Savaiʻi

Nickname: Soul of Samoa | |

|---|---|

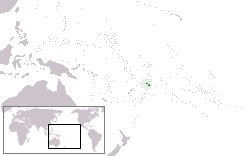

Map of Savaiʻi | |

| |

| Geography | |

| Location | Pacific Ocean |

| Coordinates | 13°35′S 172°25′W / 13.583°S 172.417°W |

| Archipelago | Samoa Islands |

| Area | 1,694 km2 (654 sq mi) |

| Length | 70 km (43 mi) |

| Width | 46 km (28.6 mi) |

| Highest elevation | 1,858 m (6096 ft) |

| Highest point | Mt Silisili |

| Administration | |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 43,958[1] (2016) |

| Pop. density | 25/km2 (65/sq mi) |

| Ethnic groups | 92.6% Samoans, 7% Euronesians, 0.4% Europeans |

| Additional information | |

| Last eruption by Mt Matavanu (1905–1911) | |

Savaiʻi is the largest and highest island both in Samoa and in the Samoan Islands chain. The island is also the sixth largest in Polynesia, behind the three main islands of New Zealand and the Hawaiian Islands of Hawaii and Maui. Though it’s larger than the country’s second main island Upolu it’s by far not as populous.

Samoans sometimes refer to the island of Savaiʻi as Salafai: This is its classical Samoan name, and is used in formal oratory and prose. The island is home to 43,958 people (2016 census), and they make up 24% of the population of Samoa.[1] The island’s only township and ferry terminal is called Salelologa. It is the main point of entry to the island, and is situated at the east end of Savaiʻi. A tar sealed road serves as the single main highway, connecting most of the villages. Local bus routes also operate, reaching most settlements.

Savaiʻi is made up of six itūmālō (political districts). Each district is made up of villages that have strong traditional ties with each other — of kinship, history, and land — and that use similar matai (titles for their village chiefs). Savaiʻi’s relatively limited ecotourism operations are organized mostly at the village level. The Mau, Samoa's non-violent movement for political independence during colonialism in the early 1900s, had its beginnings on Savaiʻi, with the Mau a Pule movement.[2]

The island is the largest shield volcano in the South Pacific. Its most recent eruptions were in the early 1900s. Its central region comprises the Central Savaiʻi Rainforest, extending over 72,699 hectares (727 km2), which is the largest contiguous rainforest in Polynesia. It is dotted with more than 100 volcanic craters and contains most of Samoa's native species of flora and fauna, making it one of the world’s most globally significant conservation areas.[3]

Society and culture

Faʻa Sāmoa, the unique traditional culture and way of life in Samoan society, remains strong in Savaiʻi, where there are fewer signs of modern life and less development than on the island of Upolu, where the capital, Apia, is located.

Samoan society is communal and based on extended family relationships and socio-cultural obligations, so that kinship and genealogies are important. These faʻa Sāmoa values are also associated with concepts of love (alofa), service (tautua) to family and community, respect (faʻaaloalo) and discipline (usitaʻi).[4] Most families are made up of a number of different households situated close to each other.

Like the rest of Samoa, Savaiʻi is made up of villages with most of the land collectively owned by families or ʻaiga. Most people on Savaiʻi, 93% of the island population, live on customary land.[1] The heads of the family are called matai, the holders of family names and titles. An extended family can have a number of chiefs with different chief titles. Men and women in Samoa have equal rights to chief titles which are bestowed by consensus of the extended family. Traditionally, male and female roles are defined by labours and tasks, chiefly status and age. Women play an important role contributing to family decisions as well as village governance.[5] Elders are revered and respected. Social relationships are dictated by cultural etiquettes of politeness and common greetings.

The Samoan language has a 'polite' and formal variant used in Samoan oratory and ceremony as well as in communication with elders, guests, people of rank and strangers. In all villages, the majority of people are largely sustained by plantation work and fishing[6] with financial assistance from relatives working in Apia or overseas. Most people live in coastal villages although there are some settlements inland such as the villages of Aopo, Patamea and Sili.

Behind the villages are cultivated plantations with crops of taro, cocoa koko, coconuts popo, yams palai, ʻava, fruit and vegetables as well other native plants such as pandanus for weaving ʻie tōga fine mats and bark for tapa cloth.

There is a church in every village, mostly Christian denominations.[7] Sunday is sacred and a day of rest as 98% of Samoans identify themselves as religious. White Sunday is one of the most important days of the year in Samoa when children are treated with special attention by their families and community.

Politics

With the country's independence in 1962, Samoa incorporates both traditional political structures alongside a western parliamentary system. The modern national Government of Samoa, based in the capital Apia with the roles of Prime Minister, Members of Parliament and western styled political structure, is referred to as the Malo. Only Samoans with chief matai titles are eligible to become Members of Parliament.

Alongside Samoa's national and modern political structure is traditional authority vested in family chiefs (matai). The term Pule is applied to traditional authority in Savaiʻi.

The word Pule refers to appointments or authorities conferred on certain clans or individuals, sometime in the political history of Samoa. This traditional Pule authority was centred in certain villages around Savaiʻi. In the early 20th century, these Pule areas on Savaiʻi island were Safotulafai, Saleaula, Safotu, Asau, Satupaʻitea and Palauli.[8] Safotu, Asau, Satupaʻitea and Vailoa (Palauli district) gained 'Pule' status at different times in the 19th Century, and together with the two older Pule districts, Safotulafai and Saleaula, became the six Pule centres on Savaiʻi.[9]

In 1908, the 'Mau a Pule' resistance movement to colonial rule, which grew to become the national Mau movement, began on Savaiʻi and represented traditional authority against the German administration of Samoa. The equivalent term 'Tumua' is associated with traditional authority on Upolu island.

At the local level throughout Samoa, traditional authority is vested in a chiefs' council (fono o matai) in each village. The fono o matai carry out 'village law' and socio-political governance based on their traditional authority and faʻa Samoa. The authority of the matai is balanced against central government, the Malo. Most of the matai are males, however, the women in each village also have a voice in domestic affairs through the women's committees.

The main government administration offices of the Malo on Savaiʻi are situated in the village of Tuasivi, 10 minutes north of the ferry terminal and market at Salelologa. There's a district hospital, police station, post office and court houses in Tuasivi.

Vaʻai Kolone, a matai and businessman from Vaisala, at the west end of the island, became the Prime Minister of Samoa twice in the 1980s.

Samoa has 11 political districts (itūmālō) and 6 are in Savaiʻi; Faʻasaleleaga, Gagaʻemauga, Gagaʻifomauga, Palauli, Satupaʻitea and Vaisigano.

Scenery and landscape

Savaiʻi is mountainous, fertile and surrounded by coral reefs.[10] Lonely Planet describes the Savaiʻi landscape as 'spectacular tropical terrain'.[11] The island has a gently sloping profile, reaching a maximum altitude of 1,858 metres at Mt Silisili, the highest peak in the country and the Samoa Islands chain. Volcanic craters in the highlands are strung across the central ridges from Tuasivi (literally, backbone) village in the east towards Cape Mulinuʻu to the west.[12] The lava fields at Saleaula village on the central north coast[13] are the result of volcanic eruptions from Mt Matavanu (1905–1911). Most of the coastline are palm fringed beaches and there are rainforests, waterfalls, caves, freshwater pools, blowholes and coral reefs. There are also numerous archaeological sites, including star mounds, fortifications and pyramids such as the Pulemelei Mound in Palauli district. Archaeology in Samoa has uncovered many pre-historic settlements including sites at Vailoa and Sapapaliʻi.

Myths and legends

Rich in Polynesian history and oral tradition, Savaiʻi is mentioned in myths and legends across the Pacific Islands and has been called the "Cradle of Polynesia."[14]

Samoan mythology tells stories of different gods. There were gods of the forest, the seas, rain, harvest, villages, and war.[15] There were two types of gods: atua, who had non-human origins, and aitu, who were of human origin. Tagaloa was a supreme god who made the islands and the people. Mafuiʻe was the god of earthquakes. There were also a number of war gods. Nafanua, Samoa's warrior goddess, hails from the village of Falealupo at the west end of the island, which is also the site of the entry into Pulotu, the spirit world. Nafanua's father Saveasiʻuleo was the god of Pulotu.[16] Another well-known legend tells of two sisters, Tilafaiga and Taema, bringing the art of tattooing to Samoa from Fiti. Tilafaiga is the mother of Nafanua. The freshwater pool Mata o le Alelo 'Eyes of the Demon' from the Polynesian legend Sina and the Eel is situated in the village of Matavai on the north coast in the village district of Safune.[17] Another figure of legend is Tui Fiti, who resides at Fagamalo village in the village district of Matautu on the central north coast. The village of Falelima is associated with a dreaded spirit deity called Nifoloa.

Savaiʻi is known as the "Soul of Samoa." "Here the 20th century has put down the shallowest roots, and the faʻa Samoa—the Samoan way—has the most meaning."[18]

Flora and fauna

Flora

The tropical climate and fertile soil results in a variety of flora. Vegetation types include littoral, wetland and volcanic vegetation. Rainforests include coastal, lowland and montane forests (above 500m elevation). Cloud forests are located in the highest elevations of the island which are often under cloud cover with wet conditions. At Mt Silisili, cloud forest occurs above 1200 m elevation. The Savaiʻi forest is dominated by a 15 to 20 m high canopy of Dysoxylum huntii, Omalanthus acuminatus, Reynoldsia pleiosperma and Pterophylla samoensis. Other common trees include Coprosma savaiiense, Psychotria xanthochlora, Spiraeanthemum samoense and Streblus anthropophagorum.[19] There are nearly 500 species of flowering plants and about 200 species of ferns in Samoa, making it richer than that of any tropical Polynesian island other than those in the Hawaiian archipelago.[20] About 25% of the species are endemic to Samoa.[21]

The variety of tropical plant life is also a material source for floral adornment, tapa cloth, ʻie toga, perfumes, coconut oil as well as herbs and plants for traditional medicines.[22] Common plants with everyday usage include the smooth reddish purple leaves of the ti (Dracaena terminalis) plant used with coconut oil for traditional massage, fofo, and the dried root stems of Piper methysticum (Latin "pepper" and Latinized Greek "intoxicating") are mixed with water for the important ʻava ceremony conducted during cultural events and gatherings.

Fauna

Animal species include fruit bats such as the Samoa flying-fox (Pteropus samoensis), land and seabirds, skinks and geckos. The birdlife of Samoa includes a total of 82 species, of which 11 are endemic, found only in Samoa. Endemic birdlife found only on Savaiʻi include species such as the Samoan white-eye (Zosterops samoensis) which is only found in the high cloud forests and alpine scrub around Mt Silisili, and Samoan moorhen (Gallinula pacifica), which was last recorded in 1873 near Aopo with possible sightings in 1984 and 2003.[23] The tooth-billed pigeon, (Didunculus strigirostris), also known as the manumea is also endemic and now increasingly rare, leading to the current proposition to upgrade it to critically endangered. It is the national bird of Samoa and is found on some of the local currency. It is likely that the extensive loss of lowland forest, hunting and invasive species are responsible for the decline of this stunning species.

Samoa has more native species of ferns and butterflies than New Zealand, a country 85 times larger.[24] In 2006, research samples of the blue moon butterfly species (Hypolimnas bolina) on Savaiʻi found that males accounted for just 1% of the population and had almost been wiped out by an invasive species. Sampling a year later showed a dramatic comeback and recovery to 40%.[25]

The surrounding Pacific Ocean, coral reefs and lagoons are rich in marine life and some are harvested as an important source of food in an economy that is mainly subsistence with locals reliant on the land and the ocean for survival. Dolphins, whales and porpoises migrate through Samoa's waters.[26] The Palolo reef worm (Eunice viridis) is a Samoan cuisine delicacy which appear in the ocean only one day of the year. Palolo has cultural significance and entire villages flock to the sea for harvest.

Surrounded by a variety of tropical fauna, Samoan mythology is rich with stories of animals incorporated into their culture, traditional beliefs and way of life.

Conservation

The island is rich in biodiversity and endemic native species which are also highly threatened. The Central Savaiʻi Rainforest comprising 72,699 hectares is the largest continuous patch of rainforest in Polynesia and contains most of Samoa's native species.[3] Seventy percent of Samoa's settlements are by the coast with increasing threat from climate change and sea level rising. As most of the land in Samoa is under customary ownership, conservation projects are developed with the approval and cooperation of villages. The Government of Samoa supports conservation covenants for three natural areas on Savaiʻi, the Falealupo Rainforest Preserve, Tafua Rainforest Preserve and Aopo Cloud Forest Reserve. The conservation projects are a partnership between the local matai and villages, government, conservation organisations and international funding[27] such as the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). These support community based projects in villages, many of which are developed with international support and micro financing in areas of sustainable livelihoods, land management and conservation on both land and in coastal marine areas. There are wetlands in the village of Satoʻalepai on the central north coast where large sea green turtles (Chelonia mydas) are kept by the locals as an eco-tourism experience for visitors and provide extra income for communities. Another turtle habitat is at the village of Auala on the north west coast.

Travel information

Ferry terminal

Salelologa is the main port and township, situated at the east end of the island where the inter-island ferry terminal is located. A regular passenger and vehicle ferry operates seven days a week in the Apolima Strait between Salelologa and Mulifanua wharf on Upolu. The ferry crossing takes about 90-minutes with views of Apolima and Manono islands to the south. The ferries operate only during the day. Local buses and taxis are available at the terminal and township. There's also a wharf at Asau at the north west end of the island, sometimes used for yachting.

Driving

Savaiʻi has an excellent tar-seal road circling the island. A leisurely drive around the island takes under 3 hours. The scenic drive is mostly along the coastline where most of the locals live in villages. Driving in Samoa is on the left side of the road, effective from 7 September 2009 when the government changed the law to bring motoring in line with neighbouring countries. Samoa is the first country in the 21st century to switch to driving on the left.[28]

Airport

Maota Airport is a small airstrip with basic facilities situated 10-minutes south of Salelologa ferry terminal and township. Flights operate between Maota and Asau airstrip and Faleolo International Airport on Upolu. The inter-island flights take about 30-minutes.[29] Asau Airport is an airstrip at the north west end of the island which mainly services chartered flights.[30]

Amenities

A local market (open Monday – Saturday) at Salelologa sells fresh produce of fruit, vegetables and local crafts. There are also clothing stores, several small supermarkets, a wholesaler, petrol stations, bakeries, budget hotels and accommodation,[31] buses, taxis, rental car companies as well as public amenities such as internet access, banks and Western Union money transfer outlets. There are small local shops in every village around Savaiʻi, selling basic groceries. Markets and most shops in Samoa close on Sundays with smaller outlets opening late afternoon after church services.

Hospitals

The main hospital on Savaiʻi is the Malietoa Tanumafili II Hospital, situated in Tuasivi village.[32] Another district hospital is in Safotu, on the central north coast.

Eco-tourism

Cultural context

With most of the land in Samoa under customary ownership with local governance by matai, tourism experiences take place on village land and within local culture. There are hotels, but like the rest of Samoa, many villages provide beach fale accommodation for visitors all around the island such as Manase on the central north coast.[33] These are small local businesses run by families within their villages and most of the income goes directly back to the community. There are island tours, diving, fishing, plantation trips, treks and other tourism related activities. Most shops are closed on Sundays with a few re-opening after church services in late afternoon. Every day, evening prayer (sa) takes place in every village around dusk before the evening meal and lasts about half an hour. It is usually signalled by the sound of a conch shell or the ringing of the church bell. The sa usually means no loud noise or walking through the village commons. Matai sometimes stand by the side of the main road, which pass through village land, to slow down traffic until prayers are over. Tourism is overseen by the government Samoa Visitors' Bureau, situated in the capital Apia, which can also help to settle disputes. At the village level, much of the country's civil and criminal matters can be dealt with directly by the matai chief village councils.

The last sunset in the world

The village of Falealupo on the westernmost point of Savaiʻi, is just 20 miles (32 km) from the dateline. It was arguably the last place in the world to see the sunset until a time zone change at end of 2011.[34] Falealupo was the site of Millennium 2000 celebrations and reported by the BBC as 'the last place on earth to enter the new millennium.'[35] Falealupo also has protected rainforests.

Surfing

Savaiʻi has surfing off reef breaks all around the island, with more waves during summer on the north coast and the south coast in winter.[36] The conditions are not for novice surfers and there can be dangerous undercurrents and rips. Satuiatua Beach Fales[37] on the south-west coast is owned by locals and was one of the first tourism accommodations attracting surfers. Other surfing spots around Savaiʻi include breaks off the villages of Lano, Aganoa Beach by Tafua, Lefagaoaliʻi, Lelepa and Fagamalo.

Tourism development

In 2008, an American company South Pacific Development Group (SPDG) obtained a 120-year lease for 600 acres (2.4 km2) of prime oceanfront customary land in Sasina, to build a luxury resort estimated to cost $450 – US$500 million. The developers pay less than one penny per square foot of land per month. The development will include a casino, timeshares and a cultural centre. The company is expecting to receive the casino licence for Savaiʻi island in a new law legalising casinos proposed by the government,[38] the Casino and Gambling Bill 2010 tabled to parliament by the prime minister Tuilaepa Aiono Sailele Malielegaoi in March 2010.[39]

The announcement of the tourist development raised concern among environmental group O Le Siʻosiʻomaga Society about the impact of the development.[40] The Samoa Hotel Association also expressed concern at the size of the development and its impact on the island's environment and infrastructure.[41] The development is supported by the Government of Samoa. The lease is unprecedented in Samoa where 80% of the land is under customary ownership, 6% freehold and the rest owned by the government.[42]

Film

Moana (1926), one of the earliest documentaries made in the world, was filmed in Safune on the central north coast. The film was directed by Robert J. Flaherty who lived with his wife and children in Safune for more than a year. A cave with a pool in Safune was converted into a film processing laboratory and two young men from the village were trained to work there. Flaherty cast people from Safune in the film including local boy Taʻavale who played the lead role of 'Moana'. Another boy called Peʻa played the role of Moana's younger brother. Peʻa later became a chief with the title Taulealeausumai from the village of Faletagaloa. Playing the lead female role in the film was Faʻagase, a girl from Lefagaoaliʻi. The film also showed the young hero 'Moana' receiving a peʻa, a traditional Samoan tattoo.

Geography

Savaiʻi island lies north west of Upolu. These two largest islands of Samoa are separated by the Apolima Strait which is about 8 miles (13 km) wide with the small inhabited islands of Manono and Apolima between them. Savaiʻi island is of volcanic origin and the mountainous interiors are covered with dense rain forests. The surrounding landscape consists of fertile plateaux and coastal plains with numerous rivers and streams.

Climate

The climate is oceanic tropical with high temperatures and humidity. The heaviest rainfall occurs between the months of November and April, and cyclones, which are relatively frequent, are most likely to occur during these same months.[19] Two cyclones, Cyclone Ofa (1990) and Cyclone Valerie (1991)[43] caused extensive damage on the north and west coast of Savaiʻi.

Geology

Savaiʻi is the largest shield volcano in the South Pacific[44] and only 3% is above water.[45] It is an active volcano, which last erupted in 1905–1911 with lava flows that destroyed villages on the central north coast. The island is formed by a massive basaltic shield volcano which rises from the seafloor of the western Pacific Ocean. A possible model for the formation of the volcanic Samoa island chain is explained by the Samoa hotspot situated at the east end of the Samoa Islands. In theory, the Samoa hotspot is a result of the Pacific Tectonic Plate moving over a 'fixed' deep and narrow mantle plume spewing up through the Earth's crust. The Samoa islands generally lie in a straight line, east to west, in the same direction the Plate is moving. In the classic hotspot model, primarily based on studies of the Hawaii hotspot, the volcanic islands and seamounts further away from the Samoa hotspot should be progressively older. However, Savaiʻi, the most western of the Samoa island chain, and Taʻu Island, the most eastern of the Samoa islands, both erupted in the 20th century, data which is an enigma for scientists.[46] Taʻu last erupted in 1866. Another discrepancy in the data from the Samoa islands is that subaerial rock samples from Savaiʻi were too young by several million years to fit the classic hotspot model of age progression in an island chain, raising arguments among scientists that the Samoa islands does not have a plume origin. The nearness of Savaiʻi and the Samoa island chain to the Tonga Trench at the south became a possible explanation for these discrepancies as well as the possibility that the islands were formed by magma seeping through cracks in stressed fracture zones.[45] However, in 2005, an international team gathered further submarine samples from the deep flanks and rifts of Savaiʻi. Tests on these later samples showed much older ages, about five million years old, that fit the hotspot model.[47] The discovery in 1975 of Vailuluʻu Seamount 45 km east of Taʻu in American Samoa has since been studied by an international team of scientists and contribute towards understanding of the Earth's fundamental processes.[48]

Pre-historic geological formations on SavaiʻI have created natural sites such as the Alofaʻaga Blowholes and Moso's Footprint. The Peʻapeʻa Cave, named after the swallows that inhabit it, is a lava tube one kilometre in length, formed during the Mt Matavanu eruptions.[13]

Volcanic activity

The island consists of a large shield volcano similar in form to the Hawaiian volcanoes. Savaiʻi remains volcanically active, with recent eruptions from Matavanu between 1905 and 1911. The Matavanu eruptions flowed towards the central north coast and destroyed villages including Saleaula. Other recent volcanic eruptions include Mata o le Afi in 1902 and Mauga Afi in 1725. The lava field at Saleaula are extensive enough to be visible in high altitude photographs.[49]

Education

Samoa education system

Like the rest of the country, the education system on Savaiʻi is mostly public education covering primary and secondary schooling in villages. Education in Samoa is compulsory for children aged 5-years to 14-years or until the completion of Year 8.

- Primary education – Year 1 – 8 (8-years)

- Secondary education – Year 9 – 13 (5-years)

Entrance to secondary education is determined by a National Examinination at Year 8. Top achievers in government schools can enter Samoa College on Upolu island with the next group offered places at Vaipouli College in Gagaʻemauga district on the island's central north coast. The rest attend the nearest secondary school in their district. With most of the land in the country under customary ownership in village settlements, schooling and education is a joint responsibility between the government and villages, governed at the local level by matai.

Cost

Village responsibility

In both primary and secondary schools across Samoa, villages are responsible for school buildings, equipment, furniture, fundraising and collection of school fees.[50] With most of the population living off their land in a mostly traditional way of life with little paid employment available, villages such as Falealupo were forced to sell logging rights to their native forests in 1990, to pay for their school buildings, following threat of closure from the government. An American ethnobotanist, Paul Cox, who had lived in the village with his family, raised funds internationally to save the school and create a conservation covenant with matai to protect their native forest.[51]

Government responsibility

The government is responsible for teachers, curriculum and educational materials as well as assessments and exams administered under the Ministry of Education, Sports and Culture.[52] The government also employs School Review Officers who are the main liaison with schools.

International aid

The government receives international aid for education from countries such as New Zealand, Australia and Japan through their foreign aid programmes. In 2006, a bilateral partnership between Ausaid (Australia) and NZAID (New Zealand) with the Asia Development Bank launched an education sector program (ESPII) focusing on primary and secondary education over a number of years. The contribution from AUSaid is up to $14 million[53] dollars with NZAID committing NZ$12.5 million over five years.[54] Australia is also contributing $2 million towards a School Fee Grant Scheme to 163 primary schools during 2009–2010.[53] Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) also constributes significant aid towards education.[55]

Tertiary education

Most opportunities for tertiary education in the country are available on Upolu island, the location of the National University of Samoa and the Alafua Campus of the regional University of the South Pacific. International volunteer programmes including the American Peace Corps also provide teachers throughout schools in Savaiʻi and the rest of the country.

School calendar

| School Terms | Dates | Duration |

|---|---|---|

| Term 1 | 1 February – 15 May | (15 weeks) |

| Term 2 | 7 June – 3 September | (13 weeks) |

| Term 3 | 20 September – 10 December | (12 weeks) |

| School holidays | 2010 dates |

|---|---|

| 15 May – 6 June | |

| 5–19 September | |

| 11 December – 30 January |

List of schools in Savaiʻi

There are 9 secondary schools and 48 primary schools on the island.[56]

Public library

Savaiʻi Public Library is the only public library on the island. It is situated by the old market in the township of Salelologa at the east end of Savaiʻi. The library is a branch of the central Samoa Public Library in the capital Apia on Upolu island.[57]

Public holidays

Public holidays;[50]

| Holiday | Date |

|---|---|

| Good Friday | Varies |

| Easter Monday | Varies |

| Mother's Day | 10 May |

| Samoa Independence Day | 1 June (celebrations) |

| Father's Day | 9 August |

| White Sunday (2nd Sunday of October) | Varies |

| Christmas Day | 25 December |

| Boxing Day | 26 December |

Samoa gained political independence from New Zealand on 1 January 1962. However, independence celebrations take place on 1 June, each year.[58]

Historical

Notable places & people

- Archaeology in Samoa has uncovered prehistoric settlements inland in many parts of the island including sites at Sapapaliʻi village and Vailoa in Palauli district.

- The exiled orator Lauaki Namulauulu Mamoe (died 1915), leader of the Mau a Pule, a resistance group against colonial rule in the early 1900s, was from the traditional sub-district of Safotulafai.

- The missionary John Williams (1796–1839) arrived in the village of Sapapaliʻi in 1830. Sapapaliʻi was also a base for the Malietoa title on Savaiʻi. A plaque by the main road in the village commemorates Williams' landing.

- In pre-history, the village of Safotu was a settlement for Tongans.

- Olaf Frederick Nelson, another exiled leader of the Mau movement in the 1920s, was born in Safune.

- The Pulemelei Mound in Palauli is the largest and most ancient structure in Polynesia.

- Pio Taofinuʻu (1923–2006), the first Polynesian cardinal and bishop, was from the village of Falealupo, Savaiʻi.

- Reverend George Pratt (1817–1894), a missionary of the London Missionary Society during the 1800s, lived in Matautu on the north coast. Pratt authored the first Samoan English language dictionary A Grammar and Dictionary of the Samoan Language, with English and Samoan Vocabulary, first printed in 1862.[59] Pratt's valuable dictionary records many old words of special interest–specialist terminology, archaic words and names in Samoan tradition. It contains sections on Samoan poetry and proverbs, and an extensive grammatical sketch.[60]

- Activist Leilua Lino is from Asau on the island. In 2019 she was presented with a Commonwealth Innovation for Sustainable Development Award by Prince Harry.[61][62]

World War II

During World War II, Savaiʻi came under the Allies 'Samoa Defense Group' which included Upolu, Tutuila and Wallis Island and later extended in 1944 to cover bases in other islands such as Bora Bora and the Cook Islands. A military governor of the Samoa Defense Group was Brigadier General Henry L. Larsen who had secret orders mandating a defensive position of the islands from east to west. The code name for the entire group of islands was 'Straw' and the code name for Savaiʻi was 'Strawman.' The code for Upolu was 'Strawhat,' Tutuila 'Strawstack' while Wallis Island was 'Strawboard.' A small base was set up on the central north coast village of Fagamalo, which had a wharf and anchorage. Fagamalo was the main village for the colonial administration at the time on Savaiʻi, situated where the small post office is today.

In its present unprotected state, Western Samoa is a hazard of first magnitude for the defense of American Samoa. The conclusion is inescapable that if we don't occupy it the Japanese will and there may not be a great deal of time left.

8 February 1943 Report on Western Samoa defence by 2nd Marine Brigade's intelligence officer, Lieutenant Colonel William L. Bales.[63]

On 18 May 1942 the 3rd Marine Brigade with 4,853 officers and men were on Upolu and Savaiʻi under the command of Brigadier General Charles D. Barrett.

1839 Wilkes Expedition

In October 1839, Savaiʻi and the Samoa Islands were surveyed by the famous United States Exploring Expedition led by Charles Wilkes. The survey of Savaiʻi was performed by Lieutenant-Commandant Ringgold aboard the U.S. Brig Porpoise. Wilkes and other ships in the expedition were surveying Upolu and Tutuila at the same time. The Porpoise first touched down at the village of Sapapaliʻi. Some of the team, Dr Pickering and Lieutenant Maury were dropped off while the brig surveyed the island's coastline and tides. Dr Pickering and the lieutenant were hosted by the resident missionary at Sapapaliʻi, the Reverend Mr. Hardie. The Porpoise examined the bay of Palauli where there was a missionary station under the supervision of a Mr M'Donald. Wilkes' report also described Saleaula village, Asau at the west end of the island and 'the beautiful village of Falealupo' which was under the charge of a Tongan missionary. At the 'north point' of the island, the brig found 'good anchorage' in the bay of Matautu (where the village of Fagamalo is situated). The brig was anchored and the harbour surveyed. Wilkes' wrote that this was the harbour on the island where a vessel could anchor in safety. Here, in Matautu, the explorers noticed a difference with other parts of Savaiʻi.

A great difference in form, physiognomy and manners...was observed here, as well as a change in the character of many articles of manufacture. The warclubs and spears were of uncommon form, and neatly made.

On 24 October, Wilkes writes, that the Porpoise arrived back at Sapapaliʻi village, having been gone nine days. The team met paramount chief Malietoa and his son at the village. With local guides Dr Pickering had travelled some way into the interior of the island, reaching one side of a volcanic crater about one thousand feet above the sea and some seven miles (11 km) inland.[64]

One 10 November 1839, the Wilkes Expedition weighed anchor at Apia and sailed westward, and on 11 November, had lost sight of Savaiʻi.

Gallery

-

Savaiʻi island from space (NASA photo)

-

Historic church in Safotu village.

-

View from Pulemelei Mound

-

Mu Pagoa Waterfall in Palauli district.

-

Stone church in Satupaʻitea on Savaiʻi c. 1908

-

Local bus

-

Lava fields on Savaiʻi

-

Sunset at Sapapaliʻi

-

Samoa fire dance siva afi

-

Beach fale, popular in eco-tourism in villages around the coast.

-

Fishing canoe (vaʻa) with small outrigger

-

View from the ferry with tiny Apolima island and Savaiʻi coast (right).

-

Mount Matavanu volcano, 1906

-

Breadfruit tree (Artocarpus altilis), a staple food in Samoa.

-

Roast coacoa koko beans grown locally for hot Samoan koko drink.

See also

- Archaeology in Samoa for archaeology on Savaiʻi

- Architecture of Samoa

- Districts of Samoa (political districts)

- Culture of Samoa

- Samoa Islands

- Samoan language

- Samoa Tourism Authority

References

- ^ a b c "Final Population and Housing Census 2006". Samoa Bureau of Statistics. July 2008. Archived from the original on 1 January 2011.

- ^ Meleisea, Malama; Meleisea, Penelope Schoeffel (1987). Lagaga A Short History of Western Samoa. editorips@usp.ac.fj. p. 117. ISBN 978-982-02-0029-6. Retrieved 26 July 2014.

- ^ a b "Priority Sites for Con-servation in Samoa: Key Biodiversity Areas" (PDF).

- ^ 3. Culture and identity – Samoans – Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand Faʻa Sāmoa, Samoan culture, New Zealand Encyclopaedia Archived 2 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Ember, Carol R.; Ember, Melvin (2003). Encyclopedia of Sex and Gender Men and Women in the World's Cultures Topics and Cultures A-K – Volume 1; Cultures L-Z -. Springer. p. 802. ISBN 978-0-306-47770-6. Retrieved 26 July 2014.

- ^ "Gagaemauga 3 District: Community-based Adaptation for Gagaemauga 3 District | Adaptation Learning Mechanism". adaptationlearning.net. Archived from the original on 7 January 2011.

- ^ CHAPTER V — A Samoan Village | NZETC An Introduction to Samoan Custom by F.J.H. Grattan, Chapter V, A Samoan Village, p. 53 Archived 23 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Tumua and Pule. — Construction and significance in the Political history of Samoa | NZETC An Account of Samoan History up to 1918 by Teʻo Tuvale, NZ Licence CC-BY-SA 3.0, NZ Electronic Text Centre. Retrieved 31 October 2009 Archived 30 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Soʻo, Asofou (2008). Democracy and Custom in Sāmoa An Uneasy Alliance. editorips@usp.ac.fj. p. 75. ISBN 978-982-02-0390-7. Retrieved 26 July 2014.

- ^ "Samoa." The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition. 2008. Encyclopedia.com. 3 Oct. 2009 [1]

- ^ "Introducing Savai'i". www.lonelyplanet.com. Archived from the original on 13 April 2014.

- ^ "Savaiʻi | island, Samoa". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 13 October 2013.

- ^ a b "Where the wild things blow". The Sydney Morning Herald. 28 June 2009. Archived from the original on 4 November 2012.

- ^ "Samoa: History". www.pacificislandtravel.com. Archived from the original on 18 February 2012.

- ^ Culbertson, Philip; Agee, Margaret Nelson; Makasiale, Cabrini ʻOfa (2007). Penina Uliuli Contemporary Challenges in Mental Health for Pacific Peoples. University of Hawaii Press. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-8248-3224-7. Retrieved 26 July 2014.

- ^ Turner, George (2006). Samoa, a Hundred Years Ago and Long Before. Echo Library. p. 123. ISBN 978-1-4068-3371-3. Retrieved 26 July 2014.

- ^ "Living Heritage -Marcellin College – Sina and the Eel". livingheritage.org.nz. Archived from the original on 29 October 2012.

- ^ Robert Booth, "The two Samoas still coming of age," in National Geographic Magazine, Vol. 168, No. 4, October 1985, p. 469

- ^ a b "FAO Workshop – Data Collection for the Pacific Region – FRA WP 51". fao.org. Archived from the original on 9 June 2013.

- ^ "Savaiʻi, Western Samoa, as a Pacific-Asia Biodiversity (PABITRA) Transect Site". Archived from the original on 13 July 2011. Retrieved 18 October 2009.

- ^ [2] Government of Samoa, 1998

- ^ Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment – Latest Articles Module Samoa Government Ministry of Natural Resources

- ^ "Species factsheet". Birdlife International. 2010. Archived from the original on 30 June 2007.

- ^ James Atherton, ed. (2010). "Report:Vaega Faʻatauainamole Faʻasaoi Samoa, Priority Sites for Con-servation in Samoa: Key Biodiversity Areas" (PDF). Conservation International – Pacific Islands Programme, Samoa Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment, Secretariat of the Pacific Regional Environment Programme.

- ^ "Samoan butterflies evolving fast". Discovery Channel News. 12 July 2007. Archived from the original on 12 October 2012.

- ^ "SAMOA ONLINE". wsamoa.ws. Archived from the original on 27 February 2012.

- ^ [3] Report to the Convention of Biological Diversity, Government of Samoa, 1998

- ^ "Samoa switches to driving on left". BBC News. 7 September 2009. Archived from the original on 5 August 2011.

- ^ "SavaiʻI Guide Overview". Archived from the original on 3 July 2009. Retrieved 22 September 2009.

- ^ [4] South Pacific Regional Environment Programme (SPREP), 21-7-2007. Retrieved 26 October 2009

- ^ "WEBSITE.WS – Your Internet Address For Life™". mysamoatours.ws. Archived from the original on 12 December 2013.

- ^ [5] Medicine Uncharted Organisation. Retrieved 25 April 2010 Archived 13 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ [6], Beach Fales:Sustainable Eco-Tourism and Cultural Preseravation in Samoa by Rachel Rasela Dolgin]

- ^ "Samoa to move the International Dateline". Herald Sun. 7 May 2011. Archived from the original on 2 May 2016.

- ^ "Global party reaches Hawaii". BBC News. 1 January 2000.

- ^ "Samoa A-Z Visitors Guide – safety, Samoa, Savaiʻi, Saʻmoana beach resort, scuba diving, shopping, sinalei reef resort & spa, siufaga beach resort, siva, smoking, sport & recreation, squash, stevenson, suicide, sun protection, sundays, supermarkets, surfing, swimming". Samoa A-Z Visitors Guide. Archived from the original on 3 March 2013.

- ^ "Satui'atua Beach Fales". samoa-hotels.com. Archived from the original on 25 July 2012.

- ^ "Samoa, an investment opportunity". South Pacific Development Group LLC. Archived from the original on 8 March 2012. Retrieved 6 July 2010.

- ^ Senara Brown, Alan Ah Mu (16 March 2010). "Casino warning". Samoa Observer. Archived from the original on 5 March 2012.

- ^ "SAVAII RESORT PROPOSAL RAISES CONCERN". Pacific Islands Report. 11 July 2008. Retrieved 6 February 2021.

- ^ "Samoa Hotel Association worried about size of Savaii project". RNZ. 10 July 2008. Retrieved 6 February 2021.

- ^ "Samoa department warns that sale of customary land is illegal". RNZ. 15 May 2002. Retrieved 6 February 2021.

- ^ "Samoa". U.S. Department of State.

- ^ Rottman, Gordon L. (2002). World War 2 Pacific island guide. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 88. ISBN 978-0-313-31395-0. Retrieved 26 July 2014.

- ^ a b "Samoa Found To Be in Path of Geological Hotspots, Adding Fuel To Debate Over Origins of Volcanic Chains". Science Daily. Adapted from materials provided by Oregon State University. 17 June 2008. Archived from the original on 14 May 2013.

- ^ Lippsett, Laurence (3 September 2009). "Voyage to Vailuluʻu". Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. Archived from the original on 6 March 2014.

- ^ Koppers, A. A.; Russell, J. A.; Staudigel, H.; Hart, S. R. (2006). "New 40Ar/39Ar Ages for Savaiʻi Island Reinstate Samoa as a Hotspot Trail with a Linear Age Progression". AGU Fall Meeting Abstracts. 2006: V34B–02. Bibcode:2006AGUFM.V34B..02K.

- ^ Hart; et al. (8 December 2000). "Vailuluʻu undersea volcano: The New Samoa" (PDF). G3, An Electronic Journal of the Earth Sciences, American Geophysical Union. Research Letter, Vol. 1. Paper number 2000GC000108. ISSN 1525-2027. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 February 2004.

- ^ "Savaiʻi". Archived from the original on 23 December 2010. Retrieved 23 December 2010. at OceanDots.com

- ^ a b "2010 School Calendar". Samoa Ministry of Education, Sports & Culture. Archived from the original on 12 February 2013. Retrieved 27 May 2010.

- ^ "Falealupo matai defend Nafanua Cox". Samoa Observer. 25 January 2009. Archived from the original on 5 March 2012.

- ^ "Strategic Policies and Plan, July 2006 – June 2015". Samoa Ministry of Education, Sports & Culture. 30 June 2006.

- ^ a b "Aid activities in Samoa". Government of Australia. Archived from the original on 6 March 2012. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ^ "NZAID Samoa". New Zealand Government. Archived from the original on 20 August 2010. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ^ "Activities in Samoa". Japan International Cooperation Agency. Archived from the original on 8 March 2012. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

- ^ "Savaiʻi Schools". Samoa Ministry of Education, Sports & Culture. Archived from the original on 20 December 2013. Retrieved 27 May 2010.

- ^ "History of Libraries in Samoa". Library Association of Samoa. Archived from the original on 27 November 2013. Retrieved 27 May 2010.

- ^ "Celebrations of Samoa's Independence Day". Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 20 October 2012. Retrieved 30 May 2010.

- ^ Garrett, John (1982). To live among the stars Christian origins in Oceania. University of the South Pacific. p. 126. ISBN 978-2-8254-0692-2. Retrieved 26 July 2014.

- ^ Pratt, George. "Title: A Grammar and Dictionary of the Samoan Language, with English and Samoan vocabulary, NZ Licence CC-BY-SA 3.0". NZ Electronic Text Centre, Victoria University of Wellington. Archived from the original on 18 March 2012. Retrieved 5 December 2009.

- ^ "Duke of Sussex presents innovation awards at Commonwealth 70th anniversary garden party | The Commonwealth". 11 April 2021. Archived from the original on 11 April 2021. Retrieved 28 October 2021.

- ^ "The journey of a survivor – Leilua receives Commonwealth Innovation award". ECPAT. 9 July 2019. Retrieved 28 October 2021.

- ^ "THE SAMOAN HISTORICAL CALENDAR, 1606–2007" (PDF). p. 37. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 December 2016.

- ^ Wilkes, Charles (1849). Narrative of the United States Exploring Expedition During the Years 1838, 1839, 1840, 1841, 1842. C. Sherman. p. 110.

External links

- Building a 3D model for land-use and nature conservation planning, Savaii Island, Samoa; Rudolf Hahn CTA FAO 2015 youtube video

- Looking for the Manumea. An ecological survey in community conservation areas, Savaii Island, Samoa; Rudolf Hahn CTA FAO 2014 youtube video

- "Savaiʻi". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution.

13°35′S 172°25′W / 13.583°S 172.417°W

- Final 2006 Samoa Census Report, Samoa Bureau of Statistics, July 2008

- Savaii Samoa Tourism Association

- Samoa Tourism Authority

- Sydney Morning Herald travel article June 2009

- Surfing Samoa on Youtube

- The Samoan Historical Calendar 1606 – 2007 by Stan Sorensen, Historian, Office of the Governor, American Samoa & Joseph Theroux

- First Samoan dictionary, 3rd edition (1893) by Rev. George Pratt

- Library Association of Samoa website