German aircraft carrier Graf Zeppelin

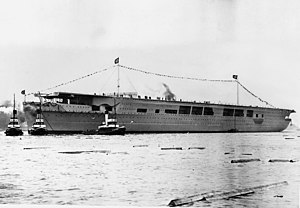

Graf Zeppelin after her launching on 8 December 1938

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Graf Zeppelin |

| Namesake | Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin |

| Builder | Deutsche Werke, Kiel Shipyards |

| Laid down | 28 December 1936 |

| Launched | 8 December 1938 |

| Fate | Sunk as a target ship on 16 August 1947 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | Graf Zeppelin-class aircraft carrier |

| Displacement | 33,550 long tons (34,088 t) (full load) |

| Length | 262.5 m (861 ft 3 in) |

| Beam | 36.2 m (118 ft 9 in) |

| Draft | 8.5 m (27 ft 11 in) |

| Installed power | 200,000 shaft horsepower (150,000 kW) |

| Propulsion | 4 geared turbines |

| Speed | 33.8 knots (62.6 km/h; 38.9 mph) |

| Range | 8,000 nmi (15,000 km; 9,200 mi) at 19 knots (35 km/h; 22 mph) |

| Complement | 1,720 |

| Armament |

|

| Armor |

|

| Aircraft carried |

|

The German aircraft carrier Graf Zeppelin was the lead ship in a class of two carriers of the same name ordered by the Kriegsmarine of Nazi Germany. She was the only aircraft carrier launched by Germany and represented part of the Kriegsmarine's attempt to create a well-balanced oceangoing fleet, capable of projecting German naval power far beyond the narrow confines of the Baltic and North Seas. The carrier would have had a complement of 42 fighters and dive bombers.

Construction on Graf Zeppelin began on 28 December 1936, when her keel was laid down at the Deutsche Werke shipyard in Kiel. Named in honor of Graf (Count) Ferdinand von Zeppelin, the ship was launched on 8 December 1938, and was 85% complete by the outbreak of World War II in September 1939. Graf Zeppelin was not completed and was never operational due to shifting construction priorities necessitated by the war. She remained in the Baltic for the duration of the war; with Germany's defeat imminent, the ship's custodian crew scuttled her just outside Stettin in March 1945. The Soviet Union raised the ship in March 1946, and she was ultimately sunk in weapons tests north of Poland 17 months later. The wreck was discovered by a Polish survey ship in July 2006.

Design

Graf Zeppelin was 262.5 meters (861 ft) long overall; she had a beam of 36.2 m (119 ft) and a maximum draft of 8.5 m (28 ft). At full combat load, she would have displaced 33,550 long tons (34,090 t). The ship's propulsion system consisted of four Brown, Boveri & Cie geared turbines with sixteen oil-fired, ultra-high-pressure LaMont boilers. The power plant was rated at 200,000 shaft horsepower (150 MW) and a top speed of 33.8 knots (62.6 km/h; 38.9 mph). Graf Zeppelin had a projected cruising radius of 8,000 nautical miles (15,000 km; 9,200 mi) at a speed of 19 kn (35 km/h; 22 mph). She would have had a crew of 1760 officers and enlisted men, plus flight crews.[2]

The ship's primary offensive power would have been its aircraft complement. Graf Zeppelin would have carried 42 aircraft as designed: 12 navalized Junkers Ju 87 "Stuka" dive bombers, 10 Messerschmitt Bf 109 fighters, and 20 Fieseler Fi 167 torpedo bombers.[3] Later during the construction process, the aerial complement was reworked to consist of thirty Ju 87s and twelve Bf 109s, and the Fi 167s were removed altogether. As designed, Graf Zeppelin was to be fitted with eight 15 cm SK C/28 guns for defense against surface warships. This number was later increased to sixteen. Her anti-aircraft battery consisted of ten 10.5 cm SK C/33 guns—later increased to twelve—twenty-two 3.7 cm SK C/30 guns, and twenty-eight 2 cm guns. The ship's flight deck was protected with up to 45 millimeters (1.8 in) of Wotan Weich steel armor.[a] A 60 mm-thick (2.4 in) armored deck was located under the deck to protect the ship's vitals from aerial attacks. Graf Zeppelin had a waterline armor belt that was 100 mm (3.9 in) thick in the central area of the ship.[2]

Construction and cancellation

On 16 November 1935, the contract for Flugzeugträger A (Aircraft carrier A)—later christened Graf Zeppelin—was awarded to the Deutsche Werke shipyard in Kiel. Construction of the ship was delayed since Deutsche Werke was working at capacity, and the slipway needed for Graf Zeppelin was occupied by the new battleship Gneisenau, which was launched on 8 December 1936.[5] Work started on Graf Zeppelin on 28 December, when her keel was laid down. She was launched on 8 December 1938, the 24th anniversary of the Battle of the Falkland Islands,[6] and she was christened by Helene von Zeppelin, the daughter of the ship's namesake. At the launching ceremony, Hermann Göring gave a speech.[7] By the end of 1939, she was 85% complete, with a projected completion by the middle of 1940.[8] By September 1939, one carrier-borne wing, Trägergruppe 186, had been formed by the Luftwaffe at Kiel Holtenau, composed of three squadrons equipped with Bf 109s and Ju 87s.[9]

Meanwhile, the German conquest of Norway in April 1940 eroded any chance of completing Graf Zeppelin. Now responsible for defending Norway's long coastline and numerous port facilities, the Kriegsmarine urgently needed large numbers of coastal guns and anti-aircraft batteries. During a naval conference with Hitler on 28 April 1940, Admiral Erich Raeder proposed halting all work on Graf Zeppelin, arguing that even if she was commissioned by the end of 1940, final installation of her guns would need another ten months or more (her original fire-control system had been sold to the Soviet Union under an earlier trade agreement).[10] Hitler consented to the stop work order, allowing Raeder to have Graf Zeppelin's 15 cm guns removed and transferred to Norway. The carrier's heavy flak armament of twelve 10.5 cm guns had already been diverted elsewhere.[11]

In July 1940, Graf Zeppelin was towed from Kiel to Gotenhafen (Gdynia) and remained there for nearly a year. While there, she was used as a storage depot for Germany's hardwood supply.[12] Just before Germany invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941, the carrier was again moved, this time to Stettin, to safeguard her from Soviet air attacks. By November, the German army had pushed deep enough into Russian territory to remove any further threat of air attack and Graf Zeppelin was returned to Gotenhafen. There, she was used as a store ship for timber.[13]

By the time Raeder met with Hitler for a detailed discussion of naval strategy in April 1942, the usefulness of aircraft carriers in modern naval warfare had been amply demonstrated. British carriers had crippled the Italian fleet at Taranto in November 1940, critically damaged the German battleship Bismarck in May 1941 and prevented the battleship Tirpitz from attacking two convoys bound for Russia in March 1942. In addition, a Japanese carrier raid on Pearl Harbor had devastated the American battle fleet in December 1941. Raeder, anxious to secure air protection for the Kriegsmarine's heavier surface units, informed Hitler that Graf Zeppelin could be finished in about a year, with another six months required for sea trials and flight training. On 13 May 1942, with Hitler's authorization, the German Naval Supreme Command ordered work resumed on the carrier.[14]

But daunting technical problems remained. Raeder wanted newer planes, specifically designed for carrier use. Reichsmarshall Hermann Göring, head of the Luftwaffe, replied that the already overburdened German aircraft industry could not possibly complete the design, testing and mass production of such aircraft before 1946. Instead, he proposed converting existing aircraft (again the Junkers Ju 87 and Messerschmitt Bf 109) as a temporary solution until newer types could be developed. Training of carrier pilots at Travemünde would also resume.[14]

The converted carrier aircraft were heavier versions of their land-based predecessors and this required a host of changes to Graf Zeppelin's original design: the existing catapults needed modernization; stronger winches were necessary for the arresting gear; the flight deck, elevators and hangar floors also required reinforcement.[15] Changes in naval technology dictated other alterations as well: installation of air search radar sets and antennas; upgraded radio equipment; an armored fighter-director cabin mounted on the main mast (which in turn meant a heavier, sturdier mast to accommodate the cabin's added weight); extra armoring for the bridge and fire control center; a new curved funnel cap to shield the fighter-director cabin from smoke; replacing the single-mount 20mm AA guns with quadruple Flakvierling 38 guns (with a corresponding increase in ammunition supply) to improve overall AA defense; and additional bulges on either side of the hull to preserve the ship's stability under all this added weight.[16]

The German naval staff hoped all these changes could be accomplished by April 1943, with the carrier's first sea trials taking place in August that year. Towards that end, Chief Engineer Wilhelm Hadeler was reassigned to oversee Graf Zeppelin's completion. Hadeler planned on getting the two inner shafts and their respective propulsion systems operational first, giving the ship an initial speed of 25–26 knots, fast enough for sea trials to commence and for conducting air training exercises. By the winter of 1943–1944 she was expected to be combat-ready.[14]

On the night of 27–28 August 1942, while still moored at Gotenhafen, Graf Zeppelin was the target of the only Allied air attack aimed at her during the war. Three Royal Air Force Avro Lancaster heavy bombers from 106 Squadron were dispatched against the German aircraft carrier, each one carrying a single "Capital Ship" bomb, a 5,600 lb (2,540 kg) device with a shaped charge warhead intended for armored targets.[17] One pilot, who was unable to see the carrier due to haze, dropped his bomb instead on the estimated position of the German battleship Gneisenau. Another believed he had scored a direct hit on Graf Zeppelin, but there is no known record of the ship suffering any damage from a bomb strike that night.[18]

On 5 December 1942, Graf Zeppelin was towed back to Kiel and placed in a floating drydock. It seemed she might well see completion after all, but by late January 1943 Hitler had become so disenchanted with the Kriegsmarine, especially with what he perceived as the poor performance of its surface fleet, that he ordered all of its larger ships taken out of service and scrapped. Raeder was relieved of command shortly thereafter and replaced with the Commander of Submarines Karl Dönitz. Though Admiral Dönitz eventually persuaded Hitler to void most of the order, work on all new surface ships and even those nearing completion, including Graf Zeppelin, was halted.[19][20] On 30 January 1943, all major work on the ship ceased, though some limited, temporary work continued until March.[12]

In April 1943 Graf Zeppelin was again towed eastward, first to Gotenhafen, then to the roadstead at Swinemünde and finally berthed at a back-water wharf in the Parnitz River, two miles (3 km) from Stettin, where she had been briefly docked in 1941. There she languished for the next two years with only a 40-man custodial crew in attendance.[21] When Red Army forces neared the city in April 1945, the ship's Kingston valves were opened, flooding her lower spaces and settling her firmly into the mud in shallow water. A ten-man engineering squad then rigged the vessel's interior with demolition and depth charges in order to hole the hull and destroy vital machinery. At 6pm on 25 April 1945, just as the Soviets entered Stettin, commander Wolfgang Kähler radioed the squad to detonate the explosives. Smoke billowing from the carrier's funnel confirmed the charges had gone off, rendering the ship useless to her new owners for many months to come.[22]

Fate after the war

The carrier's history and fate after Germany's surrender was unknown outside the Soviet Union for decades after the war. The Soviets could not repair the ship in the length of time specified by the terms of the Allied Tripartite Commission, so she was designated a "Category C" ship. This classification required that she would be destroyed or sunk in deep water by 15 August 1946.[23] Instead, the Soviets decided to salvage the damaged ship and it was refloated in March 1946. A number of speculations from Western historians about the ship's fate arose in the decades after the end of the war. According to German historian Erich Gröner, after the Soviets raised the scuttled ship, they towed her to Leningrad. While en route, she reportedly struck a mine off Finland during a storm. Gröner claimed that after arriving in Leningrad, Graf Zeppelin was broken up for scrap in 1948–1949.[12] Naval historians Robert Gardiner and Roger Chesneau state that the ship was towed out of Stettin in September 1947, but she never arrived in Leningrad; they speculated that a mine sank the ship while she was under tow.[8]

According to Soviet records, on 19 March 1947, the Council of Ministers decreed the destruction of former German ships. The first ship to be sunk, Lützow, was sunk off Swinemunde on 22 July 1947. On 14 August Graf Zeppelin was towed into Swinemunde harbor, and two days later to its final position. It was subjected to five series of controlled explosions of 180 mm (7.1 in) shells and FAB series bombs. The first test imitated a FAB-1000 detonation in the exhaust funnel and lesser bombs below the flight deck. The second in the series was a single FAB-1000 explosion above the flight deck. The third, the fourth and the fifth series imitated penetration of FAB-100, FAB-250 and FAB-500 bombs at flight deck, hangar deck and gun battery deck levels. These bombs were placed in cutouts in their target decks to imitate the effects of dive bombing. Graf Zeppelin remained afloat, and Admiral Yury Rall ordered a torpedo strike. A torpedo fired from an Elco PT boat exploded in the anti-torpedo bulge but did not penetrate the belt armor. A torpedo fired by the destroyer Slavny penetrated the unprotected hull section below the bow elevator; Graf Zeppelin sank 25 minutes later.[24]

Discovery in 2006

The exact position of the wreck was unknown for decades. On 12 July 2006, the research vessel RV St. Barbara, a ship belonging to the Polish oil company Petrobaltic, found a 265-meter-long (869 ft) wreck 55 km (34 mi) north of Władysławowo, which they thought was most likely Graf Zeppelin. The wreck rests at a depth of more than 80 m (260 ft) below the surface. After the wreck was located, the Polish Navy began a two-day survey of the wreckage to confirm its identity. Using remote-controlled underwater robots, they concluded that they were "99% certain" it was Graf Zeppelin.[25][26]

Notes

Footnotes

Citations

- ^ a b c Chesneau, pp. 76–77

- ^ a b Gröner, p. 71

- ^ Reynolds, p. 44

- ^ Gröner, p. x

- ^ Breyer, p. 11

- ^ Gardiner & Chesneau, p. 226

- ^ Israel, pp. 67–69

- ^ a b Gardiner & Chesneau, p. 227

- ^ Whitley (1984), p. 164

- ^ Schenk, p. 143

- ^ Whitley (1985), p. 30

- ^ a b c Gröner, p. 72

- ^ Schenk, p. 157

- ^ a b c Reynolds, p. 47

- ^ Barker, p. 283

- ^ Whitley (1985), p. 31

- ^ Lake, p. 50

- ^ Marshall, p. 21

- ^ Mann & Jörgensen, pp. 139–141

- ^ Whitley (1985), p. 32

- ^ Reynolds, p. 48

- ^ Kuzin & Litinskii, p. 161

- ^ Rohwer & Monakov, p. 199

- ^ Shirokorad, pp. 108–112.

- ^ "'Nazi aircraft carrier' located". BBC News. 28 July 2006.

- ^ Boyes, Roger (27 July 2006). "Divers find Hitler's aircraft carrier". The Times. Retrieved 2 June 2013.

References

- Barker, Lt. Cmdr Edward L. (March 1954). "War Without Aircraft Carriers". Proceedings. Annapolis: United States Naval Institute Proceedings. OCLC 61522996.

- Burke, Stephen (Sep 2007). Without Wings: The Story of Hitler's Aircraft Carrier. Victoria: Trafford Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4251-2216-4.

- Breyer, Siegfried (1989). Graf Zeppelin: The German Aircraft Carrier. Atglen: Schiffer Publishing Ltd. ISBN 0887402429.

- Chesneau, Roger (1998). Aircraft Carriers of the World, 1914 to the Present An Illustrated Encyclopedia. London: Brockhampton Press. p. 288. ISBN 1-86019-875-9.

- Gröner, Erich (1990). German Warships: 1815–1945. Vol. I: Major Surface Vessels. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-790-6.

- Israel, Ulrich H.-J. (1994). Graf Zeppelin: Einziger Deutscher Flugzeugträger. Hamburg: Verlag Koehler/Mittler. ISBN 3782206029.

- Kuzin, V. P.; Litinskii, D. Iu. (2008). "Avianosets "Graf Zeppelin"—boevoi trofei Krasnoi Armii [Aircraft Carrier Graf Zeppelin—Battle Trophy of the Red Army]". Warship International. 45 (2). Toledo: International Naval Research Organization: 161–165. ISSN 0043-0374. OCLC 1647131.

- Lake, Jon (2002). Lancaster Squadrons 1942-43. Oxford: Osprey. ISBN 1-84176-313-6.

- Mann, Chris & Jörgensen, Christer (2003). Hitler's Arctic War: the German campaigns in Norway, Finland, and the USSR, 1940–1945. New York: Thomas Dunne Books. ISBN 978-0-312-31100-1.

- Marshall, Francis L. (1994). Sea Eagles: The Operational History of the Messerschmitt Bf 109T. Walton on Thames: Air Research Publications. ISBN 1871187230.

- Reynolds, Clark G. (January 1967). "Hitler's Flattop: The End of the Beginning". Proceedings. United States Naval Institute Proceedings. OCLC 61522996.

- Rohwer, Jürgen & Monakov, Mikhail S. (2001). Stalin's Ocean-going Fleet. London: Frank Cass. ISBN 0714648957.

- Schenk, Peter (2008). "German Aircraft Carrier Developments". Warship International. 45 (2). Toledo: International Naval Research Organization: 129–158. ISSN 0043-0374. OCLC 1647131.

- Shirokorad, Alexander (2004). Флот, который уничтожил Хрущёв (Flot, kotoryi unichtozhil Khruschev (in Russian). Moscow: AST publishers. ISBN 5-9602-0027-9.

- Whitley, M.J. (July 1984). Warship 31: Graf Zeppelin, Part 1. Vol. VIII. Annapolis: United States Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-85177-354-0.

- Whitley, M.J. (1985). Warship 33: Graf Zeppelin, Part 2. Vol. IX. Annapolis: United States Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-984-7.

Further reading

- Willigenburg, Henk van (March–April 2001). "Graft Zeppelin Afloat". Air Enthusiast (92): 59–65. ISSN 0143-5450.

External links

- Graf Zeppelin-class aircraft carriers

- World War II aircraft carriers of Germany

- Shipwrecks in the Baltic Sea

- Proposed aircraft carriers

- Germany–Soviet Union relations

- 1938 ships

- Maritime incidents in April 1945

- Maritime incidents in 1947

- Ships sunk as targets

- Proposed ships of Germany

- Ships built in Kiel

- Shipwrecks of Poland