Dame Street

Dame Street, Dublin | |

| Native name | Sráid an Dáma (Irish) |

|---|---|

| Namesake | A medieval dam on the River Poddle |

| Length | 300 m (980 ft) |

| Width | 20 metres (66 ft) |

| Postal code | D02 |

| Coordinates | 53°20′39″N 6°15′53″W / 53.34417°N 6.26472°W |

| west end | Cork Hill, outside City Hall |

| east end | College Green |

| Other | |

| Known for | banks, restaurants |

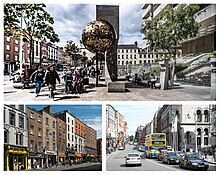

Dame Street (/ˈdeɪm/; Irish: Sráid an Dáma) is a large thoroughfare in Dublin, Ireland.

History

The street takes its name from a dam built across the River Poddle to provide water power for milling.[1][2] First appears in records under this name around 1610 but in the 14th century was also known as "the street of Theng-mote" or Teyngmouth Street.[3] It appears later as Dammastrete and Damask-street. There was a medieval church of St. Mary del Dam which was demolished in the seventeenth century. Sir Maurice Eustace, Lord Chancellor of Ireland 1660–1665, built his townhouse, Damask, on the site.[4] There was a side street called Dame's-gate, also known as the gate of S. Mary, which was adjoining St. Mary del Dam church, recorded in 1552 and demolished in 1698.[3] The street was widened by the Wide Streets Commission in 1769, and developed into the city's financial centre.[2]

Among the notable residents was Francesco Geminiani, whose house on Dame Street had a concert hall attached.[5] Unlike O'Connell Street and other previously fashionable streets, Dame Street continued to remain fashionable and prosperous after the Act of Union in 1801.[6]

Location

During the day, the street is busy, due to its central location in the city. It is a five-minute walk to the shopping area of Grafton Street and ten minutes from O'Connell Street. The Temple Bar area of the city is located directly north of the street. Daly's Club was founded in the 1750s at numbers 1-3 Dame Street and remained there until 1791, when it moved to College Green.[7]

Architecture

The former Central Bank of Ireland headquarters, now known as Central Plaza, on Dame Street was built in 1975. It was initially higher than planning permission allowed, though this was retrospectively rectified.[8] The new building was built on a parcel of land on which was a collection of Victorian and Georgian buildings including the Commercial Buildings. The Commercial Buildings dated from 1796, and were associated with the Ouzel Galley Society. This building also featured a paved courtyard which served as a pedestrian shortcut between Merchant's Arch and the Ha'penny Bridge beyond. Initially, planners wanted the facade of the building retained, but it was discarded, and eventually, a replica was constructed in the scheme. Commenting on the scheme in September 1972, Architects' Journal stated that the proposed building was "an exercise in how to do the greatest urban damage".[9] The Bank left the premises in March 2017, and moved to North Wall Quay.[10]

In comparison, Northern Bank, retained the Italianate headquarters of the Hibernian Bank both the exterior and interior, with redevelopment taking place behind the streetscape.[11] The Allied Irish Banks opposite the Olympia Theatre was designed by Thomas Deane in 1872 for the Munster & Leinster Bank and is based on the design of the Museum Building at Trinity College. The glass and cast iron canopy of the Olympia Theatre which extends out over the footpath is a prominent landmark on the street.[2] The Montague Burton Building is a notable example of the Art Deco style on Dame Street, situated on the corner with South Great George's Street. It was constructed between 1929 and 1930 and designed by architect Harry Wilson.[12] The ground level retail unit of this building is a large Spar shop and delicatessen. Due to its proximity to the gay pub and venue, The George, this Spar became known colloquially as the "Gay Spar".[13][14] During the 2022 Pride celebrations in Dublin, the Spar officially adopted the name when it "came out" as the Gay Spar.[15][16]

The street features a modern square, Barnardos Square in front of Dublin Castle and to the side of City Hall. The site had been occupied by a row of shops, one of which was the birthplace of the square's namesake, Thomas John Barnardo.[17] Before its redevelopment, the site had been cleared of the Georgian terrace of buildings which were demolished in the mid-1970s as part of a road-widening development. One of the surviving buildings from the block is the headquarters of the Sick and Indigent Roomkeepers' Society. In the 1980s there was a proposal to create a park on the site.[18]

Occupy protests

The Occupy Dame Street protest began in October 2011 directly outside the then headquarters of the Central Bank of Ireland, as part of the global Occupy movement, and lasted until March 2012.[19][20][21]

See also

References

Notes

- ^ Casey 2005, p. 414.

- ^ a b c Clerkin, Paul (2001). Dublin street names. Dublin: Gill & Macmillan. pp. 53–54. ISBN 0-7171-3204-8. OCLC 48467800.

- ^ a b M'Cready, C. T. (1987). Dublin street names dated and explained. Blackrock, Co. Dublin: Carraig. p. 29. ISBN 1-85068-005-1. OCLC 263974843.

- ^ Somerville-Woodward, Robert and Morris, Nicola "17 Eustace Street-a history" Timeline Research Ltd. 2007

- ^ Maxwell 1997, p. 121.

- ^ Maxwell 1997, p. 299.

- ^ T. H. S. Escott, Club Makers and Club Members (1913), pp. 329–333

- ^ McDonald 1985, pp. 165–175.

- ^ McDonald 1985, p. 166-170.

- ^ Brennan, Cianan (17 January 2017). "Central Bank completes sale of its Dublin HQ for €67 million". TheJournal.ie. Archived from the original on 18 January 2017. Retrieved 11 January 2021.

- ^ McDonald 1985, p. 118.

- ^ FUSIO. "Montague Burton, 19-22 Dame Street, South Great George's Street, Dublin 2, DUBLIN". Buildings of Ireland. Retrieved 13 July 2022.

- ^ "Love letter to Gay Spar: Dublin's most beloved convenient store". LovinDublin.com. Retrieved 19 December 2022.

- ^ Hyland, Claire (29 June 2019). "'Gay Spar' Has Basically Won Pride By Coming Out For The Festival". Retrieved 19 December 2022.

- ^ "2022, the year Gay Spar officially came out". LovinDublin.com. Retrieved 19 December 2022.

- ^ Slabbekoorn, Zayda (28 June 2022). "Iconic Gay Spar comes out during Dublin Pride celebrations". GCN. Retrieved 19 December 2022.

- ^ Finlay, Fergus (23 September 2014). "Thomas Barnardo changed the way we think about children". Irish Examiner. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- ^ McDonald 1985, p. 318-319.

- ^ "'Occupy Dame Street' protest in Dublin". RTÉ News. Raidió Teilifís Éireann. 9 October 2011. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- ^ "Occupy Dame Street protest enters third night". RTÉ News. Raidió Teilifís Éireann. 10 October 2011. Retrieved 10 October 2011.

- ^ Nihill, Cían (5 November 2011). "'Occupy Dame Street' campaign prepared for long haul". The Irish Times. Irish Times Trust. Retrieved 5 November 2011.

Sources

- Casey, Christine (2005). Dublin: The City Within the Grand and Royal Canals and the Circular Road with the Phoenix Park. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-30010-923-8.

- McDonald, Frank (1985). The Destruction of Dublin. Gill and MacMillan. ISBN 0-7171-1386-8.

- Maxwell, Constantia (1997). Dublin Under the Georges. Lambay Books. ISBN 0-7089-4497-3.