Bad breath

| Bad breath | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Halitosis, fetor oris, oral malodour, putrid breath |

| |

| Specialty | Gastroenterology, otorhinolaryngology, dentistry |

| Symptoms | Unpleasant smell present on breath[1] |

| Complications | Anxiety, depression, obsessive compulsive disorder[1] |

| Types | Genuine, non-genuine[2] |

| Causes | Usually from inside the mouth[1] |

| Treatment | Depends on cause, tongue cleaning, mouthwash, flossing[1] |

| Medication | Mouthwash containing chlorhexidine or cetylpyridinium chloride[1][3] |

| Frequency | ~30% of people[1] |

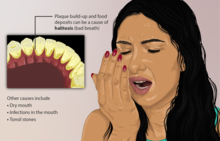

Bad breath, also known as halitosis, is a symptom in which a noticeably unpleasant breath odour is present.[1] It can result in anxiety among those affected.[1] It is also associated with depression and symptoms of obsessive compulsive disorder.[1]

The concerns of bad breath may be divided into genuine and non-genuine cases.[2] Of those who have genuine bad breath, about 85% of cases come from inside the mouth.[1] The remaining cases are believed to be due to disorders in the nose, sinuses, throat, lungs, esophagus, or stomach.[4] Rarely, bad breath can be due to an underlying medical condition such as liver failure or ketoacidosis.[2] Non-genuine cases occur when someone complains of having bad breath but other people cannot detect it.[2] This is estimated to make up between 5% and 72% of cases.[2]

The treatment depends on the underlying cause.[1] Initial efforts may include tongue cleaning, mouthwash, and flossing.[1] Tentative evidence supports the use of mouthwash containing chlorhexidine or cetylpyridinium chloride.[1][3] While there is tentative evidence of benefit from the use of a tongue cleaner it is insufficient to draw clear conclusions.[5] Treating underlying disease such as gum disease, tooth decay, tonsil stones, or gastroesophageal reflux disease may help.[1] Counselling may be useful in those who falsely believe that they have bad breath.[1]

Estimated rates of bad breath vary from 6% to 50% of the population.[1] Concern about bad breath is the third most common reason people seek dental care, after tooth decay and gum disease.[2][4] It is believed to become more common as people age.[1] Bad breath is viewed as a social taboo and those affected may be stigmatized.[1][2] People in the United States spend more than $1 billion per year on mouthwash to treat it.[4]

Signs and symptoms

Bad breath is when a noticeably unpleasant odour is believed to be present on the breath. It can result in anxiety among those affected. It is also associated with depression and symptoms of obsessive compulsive disorder.[1]

Causes

Mouth

In about 90% of genuine halitosis cases, the origin of the odour is in the mouth itself.[6] This is known as intra-oral halitosis, oral malodour or oral halitosis.

The most common causes are odour producing biofilm on the back of the tongue or other areas of the mouth due to poor oral hygiene. This biofilm results in the production of high levels of foul odours. The odours are produced mainly due to the breakdown of proteins into individual amino acids, followed by the further breakdown of certain amino acids to produce detectable foul gases. Volatile sulfur compounds are associated with oral malodour levels, and usually decrease following successful treatment.[7] Other parts of the mouth may also contribute to the overall odour, but are not as common as the back of the tongue. These locations are, in order of descending prevalence, inter-dental and sub-gingival niches, faulty dental work, food-impaction areas in between the teeth, abscesses, and unclean dentures.[8] Oral based lesions caused by viral infections like herpes simplex and HPV may also contribute to bad breath.

The intensity of bad breath may differ during the day, due to eating certain foods (such as garlic, onions, meat, fish, and cheese), smoking,[9] and alcohol consumption. Since the mouth is exposed to less oxygen[medical citation needed] and is inactive during the night, the odour is usually worse upon awakening ("morning breath"). Bad breath may be transient, often disappearing following eating, drinking, tooth brushing, flossing, or rinsing with specialized mouthwash. Bad breath may also be persistent (chronic bad breath), which affects some 25% of the population in varying degrees.[10]

Tongue

The most common location for mouth-related halitosis is the tongue.[11] Tongue bacteria produce malodourous compounds and fatty acids, and account for 80 to 90% of all cases of mouth-related bad breath.[12] Large quantities of naturally occurring bacteria are often found on the posterior dorsum of the tongue, where they are relatively undisturbed by normal activity. This part of the tongue is relatively dry and poorly cleansed, and the convoluted microbial structure of the tongue dorsum provides an ideal habitat for anaerobic bacteria, which flourish under a continually-forming tongue coating of food debris, dead epithelial cells, postnasal drip and overlying bacteria, living and dead. When left on the tongue, the anaerobic respiration of such bacteria can yield either the putrescent smell of indole, skatole, polyamines, or the "rotten egg" smell of volatile sulfur compounds (VSCs) such as hydrogen sulfide, methyl mercaptan, allyl methyl sulfide, and dimethyl sulfide. The presence of halitosis-producing bacteria on the back of the tongue is not to be confused with tongue coating. Bacteria are invisible to the naked eye, and degrees of white tongue coating are present in most people with and without halitosis. A visible white tongue coating does not always equal the back of the tongue as an origin of halitosis, however a "white tongue" is thought to be a sign of halitosis. In oral medicine generally, a white tongue is considered a sign of several medical conditions. Patients with periodontal disease were shown to have sixfold prevalence of tongue coating compared with normal subjects. Halitosis patients were also shown to have significantly higher bacterial loads in this region compared to individuals without halitosis.

Gums

Gingival crevices are the small grooves between teeth and gums, and they are present in health, although they may become inflamed when gingivitis is present. The difference between a gingival crevice and periodontal pocket is that former is <3mm in depth and the latter is >3mm. Periodontal pockets usually accompany periodontal disease (gum disease). There is some controversy over the role of periodontal diseases in causing bad breath. However, advanced periodontal disease is a common cause of severe halitosis. People with uncontrolled diabetes are more prone to have multiple gingival and periodontal abscess. Their gums are evident with large pockets, where pus accumulation occurs. This nidus of infection can be a potential source for bad breath. Removal of the subgingival calculus (i.e. tartar or hard plaque) and friable tissue has been shown to improve mouth odour considerably. This is accomplished by subgingival scaling and root planing and irrigation with an antibiotic mouth rinse. The bacteria that cause gingivitis and periodontal disease (periodontopathogens) are invariably gram negative and capable of producing VSC. Methyl mercaptan is known to be the greatest contributing VSC in halitosis that is caused by periodontal disease and gingivitis. The level of VSC on breath has been shown to positively correlate with the depth of periodontal pocketing, the number of pockets, and whether the pockets bleed when examined with a dental probe. Indeed, VSC may themselves have been shown to contribute to the inflammation and tissue damage that is characteristic of periodontal disease. However, not all patients with periodontal disease have halitosis, and not all patients with halitosis have periodontal disease. Although patients with periodontal disease are more likely to develop halitosis than the general population, the halitosis symptom was shown to be more strongly associated with degree of tongue coating than with the severity of periodontal disease. Another possible symptom of periodontal disease is a bad taste, which does not necessarily accompany a malodour that is detectable by others.

Other causes

Other less common reported causes from within the mouth include:[13][14][15]

- Deep carious lesions (dental decay) – which cause localized food impaction and stagnation

- Recent dental extraction sockets – fill with blood clot, and provide an ideal habitat for bacterial proliferation

- Interdental food packing – (food getting pushed down between teeth) - this can be caused by missing teeth, tilted, spaced or crowded teeth, or poorly contoured approximal dental fillings. Food debris becomes trapped, undergoes slow bacterial putrefaction and release of malodourous volatiles. Food packing can also cause a localized periodontal reaction, characterized by dental pain that is relieved by cleaning the area of food packing with interdental brush or floss.

- Acrylic dentures (plastic false teeth) – inadequate denture hygiene practises such as failing to clean and remove the prosthesis each night, may cause a malodour from the plastic itself or from the mouth as microbiota responds to the altered environment. The plastic is actually porous, and the fitting surface is usually irregular, sculpted to fit the edentulous oral anatomy. These factors predispose to bacterial and yeast retention, which is accompanied by a typical smell.

- Oral infections

- Oral ulceration

- Fasting

- Stress/anxiety

- Menstrual cycle – at mid cycle and during menstruation, increased breath VSC were reported in women.

- Smoking – Smoking is linked with periodontal disease, which is the second most common cause of oral maloduor. Smoking also has many other negative effects on the mouth, from increased rates of dental decay to premalignant lesions and even oral cancer.

- Alcohol

- Volatile foods – e.g. onion, garlic, durian, cabbage, cauliflower and radish. Volatile foodstuffs may leave malodourous residues in the mouth, which are the subject to bacterial putrefaction and VSC release. However, volatile foodstuffs may also cause halitoisis via the blood borne halitosis mechanism.

- Medication – often medications can cause xerostomia (dry mouth) which results in increased microbial growth in the mouth.

Nose and sinuses

In this occurrence, the air exiting the nostrils has a pungent odour that differs from the oral odour. Nasal odour may be due to sinus infections or foreign bodies.[7][8]

Halitosis is often stated to be a symptom of chronic rhinosinusitis, however gold standard breath analysis techniques have not been applied. Theoretically, there are several possible mechanisms of both objective and subjective halitosis that may be involved.[16]

Tonsils

There is disagreement as to the proportion of halitosis cases which are caused by conditions of the tonsils.[17] Some claim that the tonsils are the most significant cause of halitosis after the mouth.[17] According to one report, approximately 3% of halitosis cases were related to the tonsils.[17] Conditions of the tonsils which may be associated with halitosis include chronic caseous tonsillitis (cheese-like material can be exuded from the tonsillar crypt orifi), tonsillolithiasis (tonsil stones), and less commonly peritonsillar abscess, actinomycosis, fungating malignancies, chondroid choristoma and inflammatory myofibroblastic tumor.[17]

Esophagus

The lower esophageal sphincter, which is the valve between the stomach and the esophagus, may not close properly due to a hiatal hernia or GERD, allowing acid to enter the esophagus and gases to escape to the mouth. A Zenker's diverticulum may also result in halitosis due to aging food retained in the esophagus.

Stomach

The stomach is considered by most researchers as a very uncommon source of bad breath. The esophagus is a closed and collapsed tube, and continuous flow of gas or putrid substances from the stomach indicates a health problem—such as reflux serious enough to be bringing up stomach contents or a fistula between the stomach and the esophagus—which will demonstrate more serious manifestations than just foul odour.[6]

In the case of allyl methyl sulfide (the byproduct of garlic's digestion), odour does not come from the stomach, since it does not get metabolized there.

Systemic diseases

There are a few systemic (non-oral) medical conditions that may cause foul breath odour, but these are infrequent in the general population. Such conditions are:[18][19]

- Fetor hepaticus: an example of a rare type of bad breath caused by chronic liver failure.

- Lower respiratory tract infections (bronchial and lung infections).

- Kidney infections and kidney failure.

- Carcinoma.

- Trimethylaminuria ("fish odour syndrome").

- Diabetes mellitus.

- Metabolic conditions, e.g. resulting in elevated blood dimethyl sulfide.[20]

Individuals affected by the above conditions often show additional, more diagnostically conclusive symptoms than bad breath alone.

Delusional halitosis

One quarter of the people seeking professional advice on bad breath have an exaggerated concern of having bad breath, known as halitophobia, delusional halitosis, or as a manifestation of olfactory reference syndrome. They are sure that they have bad breath, although many have not asked anyone for an objective opinion. Bad breath may severely affect the lives of some 0.5–1.0% of the adult population.[21]

Diagnosis

Self diagnosis

Scientists have long thought that smelling one's own breath odour is often difficult due to acclimatization, although many people with bad breath are able to detect it in others. Research has suggested that self-evaluation of halitosis is not easy because of preconceived notions of how bad we think it should be. Some people assume that they have bad breath because of bad taste (metallic, sour, fecal, etc.), however bad taste is considered a poor indicator.

Patients often self-diagnose by asking a close friend.[22]

One popular home method to determine the presence of bad breath is to lick the back of the wrist, let the saliva dry for a minute or two, and smell the result. This test results in overestimation, as concluded from research, and should be avoided.[6] A better way would be to lightly scrape the posterior back of the tongue with a plastic disposable spoon and to smell the drying residue. Home tests that use a chemical reaction to test for the presence of polyamines and sulfur compounds on tongue swabs are now available, but there are few studies showing how well they actually detect the odour. Furthermore, since breath odour changes in intensity throughout the day depending on many factors, multiple testing sessions may be necessary.

Testing

If bad breath is persistent, and all other medical and dental factors have been ruled out, specialized testing and treatment is required. Hundreds of dental offices and commercial breath clinics now claim to diagnose and treat bad breath.[citation needed] They often use some of several laboratory methods for diagnosis of bad breath:

- Halimeter: a portable sulfide monitor used to test for levels of sulfur emissions (to be specific, hydrogen sulfide) in the mouth air. When used properly, this device can be very effective at determining levels of certain VSC-producing bacteria. However, it has drawbacks in clinical applications. For example, other common sulfides (such as mercaptan) are not recorded as easily and can be misrepresented in test results. Certain foods such as garlic and onions produce sulfur in the breath for as long as 48 hours and can result in false readings. The Halimeter is also very sensitive to alcohol, so one should avoid drinking alcohol or using alcohol-containing mouthwashes for at least 12 hours prior to being tested. This analog machine loses sensitivity over time and requires periodic recalibration to remain accurate.[23]

- Gas chromatography: portable machines are being studied.[24] This technology is designed to digitally measure molecular levels of major VSCs in a sample of mouth air (such as hydrogen sulfide, methyl mercaptan, and dimethyl sulfide). It is accurate in measuring the sulfur components of the breath and produces visual results in graph form via computer interface.

- BANA test: this test is directed to find the salivary levels of an enzyme indicating the presence of certain halitosis-related bacteria.

- β-galactosidase test: salivary levels of this enzyme were found to be correlated with oral malodour.

Although such instrumentation and examinations are widely used in breath clinics, the most important measurement of bad breath (the gold standard) is the actual sniffing and scoring of the level and type of the odour carried out by trained experts ("organoleptic measurements"). The level of odour is usually assessed on a six-point intensity scale.[4][7]

Classification

Two main classification schemes exist for bad breath, although neither are universally accepted.[3]

The Miyazaki et al. classification was originally described in 1999 in a Japanese scientific publication,[25] and has since been adapted to reflect North American society, especially with regards halitophobia.[26] The classification assumes three primary divisions of the halitosis symptom, namely genuine halitosis, pseudohalitosis and halitophobia. This classification has been suggested to be most widely used,[3] but it has been criticized because it is overly simplistic and is largely of use only to dentists rather than other specialties.

- Genuine halitosis

- A. Physiologic halitosis

- B. Pathologic halitosis

- (i) Oral

- (ii) Extra-oral

- Pseudohalitosis

- Halitophobia

The Tangerman and Winkel classification was suggested in Europe in 2002.[27][20] This classification focuses only on those cases where there is genuine halitosis, and has therefore been criticized for being less clinically useful for dentistry when compared to the Miyazaki et al. classification.

- Intra-oral halitosis

- Extra-oral halitosis

- A. Blood borne halitosis

- (i) Systemic diseases

- (ii) Metabolic diseases

- (iii) Food

- (iv) Medication

- B. Non-blood borne halitosis

- (i) Upper respiratory tract

- (ii) Lower respiratory tract

- A. Blood borne halitosis

The same authors also suggested that halitosis can be divided according to the character of the odour into 3 groups:[20]

- "Sulfurous or fecal" caused by volatile sulfur compounds (VSC), most notably methyl mercaptan, hydrogen sulfide and dimethyl sulfide.

- "Fruity" caused by acetone, present in diabetes.

- "Urine-like or ammoniacal" caused by ammonia, dimethyl amine and trimethylamine (TMA), present in trimethylaminuria and uremia.

Based on the strengths and weaknesses of previous attempts at classification, a cause based classification has been proposed:[28]

- Type 0 (physiologic)

- Type 1 (oral)

- Type 2 (airway)

- Type 3 (gastroesophageal)

- Type 4 (blood-borne)

- Type 5 (subjective)

Any halitosis symptom is potentially the sum of these types in any combination, superimposed on the physiologic odour present in all healthy individuals.[28]

Management

Approaches to improve bad breath may include physical or chemical means to decrease bacteria in the mouth, products to mask the smell, or chemicals to alter the odour creating molecules.[1] Many different interventions have been suggested and trialed such as toothpastes, mouthwashes, lasers, tongue scraping, and mouth rinses.[29] There is no strong evidence to indicate which interventions work and which are more effective.[29] It is recommended that in those who use tobacco products stop.[1] Evidence does not support the benefit of dietary changes or chewing gum.[1]

Mechanical measures

Brushing the teeth may help.[30] While there is evidence of tentative benefit from tongue cleaning it is insufficient to draw clear conclusions.[5] A 2006 Cochrane review found tentative evidence that it might decrease levels of odour molecules.[31] Flossing may be useful.[1]

Mouthwashes

A 2008 systematic review found that antibacterial mouthrinses may help.[3] Mouthwashes often contain antibacterial agents including cetylpyridinium chloride, chlorhexidine,[3] zinc gluconate, zinc chloride, zinc lactate, hydrogen peroxide, chlorine dioxide, amine fluorides, stannous fluoride, hinokitiol,[32] and essential oils.[33] Listerine is one of the well-known mouthwash products composed of different essential oils.[34] Other formulations containing herbal products and probiotics have also been proposed.[35] Cetylpyridinium chloride and chlorhexidine can temporarily stain teeth.

Underlying disease

If gum disease and cavities are present, it is recommended that these be treated.[1]

If diseases outside of the mouth are believed to be contributing to the problem, treatment may result in improvements.[1]

Counselling may be useful in those who falsely believe that they have bad breath.[1]

Epidemiology

It is difficult for researchers to make estimates of the prevalence of halitosis in the general population for several reasons. Firstly, halitosis is subject to societal taboo and stigma, which may impact individual's willingness to take part in such studies or to report accurately their experience of the condition. Secondly, there is no universal agreement about what diagnostic criteria and what detection methods should be used to define which individuals have halitosis and which do not. Some studies rely on self reported estimation of halitosis, and there is contention as to whether this is a reliable predictor of actual halitosis or not. In reflection of these problems, reported epidemiological data are widely variable.[36]

History, society and culture

The earliest known mention of bad breath occurs in ancient Egypt, where detailed recipes for toothpaste are made before the Pyramids are built. The 1550 BC Ebers Papyrus describes tablets to cure bad breath based on incense, cinnamon, myrrh and honey.[37] Hippocratic medicine advocated a mouthwash of red wine and spices to cure bad breath.[38] Alcohol-containing mouthwashes are now thought to exacerbate bad breath as they dry the mouth, leading to increased microbial growth. The Hippocratic Corpus also describes a recipe based on marble powder for females with bad breath.[39] The Ancient Roman physician Pliny wrote about methods to sweeten the breath.[40]

Ancient Chinese emperors required visitors to chew clove before an audience.[37] The Talmud describes bad breath as a disability, which could be grounds for legal breaking of a marriage license.[13] Early Islamic theology stressed that the teeth and tongue should be cleaned with a siwak, a stick from the plant Salvadora persica tree.[13] This traditional chewing stick is also called a Miswak, especially used in Saudi Arabia, an essentially is like a natural toothbrush made from twigs.[37] During the Renaissance era, Laurent Joubert, doctor to King Henry III of France states bad breath is "caused by dangerous miasma that falls into the lungs and through the heart, causing severe damages".[37]

In B. G. Jefferis and J. L. Nichols' "Searchlights on Health" (1919), the following recipe is offered: "[One] teaspoonful of the following mixture after each meal: One ounce chloride of soda, one ounce liquor of potassa, one and one-half ounces phosphate of soda, and three ounces of water."

In the present day, bad breath is one of the biggest social taboos. The general population places great importance on the avoidance of bad breath, illustrated by the annual $1 billion that consumers in the United States spend on deodorant-type mouth (oral) rinses, mints, and related over-the-counter products.[14] Many of these practices are merely short term attempts at masking the odour. Some authors have suggested that there is an evolutionary basis to concern over bad breath. An instinctive aversion to unpleasant odours may function to detect spoiled food sources and other potentially invective or harmful substances.[41] Body odours in general are thought to play an important role in mate selection in humans,[42] and unpleasant odour may signal disease, and hence a potentially unwise choice of mate. Although reports of bad breath are found in the earliest medical writings known, the social stigma has likely changed over time, possibly partly due to sociocultural factors involving advertising pressures. As a result, the negative psychosocial aspects of halitosis may have worsened, and psychiatric conditions such as halitophobia are probably more common than historically. There have been rare reports of people committing suicide because of halitosis, whether there is genuine halitosis or not.

Etymology

The word halitosis is derived from the Latin word halitus, meaning 'breath', and the Greek suffix -osis meaning 'diseased' or 'a condition of'.[43] With modern consumerism, there has been a complex interplay of advertising pressures and the existing evolutionary aversion to malodour. Contrary to the popular belief that Listerine coined the term halitosis, its origins date to before the product's existence,[44] being coined by physician Joseph William Howe in his 1874 book The Breath, and the Diseases Which Give It a Fetid Odor,[45][46] although it only became commonly used in the 1920s when a marketing campaign promoted Listerine as a solution for "chronic halitosis". The company was the first to manufacture mouth washes in the United States. According to Freakonomics:

Listerine "...was invented in the nineteenth century as powerful surgical antiseptic. It was later sold, in distilled form, as both a floor cleaner and a cure for gonorrhea. But it wasn't a runaway success until the 1920s, when it was pitched as a solution for "chronic halitosis"— a then obscure medical term for bad breath. Listerine's new ads featured forlorn young women and men, eager for marriage but turned off by their mate's rotten breath. "Can I be happy with him in spite of that?" one maiden asked herself. Until that time, bad breath was not conventionally considered such a catastrophe, but Listerine changed that. As the advertising scholar James B. Twitchell writes, "Listerine did not make mouthwash as much as it made halitosis." In just seven years, the company's revenues rose from $115,000 to more than $8 million."[47]

Alternative medicine

According to traditional Ayurvedic medicine, chewing areca nut and betel leaf is a remedy for bad breath.[48] In South Asia, it was a custom to chew areca or betel nut and betel leaf among lovers because of the breath-freshening and stimulant drug properties of the mixture. Both the nut and the leaf are mild stimulants and can be addictive with repeated use. The betel nut will also cause dental decay and red or black staining of teeth when chewed.[49] Both areca nut and betel leaf chewing, however, can cause premalignant lesions such as leukoplakia and submucous fibrosis, and are recognized risk factors for oral and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (oral cancer).[50]

Practitioners and purveyors of alternative medicine sell a vast range of products that claim to be beneficial in treating halitosis, including dietary supplements, vitamins, and oral probiotics. Halitosis is often claimed to be a symptom of "candida hypersensitivity syndrome" or related diseases, and is claimed to be treatable with antifungal medications or alternative medications to treat fungal infections.

Research

In 1996, the International Society for Breath Odor Research (ISBOR) was formed to promote multidisciplinary research on all aspects of breath odours.

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z Kapoor, U; Sharma, G; Juneja, M; Nagpal, A (2016). "Halitosis: Current concepts on etiology, diagnosis and management". European Journal of Dentistry. 10 (2): 292–300. doi:10.4103/1305-7456.178294. PMC 4813452. PMID 27095913.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ a b c d e f g Harvey-Woodworth, CN (April 2013). "Dimethylsulphidemia: the significance of dimethyl sulphide in extra-oral, blood borne halitosis". British Dental Journal. 214 (7): E20. doi:10.1038/sj.bdj.2013.329. PMID 23579164.

- ^ a b c d e f Fedorowicz, Z; Aljufairi, H; Nasser, M; Outhouse, TL; Pedrazzi, V (Oct 8, 2008). Fedorowicz, Zbys (ed.). "Mouthrinses for the treatment of halitosis". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4): CD006701. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006701.pub2. PMID 18843727. (Retracted, see doi:10.1002/14651858.cd006701.pub3)

- ^ a b c d Loesche, WJ; Kazor, C (2002). "Microbiology and treatment of halitosis". Periodontology 2000. 28: 256–79. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0757.2002.280111.x. PMID 12013345.

- ^ a b Van der Sleen, Mi; Slot, De; Van Trijffel, E; Winkel, Eg; Van der Weijden, Ga (2010-11-01). "Effectiveness of mechanical tongue cleaning on breath odour and tongue coating: a systematic review". International Journal of Dental Hygiene. 8 (4): 258–268. doi:10.1111/j.1601-5037.2010.00479.x. ISSN 1601-5037. PMID 20961381.

- ^ a b c Rosenberg, M (2002). "The science of bad breath". Scientific American. 286 (4): 72–9. Bibcode:2002SciAm.286d..72R. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0402-72. PMID 11905111.

- ^ a b c Rosenberg, M (1996). "Clinical assessment of bad breath: Current concepts". Journal of the American Dental Association. 127 (4): 475–82. doi:10.14219/jada.archive.1996.0239. PMID 8655868.

- ^ a b Scully C, Rosenberg M. Halitosis. Dent Update. 2003 May;3

- ^ Zalewska, A; Zatoński, M; Jabłonka-Strom, A; Paradowska, A; Kawala, B; Litwin, A (September 2012). "Halitosis--a common medical and social problem. A review on pathology, diagnosis and treatment". Acta Gastro-enterologica Belgica. 75 (3): 300–9. PMID 23082699.

- ^ Bosy, A (1997). "Oral malodor: Philosophical and practical aspects". Journal (Canadian Dental Association). 63 (3): 196–201. PMID 9086681.

- ^ Nachnani, S (2011). "Oral malodor: Causes, assessment, and treatment". Compendium of Continuing Education in Dentistry. 32 (1): 22–4, 26–8, 30–1, quiz 32, 34. PMID 21462620.

- ^ "Scientists find bug responsible for bad breath". Reuters. April 7, 2008. Archived from the original on May 29, 2010.

- ^ a b c Winkel EG (2008). "Chapter 60: Halitosis Control". In Lindhe J, Lang NP, Karring T (eds.). Clinical periodontology and implant dentistry (5th ed.). Oxford: Blackwell Munksgaard. pp. 1324–1340. ISBN 978-1405160995.

- ^ a b Quirynen M, Van den Velde S, Vandekerckhove B, Dadamio J (2012). "Chapter 29: Oral Malodor". In Newman MG, Takei HH, Klokkevold PR, Carranza FA (eds.). Carranza's clinical periodontology (11th ed.). St. Louis, Mo.: Elsevier/Saunders. pp. 331–338. ISBN 978-1-4377-0416-7.

- ^ Scully, Crispian (2008). Oral and maxillofacial medicine : the basis of diagnosis and treatment (2nd ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. ISBN 978-0443068188.

- ^ Ferguson, M (May 23, 2014). "Rhinosinusitis in oral medicine and dentistry". Australian Dental Journal. 59 (3): 289–295. doi:10.1111/adj.12193. PMID 24861778.

- ^ a b c d Ferguson, M; Aydin, M; Mickel, J (Aug 5, 2014). "Halitosis and the Tonsils: A Review of Management". Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. 151 (4): 567–74. doi:10.1177/0194599814544881. PMID 25096359. S2CID 39801742.

- ^ Tangerman, A (2002). "Halitosis in medicine: A review". International Dental Journal. 52 Suppl 3 (5): 201–6. doi:10.1002/j.1875-595x.2002.tb00925.x. PMID 12090453.

- ^ Tonzetich, J (1977). "Production and origin of oral malodor: A review of mechanisms and methods of analysis". Journal of Periodontology. 48 (1): 13–20. doi:10.1902/jop.1977.48.1.13. PMID 264535.

- ^ a b c Tangerman, A; Winkel, EG (March 2010). "Extra-oral halitosis: an overview". Journal of Breath Research. 4 (1): 017003. doi:10.1088/1752-7155/4/1/017003. PMID 21386205. S2CID 5342660.

- ^ Lochner, C; Stein, DJ (2003). "Olfactory reference syndrome: Diagnostic criteria and differential diagnosis". Journal of Postgraduate Medicine. 49 (4): 328–31. PMID 14699232.

- ^ Eli, I; Baht, R; Koriat, H; Rosenberg, M (2001). "Self-perception of breath odor". Journal of the American Dental Association. 132 (5): 621–6. doi:10.14219/jada.archive.2001.0239. PMID 11367966.

- ^ Rosenberg, M; McCulloch, CA (1992). "Measurement of oral malodor: Current methods and future prospects". Journal of Periodontology. 63 (9): 776–82. doi:10.1902/jop.1992.63.9.776. PMID 1474479.

- ^ Andreas Filippi,"Halitosis- a review". Oralprophylaxe & Kinderzahnheilkunde 31 (2009) 4: 173-174.

- ^ Miyazaki, H; Arao, M; Okamura, K; Kawaguchi, Y; Toyofuku, A; Hoshi, K; Yaegaki, K. (1999). "[Tentative classification of halitosis and its treatment needs] (Japanese)". Niigata Dental Journal. 32: 7–11.

- ^ Yaegaki, K; Coil, JM (May 2000). "Examination, classification, and treatment of halitosis; clinical perspectives". Journal (Canadian Dental Association). 66 (5): 257–61. PMID 10833869. Archived from the original on 2013-05-16.

- ^ Tangerman, A (June 2002). "Halitosis in medicine: a review". International Dental Journal. 52 Suppl 3: 201–6. doi:10.1002/j.1875-595x.2002.tb00925.x. PMID 12090453.

- ^ a b Aydin, M; Harvey-Woodworth, CN (11 July 2014). "Halitosis: a new definition and classification". British Dental Journal. 217 (1): E1. doi:10.1038/sj.bdj.2014.552. PMID 25012349.

- ^ a b Kumbargere Nagraj, Sumanth; Eachempati, Prashanti; Uma, Eswara; Singh, Vijendra Pal; Ismail, Noorliza Mastura; Varghese, Eby (2019). "Interventions for managing halitosis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 12: CD012213. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012213.pub2. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 6905014. PMID 31825092.

- ^ "Bad breath - Diagnosis and treatment - Mayo Clinic". www.mayoclinic.org. Retrieved 19 January 2018.

- ^ Outhouse, TL; Al-Alawi, R; Fedorowicz, Z; Keenan, JV (19 April 2006). Outhouse, Trent L (ed.). "Tongue scraping for treating halitosis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2): CD005519. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005519.pub2. PMID 16625641. (Retracted, see doi:10.1002/14651858.cd005519.pub3)

- ^ Iha, Kosaku; Suzuki, Nao; Yoneda, Masahiro; Takeshita, Toru; Hirofuji, Takao (October 2013). "Effect of mouth cleaning with hinokitiol-containing gel on oral malodor: a randomized, open-label pilot study". Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology and Oral Radiology. 116 (4): 433–439. doi:10.1016/j.oooo.2013.05.021. PMID 23969334.

- ^ Scully, C (18 September 2014). "Halitosis". BMJ Clinical Evidence. 2014. PMC 4168334. PMID 25234037.

- ^ Newton, David (2008). Trademarked: a history of well-known brands, from Aertex to Wright's Coal Tar. Stroud: Sutton Publishing. ISBN 978-0750945905.

- ^ Prasad, Monika (2016). "The Clinical Effectiveness of Post- Brushing Rinsing in Reducing Plaque and Gingivitis: A Systematic Review". Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research. 10 (5): ZE01-7. doi:10.7860/JCDR/2016/16960.7708. PMC 4948552. PMID 27437376.

- ^ Cortelli, JR; Barbosa, MD; Westphal, MA (2008). "Halitosis: a review of associated factors and therapeutic approach". Brazilian Oral Research. 22 Suppl 1: 44–54. doi:10.1590/s1806-83242008000500007. PMID 19838550.

- ^ a b c d Tayara, Rafif; Riad Bacho. "Bad breath: What's The Story?". Archived from the original on 24 March 2013. Retrieved 13 August 2012.

- ^ Hippocratic Corpus

- ^ Rosenberg, Mel, ed. (1998). Bad breath : research perspectives (2. ed.). Tel Aviv: Ramot Publishing. ISBN 978-9652741738.

- ^ Eggert, F-Michael. "Bad Breath is an Ancient Concern!". Archived from the original on 5 November 2013. Retrieved 13 August 2012.

- ^ Hoover, KC (2010). "Smell with inspiration: the evolutionary significance of olfaction". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 143 Suppl 51: 63–74. doi:10.1002/ajpa.21441. PMID 21086527.

- ^ Grammer, K; Fink, B; Neave, N (Feb 1, 2005). "Human pheromones and sexual attraction". European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Biology. 118 (2): 135–42. doi:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2004.08.010. PMID 15653193.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "halitosis". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ Halitosis – Definition and More from the Free Merriam-Webster Dictionary Archived 2011-11-15 at the Wayback Machine. Merriam-webster.com. Retrieved on 2011-10-10

- ^ Howe, Joseph W. (1874). The Breath, and the Diseases Which Give It a Fetid Odor. New York: D. Appleton & Company. p. 20.

- ^ Katz, Harold (January 12, 2011). "The Origin and Evolution of". Therabreath. Archived from the original on November 25, 2016. Retrieved 2016-11-24.

- ^ Levitt, Steven D.; Dubner, Stephen J. (2009). Freakonomics : A Rogue Economist Explores The Hidden Side Of Everything. New York: HarperCollins. p. 87. ISBN 978-0-06-073133-5. OCLC 502013083. Archived from the original on 2011-02-13.

- ^ Naveen Pattnaik, The Tree of Life

- ^ Norton, SA (January 1998). "Betel: consumption and consequences". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 38 (1): 81–8. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(98)70543-2. PMID 9448210.

- ^ Warnakulasuriya, S; Trivedy, C; Peters, TJ (Apr 6, 2002). "Areca nut use: an independent risk factor for oral cancer". BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 324 (7341): 799–800. doi:10.1136/bmj.324.7341.799. PMC 1122751. PMID 11934759.