Serse

Serse (Italian pronunciation: [ˈsɛrse]; English title: Xerxes; HWV 40) is an opera seria in three acts by George Frideric Handel. It was first performed in London on 15 April 1738. The Italian libretto was adapted by an unknown hand from that by Silvio Stampiglia (1664–1725) for an earlier opera of the same name by Giovanni Bononcini in 1694. Stampiglia's libretto was itself based on one by Nicolò Minato (ca.1627–1698) that was set by Francesco Cavalli in 1654. The opera is set in Persia (modern-day Iran) about 470 BC and is very loosely based upon Xerxes I of Persia. Serse, originally sung by a mezzo-soprano castrato, is now usually performed by a female mezzo-soprano or countertenor.

The opening aria, "Ombra mai fu", sung by Xerxes to a plane tree (Platanus orientalis), is set to one of Handel's best-known melodies, and is often known as Handel's "Largo" (despite being marked "larghetto" in the score).

Composition history

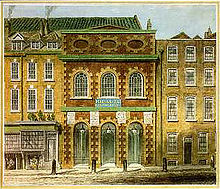

In late 1737 the King's Theatre, London, commissioned Handel to write two new operas. The first, Faramondo, was premiered on 3 January 1738. By this time, Handel had already begun work on Serse. The first act was composed between 26 December 1737 and 9 January 1738, the second was ready by 25 January, the third by 6 February, and Handel put the finishing touches to the score on 14 February. Serse was first performed at the King's Theatre, Haymarket on 15 April 1738.[1]

The first production was a complete failure.[2] The audience may have been confused by the innovative nature of the work. Unlike his other operas for London, Handel included comic (buffo) elements in Serse. Although this had been typical for 17th-century Venetian works such as Cavalli's original setting of the libretto, by the 1730s an opera seria was expected to be wholly serious, with no mixing of the genres of tragedy and comedy or high and low class characters. The musicologist Charles Burney later took Serse to task for violating decorum in this way, writing: "I have not been able to discover the author of the words of this drama: but it is one of the worst Handel ever set to Music: for besides feeble writing, there is a mixture of tragic-comedy and buffoonery in it, which Apostolo Zeno and Metastasio had banished from serious opera."[3] Another unusual aspect of Serse is the number of short, one-part arias, when a typical opera seria of Handel's time was almost wholly made up of long, three-part da capo arias. This feature particularly struck the Earl of Shaftesbury, who attended the premiere and admired the opera. He noted "the airs too, for brevity's sake, as the opera would otherwise be too long [,] fall without any recitativ' intervening from one into another[,] that tis difficult to understand till it comes by frequent hearing to be well known. My own judgment is that it is a capital opera notwithstanding tis called a ballad one."[3] It is likely that Handel had been influenced, both as regards the comedy and the absence of da capo arias, by the success in London of ballad operas such as The Beggar's Opera and John Frederick Lampe's The Dragon of Wantley, the latter of which was visited by Handel.[4]

Performance history

Serse disappeared from the stage for almost two hundred years. It enjoyed its first modern revival in Göttingen on 5 July 1924 in a version by Oskar Hagen. By 1926 this version had been staged at least 90 times in 15 German cities. Serse's success has continued.[5] According to Winton Dean, Serse is Handel's most popular opera with modern audiences after Giulio Cesare.[6] The very features which 18th-century listeners found so disconcerting – the shortness of the arias and the admixture of comedy – may account for its appeal to the 20th and the 21st centuries.[7]

Serse was produced for the stage at the La Scala Theater in Milan, Italy in January 1962. The production was conducted by Piero Bellugi, and an all-star cast featuring Mirella Freni, Rolando Panerai, Fiorenza Cossotto, Irene Companez, Leonardo Monreale, Franco Calabrese, and Luigi Alva in the title role. Because Handel operas were still in a relatively early stage of their return to the stage, musicians had not yet thought to ornament the da capo sections (repetition of the A section) of the arias and thus, they were not ornamented. A complete recording was made in 1979. A particularly highly acclaimed production, sung in English, was staged by the English National Opera in 1985, to mark the 300th anniversary of the composer's birth. Conducted by Sir Charles Mackerras, it was directed by Nicholas Hytner, who also translated the libretto, and starred Ann Murray in the title role, with Valerie Masterson as Romilda, Christopher Robson as Arsamene, and Lesley Garrett as Atalanta.[8] The production returned for a sixth revival to the London Coliseum in September 2014, starring Alice Coote as Xerxes.[9] Hytner's production was also performed by San Francisco Opera in 2011.[10] Numerous performances around the world include the Royal Opera of Versailles in 2017,[11] Opernhaus Düsseldorf in 2019 and the Detroit Opera in 2023.[12]

Roles

| Role | Voice type | Premiere cast, 15 April 1738[13] |

|---|---|---|

| Serse (Xerxes), King of Persia | soprano castrato | Gaetano Majorano ("Caffarelli") |

| Arsamene, brother of Serse, in love with Romilda | contralto | Maria Antonia Marchesini ("La Lucchesina") |

| Amastre, princess of a neighbouring kingdom, betrothed to Serse but jilted by him | contralto | Antonia Merighi |

| Romilda, daughter of Ariodate, in love with Arsamene | soprano | Élisabeth Duparc ("La Francesina") |

| Atalanta, Romilda's sister, also in love with Arsamene | soprano | Margherita Chimenti ("La Droghierina") |

| Ariodate, a prince under Serse's command,father of Romilda and Atalanta | bass | Antonio Montagnana |

| Elviro, Arsamene's servant | baritone | Antonio Lottini |

Synopsis

Act 1

A garden with a large plane tree and a summerhouse on the side

The King of Persia, Serse, gives effusive, loving thanks to the plane tree for furnishing him with shade (Arioso: "Ombra mai fu"). His brother Arsamene, with his buffoonish servant Elviro, enters, looking for Arsamene's sweetheart Romilda. They stop as they hear her singing from the summerhouse. Romilda is making gentle fun of Serse with her song. He is in love with a tree, but the tree does not return his affection. Serse does not know that his brother is in love with the singer, and entranced by her music, Serse announces that he wants her to be his. Arsamene is horrified when Serse orders him to tell Romilda of his love. Arsamene warns Romilda of what Serse wants — this encourages Atalanta, Romilda's sister, who is secretly in love with Arsamene also and hopes that Romilda will be Serse's and then she can have Arsamene.

Serse tells Romilda that he wants her for his queen and when Arsamene remonstrates Serse banishes him. Romilda is determined to remain faithful to the man she loves, Arsamene.

Outside the palace

Princess Amastre now arrives, disguised as a man. She was engaged to Serse but he jilted her and she is furiously determined to be revenged.

Ariodate, general to Serse and father of Romilda and Atalanta, enters with news of a great military victory he has won. Serse is grateful to him and promises that as a reward his daughter Romilda will marry a man equal in rank to the King himself.

Arsamene gives Elviro a letter for Romilda, telling her how distressed he is at their forced separation and pledging to try to visit her in secret. Romilda's sister Atalanta, hoping to secure Arsamene for herself, tells Romilda that Arsamene is in love with another girl, but Romilda does not believe it.

Act 2

A square in the city

Elviro has disguised himself as a flower-seller in order to deliver his master Arsamene's letter to Romilda, and is also putting on a rural accent. He does not approve of the King's desire to marry a mere subject such as Romilda and makes this clear. Princess Amastre, in her disguise as a man, hears Elviro expressing this and she is aghast at the King's plan to marry another when he promised to be hers (Aria: "Or che siete speranze tradite").

Amastre leaves in despair and rage and Atalanta enters. Elviro tells her he has a letter for her sister and Atalanta takes it, promising to give it to Romilda. Instead she mischievously shows the letter to the King, telling him that Arsamene sent it to her and no longer loves Romilda. Serse takes the letter and shows it to Romilda, telling her Arsamene is now in love with Atalanta, not her. Romilda is shaken (Aria: "È gelosia").

Princess Amastre has decided to kill herself but Elviro arrives in time to stop her. She resolves to confront the King with his ill-treatment of her. Elviro tells Amastre that Romilda now loves Serse: Amastre is devastated (Aria: "Anima infida").

By the newly-constructed bridge spanning the Hellespont and thus uniting Asia and Europe

Sailors hail the completion of the bridge, constructed under Serse's orders, and Serse orders his general Ariodate to cross the bridge with his army and invade Europe.

Serse encounters his heart-broken brother Arsamene and tells him to cheer up, he can marry the woman he now loves, Atalanta, no problem. Arsamene is confused and insists he loves Romilda, not Atalanta. Hearing this, the King advises Atalanta to forget about Arsamene, but she says that is impossible.

Elviro watches as a violent storm threatens to destroy the new bridge. He calms his nerves with drink.

Outside the city in a garden

Serse and Arsamene are both suffering from jealousy and the tribulations of the love lorn. Serse again implores Romilda to marry him but she remains firm in her refusal. The violently furious Amastre appears and draws a sword on the King but Romilda intervenes. Amastre says Romilda should not be forced to marry a man she does not love, and Romilda praises those who are true to their hearts (Aria: "Chi cede al furore").

Act 3

A gallery

Romilda and Arsamene are having a lovers' spat about that letter, but calm down when Atalanta appears and admits her deception. She has decided she will have to find another boyfriend somewhere else.

Serse again implores Romilda to marry him and she tells him to seek her father's permission, if he consents, she will. Arsamenes bitterly reproaches her for this (Aria: "Amor, tiranno Amor").

Serse once more asks Ariodate if he is happy for his daughter Romilda to marry someone equal in rank to the King. Ariodate thinks Serse means Arsamene and happily gives his consent. Serse tells Romilda that her father has agreed to their marriage but Romilda, trying to put him off, tells him that Arsamene loves her and in fact he has kissed her. Serse, furious, orders his brother to be put to death.

Amastre asks Romilda to take a letter to the King, telling her that this will help her. Amastre bewails her plight, having been abandoned by Serse, who promised to be hers (Aria: "Cagion son io").

Arsamene blames Romilda for the fact that he has been sentenced to death, and the lovers again quarrel (Duet: "Troppo oltraggi la mia fede").

The temple of the sun

Arsamene and Romilda have been summoned to the temple and they come in, still quarreling, but they are amazed and overjoyed when Ariodate tells them that Serse has agreed to their wedding and he marries them then and there.

Serse enters, ready to marry Romilda, and is enraged when he discovers that it is too late, Ariodate has married his daughter to Arsamene. Serse bitterly denounces Ariodate for that and is even more enraged when a letter arrives, apparently from Romilda, accusing him of faithlessness. When he discovers that the letter is actually from his previous fiance Amastre, whom he jilted, his fury only increases (Aria: "Crude furie degl' orridi abissi").

Serse takes his sword and orders Arsamene to kill Romilda with it; but Amastre interrupts this and asks Serse if he truly wants treachery and infidelity to be punished. Serse says he does whereupon Amastre reveals her true identity as Serse's betrothed. Serse, abashed, admits his fault – he will marry Amastre as he promised, he wishes his brother Arsamene and Romilda happiness in their marriage, and all celebrate the fortunate outcome of events (Chorus: "Ritorna a noi la calma").[13][14]

Historical motives

The libretto includes some motives that are based upon events that actually happened. Serse, Amastre and Arsamene are all based on historical persons. The story of Xerxes wanting to marry the love of his brother Arsamenes is based upon a real story. In reality though, it was a wife of another brother Xerxes fell in love with but failed to marry himself.[15] The collapsing of a bridge over the Hellespont and Xerxes returning from a catastrophic campaign in Greece are real events during the reign of Xerxes, though they are anachronistic here.

Recordings

Audio recordings

Video recording

| Year | Cast: Serse, Romilda, Arsamene, Amastre, Atalanta, Elviro, Ariodate |

Conductor, orchestra |

Stage director | Label |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | Gaëlle Arquez, Elizabeth Sutphen, Lawrence Zazzo, Tanja Ariane Baumgartner, Louise Alder, Thomas Faulkner, Brandon Cedel |

Constantinos Carydis Frankfurter Opern- und Museumsorchester |

Tilmann Köhler | Blu-ray: C Major Cat: 748004 |

References

Notes

- ^ Best, p. 14.

- ^ Dean 1995, p. 135.

- ^ a b Best, p. 15

- ^ Keates 2014, p. 10.

- ^ Dean 1995, p. 166, calls Hagen's vocal score of Serse "a grinning parody".

- ^ Opera and the Enlightenment p. 135

- ^ Best, p. 18.

- ^ Evan Dickerson, "Seen and Heard Opera Review" on Seen and Heard International website, retrieved 2 October 2014

- ^ William Hartston, "Handel's Xerxes by the English National Opera: Astonishing comedy, glorious fun", Daily Express (London), 17 September 2014. Accessed 2 October 2014.

- ^ Rowe, Georgia. "Serse". www.operanews.com. Retrieved 4 January 2020.

- ^ Servidei, Laura. "Baroque pyrotechnics: Handel's Serse dazzles at Versailles". bachtrack.com. Retrieved 3 January 2020.

- ^ Rye, Matthew. "All the world's a stage: Xerxes as a comedy of backstage rivalry". bachtrack.com. Retrieved 3 January 2020.

- ^ a b "Serse". Handel & Hendrix in London. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- ^ Hicks, Anthony (2001). "Serse (Xerxes)". In Sadie, Stanley; Tyrrell, John (eds.). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan Publishers. ISBN 978-1-56159-239-5.

- ^ Herodotus, Histories: IX, 108–110

- ^ "Classical recordings – Search: serse handel (page 1 of 44)". Presto Classical.

Sources

- Best, Terence. Booklet notes to the recording by William Christie

- Dean, Winton (1995). "Handel's Serse". In Thomas Bauman (ed.). Opera and the Enlightenment. Cambridge University Press.

- Keates, Jonathan (2014). "Musical London 1737–38", in Xerxes, (programme of the English National Opera production revial). pp. 10–13.

Further reading

- Dean, Winton (2006), Handel's Operas, 1726–1741, Boydell Press, ISBN 1843832682 The second of the two-volume definitive reference on the operas of Handel.

External links

- Serse: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project