Folklore of Finland

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Finland |

|---|

|

| People |

| Languages |

| Mythology and folklore |

| Cuisine |

| Festivals |

| Religion |

| Literature |

| Music |

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Finnish. (March 2019) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

Folklore of Finland refers to traditional and folk practices, technologies, beliefs, knowledge, attitudes and habits in Finland. Finnish folk tradition includes in a broad sense all Finnish traditional folk culture. Folklore is not new, commercial or foreign contemporary culture, or the so-called "high culture". In particular, rural traditions have been considered in Finland as folklore.

According to a well-known essay by Alan Dundes folklore includes at least the folk stories and other verbal tradition, music, traditional objects and buildings, religion and beliefs, as well as culinary tradition.[1]

Variation

Finland is a country with a rich and varied folklore tradition. The country's long and complex history has led to the development of a wide range of folktales, legends, and beliefs, which vary considerably depending on where in Finland you are.[2][3]

One of the most striking differences in Finnish folklore is the contrast between the east and the west of the country.[4] The eastern part of Finland was historically under the influence of Russia, while the western part was under the influence of Sweden. This difference in cultural influence is reflected in the folklore of the two regions. Eastern Finnish folklore is often characterized by its Russian influences, such as the presence of tales about bogatyrs and other Russian folk heroes. Western Finnish folklore, on the other hand, is more closely related to the folklore of Sweden, with tales about trolls, elves, and other creatures from Scandinavian mythology.[5]

Another major difference in Finnish folklore is the contrast between the coast and the inland. The coastal regions of Finland have a long history of contact with other cultures, such as the Vikings and the Hanseatic League. This contact has led to the development of a rich and diverse folklore tradition, which includes tales about seafaring, trading, and other coastal activities. The inland regions of Finland, on the other hand, are more isolated and have a more traditional folklore tradition, which is often focused on farming, hunting, and fishing.[5]

Of course, these are just two of the many ways in which Finnish folklore varies depending on where you are in the country. There are many other factors that can contribute to the variation of Finnish folklore, such as the local geography, the climate, and the ethnic composition of the population. As a result, there is no single "Finnish" folklore tradition. Instead, there are many different regional traditions, each with its own unique character.[5]

Folk poetry

Folk poetry collection trips, starting from the 19th century, have resulted in the world's largest folk poetry archive, which is a card index of about 2.2 million cards. These collection trips were funded by the Finnish Literature Society.[6] It sponsored among other the ten trips by Elias Lönnrot. He edited the poems he and others had collected to national epos Kalevala and Kanteletar, and published collections of Finnish fairy tales and riddles.[7]

Notable figures

Joulupukki is a Finnish Christmas figure. The name "Joulupukki" literally means "Christmas goat" or "Yule Goat" in Finnish; the word pukki comes from the Teutonic root bock, which is a cognate of the English "buck", "Puck", and means "billy-goat". An old Scandinavian custom, the figure eventually became more or less conflated with Santa Claus.[8]

Foods

Finnish foods often use wholemeal products (rye, barley, oats) and berries (such as blueberries, lingonberries, cloudberries, and sea buckthorn). Milk and its derivatives like buttermilk are commonly used as food, drink or in various recipes. Various turnips were common in traditional cooking, but were replaced with the potato after its introduction in the 18th century.

Common examples of traditional Finnish foods include:

- Karjalanpiirakka (Karelian pies): These are small, round pies made from rye flour and filled with a variety of fillings, such as rice, potatoes, or berries.

- Leipäjuusto (bread cheese): This is a type of cheese made from rye flour and milk. It is often served with coffee or as a snack.

- Mämmi (black pudding): This is a traditional Finnish dessert made from rye flour, water, and sugar. It is typically served with milk or cream.

- Riisipuuro (rice porridge): This is a sweet porridge made from rice, milk, and sugar. It is often served with cinnamon and berries.

- Karjalanpaisti (Karelian stew): This is a hearty stew made from beef, pork, potatoes, and carrots. It is often served with lingonberry jam.

- Herkkutarjotin (appetizer platter): This is a platter of traditional Finnish appetizers, such as smoked salmon, pickled herring, and cheese.

- Kalakeitto (fish soup): This is a hearty soup made from fish, potatoes, and vegetables. It is often served with rye bread.

- Mustamakkara (black sausage): This is a type of sausage made from pork, blood, and rye flour. It is often served with mustard and lingonberry jam.

- Lihapullat (meatballs): These are Swedish-style meatballs made from ground beef, pork, and breadcrumbs. They are often served with gravy and potatoes.

- Pannukakku (pancake): This is a thin pancake made from flour, milk, eggs, and sugar. It is often served with jam, syrup, or fruit.

Folk dance

Some examples of traditional dances practiced throughout the country include.

- Humppa: This is a lively dance that is often danced in a circle.

- Jenkka: This is a fast-paced dance that is often danced in a line.

- Letkajenkka: This is a fun and energetic dance that is often danced in a group.

- Polska: This is a traditional dance that is often danced in a pair.

- Säkkijärven polkka: This is a popular dance that is often danced in a pair.

Tradition

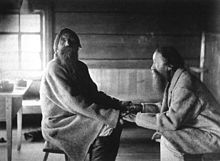

Living sauna culture still includes many ancient traditions.[9] Tradition of communal work, talkoo is also living strong. Oral tradition has been passed from generation to generation. It includes fairy tales, folk wisdom, proverbs and poetry. Poetry in Kalevala metre has been easy to remember because of its rolling metre, repeating sections and alliteration.[10]

Sauna

Finnish saunas are an important aspect of Finnish culture and have been a significant part of their lifestyle for centuries. In Finland, saunas are not just a place to bathe but are considered to be a place for physical and spiritual purification, relaxation, and socialization.[11][12]

The traditional Finnish sauna is a wooden structure, usually made of logs, and is a separate building or room within a larger building. The sauna room is typically heated by a wood-burning stove or an electric heater, and the heat is generated by pouring water over heated rocks. This creates steam and humidity. The temperature inside a traditional Finnish sauna can reach up to 80-100 °C.[13]

References

- ^ "What is folklore". University Library of University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Retrieved 17 October 2015.

- ^ Pentikäinen, Juha (1999). Kalevala mythology. Ritva Poom. Bloomington [Ind.]: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-33661-9. OCLC 41445812.

- ^ Dresden, M. J.; Maranda, Elli Köngäs; Maranda, Elli Kongas (1969). "Finnish Folklore Reader and Glossary". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 89 (4): 830. doi:10.2307/597013. ISSN 0003-0279. JSTOR 597013.

- ^ Oinas, Felix J. (1985). Studies in Finnic folklore : homage to the Kalevala. [Helsinki]: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura. ISBN 951-717-315-6. OCLC 12482663.

- ^ a b c Rausmaa, Pirkko-Liisa (2013). An anthology of Finnish folktales. Cardiff. ISBN 978-1-86057-083-4. OCLC 811000549.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Keisari lahjoitti tontin Suomen kielen talolle" (in Finnish). Helsingin Sanomat. Archived from the original on 9 October 2015. Retrieved 17 October 2015.

- ^ "Lönnrot, Elias (1802 - 1884)" (in Finnish). Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura. Retrieved 17 October 2015.

- ^ "How did Finland get Santa Claus ?". almondella (in Finnish). Retrieved 17 October 2015.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Bare facts of the Sauna". This is Finland. Retrieved 17 October 2015.

- ^ "Kalevalamitta" (in Finnish). Kalevalaseura. Retrieved 17 October 2015.

- ^ Lockwood, Yvonne R. (1977). "The Sauna: An Expression of Finnish-American Identity". Western Folklore. 36 (1): 71–84. doi:10.2307/1498215. ISSN 0043-373X. JSTOR 1498215.

- ^ Keast, Marja Leena; Adamo, Kristi B. (2000). "The Finnish Sauna Bath and Its Use in Patients With Cardiovascular Disease". Journal of Cardiopulmonary Rehabilitation and Prevention. 20 (4): 225. ISSN 1932-7501. PMID 10955262.

- ^ Nordskog, Michael (2010). The opposite of cold : the Northwoods Finnish sauna tradition. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-0-8166-5682-0. OCLC 613311403.