Vale Royal Abbey

| Monastery information | |

|---|---|

| Full name | The abbey church of St Mary the Virgin, St Nicholas, and St Nicasius, Vale Royal |

| Other names | Vale Royal Abbey |

| Order | Cistercian |

| Established | 1270/1277 |

| Disestablished | 1538 |

| Mother house | Dore Abbey |

| Dedicated to | Virgin Mary, St Nicholas, St Nicasius |

| Diocese | Diocese of Lichfield |

| Controlled churches | Frodsham, Weaverham, Ashbourne, Castleton, St Padarn's Church, Llanbadarn Fawr |

| People | |

| Founder(s) | Edward I |

| Important associated figures | Edward I, Thomas Holcroft |

| Site | |

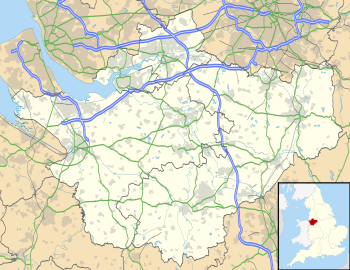

| Location | Whitegate, Cheshire, United Kingdom |

| Coordinates | 53°13′29″N 2°32′33″W / 53.2247°N 2.5426°W |

| Visible remains | Foundations of the church, surviving rooms within later house, earthworks. Gate chapel survives as parish church |

| Public access | None |

Vale Royal Abbey is a former medieval abbey and later country house in Whitegate, England. The precise location and boundaries of the abbey are difficult to determine in today's landscape. The original building was founded c. 1270 by the Lord Edward, later Edward I, for Cistercian monks. Edward had supposedly taken a vow during a rough sea crossing in the 1260s. Civil wars and political upheaval delayed the build until 1272, the year he inherited the throne. The original site at Darnhall was unsatisfactory, so was moved a few miles north to the Delamere Forest. Edward intended the structure to be on a grand scale—had it been completed it would have been the largest Cistercian monastery in the country—but his ambitions were frustrated by recurring financial difficulties.

Early during construction, England became involved in war with Wales. As the treasury was thus in need of resources, Vale Royal lost all of its grants, skilled masons and builders. When work resumed in the late 13th century, the building was considerably smaller than originally planned. The project encountered other problems. The abbey was mismanaged and poor relations with the local population sparked outbreaks of violence on a number of occasions. In one such episode in 1336, the abbot was killed by a mob. Internal discipline was also frequently bad; in the 14th century the monks were often accused of serious crimes including rape, and the abbots were seen as protecting them. The abbey was devastated at least twice: in the early 1300s a fire destroyed the entire monastic grange, and in 1359—soon after building work had recommenced under the patronage of Edward the Black Prince—a great storm caused the collapse of the massive nave.

Vale Royal was closed in 1538 by Henry VIII during his dissolution of the Monasteries campaign, although not without controversy. In the course of the proceedings, the abbot was accused of treason and murder, and he in turn accused the King's men of fraudulently forging the abbot's signature on essential legal documents but the abbey's closure was inevitable, and its estates were sold to a member of the local Cheshire gentry, Thomas Holcroft. Holcroft pulled much of it down (including the church), although he incorporated some of the cloister buildings into the new mansion he built on the site in the 1540s. This was subsequently considerably altered and extended by successive generations of Holcrofts. Vale Royal came into the possession of the Cholmondeley family during the early 1600s, and remained the family seat for more than 300 years.

The Cholmondeley family remodelled the exterior during the 18th century, and Thomas Cholmondeley carried out extensive work in the early 1800s. Substantial alterations were carried out under the auspices of Edward Blore in 1833 and by John Douglas from 1860.[1] Sold soon after the Second World War, it was turned into a private golf club. The building remains habitable and contains parts of the medieval abbey, including its refectory and kitchen. The foundations of the church and cloister have been excavated; Vale Royal Abbey, a scheduled monument, is listed in the National Heritage List for England as a Grade II* listed building.

Foundation

Vale Royal Abbey was originally founded in Darnhall by the Lord Edward, the future Edward I, before his accession to the throne. He was supposedly caught in rough weather crossing the English Channel in the early 1260s, during which, the abbey's own chronicler[note 1] later wrote, the King's son and his entourage feared for their lives. Edward pleaded with the Virgin Mary to intercede, and vowed to found an abbey in her name if they were saved. According to the chronicle, the sea calmed almost immediately and the ships returned safely to England. When the last man had stepped ashore, the chronicler continues, the storm resumed more violently than ever and Edward's ship was destroyed in the harbour.[note 2]

This chronology, however, does not fit with what is known of Edward's movements in this period. His only crusade was in 1270, after which he did not return until his father Henry III had died in 1272. By that time, Darnhall Abbey's foundation charter had already been granted. The charter mentions the King being "sometime in danger upon the sea",[2] and it has been suggested by a recent biographer that it refers to a stormy English Channel crossing during the 1260s.[3][4][note 3] Michael Prestwich has noted a crusader connection for Edward's new foundation: the first charter concerned with the project is dated four years earlier than the foundation charter, in August 1270, just before Edward left on crusade. Prestwich suggests that Edward probably founded the abbey more as a plea for Mary's future protection during his crusade rather than her past intervention at sea.[4]

Regardless of Edward's intentions when founding the abbey, the deteriorating political situation and eventual civil war between his father and the nobility —in which Edward played a prominent role— stalled plans for the abbey's build. In 1265 the rebel barons were defeated at the Battle of Evesham, and the following year negotiations were completed for the establishment of a Cistercian monastery in Darnhall in Cheshire.[6] This was to be paid for with the manor house and estate of the earls of Chester, which were now in royal hands.[7] In August 1270, Edward granted another charter at Winchester[8] to his new abbey with a further endowment of land and churches.[9]

Closure of Darnhall Abbey

The abbey's build was problematic. Preparation took considerable time, and the first monks—led by Abbot John Chaumpeneys[6]—did not arrive at Darnhall from Dore Abbey (Vale Royal's motherhouse)[10] until 1274.[9] The new abbey provoked anger and resistance from local people, who believed that it (and its newly granted lands) threatened their livelihoods.[11] The abbey had received the forestry rights and free warren of Darnhall Forest, which surrounded the villages, and in which the villagers had previously had free rein.[6]

Darnhall's location was unsuitable for a large construction.[6][9][note 4] It may have been intended as a temporary site;[12] in 1276 Edward (by then King) agreed to move the abbey to a more suitable location. A new site was chosen in nearby Over, on the edge of the Forest of Mondrem. On 13 August 1277, the king and Queen Eleanor, their son Alphonso and a number of nobles arrived at Over to lay the foundation stones of the new abbey[6] for the high altar.[7] Chaumpeneys then said a celebratory mass.[13] In 1281, the monks moved from Darnhall to temporary accommodations on the Vale Royal site while the abbey was being built. Pevsner's Buildings of England described Vale Royal as a "late foundation as Cistercian settlements go".[14] It was intended to be the largest and most elaborate Cistercian church in Christian Europe.[15]

The precise location and boundaries of the site is difficult to determine. It lay broadly within the monks' manor of Conersley, on parcels of land later renamed Vale Royal after the royal patron. The southern boundary was probably around Petty Pool, past Earnslow to the River Weaver. Its total area was about 400 acres (160 ha).[12]

Construction

Building

During an excavation in 1958, the site of the abbey—at the time, heavily wooded and similar to its medieval appearance—was described as:

On the left bank of the river Weaver, 2½ miles southwest of Northwich. It stands on level ground from which there is a fairly rapid slope northwards down to the river, a factor which must have assisted considerably in the natural drainage of the heavy clay subsoil.[16]

— F. H. Thompson, Excavations at the Cistercian Abbey of Vale Royal, Cheshire, 1958

Edward had grand ambitions for Vale Royal, as an important abbey, surpassing all the other houses of its order in Britain in scale and beauty. It was further intended to be symbolic of the wealth and power of the English monarchy and his own piety and greatness.[9] He intended the abbey to be more grandiose than his grandfather King John's abbey at Beaulieu,[17] and as a project, it was comparable to his father's Westminster Abbey. Henry, for example, had planned to be buried at Westminster, and Edward may have had similar plans for himself at Vale Royal.[18] Vale Royal Abbey was his largest—although only known—major act of piety; he did not fund any other houses.[19] The building's plans reflect Edward's enthusiasm. Fifty-one[20] masons were employed from around the country; they were rarely local men, and may have been pressed into service.[21] The chief architect, Walter of Hereford (one of the foremost of his day),[9][note 5] began work on a huge, elaborate High Gothic church the size of a cathedral.[27]

Plans were extremely detailed; the abbey was to be furnished with thirty copes, two silver crosses, six chalices, a gold collar, a silver pastoral staff and other valuable possessions.[28] It was to be 116 metres (381 ft) long and cruciform in shape, with a central tower.[27] The east end was semi-circular, with a chevet of 13 radiating chapels, some of which were square, and some polygonal.[27] Each of the transepts had—as was common with Cistercian churches[1]—a row of three chapels on its eastern side.[27] South of the church stood a cloister 42 metres (138 ft) square, surrounded by the domestic buildings.[27] The undermaster of the works from 1278 to 1280[29]—and paid three shillings a week[21]—was John of Battle, who would later build the King's memorial crosses after Eleanor's death.[30][31] Although Walter of Hereford initially seems to have found difficulty in gathering skilled masons to the project, in the second and third years recruitment was much improved.[32][note 6] At the same time, however, the number of masons employed decreased from 92 in 1277 to 53 by 1280, who were paid between £200 and £260 over the three years.[21][note 7]

According to contemporary accounts for 1277 to 1281, 35,000 cartloads of stone—over 30 per day—were brought over rough roads nine miles from the Eddisbury quarries,[37] five miles to the west.[38][note 8] Timber came from local forests—particularly Delamere[7] and Mondrem[38]—to build workshops and dwellings,[7][note 9] which together cost 45 shillings.[20] A total of £3,000 was spent on construction during these four years,[40] and in 1283 it was arranged that £1,000 per annum would be set aside for the ongoing building.[41] Funds were to be taken straight from the King's wardrobe.[42][note 10] The King put one of his personal clerks—one Leonius, son of Leonius—in charge of the financial administration, appointing him Chamberlain of the city of Chester and custodian of the King's works at Vale Royal.[21] Putting one man in charge of both posts was intended to accelerate the speed at which the abbey received its money, as until then, the local Exchequer received money which then had to be dispersed to the work's administrator.[23] Leonius held this post for the next three years, with the "full cooperation"[21] of the local justice in what Leonius described as "the expenses incurred in the works of the lord King at Vale Royal".[21][note 11]

In the early 1280s, the king greatly expanded the initial endowment, and made large donations of cash and materials.[6] Money was plentiful and work progressed quickly.[21] Initially providing 1,000 marks in cash for the project, Edward also provided the monks with revenue from his earldom of Chester; in 1281, the Justice of Chester was instructed to disburse the same amount to the monks each year.[12] Leonius moved on to other projects that year, and the abbot was placed in personal charge of the works' administration.[44] Two years later, sufficient progress had been made to allow the new church to be consecrated by the Bishop of Durham, Anthony Bek; Edward and his court attended the service.[12] The King donated a relic of the True Cross which he had captured on his crusade to the abbey.[45] In 1287 the abbot ordered a selection of marble columns and bases to be made for the cloister. These came from the Isle of Purbeck,[38] and were created by Masters John Doget and Ralph of Chichester[note 12] to Walter of Hereford's design, at a cost to the abbey of 3s. 6d. The abbot put down a deposit of £52 for the building work generally.[46] During the winter months open stonework was covered with bundled hay to protect it from the elements.[47]

Financial problems

The abbey's financing soon encountered difficulties. During the 1280s, the royal finances fell into arrears and eventually collapsed. War with Wales[48][note 13] had broken out in 1282,[8] and Edward needed money for troops and workmen to build castles, such as Harlech, which cemented the eventual conquest. He took the money which had been set aside for Vale Royal and its masons and other labourers.[48][note 14] This was around the time that construction began on the monks' cloister, for which the marble columns were intended.[15] The monks were still living in the temporary accommodation built at the start of the works.[8][note 15]

In 1290, Edward announced that he was no longer interested in the abbey: "the King has ceased to concern himself with the works of that church and henceforth will have nothing more to do with them".[50] When Walter of Hereford sent to the Wardrobe to claim the robe he was annually issued as part of his contract,[22] he was told this would be the last time, and he would receive neither wages nor robes from then on.[38] The precise reasons for the King's volte-face are unknown. Historians have speculated that the monks may have incurred his displeasure somehow, or that it was connected to the illness and death of Queen Eleanor in November the same year;[50] the art historian Nicola Coldstream has suggested that Edward had a "habit of abruptly stopping funds" for his religious projects.[51][note 16] It is possible, says The King's Works, that "some of the building money may have been used for other purposes without the King's leave".[52][note 17] Once-large royal grants became meagre,[55] and the situation was exacerbated by the abbey not receiving monies rightfully due to them. Queen Eleanor had left it a legacy of 350 marks in her will, with the intention of establishing a chantry in her name and contributing generally to the ongoing works. Twenty years later, the abbey was still owed over half this amount from her executors.[52] By 1291 they were in arrears to the tune of £1,808; the King authorised a one-off payment of £808, but the remainder went unpaid[56] until 1312, five years after King Edward's death.[57]

The monks struggled to complete and manage the vast project without royal officials.[58] Despite possessing a substantial income from its own lands and feudal dues, the abbey amassed large debts to other church institutions, royal officials, building contractors and even the merchants of Lucca.[6][note 18] Funds may have been misappropriated.[15] Work stopped for at least a decade after 1290, at least in part due to the transference of the county revenues from the abbey to the newborn Prince of Wales, who was also made Earl of Chester.[56] Workmen refused to work for fear of not being paid.[56] When the works eventually resumed they were on a much-reduced scale;[6] if the King had suspected embezzlement at the abbey, by 1305, suggests the History of the King's Works, he had "relented" sufficiently to make them a grant of £40 to pay for the roof.[53] The authors note that from then on, construction

Dragged on through the 14th and 15th centuries, an object lesson in the unreliability of princes and the folly of monks who had allowed themselves to be drawn into grandiose schemes inconsistent with the architectural simplicity which had once been one of the most cherished principles of the order.[8]

— History of the King's Works, 1963

With the accession of the Prince of Wales as King Edward II in 1307, some reimbursement for the abbey's funds arrived. £100 was sourced from The Peak, a nearby royal manor, and in 1312, they were granted £80 per annum from Ashford in the Peak. This only lasted five years, when the King granted the manor to his brother Edmund of Woodstock.[56]

Relations with tenants

No woman was able to marry outside the manor or outside her conditions of bondage without permission and a charge; when a woman became pregnant she had to make a payment to the lord; men and women could be punished for sins committed or else make a suitable payment; none could work for another without the lord's consent but were required to work for him at his will; the holding and working of land outside the manor was restricted...and, lastly, peasants were not allowed to dispose of their property by means of will or gift as their goods belonged to their lord.[59]

A. J. Bostock and S. M. Hogg

In addition to the burden of trying to finish the abbey buildings, Vale Royal faced other serious problems. As the medievalists Gwilym Dodd and Alison McHardy have emphasised, "a religious house, like any other landlord, depended on the income from its estates as the main source of its economic wellbeing",[60] and from the late 12th century, monastic institutions were "particularly assiduous in...seeking to tighten the legal definition of servile status and tenure" for its tenantry.[60] From its foundation, Vale Royal was no exception, and the monks' relationship with their tenants and neighbours soon deteriorated and remained usually poor.[11][61][note 19] The abbey was resented by the people of Darnhall and Over, who found themselves under its feudal lordship. This made the previously free tenants villeins.[note 20] Tenants of Darnhall attempted to withdraw from paying the abbot in 1275 (only a year after the abbey's foundation), and continued to feud with Vale Royal's abbots over the next fifty years.[61] The dispute was mainly caused by forestry rights; the new abbey was in the forest of Mondrem, which had been mostly common land until it was granted to the abbey. Keeping it common land would have prevented the monks from utilising it, so the abbey effectively received immunity from the foresting laws, and, say Bostock and Hogg, "almost certainly" over-reached itself regularly.[15][note 21]

Abbots were also feudal lords, and not necessarily sympathetic landlords because of their ecclesiastical position; when their tenants appeared before the abbot's manorial court, they appeared before a judge and common law applied.[69] The abbots may have been oppressive landlords, with the people responding fiercely to what historian Richard Hilton called a form of "social degradation".[70] With a generally uncertain income, and massive outgoings, the monks may have had to be harsh landlords,[71] although they apparently undertook their duties as landlords with zeal.[72] Scholars are uncertain as to whether the abbey was as harsh a landlord as the villagers claimed. Previous landlords, such as the earls of Chester, may have been lax in their enforcement of serfdom, and so Darnhall and Over probably became accustomed to their relative freedom. Alternatively, the monks may have been lax in enforcement feudal laws, leading the villagers of Darnhall and its surrounding area to take advantage of them.[73] The villagers prosecuted their struggle in earnest, sometimes in law and sometimes with violence.[74][59] They attacked monastic officials a number of times; a monk was attacked and a servant killed while collecting tithes in Darnhall in 1320 (under Abbot Richard of Evesham),[61] and Abbot Peter was killed in 1339 while defending the abbey. They made multiple approaches to both the King and Queen—often travelling great distances to do so—but to no avail.[75]

Estates and finances

The village of Over was the centre of the abbey's estates, and was (like the surrounding villages) under the abbot's feudal lordship.[28] The abbey's original endowment at Darnhall included the Delamere Forest site, the manors in Darnhall, Langwith in the East Riding of Yorkshire, and the advowsons of Frodsham, Weaverham, and Ashbourne and Castleton.[6] Further grants of land included Conewardsly in 1276, followed in 1280 by estates on the Wirral. The abbey also received manors belonging to members of the local gentry in 1285, including those of Hugh de Merton (around Over), Bradford and Guilden Sutton.[28] Ashbourne, though, was not held for long; within a few years, Vale Royal was forced to cede the advowson to Lincoln Cathedral for £400. In exchange, the king arranged for Vale Royal to receive the wealthy Kirkham Priory. Then in the possession of Shrewsbury, a combination of royal pressure and legal chicanery forced Shrewsbury to renounce its rights. According to Jeffrey Denton, "even [Vale Royal's] own chronicler cast some doubt on the justice of these proceedings".[76] The abbey had a glassmaking forge in Delamere Forest[77] which earned a small profit for the first few decades of its operation,[12] although—for now unknown reasons—it seems to have ceased production around 1309.[77]

Wool exports were the abbey's main source of income.[note 22] In 1283, Abbot Chaumpeneys acknowledged receipt of 53s 6d 8p as an advance on the abbey's eventual delivery of twelve sacks of collecta.[note 23] These transactions were made before the merchant sold the wool, with the proviso that the profit was returned to the monastery.[81] In the mid-1330s, Abbot Peter calculated that the abbey's income was £248 17s, of which £60 was spent on hospitality,[note 24] £16 on wages for the abbey's servant staff, £21 for the abbot's expenses, £30 for defensive measures, and £50 in "gifts, damages and contributions".[28] The remainder—insufficient, said Abbot Peter in 1336—was spent on the monks' everyday needs.[28] By 1342, under Abbot Robert de Cheyneston, the abbey was £20 in debt and a fire had burnt down its monastic granges at Bradford and Hefferston; the monks, who lost all the corn in the granges, had to purchase enough to live on until the next harvest.[84] Robert lamented the £100 he required to repair the granges, their weirs, portions of the church roof and the abbey building.[28]

Vale Royal's finances seem to have improved by the 15th century. Two taxes assessed the abbey at £346 0s. 4d in 1509 and, twenty-six years later, at £540 6s 2d.[6] Income was up, and expenses were down; about £92 was spent in 1509, and slightly over £21 in 1535. Although the abbey was wealthy in goods and oxen, it had many fewer monks then originally intended; the abbot of Dore, visiting Vale Royal in 1509, found fifteen resident monks instead of a reported population of thirty.[15]

Later middle ages

In spite of the abbey's financial difficulties, building continued, albeit at a slow pace, and by 1330 the monks were able to move from their "temporary"[56] dwellings into their main quarters.[56] The same year also saw the completion of the east end of the church—the remainder still a shell—and enough of the cloister buildings to make the abbey habitable, although far from complete.[27] Much of the main vault remained exposed to the Cheshire weather.[17] Royal funding had nearly dried up, and Abbot Peter complained in 1336 that vaults, cloisters, the chapter house and dormitories were yet to be built.[7] He complained that,

We have a very large church commenced by the King of England at our first foundation, but by no means finished. For at the beginning he built the stone walls, but the vaults remain to be erected together with the roof and the glass and the other ornaments. Moreover, the cloister, chapterhouse, dormitory, refectory and other monastic offices still remain in proportion to the church; and for the accomplishment of this the revenues of our house are insufficient.[56]

— Peter, Abbot of Vale Royal, The Ledger Book of Vale Royal

Abbot Robert de Cheyneston—in office between about 1340 and 1345—may have been responsible for roofing the choir and the church's north end in lead.[56]

The abbot and the community of monks moved from their temporary wooden lodgings, then "unsightly and ruinous", into the new monastic buildings. Much work still needed to be done; the vaults, roof, cloisters, chapter house, dormitory, refectory and other offices either needed to be completed or else started.[28]

A. J. Bostock and S. M. Hogg

In 1353 brought cause for renewed hope. Edward the Black Prince—King Edward III's son and heir (now the Earl of Chester)—was fully invested in his father's wars in France, and Cheshire was an important source of troops. The prince lavishly patronised the county's gentry and institutions, with Vale Royal (described by Anthony Emery as an "extravagant 'war' church") foremost among them.[85] Edward had nominally taken Vale Royal under his protection in 1340,[86] was keen to see the abbey completed. He donated substantial funds:[6][27] 500 marks in cash immediately, with the same amount paid five years later[28] when visited personally.[6] In 1359, Prince Edward granted Vale Royal the advowson and church of Llanbadarn Fawr, Ceredigion, to further finance construction.[15][note 25] William Helpeston was contracted to oversee construction[88] in August 1359,[58] for which the abbey contracted to provide—on top of his wages—board and lodging for himself and his men.[89] Their tools and fuel[89] would also be paid for.[90][note 26] He would also receive a life annuity of 40 shillings a year.[89] This work was expected to take six years, although in the event went over time:[15] a commission to impress masons in 1354 had to be renewed six years later.[89] The abbey choir was completed during the first year;[85] scholars are now uncertain as to what degree Helpeston was still building in accordance with de Hereford's 13th-century plans or was introducing elements of his own design.[1] Helpeston plans provided for an apsidal choir[88] comprising an ambulatory and thirteen chapels, seven heptagonal protruding and six, smaller rectangular chapels facing inwards.[1] There were problems with securing Helpston's continued commitment; his contract was renegotiated within the year; this time, it was specified that rather than being paid directly, the money would be paid to the abbot who would then pay Helpeston having inspected his work.[89]

Work focussed on completing the shell of the nave and developing the east end, and may have been based on a similar design for Toledo Cathedral.[15][note 27] During a great storm on 19 October 1359,[91] however, much of the nave (including the new lead roof installed by the previous abbot) was blown down and destroyed. The arcades of the unfinished nave were reduced to rubble.[92] The destruction ranged "from the wall at the west end to the bell-tower before the gates of the choir",[93] and the timber scaffolding collapsed "like trees uprooted by the wind".[93] There are no recorded indications of poor building practices or degraded fabric to the construction, and the now-destroyed nave presented its own architectural problems for rebuilding.[91]

Repairs were slowly made over the next thirteen years, and Abbot Thomas may have been responsible for the "unique chevet of seven radiating chapels",[94] which were built by de Hepleston and cost £860.[89] This was "clearly intended to be the crowning feature of the great church".[91] Work was still being done in 1368 when the Prince of Wales recommissioned the masons for the third time.[15] The remodelled church would now be smaller than before,[94] with the nave proportionally reduced in height and width.[15] The Black Prince died in 1376, and, says The King's Works, "it must have been obvious to the monks that the days of royal munificence were over".[91] Work continued on the same reduced scale took place into the reign of Richard II, who patronised the abbey on a small scale in honour of it being a royal foundation.[58] The King was reported to be "much pleased" at the reduction in both the abbey's size and cost.[95]

Repairs and construction continued sporadically into the 15th century, with an aisle installed in the middle of the church in 1422.[94] Little else is known of the abbey until the reign of King Henry VIII in the 16th century.[86]

Relations with local gentry

Relations with the gentry were no better in the later Middle Ages than they had been with the tenantry years earlier, and the gentry also often came to blows with the monks. The abbey was involved in feuds with a number of the prominent local families, frequently ending in large-scale violence.[75] During the 14th and 15th centuries, Vale Royal was beset by other scandals. Many abbots were incompetent, venal, or criminally inclined,[note 28] and the house was often grossly mismanaged. Discipline grew lax; disorder at the abbey during this period prompted reports of serious crimes, including attempted murder. Abbot Henry Arrowsmith, who had a particular reputation for lawlessness, was hacked to death in 1437 by a group of men (one of whom was the vicar of Over) in revenge for a suspected rape by one of the abbey's monks. Although the abbey was taken under royal supervision in 1439, there was no immediate improvement, and Vale Royal of the General Chapter, the international Cistercian governing body, during the 1450s. The chapter ordered senior abbots to investigate the abbey, which the abbots concluded was in a "damnable and sinister" situation in 1455.[6] Things then improved somewhat, and Vale Royal's last years were peaceful and well-ordered.[6] Some building work continued, as records attest to grants of timber for repairs were made in 1510 and 1515.[1]

The abbot of Dore visited Vale Royal in 1509[86]—by which time the abbey held 19 monks[96]—and made a brief inventory of its rooms, including the Abbot's chambers (which were described as containing "a suitable couch, ten coverlets, four mattresses, two feather beds and twelve pairs of linen sheets").[86] According to archaeologist S. J. Moorhouse, luxuries such as these indicate how far the Cistercian focus had drifted from the order's original asceticism.[86]

Last abbatial election

Abbot John Butler died in summer 1535. The election of his replacement indicates the extent to which the local gentry interfered in the house's internal affairs. William Brereton and Piers Dutton—local knights and rivals for regional power in the county—both proposed their own candidates. The election became mired in corruption; Dutton's man, for example, offered Thomas Cromwell—Henry VIII's chief minister—£100 and promised to him "as large pleasure as any man"[97] in future. Adam Beconsall and Thomas Legh—the monastic visitor, who himself had accepted a £15 bribe—backed one John Hareware,[97] the former abbot of Hulton Abbey.[98] Furthermore, Queen Anne Boleyn herself also favoured a particular candidate. In the event, King Henry ordered a free election, and this saw Hareware elected. Although his candidate had lost, Brereton still managed to wrangle granted an annual pension of £20 from Hareware for the rest of Brereton's life. More importantly for the new abbot, Cromwell was appointed steward of the abbey by the King.[97] In common with many other monasteries—by now aware of their impending dissolution—Hareware began raising ready cash. This was done by means of negotiating long tenancies for their lands at very low rents in exchange for high entry fees.[note 29]

Dissolution

By 1535 Vale Royal was one of only six monastic institutions remaining in Cheshire.[100][note 30] It was reported that year's Valor Ecclesiasticus as possessing an income of £540, making it the wealthiest of the 13th-century Cistercian foundations and the fourth-wealthiest overall.[101] Much of the income seems to have been increasingly used for bribing the local gentry and providing them with pensions.[102] The income enabled Vale Royal to escape dissolution under the First Suppression Act, King Henry VIII's initial move in the Dissolution of the Monasteries, by which time its population had declined to 15 monks.[96]

Abbot John Hareware pursued a two-pronged policy of attempting to ensure the abbey's survival and, if that failed, the security of himself and his brethren. Hareware bribed courtiers, influential nobles and (in particular) chief minister Thomas Cromwell with money and property in an attempt to gain a respite for the abbey, and leased most of the abbey lands to friends and associates of the monastery to keep them out of royal hands if the abbey fell. Many of the leases had a clause voiding them if the abbey survived. Hareware sold its other assets, such as livestock and timber, for cash.[6]

The process of dissolution at Vale Royal was begun in September 1538 by the royal commissioner Thomas Holcroft,[6] who was ordered to "take and recyve" the abbey from Hareware.[103] The situation grew legally murky as Holcroft, probably with a forged signature on the deed of exchange,[104][note 31] claimed that the abbey had surrendered to him on 7 September. The abbot (and abbey) denied doing so, questioning Holcroft's authority. Holcroft then alleged that the abbot had attempted to take over the abbey himself, and had tried to conspire with Holcroft to commit land fraud.[6] The monks continued to petition the government, particularly Thomas Cromwell, who was responsible for church affairs in his role as vicar general during the Royal Supremacy. Hareware wrote to the chief minister during his journey to London:

My Good Lord, the truth is, I nor my said brethren have never consented to surrender our monastery not yet do, nor never will by our good wills unless it shall please the King's grace to give us commandment to do so.

In December 1538, Abbot John and his community received a papal dispensation to change habits and temporarily join another order.[104] With some disquiet probable in government circles about the legitimacy of the Vale Royal surrender, steps were taken to put the matter beyond doubt. A special court was held at the abbey on 31 March 1539, with Cromwell the judge. Instead of investigating the circumstances of the surrender[106] the court charged the abbot with treason and conspiracy in the murder of a monk (who had committed suicide) in 1536.[104] He was also accused of "treasonous utterances" during the Pilgrimage of Grace; both murder and treason were capital crimes.[note 32] The abbot was found guilty, and Vale Royal was declared forfeited to the crown.[106] Abbot John was not executed: rather, he was given a substantial pension of £60 per year and the abbey's silver plate, indicating that the trial was a means of pressuring him to acquiesce to Cromwell.[6][106] The rest of the community were also pensioned off, and Exchequer records indicate that Abbot John lived until at least 1546.[6] The abbey's immediate estates were incorporated into the new parish of Whitegate.[108]

Later history

After protracted negotiations with the crown,[103] Thomas Holcroft leased Vale Royal. Previously an obscure member of the lower Cheshire gentry, the acquisition made him a man of substance.[109] In 1539 he demolished the church, telling King Henry in a letter that it was "plucked down".[27][note 33] On 7 March 1544, the King confirmed Holcroft's ownership by granting him the abbey and much of its estates for £450.[27][111] Holcroft further removed many of the abbey's domestic buildings, retaining the south and west cloister ranges—including the abbot's house and the monks' dining hall and kitchen—as the core of his mansion[27] (which was centred on the abbey cloister).[103] Holcroft built a grand external staircase to his new first-floor entrance, which, suggests the archaeologist J. Patrick Greene, "reinforced the visual reminder to all visitors that a new regime now prevailed" at Vale Royal.[112] Holcroft retained the abbey gatehouse as the courtyard's entrance, and leased the abbey and its lands until he was knighted in 1544 when he purchased it outright.[113]

Holcroft's heirs lived at Vale Royal until 1615.[106] During their residency canted bay windows were introduced to the front of the wings which, along with their accompanying mullions and transoms, have been described by Pevsner as "a remarkably early instance of Elizabethan revivalism". It was also around this time that the "crude gothic porch" of Holcroft's was moved to the ground floor.[1] At this date the house came into the hands of the Cholmondeley family (later Lords Delamere).[114] Mary Cholmondeley (1562–1625), a powerful widow with extensive properties in the area, bought the abbey as a home for herself when her eldest son inherited the primary family estates at Cholmondeley. In August 1617, she entertained James I and a stag-hunting party at Vale Royal.[106] The king enjoyed himself so much that he knighted two members of the family and, in a letter written shortly after his visit, offered to advance the political careers of Lady Mary's sons if they would come to court. His offer was so firmly refused that the King called her "the Bolde Lady of Cheshire".[115] Mary passed the abbey and estate to her fourth son, Thomas (who founded the family's Vale Royal branch), at her death in 1625.[116]

During the English Civil War, the Cholmondeleys supported Charles I.[116] Their allegiance had serious consequences; fighting took place at Vale Royal, the house was looted, and the building's south wing was burned down by Parliamentarian forces commanded by General John Lambert.[117]

Despite this, the Cholmondeley family continued to live in the abbey. A southeast wing, designed by Edward Blore, was added to the building in 1833. In 1860, Hugh Cholmondeley, Baron Delamere, commissioned Chester architect John Douglas to recast the centre of the south range (which had been timber-framed). Douglas added a southwest wing the following year and altered the dining room.[118] The church of St Mary, the capella extra portis (chapel outside the abbey gates), remained opposite the west lodge. The church was largely rebuilt in 1728, incorporating fabrica ecclesiae from a timber-framed church probably dating to the 14th century. In 1874–1875 Douglas remodelled St Mary's, changing its external appearance but retaining much of the internal structure.[119]

The Cholmondeley family lived in the abbey for over 300 years.[120][121] In 1907 they rented it to a wealthy Manchester businessman Robert Dempster.[122] Dempster had made his fortune from R & J Dempster and Sons, a gas-engineering company he founded in 1883. His second daughter, Edith, was born that year and lived at Vale Royal with her father until his 1925 death in South Africa. He was buried at Whitegate Church, near the abbey. Edith inherited half of his fortune and all of his personal effects, including the lease on Vale Royal. In the spring of 1926, she married Frank Pretty at Whitegate Church. Edith gave up the lease on Vale Royal and purchased the relatively modest Sutton Hoo estate later that year. Frank died at the end of 1934; Edith hired archaeologist Basil Brown to excavate some of the mounds on the Sutton Hoo estate in 1939, discovering northern Europe's richest Anglo-Saxon burial ground.[123]

Another Cholmondeley, Thomas, Baron Delamere, moved into the abbey in 1934; he was forced out in 1939, when the government took over Vale Royal to use as a sanatorium for convalescing soldiers during World War II.[122] The Cholmondeleys regained the abbey after the war before selling it to Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI) in 1947.[124] The company initially used the abbey as staff accommodation and, from 1954 to 1961, as the headquarters of its salt[58] and alkali division.[125] In 1958 they permitted (and assisted with labour and facilities) an extensive archaeological excavation, which was intended to complete an earlier dig of 1911–1912.[16]

ICI moved out in 1961. There were abortive schemes to use the abbey as a health centre, a country club, a school and a prison. In 1977, the abbey became a residential care home for people with learning disabilities.[125] In 1998, Vale Royal became a private golf club.[126] A proposal to turn the house into flats led to a detailed 1998 archaeological study by the Chester Archaeological Society.[110]

Archaeological investigations and discovery of remains

Nothing remains of the great church and "virtually nothing"[127] of the other ecclesiastical buildings, although archaeological work has revealed many details of the church's structure.[120] According to A. Emery, "detailed examination of the roof ... has revealed hidden structural evidence beneath layers of post-medieval changes".[127] Excavations by the Manchester architect Basil Pendleton were made in 1911–1912,[17] which he focused around the Nun's Grave. Pendleton established that the church had been 421 feet (128 m) long, with a decoratively floored 92-foot (28 m) nave. The combined width of the east and west transepts was 232 feet (71 m).[15] The remainder of the construction was, at various times, around a grassed quadrangle—possibly a 140-foot-square (43 m) herb garden. Apart from the church (which took up the east side of the square), the buildings consisted of a chapter house,[note 34] the abbot's dwelling, guest accommodations, and the outbuildings necessary for the upkeep of the community and its agricultural work.[130] Much of the abbey's stonework was sold by Holcroft when it was destroyed.[58] Some was used to build a common well;[103] at least one domestic garden in Northwich contained original carvings and bosses,[131] and abbey stones were found in the walls of three other houses.[103] It is possible that the ceiling of Weaverham church's north aisle came from Vale Royal.[132] Holcroft also rebuilt the western grange for his own use with stone from the church.[88] The south wing of the extant building incorporates the original refectory roof, which has been dendrochronologically dated to the second half of the 15th century. It consisted, writes Emery, "of a timber-framed three-bay hall, open to the roof, flanked by a pair of single bay rooms, the whole set above a masonry ground floor".[127] The 1958 excavation uncovered the 1359 additions, including the chevet apse.[17] Pieces of stained glass were uncovered in Delamere Forest,[77] while Purbeck marble and other architectural fragments were also found.[88]

Historian Jeffrey Denton has suggested that Vale Royal Abbey has been relatively unexamined by scholars because of its near-total mid-16th-century destruction; "had it survived, our views of Edward I's relations with the Church may well have been radically different".[19] A circular stone monument, known as the Nun's Grave, reportedly commemorates Sister Ida, thought to be a 14th-century Cheshire nun who nursed an unnamed Vale Royal abbot, and who was buried at the high altar.[15] The monument was erected by the Cholmondeley family, possibly to lend credence to the legend of the nun. The material in its construction is from three sources: the head from a medieval cross whose four panels depict the crucifixion, the virgin and child Jesus, St. Catherine and St. Nicholas; the shaft, made of sandstone in the 17th century; and a plinth from a reclaimed[133] pillar base. Pevsner's Buildings of England has described the monument as looking "convincingly late 13th-century",[1] and notes other remnants of pillars around the grounds "of great size and elaboration".[1] The present country house on the site incorporates parts of the south and west ranges;[134] the former has a door arch from the abbey, one of the few elements of the original abbey which is still visible.[58] At least some of the original abbey still survives to the first floor; in 1992 a British Archaeological Association study discovered late-medieval graffiti scratched into plasterwork on an internal wall.[135][note 35] Holcroft's Tudor house also stands. The building is a Grade II* listed building,[136] and St Mary's church is listed at Grade II,[134] while what remains of Vale Royal Abbey is a scheduled ancient monument.[120][121][136]

See also

- Abbot of Vale Royal

- Grade II* listed buildings in Cheshire West and Chester

- Listed buildings in Whitegate and Marton

- List of houses and associated buildings by John Douglas

- Round Tower Lodge

Notes

- ^ Vale Royal's chronicle was written during the early 14th century, and while its precise authorship is unknown, its beginning at least is often ascribed to Peter, Abbot of Vale Royal, around 1338. This is based on some textual indications but also, said John Brownbill, who edited it for publication in 1914, the fact that it was clearly written by someone who on the one hand had access to oral histories on the earliest days of the abbey but without personal knowledge, combined with mentions of buildings which had been built by then (and, perhaps even more significantly, the omission of mention of structures built after 1340). Known as the Ledger book, it records not only the Abbey's history and its abbots up to 1338, but also the abbey's litigation records and papal bulla granted to the Cistercians.[2]

- ^ The chronicler describes the train of events in some detail: "while [Edward] was on his way to England, accompanied by a great concourse of people, storms suddenly arose at sea, the ship's rigging was all torn to pieces in a moment, and the crew were helpless and unable to do anything. Utterly despairing of their safety, the sailors called loudly upon the Lord ...[Edward] most humbly vowed to God and the Blessed Virgin Mary that, if God would save him and his people and goods, and bring them safe to land, he would forthwith found a monastery of white monks of the Cistercian order in honour of Mary the Mother of God ... for the maintenance of one hundred monks for ever. And behold, the power of God to save His people was forthwith made manifest; for scarce had the most Christian prince finished speaking when the tempest was utterly dispersed and succeeded by a calm, so that all marvelled at so sudden a change. Thus the ship ... was miraculously borne to land by the Virgin Mary, in whose honour the prince had made his vow, without any human aid whatsoever ... until they had all carried their goods safe out of the ship, the prince remained behind them in the ship, but as soon as the ship was empty, he left it and went on shore; and as he left, in the twinkling of an eye, the ship broke into two pieces".[2]

- ^ Sir James Ramsay was more specific, dating the crossing to the period between Christmas and New Year's 1263 (when Edward sailed from Calais to Dover ahead of his father, who is known to have travelled on 2 January 1264.[5]

- ^ It has also been suggested that the original site was uncomfortably distant from a freshwater source sufficient for a large community; Darnhall was on Ash Brook (a minor waterway), and Vale Royal was near the River Weaver and its two substantial tributaries.[12]

- ^ Walter de Hereford worked on the abbey from 1277 to 1290, in an exclusive contract to the crown,[22] received a wage of two shillings per day—nearly £37 per annum.[23] He was also exempted from the customary rule that wages were reduced during the winter on account of the shorter days; masons paid about 12d a week during the summer, received 9d a week in the winter months.[24] He received almost five times the wage of the next-highest-paid carving masons.[21] He also had his robes provided for him.[22] De Hereford was likely responsible for the use of decorated mouldings in the church,[25] which he later brought to his work during the construction of Caernarfon Castle.[26]

- ^ Although seemingly a contradiction, Knoop and Jones suggest that the explanation is that a large number of the masons Walter originally recruited were of low grade, and, therefore, there was a high turnover. With the subsequent recruitment of better masons, however, fewer were needed, as they were more skilled.[33]

- ^ Although this may not be a genuine decrease in the amount of work taking place as the original figure probably includes men who were initially employed and either whose skill was found wanting or who chose not to stay.[21] On average, in any one month, construction required 135 men: 40 masons, 4 carpenters, 15 quarrymen, 36 diggers, 7 blacksmiths and 33 carters.[34] The average length a mason's employment was 11.1 months; this compares to much-decreased tenures from lower grades, for example, quarrymen, carters and carpenters, who were employed for an average of 6.5, 4.3 and 3.4 months respectively.[35] In some cases men appear to have worked for only a few days before moving on; the architectural historians Douglas Knoop and G. P. Jones have suggested that itinerant masons were probably being given a few days work in order to fund their onward travels.[36]

- ^ Three grades of workmen—Masters, Cutters and Trimmers—worked in a gang at the quarry to trim the stone down before it was transported to site to be finally shaped.[38] There was also a separate blacksmith's forge for the repair and maintenance of the quarrymen's tools.[39]

- ^ Since Vale Royal was isolated, the dwellings were for construction workers as well as the monks.[20] Between 1277 and 1280 at least three mason's workshops and two lodges were erected for those workers.[36]

- ^ This, says the King's Works, was made easier for Edward by the abbey's location; he intended that the works should be financed through royal county revenues, and the fact that Cheshire was a county palatinate "made it easy for him to divert its revenues" for this purpose.[21]

- ^ Leonius's receipts and records are still extant. They are held in the National Archives in Kew, classed as E 101/485/22.[43]

- ^ Much of Ralph's business was connected to Vale Royal, which regularly sold ready-made stone components. Other royal projects included the King's Eleanor Crosses, for which he provided the cross shafts. Although historians have been unable to establish John Doget's identity, A. J. Taylor says "it is not unlikely that he is the same as the John of Corfe who was another supplier, with Ralph of Chichester, of marble for Charing Cross". [46]

- ^ For this reason, the justiciar, Reginald de Grey, who was bound to pay the abbot £1,000 yearly towards the building, "was obliged by the Welsh revolt to divert nearly the whole of the first years' farm to military purposes". From then until 1284 Vale Royal "received less than half the £2,000" intended for it.[44]

- ^ The Justiciar of Chester was enjoined to "cause 100 suitable masons experienced in such work as the King is engaged upon at Kaernaruan to be chosen in the town of Chester and in other parts within his bailiwick, and cause them to come with their tools to Kaernaruan without delay, there to do what Edmund the King's brother shall enjoin upon them, as the King needs masons for his works there at once".[49]

- ^ There were increasing problems with the abbey's workmen as well at this time; for example, in 1285 "much trouble was caused by the imprisonment of a mason named John of Dore, who, along with other Vale Royal workmen, was accused of taking venison in Delamore Forest".[38]

- ^ Coldstream notes, for example, that he did the same thing to his creation of St Stephen's Chapel in 1297.[51]

- ^ The authors make this suggestion based on Edward's granting of some funds in 1290 to cover the abbey's arrears, but with the proviso that the Exchequer took special care to independently establish that the money was spent "on abbey works and not for other purposes".[53] Indeed, funds became so short for this project that in 1332 workmen downed tools to force payment of unpaid wages.[54]

- ^ The abbey had experienced financial problems since its foundation; although it had been granted a licence in 1275 to sell wool to pay for construction, seven years later the abbey owed £172 to merchants. By 1311, £200 was still owed to a custodian of the works from a 1284 debt.[6]

- ^ The extent to which this concerned the monks, particularly in the early years, has been questioned. Cistercians, it has been noted, "were not normally too bothered by that as they had a reputation as de-populators and often uprooted whole communities".[28]

- ^ During the early Middle Ages, villeins were serfs who were tied to the land they worked and could not leave (or stop working) the land without permission from the lord of the manor. By the late 14th century, villeinage was less burdensome than it had been two centuries earlier; less heavy labour was required. It was still possible for a lord to insist on one-third of a tenant's goods at the latter's death, and Vale Royal did so frequently.[62] Since they were not freemen, villeins did not have recourse to trial by jury,[63][64][65] that "despite the light labour services associated with villein tenure, there is no doubt that the personal and financial liabilities could weigh heavily".[66] Villagers in Darnhall and Over were required to pay "redemption" to the abbey when a daughter married.[67]

- ^ This involved the right to clear forest land for agricultural purposes and to remove timber and branches.[59] The historians Dodd and McHardy have described how, from the point of view of an ecclesiastical landlord, "the impositions made on their tenants were entirely legitimate, lawful and moral; challenges against their authority...represented a 'disinheritance' of their rights and an affront to the natural social order".[68]

- ^ The Cistercians specialised in wool production, and, argues the economist Gillian Hutchinson, were mainly responsible for the growth of the medieval English wool trade and its eventual pre-eminence in Europe by the 15th century.[78]

- ^ Wool the abbey gathered from outside its estate, such as local farms. The distinction was important to merchants since abbey wool was the only wool perceived as reliable in quality.[79] Historian T. H. Lloyd has described the process operating at Darnhall Abbey in 1275, when the monks contracted "to supply 12 sacks of Herefordshire collecta as good as the better collecta of Dore Abbey. The wool was to be dressed at Hereford by a man sent and probably paid, by the merchant, but the abbey was to find his board while he engaged in the work. The price of this wool was only 9 marks a sack, including delivery to London".[80]

- ^ Hospitality was a primary duty for those under Benedictine rule, such as the Cistercians; St Benedict taught, "let all guests be received as Christ himself".[82] However, "the cost of entertaining guests on ceremonial occasions hosted by the community was considerable".[83]

- ^ This, a common practice beginning in the 14th century, was a convenient device to relieve a religious house of its debts; according to historian F. R. Lewis, 539 such grants were made during Edward III's reign.[87]

- ^ The contract notes that this is "because it is the custom that their tools, if they bring any, shall be bought".[36]

- ^ Another royal Cistercian foundation, Hailes Abbey, had a similar radiating east end;[1] The King's Works suggests that "though diplomatic contacts between the Black Prince and Castile could explain how he or his master mason became aware of this unusual plan, it is more likely that the immediate prototype was some church in Gascony or southwest France now destroyed, but familiar to the English rulers of Aquitaine in the 14th century".[89] Another continental influence came from the abbey of St Urbain in Troyes—also dating from the late 13th century—from which came Vale Royal's distinctive pier bases. [1]

- ^ Abbot Stephen (in office 1373 – c. 1400) was involved in violent fighting with the Bulkeley family of Cheadle in 1375. He provided sanctuary to a convicted murderer in 1394; was regularly accused of preventing the arrest or prosecution of his monks; accepted bribes to allow prisoners to escape, and illegally felled trees for profit. In 1395, a commission discovered that he had impoverished the abbey over the previous decade by selling, alienating, and destroying its estates. Two of Stephen's monks were accused of theft and rape, respectively.[6]

- ^ Such a strategy often resulted in extremely long alienations of church property. In 1535, for example, Hareware had leased the abbey's Castleton manor out for 70 years. Soon after dissolution, the first Bishop of Chester, John Bird, also leased it, consecutively, for another 99 years, meaning that Castleton was not regained by the Church of England until 1704.[99]

- ^ Apart from Vale Royal, the rest were another Cistercian foundation at Combermere Abbey, one nunnery in Chester, two Benedictine establishments in Chester and Birkenhead, and an Augustinian house at Norton Abbey.[100]

- ^ The Abbot himself pointed out, in a letter to Cromwell after the Abbey's surrender, that the signature on the instrument of surrender was different to that on an earlier charter Hareware had signed.[105]

- ^ The abbot was accused of condoning the murder of Brother Hugh Chalner. According to the prosecution, Chalner had told his 12-year-old nephew that he was leaving the abbey to join the boy's father in Chester and feared for his life in Vale Royal. The following day, Chalner was found dead with his throat cut.[107] The accusation that Harewood supported the Pilgrimage of Grace stems from the fact that his brother had told the abbey's tenants, "I can showe to you goode tydynges, for the commyns be up" because King Henry "did ouerpresse the poore commyns". In spite of this, much of the tenantry rallied to the King's banners, which supposedly angered Harewood. The abbot was also supposed to have denied the legality of Henry's marriage to Boleyn.[102]

- ^ According to J. Patrick Greene, "the Tudor purchasers of dissolved monasteries were often looking for buildings that would form the basis of a country house surrounded by a ready-made estate".[110] Holcroft was an exception to this rule in Cheshire, however; unlike the rest of the country, most of the ecclesiastical land remained in the hands of the crown or helped form the recently created Diocese of Chester.[109]

- ^ The chapter house, "a place second in importance to the church itself", was where the abbey's main business (religious—the monks read chapters of St Benedict's teachings and confessed publicly to each other—[128]and, especially, administrative)[129] was conducted; the manorial court was held there.[28]

- ^ This consists of a graffito with the name "Alexander", and, says Nigel Ramsay, is "difficult to date, partly because their letterforms did not necessarily represent those in use in contemporary handwriting". It is, however, "unquestionably medieval...[and] probably earlier". It was also a common name for new monks entering religion.[135]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Pevsner et al. 2012, p. 647.

- ^ a b c Brownbill 1914, pp. v–x.

- ^ Prestwich 2004.

- ^ a b Denton 1992, p. 124.

- ^ Ramsay 1908, p. 210.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u VCH 1980, pp. 156–165.

- ^ a b c d e Turner & McNeil-Sale 1988, p. 53.

- ^ a b c d Brown, Colvin & Taylor 1963, p. 248.

- ^ a b c d e Robinson et al. 1998, p. 192.

- ^ Williams 1976, p. 14.

- ^ a b Brownbill 1914, p. vi.

- ^ a b c d e f Bostock & Hogg 1999, p. 1.

- ^ Powicke 1991, p. 412.

- ^ Pevsner et al. 2012, p. 646.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Bostock & Hogg 1999, p. 2.

- ^ a b Thompson 1962, p. 183.

- ^ a b c d Steane 1993, p. 164.

- ^ Palliser 2004, p. 5.

- ^ a b Denton 1992, pp. 123–124.

- ^ a b c Greene 1992, p. 71.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Brown, Colvin & Taylor 1963, p. 249.

- ^ a b c Brown, Colvin & Taylor 1963, p. 205.

- ^ a b Knoop & Jones 1933, p. 6.

- ^ Knoop & Jones 1933, pp. 18–19.

- ^ Maddison 2015, p. 1.

- ^ Maddison 2012, p. 1.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Robinson et al. 1998, p. 193.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Bostock & Hogg 1999, p. 3.

- ^ Lindley 2003, p. 1.

- ^ Coldstream 2008, p. 7.

- ^ Steane 1993, p. 50.

- ^ Knoop & Jones 1933, p. 29.

- ^ Knoop & Jones 1933, p. 28.

- ^ Knoop & Jones 1933, p. 15.

- ^ Knoop & Jones 1933, p. 27.

- ^ a b c Knoop & Jones 1933, p. 30.

- ^ Greene 1992, p. 70.

- ^ a b c d e f Brown, Colvin & Taylor 1963, p. 250.

- ^ Knoop & Jones 1933, p. 17.

- ^ VCH 1980, p. 192.

- ^ Brown, Colvin & Taylor 1963, p. 161 n.6.

- ^ Brown, Colvin & Taylor 1963, p. 187.

- ^ Brown, Colvin & Taylor 1963, p. 249 n.3.

- ^ a b Brown, Colvin & Taylor 1963, p. 251.

- ^ Greene 1992, p. 95.

- ^ a b Taylor 1949, p. 295.

- ^ Knoop & Jones 1933, p. 22.

- ^ a b Platt 1994, p. 65.

- ^ Brown, Colvin & Taylor 1963, p. 378.

- ^ a b Palliser 2004, p. 6.

- ^ a b Coldstream 2014, p. 7.

- ^ a b Brown, Colvin & Taylor 1963, p. 252.

- ^ a b Brown, Colvin & Taylor 1963, p. 252 n.2.

- ^ Brown, Colvin & Taylor 1963, p. 186.

- ^ Prestwich 2003, p. 35.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Brown, Colvin & Taylor 1963, p. 253.

- ^ Brown, Colvin & Taylor 1963, p. 252 n.5.

- ^ a b c d e f Thompson 1962, p. 184.

- ^ a b c Bostock & Hogg 1999, p. 5.

- ^ a b Dodd & McHardy 2010, p. xxviii.

- ^ a b c Hewitt 1929, p. 166.

- ^ Bennett 1983, p. 92.

- ^ Harding 1993, pp. 74–76.

- ^ Faith 1999, pp. 245–265.

- ^ Hatcher 1987, pp. 247–284.

- ^ Booth 1981, pp. 4–5.

- ^ CCC 1967, p. 89.

- ^ Dodd & McHardy 2010, p. xxx1.

- ^ Hewitt 1929, p. 168.

- ^ Hilton 1949, p. 128.

- ^ Firth-Green 1999, p. 166.

- ^ Morgan 1987, p. 77.

- ^ Brownbill 1914, p. 186.

- ^ Hilton 1949, p. 161.

- ^ a b Heale 2016, p. 260.

- ^ Denton 1992, p. 131.

- ^ a b c Marks 2006, p. 30.

- ^ Hutchinson 1994, p. 89.

- ^ Bell, Brooks & Dryburgh 2007, p. 51.

- ^ Lloyd 1977, p. 296.

- ^ Bell, Brooks & Dryburgh 2007, p. 28.

- ^ Kerr 2008, p. 25.

- ^ Kerr 2007, p. 188.

- ^ Donnelly 1954, p. 443.

- ^ a b Emery 2000, p. 472.

- ^ a b c d e Turner & McNeil-Sale 1988, p. 54.

- ^ Lewis 1938, pp. 24–25.

- ^ a b c d Turner & McNeil-Sale 1988, p. 52.

- ^ a b c d e f g Brown, Colvin & Taylor 1963, p. 254.

- ^ Knoop & Jones 1933, p. 12.

- ^ a b c d Brown, Colvin & Taylor 1963, p. 256.

- ^ Lewis 1938, p. 25.

- ^ a b Colvin 1963, p. 256.

- ^ a b c Midmer 1979, p. 315.

- ^ Brown, Colvin & Taylor 1963, p. 257.

- ^ a b Cox 2013, p. 72.

- ^ a b c Cox 2013, pp. 72–73.

- ^ VCH 1980, p. 162.

- ^ Cox 2013, p. 130.

- ^ a b Cox 2013, p. 66.

- ^ Denton 1992, p. 129.

- ^ a b Cox 2013, p. 79.

- ^ a b c d e Guinn-Chipman 2013, p. 30.

- ^ a b c Guinn-Chipman 2013, p. 17.

- ^ Cox 2013, p. 126.

- ^ a b c d e Holland et al. 1977, p. 19.

- ^ Guinn-Chipman 2013, pp. 17–18.

- ^ Cox 2013, p. 251 n.120.

- ^ a b Phillips & Smith 1994, p. 21.

- ^ a b Greene 1992, p. 191.

- ^ Holland et al. 1977, p. 37.

- ^ Greene 2000, p. 152.

- ^ Greene 2000, p. 155.

- ^ Holland et al. 1977, p. 20.

- ^ Holland et al. 1977, p. 21.

- ^ a b Holland et al. 1977, p. 22.

- ^ Holland et al. 1977, p. 23.

- ^ Hubbard 1991, p. 40.

- ^ Hubbard 1991, p. 124.

- ^ a b c Historic England & 72883.

- ^ a b Historic England & 1016862.

- ^ a b Holland et al. 1977, p. 32.

- ^ Hopkirk 1975, pp. xxxvi–xxxviii.

- ^ Holland et al. 1977, pp. 25, 32.

- ^ a b Holland et al. 1977, p. 25.

- ^ VRA 2019.

- ^ a b c Emery 2000, p. 42.

- ^ Stalley 1999, p. 188.

- ^ Hamlett 2013, p. 117.

- ^ Bostock & Hogg 1999, p. 4.

- ^ Turner & McNeil-Sale 1988, pp. 51–52.

- ^ Cox 2013, p. 148.

- ^ Latham 1993, p. 127.

- ^ a b Historic England & 1160911.

- ^ a b Ramsay 2000, p. 167.

- ^ a b Historic England & 1160862.

Bibliography

- Bell, A. R.; Brooks, C.; Dryburgh, P. R. (2007). The English Wool Market, c.1230–1327. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-13946-780-3.

- Bennett, M. J. (1983). Community, Class and Careers. Cambridge Studies in Medieval Life and Thought. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-52152-182-6.

- Booth, P. H. W. (1981). The Financial Administration of the Lordship and County of Chester, 1272–1377. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-71901-337-9.

- Bostock, A. J.; Hogg, S. M. (1999). Vale Royal Abbey and the Cistercians 1277–1538. Northwich: Northwich & District Heritage Society. OCLC 50667863.

- Brown, R.A.; Colvin, H.; Taylor, A. J. (1963). The History of the King's Works (1st ed.). London: H.M. Stationery Office. OCLC 489821943.

- Brownbill, J., ed. (1914). The Ledger Book of Vale Royal Abbey. Manchester: Manchester Record Society. OCLC 920602912.

- CCC (1967). Cheshire under the Three Edwards. A History of Cheshire. Vol. V. Chester: Cheshire Community Council. OCLC 654681852.

- Coldstream, N. (2008). "Cross". Oxford Art Online. doi:10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.T020389. ISBN 978-1-884446-05-4. Archived from the original on 9 April 2019. Retrieved 9 April 2019.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - Coldstream, N. (2014). "Plantagenet, House of family". Oxford Art Online. doi:10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.T068034. ISBN 978-1-884446-05-4. Archived from the original on 9 April 2019. Retrieved 9 April 2019.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - Colvin, H. (1963). The History of the King's Works. Ministry of Public Building and Works. Vol. I. London: HM Stationery Office. OCLC 10780171.

- Cox, P. J. (2013). Reformation Response in Tudor Cheshire c.1500–1577 (PhD thesis). University of Warwick. OCLC 921055725.

- Denton, J. (1992). "From the Foundation of Vale Royal Abbey to the Statute of Carlisle: Edward I and Ecclesiastical Patronage". In P. R. Coss (ed.). Thirteenth Century England IV: Proceedings of the Newcastle Upon Tyne Conference 1991. Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer Ltd. pp. 123–139. ISBN 978-0-85115-325-4.

- Dodd, G.; McHardy, A. K. (2010). "Introduction". Petitions to the Crown from English Religious Houses, C.1272-c.1485. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. pp. xi–xlix. ISBN 978-0-90723-972-7.

- Donnelly, J. (1954). "Changes in the Grange Economy of English and Welsh Cistercian Abbeys, 1300–1540". Traditio. 10: 399–458. doi:10.1017/S0362152900005924. OCLC 557091886. S2CID 152058350.

- Emery, A. (2000). Greater Medieval Houses of England and Wales, 1300–1500: East Anglia, Central England and Wales. Vol. II. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-52158-131-8.

- Faith, R. (1999). The English Peasantry and the Growth of Lordship. London: Leicester University Press. ISBN 978-0-71850-204-1.

- Firth-Green, R. (1999). A Crisis of Truth: Literature and Law in Ricardian England. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-81221-809-1.

- Greene, J. P. (1992). Medieval Monasteries. London: Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-0-82647-885-6.

- Greene, J. P. (2000). "The Impact of the Dissolution on Monasteries in Cheshire: The Case of Norton". In Thacker, A. (ed.). Medieval Archaeology, Art and Architecture at Chester. Leeds: British Archaeological Association. pp. 152–166. ISBN 978-1-902653-08-2.

- Guinn-Chipman, S. (2013). Religious Space in Reformation England: Contesting the Past. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-31732-140-8.

- Hamlett, L. (2013). "The Twin Sacristy Arrangements in Palladio's Venice: Origins and Adaptions". In Avcioglu, N.; Jones, E. (eds.). Architecture, Art and Identity in Venice and its Territories, 1450–1750: Essays in Honour of Deborah Howard. London: Routledge. pp. 105–126. ISBN 978-1-35157-595-9.

- Harding, A. (1993). England in the Thirteenth Century. Oxford: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-52131-612-5.

- Hatcher, J. (1987). "English Serfdom and Villeinage: Towards a Reassessment". In T. H. Aston (ed.). Landlords, Peasants and Politics in Medieval England. Cambridge University Press. pp. 247–285. ISBN 978-0-52103-127-1.

- Heale, M. (2016). The Abbots and Priors of Late Medieval and Reformation England. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19870-253-5.

- Hewitt, H. J. (1929). Mediaeval Cheshire: An Economic and Social History of Cheshire in the Reigns of the Three Edwards. Manchester: Manchester University Press. OCLC 29897341.

- Hilton, R. H (1949). "Peasant Movements in England before 1381". The Economic History Review. New Series. 2 (2): 117–136. doi:10.2307/2590102. JSTOR 2590102. OCLC 47075644.

- Historic England. "Vale Royal Abbey (1016862)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 5 September 2012.

- Historic England. "Vale Royal Abbey (1160862)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 5 September 2012.

- Historic England. "Vale Royal Abbey (72883)". Research records (formerly PastScape). Retrieved 5 September 2012.

- Historic England. "Church of St Mary, Whitegate and Marton (1160911)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 5 September 2012.

- Holland, G. D.; Hickson, J. N.; Vose, R. Hurst; Challinor, J. E. (1977). Vale Royal Abbey and House. Winsford: Winsford Local History Society. OCLC 27001031.

- Hopkirk, Mary (1975). Bruce-Mitford, Rupert (ed.). The Sutton Hoo Ship-Burial: Excavations, Background, the Ship, Dating and Inventory. Vol. I. London: British Museum Publications. pp. xxxvi–xxxviii. ISBN 978-0-71411-334-0.

- Hubbard, Edward (1991). The Work of John Douglas. London: The Victorian Society. ISBN 978-0-90165-716-9.

- Hutchinson, G. (1994). Medieval Ships and Shipping. Leicester: Leicester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7185-1413-6.

- Kerr, J. (2007). Monastic Hospitality: The Benedictines in England, C.1070-c.1250. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-326-0.

- Kerr, J. (2008). "Cistercian Hospitality in the Later Middle Ages". In Burton, J. E.; Stöber, K. (eds.). Monasteries and Society in the British Isles in the Later Middle Ages. Woodbrige: Boydell & Brewer Ltd. pp. 25–39. ISBN 978-1-84383-386-4.

- Knoop, D.; Jones, G. P. (1933). "The First Three Years Of The Building Of The Vale Royal Abbey, 1278–1280: A Study in Operative Masonry". Ars Quatuor Coronatorum: Transactions of the Quatuor Coronati Lodge. XIV: 5–47. OCLC 607908704.

- Latham, F. A., ed. (1993). Vale Royal. Whitchurch, Shropshire: The Local History Group. OCLC 29636689.

- Lewis, F. R. (1938). "The History of Llanbadarn Fawr, Cardiganshire, in the Later Middle Ages". Transactions and archaeological record of the Cardiganshire Antiquarian Society. 12. OCLC 690106742.

- Lindley, P. (2003). John of Battle [de Bello; de la Bataile] (fl 1278; d 1300). doi:10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.T044991. ISBN 978-1-884446-05-4. Archived from the original on 9 April 2019. Retrieved 9 April 2019.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - Lloyd, T. H. (1977). The English Wool Trade in the Middle Ages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-52121-239-7.

- Maddison, J. (2012). Caernarfon Castle [Caernarvon]. doi:10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.T012957. ISBN 978-1-884446-05-4. Archived from the original on 9 April 2019. Retrieved 9 April 2019.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - Maddison, J. (2015). Walter of Hereford [de Ambresbury; Herford] (fl 1277; d 1309). doi:10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.T090569. ISBN 978-1-884446-05-4. Archived from the original on 9 April 2019. Retrieved 9 April 2019.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - Marks, R. (16 January 2006). Stained Glass in England During the Middle Ages. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-13496-750-6.

- Midmer, R. (1979). English Medieval Monasteries 1066 - 1540. London: Heineman. ISBN 978-0-43446-535-4.

- Morgan, P. (1987). War and Society in Medieval Cheshire, 1277–1403. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-71901-342-3.

- Palliser, D. M. (2004). "Royal Mausolea in the Long 14th Century, 1272–1422". In Ormorod W. M. (ed.). Fourteenth-Century England. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. pp. 1–15. ISBN 978-1-84383-046-7.

- Pevsner, N.; Hartwell, C.; Hyde, M.; Hubbard, E. (2012). Cheshire. The Buildings Of England. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-17043-6.

- Phillips, C. B.; Smith, J. H. (1994). Lancashire and Cheshire from AD1540. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-31787-167-5.

- Platt, C. (1994). Medieval England: A Social History and Archaeology from the Conquest to 1600 AD. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-41512-913-8.

- Powicke, F. M. (1991). The Thirteenth Century, 1216–1307 (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19285-249-6.

- Prestwich, M. (1988). Edward I. Yale English Monarchs. London: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-52006-266-5.

- Prestwich, M. (2003). The Three Edwards: War and State in England 1272–1377. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-13441-311-9.

- Prestwich, M. (2004). "Edward I (1239–1307)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/8517. ISBN 978-0-19-861412-8. Archived from the original on 11 June 2018. Retrieved 11 June 2018. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Ramsay, N. (2000). "Medieval Graffiti at Vale Royal Abbey, Cheshire". In Thacker, A. (ed.). Medieval archaeology, art and architecture at Chester. Leeds: British Archaeological Association. pp. 167–169. ISBN 978-1-902653-08-2.

- Ramsay, J. H. (1908). The Dawn of the Constitution: Or, the Reigns of Henry III and Edward I (A.D. 1216-137). London: Oxford University Press. OCLC 499117200.

- Robinson, David; Burton, Janet; Coldstream, Nicola; Coppack, Glyn; Fawcett, Richard (1998). The Cistercian Abbeys of Britain. London: Batsford. ISBN 978-0-71348-392-5.

- Stalley, R. A. (1999). Early Medieval Architecture. Oxford History of Art. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19284-223-7.

- Steane, J. (1993). The Archaeology of the Medieval English Monarchy. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-13464-159-8.

- Taylor, A. J. (1949). "The Cloister of Vale Royal Abbey". Journal of the Architectural, Archaeological, and Historic Society. new ser. 37: 295–297. OCLC 1009003046.

- Thompson, F. (1962). "Excavations at the Cistercian Abbey of Vale Royal, Cheshire, 1958". The Antiquaries Journal. 42 (2): 183–207. doi:10.1017/S0003581500018758. OCLC 759094243. S2CID 162194568.

- Turner, R. C; McNeil, R. (1988). "An Architectural and Topographical Survey of Vale Royal Abbey". Journal of the Chester Archaeological Society. 70: 51–79. doi:10.5284/1070303. OCLC 899973718.

- VCH (1980). "Houses of Cistercian Monks: The Abbey of Vale Royal". In Elrington, C. R.; Harris, B. E. (eds.). A History of the County of Chester. Victoria County History. Vol. 3. London: University of London & History of Parliament Trust. ISBN 978-0-19722-754-1.

- VRA (2019). "Vale Royal Abbey". Vale Royal Abbey Golf Club. Archived from the original on 14 April 2019. Retrieved 4 May 2019.

- Williams, D. H. (1976). White Monks in Gwent and the Border. Pontypool: Hughes and Son. ISBN 978-0-95004-906-9.

External links

- Information on the abbey from the Sheffield University site about Cistercian abbeys in the UK

- The Ledger Book of Vale Royal abbey: the main record book of the abbey. First published by the Record Society of Lancashire and Cheshire in 1914 – full-text version as part of British History Online

- Information about the stained glass from the Corpus Vitrearum Medii Aevi (CVMA) of Great Britain

- Religious organizations established in the 1270s

- Monasteries in Cheshire

- Cistercian monasteries in England

- Grade II* listed churches in Cheshire

- Christian monasteries established in the 13th century

- Edward Blore buildings

- Cholmondeley family

- John Douglas buildings

- Archaeological sites in Cheshire

- 1270 establishments in England

- 1538 disestablishments in England

- Abbots of Vale Royal Abbey

- Edward I of England

- Golf clubs and courses in Cheshire

- Buildings and structures in Cheshire

- Monasteries dissolved under the English Reformation