2 – [Literally: Breton: The Complete Works, tome 2]

- 1999: Breton : Oeuvres complètes, tome 3 – [Literally: Breton: The Complete Works, tome 3]

See also

References

- ^ Lawrence Gowing, ed., Biographical Encyclopedia of Artists, v.1 (Facts on File, 2005): 84.

- ^ André Breton (1969). Manifestoes of Surrealism. University of Michigan Press. p. 26. ISBN 0472061828.

- ^ a b c d "André Breton". Biography.com. Archived from the original on 2017-05-06. Retrieved 2020-07-11.

- ^ Henri Béhar, Catherine Dufour (2005). Dada, circuit total. L'AGE D'HOMME. p. 552. ISBN 9782825119068.

- ^ Vaché, Jacques (1949). Lettres de guerre. André Breton (2ème publication ed.).

- ^ Reviewing Mark Polizzotti's Revolution of the Mind: The Life of André Breton Douglas F. Smith called him, "[a] cynical atheist, the poet, critic, and artist harbored an irrepressible streak of romanticism."

- ^ "To speak of God, to think of God, is in every respect to show what one is made of.... I have always wagered against God and I regard the little that I have won in this world as simply the outcome of this bet. However paltry may have been the stake (my life) I am conscious of having won to the full. Everything that is doddering, squint-eyed, vile, polluted and grotesque is summoned up for me in that one word: God!" - André Breton, taking from a footnote from his book, Surrealism and Painting. Quotations by the poet: Andre Breton

- ^ Gilson, Étienne (1988). Linguistics and philosophy: an essay on the philosophical constants of language. University of Notre Dame Press. p. 98. ISBN 978-0-268-01284-7.

Breton professed to be an atheist...

- ^ Browder, Clifford (1967). André Breton: Arbiter of Surrealism. Droz. p. 133.

Again, the atheist Breton's predilection for ideas of blasphemy and profanation, as well as for the " demonic " word noir, contained a hint of Satanism and alliance with infernal powers.

- ^ "Lost Profiles, Memoirs of Cubism, Dada, and Surrealism". www.citylights.com. Retrieved 2019-06-11.

- ^ "Tristan Tzara Art, Bio, Ideas". The Art Story. Retrieved 2019-06-11.

- ^ ramalhodiogo (2012-07-24). "Bureau of Surrealist Research". Frequently Asked Questions. Retrieved 2019-06-11.

- ^ "Les Champs magnétiques (André Breton)". www.andrebreton.fr (in French). Retrieved 2019-06-11.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c d e f g Polizzotti, Mark. (2009). Revolution of the mind : the life of André Breton (1st Black Widow Press ed., rev. & updated ed.). Boston, Mass.: Black Widow Press. ISBN 9780979513787. OCLC 221148942.

- ^ a b Douglas, Ava. "André Breton". www.historygraphicdesign.com. Archived from the original on 2019-02-12. Retrieved 2019-02-25.

- ^ Polizzotti, Mark (2009) [First published 1995]. Revolution of the Mind (Revised and updated ed.). Boston, MA: First Black Widow Press. ISBN 978-0-9795137-8-7.

- ^ Crevel, René. Le Clavecin de Diderot, Afterword. p. 161.

- ^ Franklin Rosemont André Breton and the First Principles of Surrealism, 1978, ISBN 0-904383-89-X.

- ^ Schiffrin, Anya (2019-10-03). "How Varian Fry Helped My Family Escape the Nazis". NYR Daily. Retrieved 2020-07-11.

- ^ "Emergency Escape: Vatican Fry". Americans and the Holocaust. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved 2020-07-11.

- ^ André Breton, Fata Morgana. Buenos Aires: Éditions des lettres françaises, Sur, 1942.

- ^ Geis, T. (2015). "Myth, History and Repetition: André Breton and Vodou in Haiti". South Central Review. 32 (1): 56–75. doi:10.1353/scr.2015.0010. S2CID 143481322.

- ^ a b c "1919–1950: The politics of Surrealism by Nick Heath". Libcom.org. Retrieved 26 December 2009.

- ^ Art, Surrealism. "André Breton | Father of Surrealism". www.surrealismart.org. Retrieved 2018-01-24.

- ^ André Breton, 42, rue Fontaine: tableaux modernes, sculptures, estampes, tableaux anciens. Paris: CalmelsCohen, 2003.

- ^ "Surrealist Art", Centre Pompidou - Art Culture Mus. 11 March 2010. centrepompidou.fr Archived 9 February 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Nine Manuscripts by André Breton at Sotheby's Paris". ArtDaily.org. 20 May 2008. Retrieved 28 March 2009.

Further reading

- André Breton: Surrealism and Painting – edited and with an introduction by Mark Polizzotti.

- Manifestoes of Surrealism by André Breton, translated by Richard Seaver and Helen R. Lane. ISBN 0-472-06182-8

External links

Media related to André Breton at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to André Breton at Wikimedia Commons Quotations related to André Breton at Wikiquote

Quotations related to André Breton at Wikiquote French Wikisource has original text related to this article: André Breton

French Wikisource has original text related to this article: André Breton- André Breton's Nadja (in French)

- André Breton in American public collections, on the French Sculpture Census website

- 1896 births

- 1966 deaths

- Modernist writers

- French anarchists

- French atheists

- French Communist Party members

- French surrealist writers

- Surrealist poets

- French Trotskyists

- Dada

- Libertarian socialists

- Marxist writers

- People from Orne

- Writers from Normandy

- Burials at Batignolles Cemetery

- 20th-century French poets

- 20th-century French novelists

- 20th-century male writers