Agrin

| Agrin NtA domain | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | NtA | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF03146 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR004850 | ||||||||

| SCOP2 | 1jc7 / SCOPe / SUPFAM | ||||||||

| |||||||||

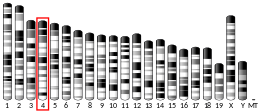

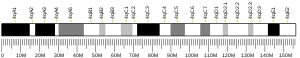

Agrin is a large proteoglycan whose best-characterised role is in the development of the neuromuscular junction during embryogenesis. Agrin is named based on its involvement in the aggregation of acetylcholine receptors during synaptogenesis. In humans, this protein is encoded by the AGRN gene.[5][6][7]

This protein has nine domains homologous to protease inhibitors.[8] It may also have functions in other tissues and during other stages of development. It is a major proteoglycan component in the glomerular basement membrane and may play a role in the renal filtration and cell-matrix interactions.[9]

Agrin functions by activating the MuSK protein (for Muscle-Specific Kinase), [10] which is a receptor tyrosine kinase required for the formation and maintenance of the neuromuscular junction.[11] Agrin is required to activate MuSK.[12] Agrin is also required for neuromuscular junction formation.[13]

Discovery

Agrin was first identified by the U.J. McMahan laboratory, Stanford University.[14]

Mechanism of action

During development in humans, the growing end of motor neuron axons secrete a protein called agrin.[15] When secreted, agrin binds to several receptors on the surface of skeletal muscle. The receptor which appears to be required for the formation of the neuromuscular junction (NMJ) is called the MuSK receptor (Muscle specific kinase).[16][17] MuSK is a receptor tyrosine kinase - meaning that it induces cellular signaling by causing the addition of phosphate molecules to particular tyrosines on itself and on proteins that bind the cytoplasmic domain of the receptor.

In addition to MuSK, agrin binds several other proteins on the surface of muscle, including dystroglycan and laminin. It is seen that these additional binding steps are required to stabilize the NMJ.

The requirement for Agrin and MuSK in the formation of the NMJ was demonstrated primarily by knockout mouse studies. In mice that are deficient for either protein, the neuromuscular junction does not form.[18] Many other proteins also comprise the NMJ, and are required to maintain its integrity. For example, MuSK also binds a protein called "dishevelled" (Dvl), which is in the Wnt signalling pathway. Dvl is additionally required for MuSK-mediated clustering of AChRs, since inhibition of Dvl blocks clustering.

Signaling

The nerve secretes agrin, resulting in phosphorylation of the MuSK receptor.

It seems that the MuSK receptor recruits casein kinase 2, which is required for clustering.[19]

A protein called rapsyn is then recruited to the primary MuSK scaffold, to induce the additional clustering of acetylcholine receptors (AChR). This is thought of as the secondary scaffold. A protein called Dok-7 has shown to be additionally required for the formation of the secondary scaffold; it is apparently recruited after MuSK phosphorylation and before acetylcholine receptors are clustered.

Structure

There are three potential heparan sulfate (HS) attachment sites within the primary structure of agrin, but it is thought that only two of these actually carry HS chains when the protein is expressed.

In fact, one study concluded that at least two attachment sites are necessary by inducing synthetic agents. Since agrin fragments induce acetylcholine receptor aggregation as well as phosphorylation of the MuSK receptor, researchers spliced them and found that the variant did not trigger phosphorylation. It has also been shown that the G3 domain of agrin is very plastic, meaning it can discriminate between binding partners for a better fit.[20]

Heparan sulfate glycosaminoglycans covalently linked to the agrin protein have been shown to play a role in the clustering of AChR. Interference in the correct formation of heparan sulfate through the addition of chlorate to skeletal muscle cell culture results in a decrease in the frequency of spontaneous acetylcholine receptor (AChR) clustering. It may be that rather than solely binding directly to the agrin protein core a number of components of the secondary scaffold may also interact with its heparan sulfate side-chains.[21]

A role in the retention of anionic macromolecules within the vasculature has also been suggested for agrin-linked HS at the glomerular or alveolar basement membrane.

Functions

Agrin may play an important role in the basement membrane of the microvasculature as well as in synaptic plasticity. Also, agrin may be involved in blood–brain barrier (BBB) formation and/or function [22][23] and it influences Aβ homeostasis.[24]

Research

Agrin is investigated in relation with osteoarthritis.[25][26] In addition, by its ability to activate the Hippo signaling pathway, agrin is emerging as a key proteoglycan in the tumor microenvironment.[27]

Clinical significance

AGRN gene mutation leads to congenital myasthenic syndromes[28][29][30] and myasthenia gravis.[31][32]

A recent genome-wide association study (GWAS) has found that genetic variations in AGRN are associated with late-onset sporadic Alzheimer’s disease (LOAD). These genetic variations alter β-amyloid homeostasis contributing to its accumulation and plaque formation.[33][34]

References

- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000188157 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000041936 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Rupp F, Payan DG, Magill-Solc C, Cowan DM, Scheller RH (May 1991). "Structure and expression of a rat agrin". Neuron. 6 (5): 811–823. doi:10.1016/0896-6273(91)90177-2. PMID 1851019. S2CID 44440186.

- ^ Kröger S, Schröder JE (October 2002). "Agrin in the developing CNS: new roles for a synapse organizer". News in Physiological Sciences. 17 (5): 207–212. doi:10.1152/nips.01390.2002. PMID 12270958. S2CID 2988918.

- ^ Groffen AJ, Buskens CA, van Kuppevelt TH, Veerkamp JH, Monnens LA, van den Heuvel LP (May 1998). "Primary structure and high expression of human agrin in basement membranes of adult lung and kidney". European Journal of Biochemistry. 254 (1): 123–128. doi:10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2540123.x. PMID 9652404.

- ^ Tsen G, Halfter W, Kröger S, Cole GJ (February 1995). "Agrin is a heparan sulfate proteoglycan". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 270 (7): 3392–3399. doi:10.1074/jbc.270.7.3392. PMID 7852425.

- ^ Groffen AJ, Ruegg MA, Dijkman H, van de Velden TJ, Buskens CA, van den Born J, et al. (January 1998). "Agrin is a major heparan sulfate proteoglycan in the human glomerular basement membrane". The Journal of Histochemistry and Cytochemistry. 46 (1): 19–27. doi:10.1177/002215549804600104. PMID 9405491.

- ^ Valenzuela DM, Stitt TN, DiStefano PS, Rojas E, Mattsson K, Compton DL, Nunez L, Park JS, Stark JL, Gies DR, Thomas S, LeBeau MM, Fernald AA, Copeland NG, Jenkins NA, Burden SJ, Glass DJ, Yancopoulos GD (Sep 1995). "Receptor tyrosine kinase specific for the skeletal muscle lineage: expression in embryonic muscle, at the neuromuscular junction, and after injury". Neuron. 15 (3): 573–584. doi:10.1016/0896-6273(95)90146-9. PMID 7546737.

- ^ DeChiara TM, Bowen DC, Valenzuela DM, Simmons MV, Poueymirou WT, Thomas S, Kinetz E, Compton DL, Rojas E, Park JS, Smith C, DiStefano PS, Glass DJ, Burden SJ, Yancopoulos GD (May 1996). "The receptor tyrosine kinase MuSK is required for neuromuscular junction formation in vivo". Cell. 85 (4): 501–512. doi:10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81251-9. PMID 8653786.

- ^ Glass DJ, Bowen DC, Stitt TN, Radziejewski C, Bruno J, Ryan TE, Gies DR, Shah S, Mattson K, Burden SJ, DiStefano PS, Valenzuela DM, DeChiara TM, Yancopoulos GD (May 1996). "Agrin acts via a MuSK receptor complex". Cell. 85 (4): 513–523. doi:10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81252-0. PMID 8653787.

- ^ Gautam M, Noakes PG, Moscoso L, Rupp F, Scheller RH, Merlie JP, Sanes JR (May 1996). "Defective neuromuscular synaptogenesis in agrin-deficient mutant mice". Cell. 85 (4): 525–535. doi:10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81253-2. PMID 8653788.

- ^ Magill C, Reist NE, Fallon JR, Nitkin RM, Wallace BG, McMahan UJ (1987). Agrin. Progress in Brain Research. Vol. 71. pp. 391–396. doi:10.1016/S0079-6123(08)61840-3. ISBN 978-0-444-80814-1. PMID 3035610.

- ^ Sanes JR, Lichtman JW (November 2001). "Induction, assembly, maturation and maintenance of a postsynaptic apparatus". Nature Reviews. Neuroscience. 2 (11): 791–805. doi:10.1038/35097557. PMID 11715056. S2CID 52802445.

- ^ Glass DJ, Bowen DC, Stitt TN, Radziejewski C, Bruno J, Ryan TE, et al. (May 1996). "Agrin acts via a MuSK receptor complex". Cell. 85 (4): 513–523. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81252-0. PMID 8653787. S2CID 14930468.

- ^ Sanes JR, Apel ED, Gautam M, Glass D, Grady RM, Martin PT, et al. (May 1998). "Agrin receptors at the skeletal neuromuscular junction". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 841 (1): 1–13. Bibcode:1998NYASA.841....1S. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb10905.x. PMID 9668217. S2CID 20097480.

- ^ Gautam M, Noakes PG, Moscoso L, Rupp F, Scheller RH, Merlie JP, Sanes JR (May 1996). "Defective neuromuscular synaptogenesis in agrin-deficient mutant mice". Cell. 85 (4): 525–535. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81253-2. PMID 8653788. S2CID 12517490.

- ^ Cheusova T, Khan MA, Schubert SW, Gavin AC, Buchou T, Jacob G, et al. (July 2006). "Casein kinase 2-dependent serine phosphorylation of MuSK regulates acetylcholine receptor aggregation at the neuromuscular junction". Genes & Development. 20 (13): 1800–1816. doi:10.1101/gad.375206. PMC 1522076. PMID 16818610.

- ^ PDB: 1PZ7; Stetefeld J, Alexandrescu AT, Maciejewski MW, Jenny M, Rathgeb-Szabo K, Schulthess T, et al. (March 2004). "Modulation of agrin function by alternative splicing and Ca2+ binding". Structure. 12 (3): 503–515. doi:10.1016/j.str.2004.02.001. PMID 15016366.

- ^ McDonnell KM, Grow WA (2004). "Reduced glycosaminoglycan sulfation diminishes the agrin signal transduction pathway". Developmental Neuroscience. 26 (1): 1–10. doi:10.1159/000080706. PMID 15509893. S2CID 42558266.

- ^ Donahue JE, Berzin TM, Rafii MS, Glass DJ, Yancopoulos GD, Fallon JR, Stopa EG (May 1999). "Agrin in Alzheimer's disease: altered solubility and abnormal distribution within microvasculature and brain parenchyma". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 96 (11): 6468–6472. Bibcode:1999PNAS...96.6468D. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.11.6468. PMC 26905. PMID 10339611.

- ^ Wolburg H, Noell S, Wolburg-Buchholz K, Mack A, Fallier-Becker P (April 2009). "Agrin, aquaporin-4, and astrocyte polarity as an important feature of the blood-brain barrier". The Neuroscientist. 15 (2): 180–193. doi:10.1177/1073858408329509. PMID 19307424. S2CID 25922007.

- ^ Rauch SM, Huen K, Miller MC, Chaudry H, Lau M, Sanes JR, et al. (December 2011). "Changes in brain β-amyloid deposition and aquaporin 4 levels in response to altered agrin expression in mice". Journal of Neuropathology and Experimental Neurology. 70 (12): 1124–1137. doi:10.1097/NEN.0b013e31823b0b12. PMC 3223604. PMID 22082664.

- ^ Thorup AS, Dell'Accio F, Eldridge SE (16 September 2020). "Regrowing knee cartilage: new animal studies show promise". The Conversation. Retrieved 2020-10-12.

- ^ Eldridge SE, Barawi A, Wang H, Roelofs AJ, Kaneva M, Guan Z, et al. (September 2020). "Agrin induces long-term osteochondral regeneration by supporting repair morphogenesis". Science Translational Medicine. 12 (559): eaax9086. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.aax9086. hdl:2164/15360. PMID 32878982. S2CID 221469142.

- ^ Chakraborty S, Hong W (February 2018). "Linking Extracellular Matrix Agrin to the Hippo Pathway in Liver Cancer and Beyond". Cancers. 10 (2): 45. doi:10.3390/cancers10020045. PMC 5836077. PMID 29415512.

- ^ Gan S, Yang H, Xiao T, Pan Z, Wu L (October 2020). "AGRN Gene Mutation Leads to Congenital Myasthenia Syndromes: A Pediatric Case Report and Literature Review". Neuropediatrics. 51 (5): 364–367. doi:10.1055/s-0040-1708534. PMID 32221959. S2CID 214694892.

- ^ Ohkawara B, Shen X, Selcen D, Nazim M, Bril V, Tarnopolsky MA, et al. (April 2020). "Congenital myasthenic syndrome-associated agrin variants affect clustering of acetylcholine receptors in a domain-specific manner". JCI Insight. 5 (7): 132023. doi:10.1172/jci.insight.132023. PMC 7205260. PMID 32271162.

- ^ Xi J, Yan C, Liu WW, Qiao K, Lin J, Tian X, et al. (December 2017). "Novel SEA and LG2 Agrin mutations causing congenital Myasthenic syndrome". Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases. 12 (1): 182. doi:10.1186/s13023-017-0732-z. PMC 5735900. PMID 29258548.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Zhang B, Shen C, Bealmear B, Ragheb S, Xiong WC, Lewis RA, et al. (2014-03-14). "Autoantibodies to agrin in myasthenia gravis patients". PLOS ONE. 9 (3): e91816. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...991816Z. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0091816. PMC 3954737. PMID 24632822.

- ^ Yan M, Xing GL, Xiong WC, Mei L (February 2018). "Agrin and LRP4 antibodies as new biomarkers of myasthenia gravis". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1413 (1): 126–135. Bibcode:2018NYASA1413..126Y. doi:10.1111/nyas.13573. PMID 29377176. S2CID 46757850.

- ^ Wightman DP, Jansen IE, Savage JE, Shadrin AA, Bahrami S, Holland D, et al. (September 2021). "A genome-wide association study with 1,126,563 individuals identifies new risk loci for Alzheimer's disease". Nature Genetics. 53 (9): 1276–1282. doi:10.1038/s41588-021-00921-z. hdl:1871.1/61f01aa9-6dc7-4213-be2a-d3fe622db488. PMC 10243600. PMID 34493870. S2CID 237442349.

- ^ Rahman MM, Lendel C (August 2021). "Extracellular protein components of amyloid plaques and their roles in Alzheimer's disease pathology". Molecular Neurodegeneration. 16 (1): 59. doi:10.1186/s13024-021-00465-0. PMC 8400902. PMID 34454574.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link)

Further reading

- Gros K, Matkovič U, Parato G, Miš K, Luin E, Bernareggi A, et al. (October 2022). "Neuronal Agrin Promotes Proliferation of Primary Human Myoblasts in an Age-Dependent Manner". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 23 (19): 11784. doi:10.3390/ijms231911784. PMC 9570459. PMID 36233091.

- Kesari S, Lasner TM, Balsara KR, Randazzo BP, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ, Fraser NW (March 1998). "A neuroattenuated ICP34.5-deficient herpes simplex virus type 1 replicates in ependymal cells of the murine central nervous system". The Journal of General Virology. 79 ( Pt 3) (3): 525–36. doi:10.1099/0022-1317-79-3-525. PMID 9519831.

- dde Souza Ramos JT, Ferrari FS, Andrade MF, de Melo CS, Boas PJ, Costa NA, et al. (February 2022). "Association between frailty and C-terminal agrin fragment with 3-month mortality following ST-elevation myocardial infarction". Experimental Gerontology. 158: 111658. doi:10.1016/j.exger.2021.111658. PMID 34920013. S2CID 245149341.

- Zieliński AE (1996). "Specific immunotherapy in pollinosis: I. Valuation of certain cytoimmunological indicators over the course of four years of immunotherapy in pollinosis". Journal of Investigational Allergology & Clinical Immunology. 6 (5): 307–14. PMID 8959542.

External links

- Human AGRN genome location and AGRN gene details page in the UCSC Genome Browser.