Angel Heart

| Angel Heart | |

|---|---|

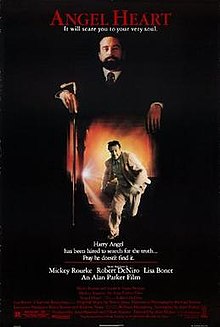

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Alan Parker |

| Screenplay by | Alan Parker |

| Based on | Falling Angel by William Hjortsberg |

| Produced by | |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Michael Seresin |

| Edited by | Gerry Hambling |

| Music by | Trevor Jones |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Tri-Star Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 113 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $18 million[1][2] |

| Box office | $17.2 million (domestic) |

Angel Heart is a 1987 American neo-noir psychological horror film, an adaptation of William Hjortsberg's 1978 novel Falling Angel. The film was written and directed by Alan Parker, and stars Mickey Rourke, Robert De Niro, Lisa Bonet, and Charlotte Rampling. Harry Angel (Rourke), a New York City private investigator, is hired to solve the disappearance of a man known as Johnny Favorite. His investigation takes him to New Orleans, where he becomes embroiled in a series of brutal murders.

Following publication of the novel, Hjortsberg began developing the screenplay for a film adaptation, but found that no major studio was willing to produce his script. The project resurfaced in 1985, when producer Elliott Kastner brought the book to Parker's attention. Parker began work on a new script and in doing so made several changes from Hjortsberg's novel. He also met with Mario Kassar and Andrew G. Vajna, who agreed to finance the $18 million production through their independent film studio Carolco Pictures. Filming took place on location in New York and New Orleans, with principal photography lasting from March 1986 to June of that year.

Weeks before its theatrical release, Angel Heart faced censorship issues from the Motion Picture Association of America for one scene of sexual content. Parker was forced to remove ten seconds of footage to avoid an X rating and secure the R rating that the film's distributor Tri-Star Pictures wanted. An unrated version featuring the removed footage was later released on home video.

Angel Heart received a mixed reaction from reviewers, who praised the performances of Rourke and Bonet, as well as the production design, score, and cinematography, but criticized Parker's screenwriting. The film underperformed at the North American box office, grossing $17.2 million during its theatrical run, but has since been regarded as underappreciated and influential.

Plot

In 1955, New York City private investigator Harry Angel is contacted by a man named Louis Cyphre to track down John Liebling, a crooner known professionally as Johnny Favorite who suffered severe neurological trauma, resulting from injuries received in World War II. Favorite's incapacity disrupted a contract with Cyphre regarding unspecified collateral, and Cyphre believes a private hospital where Favorite was receiving radical psychiatric treatment for shell shock has falsified records.

At the hospital, Harry discovers the records showing Favorite's transfer were indeed falsified by a physician named Albert Fowler. After Harry breaks into his home, Fowler admits that years ago he was bribed by a man and woman so that the two could abscond with the disfigured Favorite. Believing that Fowler is still withholding information, Harry locks him in his bedroom, forcing him to suffer withdrawal from a morphine addiction. The next morning, he finds that the doctor has apparently committed suicide.

Harry tries to break his contract with Cyphre but agrees to continue the search when Cyphre offers him a lot of money. He discovers that Favorite had a wealthy fiancée named Margaret Krusemark but had also begun a secret affair with a woman named Evangeline Proudfoot. Harry travels to New Orleans and meets with Margaret, who tells him Favorite is dead, or at least dead to her. Evangeline died years before but is survived by her 17-year-old daughter, Epiphany Proudfoot, who was conceived during her mother's affair with Favorite.

When Epiphany is reluctant to speak, Harry tracks down Toots Sweet, a guitarist and former Favorite bandmate. After Harry uses force to try to extract details of Favorite's last known whereabouts, Toots refers him back to Margaret. The following morning, police detectives inform Harry that Toots has been murdered. Harry returns to Margaret's home and finds her murdered, her heart removed with a ceremonial knife. He is later attacked by enforcers of Ethan Krusemark—a powerful Louisiana patriarch and Margaret's father—who tell him to leave town.

At his hotel, Harry finds Epiphany. He invites her into his room, where they have sex during which Harry has visions of blood dripping from the ceiling and splashing around the room. He later confronts Krusemark in a gumbo hut, where the latter reveals that he and Margaret were the ones who took Favorite from the hospital. Favorite was actually a powerful occultist who sold his soul to Satan in exchange for stardom. He got his stardom but then sought to renege on the bargain. To do so, Favorite kidnapped a young soldier that was the exact same age and resemblance to Favourite from Times Square and performed a Satanic ritual on the boy, murdering him and eating his still-beating heart in order to steal his soul. Favorite planned to assume the identity of the murdered soldier but was drafted and then injured overseas. Suffering severe facial trauma and amnesia, Favorite was sent to the hospital for treatment.

After Krusemark and his daughter took him from the hospital, they left him at Times Square on New Year's Eve 1943 (the date on the falsified hospital records). While hearing Krusemark's story, Harry runs into the bathroom, vomits and continually asks the identity of the soldier. He returns to find Krusemark drowned in a cauldron of boiling gumbo.

At Margaret's home, Harry finds a vase containing the soldier's dog tag—stamped with the name Angel, Harold. Harry realizes he and Johnny Favorite are, in fact, the same person. Cyphre, whose name is a homophone for Lucifer, appears. His true nature revealed, Cyphre proclaims that he can at long last claim what is his: Favorite's immortal soul. Harry insists that he knows who he is and has never killed anyone, but as he looks at his reflection in a mirror, his repressed memories showing him killing Fowler, Toots, the Krusemarks, and Epiphany come flooding back.

A frantic Harry returns to his hotel room, where the police have found Epiphany murdered. Harry's dog tags are on her body. A police officer enters the room carrying Epiphany's young son, who Harry realizes is his grandchild. Harry sees the child's eyes glow, just as Cyphre's had at their last meeting, implying that Satan is the mysterious entity that impregnated Epiphany. Harry later is seen standing inside an elevator that is interminably descending, presumably to Hell. Cyphre can be heard whispering, "Harry" and "Johnny", asserting dominion over both their souls.

Cast

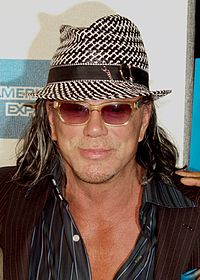

- Mickey Rourke as Harry Angel

- Robert De Niro as Louis Cyphre

- Lisa Bonet as Epiphany Proudfoot

- Charlotte Rampling as Margaret Krusemark

- Stocker Fontelieu as Ethan Krusemark

- Brownie McGhee as Toots Sweet

- Michael Higgins as Dr. Albert Fowler

- Elizabeth Whitcraft as Connie

- Charles Gordone as Spider Simpson

- Dann Florek as Herman Winesap

- Kathleen Wilhoite as Nurse

- Pruitt Taylor Vince as Detective Deimos

Production

Development

"The original attraction was the fusion of two genres—the detective film and the supernatural."

Following publication of his 1978 novel Falling Angel, William Hjortsberg began work on a film adaptation. His friend, production designer Richard Sylbert, took the book's manuscript to producer Robert Evans.[5] The film rights to the novel had been optioned by Paramount Pictures, with Evans slated to produce the film, John Frankenheimer hired to direct, and Hjortsberg acting as screenwriter.[6] Frankenheimer was later replaced by Dick Richards, and Dustin Hoffman was being considered for the lead role.[6] After Paramount's option expired, Hjortsberg discussed the project with Robert Redford and wrote two drafts. Hjortsberg, however, felt that no film studio was willing to produce his script. He reflected, "Even with [Redford] behind the script, studio executives weren't interested. 'Why can't it have a happy ending?' every bigshot demanded."[5]

In 1985, producer Elliott Kastner met with Alan Parker at Pinewood Studios to discuss a film adaptation of the novel. Parker, who had read the book following its publication, agreed to write the screenplay. He met with Hjortsberg in London[5] before moving to New York, where he wrote most of the script.[3][7] After completing the first draft in September 1985, Parker traveled to Rome, Italy, where he brought the script to Mario Kassar and Andrew G. Vajna. The two producers agreed to finance the film through their independent film studio, Carolco Pictures,[3][7] and Parker was given creative control.[8] Pre-production work on Angel Heart began in January 1986 in New York, where Parker selected the creative team, reuniting with several of his past collaborators, including producer Alan Marshall, director of photography Michael Seresin, camera operator Michael Roberts, production designer Brian Morris and editor Gerry Hambling.[7]

Writing

Parker made several changes from the novel. He titled his script Angel Heart as he wanted to distance his film adaptation from the source material.[7] While Falling Angel is set entirely in New York City, Parker had the second half of his script take place in New Orleans, based on the novel's perpetual allusions to voodoo and the occult.[3] He discussed the story-setting change to Hjortsberg, who approved of the decision; the author revealed to Parker that he had also thought of setting his novel in New Orleans.[7] Angel Heart is set in the year 1955, whereas in the book the events take place in 1959. He explained, "The book is set in 1959 and I moved it to 1955 for a small but selfish reason. 1959 was on the way to the 1960s with its changing attitudes as well as environments. 1955 for me still belonged to the 1940s—and, because of the historical pause button of World War II, conceivably the 1930s—so quite simply, setting it in this year allowed me to give an older look to the film."[7]

Other script changes from the novel involved characterization and dialogue. Parker sought to make Harry Angel a character that evoked sympathy. He said, "In the tradition of the down-at-heel gumshoe, his phlegmatic surface disguised an intelligence capable of unraveling a complicated, larger-than-life story with a degree of belief and conciseness. Also he had to be attractive to audiences while enlightening them, little by little, along the way."[7] Parker also established Angel as being born on February 14—Valentine's Day—the same date as his own birthday. He explained that it was "for no particular reason other than Valentine’s Day might be easy to remember in a labyrinthine script and the heart reference seemed to have some resonance".[7] Parker also wanted to create a realistic depiction of Louis Cyphre, as opposed to the character's "larger-than-life" personality in the novel.[7] Another script change involved the ending and the identity of the killer. While Angel is framed for the murders (presumably by Cyphre) in the novel, Parker established the character as the killer for the film's ending.[3]

Casting

Parker originally wanted Robert De Niro to play the role of Harry Angel, but the actor expressed interest in making a cameo appearance as mysterious benefactor Louis Cyphre. De Niro, however, did not fully commit to the role until after frequent discussions with Parker. The director reflected, "I had been courting [De Niro] to play [Cyphre] in Angel Heart for some months and we had met a few times—and he had continued to bombard me with questions examining every dot and comma of my script. I had walked him through the locations we had found, read through the screenplay sitting on the floor of a dank, disused church in Harlem and finally he said ‘yes’."[7]

Jack Nicholson and Mickey Rourke were also considered for the role of Angel. Parker met with Nicholson in Los Angeles to discuss the project. Nicholson ultimately passed on the role. Parker said, "I did my pitch and he was most gracious, although, to be honest, he was quite distracted at the time... my movie and the possibility of him taking part seemed to slip from his immediate area of concentration and interest."[7] Parker then met with Rourke, who expressed a strong interest in playing Angel and secured the leading role after a meeting with Parker in New York.[3][7]

Various actresses auditioned for the role of Epiphany Proudfoot before Lisa Bonet secured the part. Bonet was then known for her role on the family-oriented sitcom The Cosby Show, and her casting in Angel Heart sparked significant controversy.[9] Before securing the role, Bonet discussed it with Bill Cosby, who encouraged her decision to appear in the film.[9] Parker cast Bonet based on the strength of her audition[7] and was unaware of her role on The Cosby Show.[3] "I didn't hire [Bonet] because of The Cosby Show," he said. "I have never even seen the show. I hired her because she was right for the role."[10] On preparing for the role, Bonet said, "I did a lot of meditation and a lot of self-inquiry. I did some research on voodoo. My earnest endeavor was really to let go of all my inhibitions. It was really necessary for me to be able to let go of Lisa and let Epiphany take over."[11]

Parker had difficulty finding an actress for the role of Margaret Krusemark. "Although it’s a small part in the film, the character is omnipresent in the dialogue and [the actress] had to have the right balance of class and eccentricity," he said. "I read many actresses for the part without much success." Rourke then suggested English actress Charlotte Rampling, who secured the role after Parker contacted her to discuss the part.[3][7]

In January 1986, Parker held an open casting call at a New York nightclub known as The Kamikaze, with more than 1,400 people auditioning for various roles. "I managed to read a short scene with 600 of them as they were filtered through to me," he said.[7] Actress Elizabeth Whitcraft, who had a small role in Parker's previous film Birdy was cast as Connie, a journalist who aids Angel in his investigation.[3][7] Parker held another casting call in New Orleans, where he requested that local musicians audition for possible roles in the film. Clarence "Gatemouth" Brown and Deacon John Moore were among the many musicians who auditioned for roles. Moore was cast as Toots Sweet's bandmate.[7] Parker then returned to New York, where he auditioned other musicians, including Bo Diddley and Dizzy Gillespie. Blues guitarist Brownie McGhee, who plays Toots Sweet, was cast during the film's principal photography.[7]

Filming

During the casting process, Parker and producer Alan Marshall began scouting locations in New York City. The director looked at Harlem, believing that the neighborhood was "as un-photographed as other parts of New York are over-used."[7] On January 20, 1986, he travelled to New Orleans, where he continued writing the script. Parker looked at unused buildings located on Royal Street that would act as a hotel and an abandoned house on Magazine Street that would serve as the home of Margaret Krusemark (Rampling).[7] He returned to New York, where he looked at Staten Island and Coney Island.[7] Parker's script for Angel Heart required that a total of 78 locations be used for filming between New York and New Orleans.[7]

Principal photography for Angel Heart began on March 31, 1986, and concluded on June 20, 1986,[7] on a budget of $18 million.[1][2] Filming began in Eldridge Street, Manhattan, New York City, which acted as Harry Angel's neighbourhood. Production designer Brian Morris and the set-decorating team spent two months designing the set prior to filming, hoping to recreate 1950s New York. Because of the warm weather conditions, ice trucks were used to create fake snow.[7] Filming then moved to Alphabet City in Manhattan, where several bar scenes and Angel's intimate bedroom scene with Connie (Whitcraft) were filmed.[7]

The production then moved to Harlem to film a chase scene set during a procession before moving to Coney Island, where the cast and crew underwent severely cold weather conditions. The location was used to film a scene in which Angel questions a man, Izzy (George Buck), about the whereabouts of Johnny Favorite while Izzy's wife Bo (Judith Drake) stands waist deep in the ocean. The original actress who was cast as Bo was injured when she was knocked off her feet by a wave while delivering her first line. The actress refused to reshoot the scene, which led to her being replaced by her stand-in, Drake, whom Parker found to be a better actress for the role.[7]

Production returned to Manhattan to film the opening credits sequence.[7] Filming then moved to Harlem, New York, where a hospice was used to film a scene involving the character Spider Simpson (Charles Gordone), and many of the hospice's elderly residents acted as extras for the scene.[7] On April 17, 1986, the production team moved to Staten Island to film exterior and interior scenes involving the character Dr. Fowler (Michael Higgins). Filming then moved to Hoboken, New Jersey, which doubled for a scene set in a New Orleans train station. From April 28 to April 29, 1986, the Angel Heart production team returned to Harlem, where Parker filmed Rourke and De Niro's scene in a Harlem mission. The two actors next filmed a scene at Lanza's, an Italian restaurant located on the Lower East Side.[7]

By May 3, 1986, production had moved to New Orleans.[7] In the town of Thibodaux, Louisiana, Parker and his crew discovered an entire plantation workers' village that would serve as a graveyard. He said, "We had the good fortune to find an entire plantation workers’ village almost intact and, with careful dressing, this became Epiphany's world. The graveyard was a dressed set, but much of what we filmed was already there."[7] An unused Louisiana field was used to create a racetrack where Angel meets the wealthy patriarch Ethan Krusemark (Fontelieu).[7] On May 13, the crew encountered some difficulty filming a chase scene involving Angel, as they had to deal with shying horses, trained dogs, gunshots, two hundred chickens, and a horse specially trained to fall on top of Rourke’s stuntman.[3][7]

Production then moved to Magazine Street, where production designer Brian Morris and the art department attempted to recreate 1950s New Orleans. Parker said of the set, "As in New York, we had dressed and clad every single storefront as far as the eye could see in order to be authentic to the period, and drained everything of all primary colours for our monochromatic look."[7] Filming then moved to Jackson Square where the crew filmed one of the final scenes, in which Angel runs from Margaret's home. The production then filmed a voodoo ceremony scene choreographed by Louis Falco. Falco, who had previously choreographed Parker's 1980 film Fame, based the scene on an actual Haitian ceremony.[7]

The sex scene involving Rourke and Bonet was filmed in one of the unused buildings located on Royal Street and took four hours to shoot. Parker limited the crew to himself, cinematographer Michael Seresin, camera operator Michael Roberts, and the camera assistant. To make the actors more comfortable, Parker played music during the shoot.[7] Production then moved to a corner of New Orleans, which doubled for flashback sequences set in 1943 Times Square, New York. The crew then discovered an unused bus depot, which was used to film scenes set in Ethan Krusemark's gumbo hut.[7] Filming then moved to the St. Alphonsus Church, where the crew filmed a dialogue scene between Angel and Cyphre.[7] Production returned to Royal Street in the French Quarter, where the final confrontation between Angel and Cyphre and the film's ending were shot.[7]

Editing and censorship

"[The MPAA] can't ban a movie but this is, in a way, blackmail. I think I'm a responsible film maker. I had complete creative freedom, so if there's anything offensive about Angel Heart, I'm responsible for it."

—Parker on the MPAA's decision to give Angel Heart an X rating.[8]

After filming concluded in June 1986, Parker spent four months editing the film in Europe, with 400,000 feet of film and 1,100 different shots.[7] The Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) gave the original cut of Angel Heart an X rating, which is widely associated with pornographic films.[8] The board, composed of industry executives and theater owners,[8] expressed concerns over several seconds of the sex scene involving Rourke and Bonet in which Rourke's buttocks are seen thrusting in a sexual motion.[3][7] Parker appealed the rating but did not receive the two-thirds vote required to reclassify the film to an R rating.[8]

The film's distributor Tri-Star Pictures refused to release it with an X rating, as the film would have fewer theaters willing to book it and fewer venues for advertising;[8] Steve Randall, executive vice president of marketing for Tri-Star, stated that it was the studio's "firm policy not to release an X-rated film."[8] With only a few weeks before the film's release, the studio was desperate for the less-restrictive R rating, but Parker was reluctant to alter the film.[3] He filed another appeal,[8] on which the board voted 8 to 6 in favor of the X rating.[12] Parker then removed ten seconds of sexual content from the scene.[13] "That scene was very complex, very intricate, and the cutting quite rapid, involving 60 to 80 cuts in the space of about two minutes," he said. "Eventually, I cut only 10 seconds from the scene, or about 14 feet of film."[1] On February 24, 1987, the film was granted an R rating.[14] Parker later stated that the MPAA's concerns led to "a wasteful, pointless and expensive exercise".[7]

Music

The score was produced and composed by Trevor Jones, with saxophone solos by British jazz musician Courtney Pine.[7][15][16] Parker hired Jones based on his work for the 1986 film Runaway Train.[15] After meeting with the director, Jones viewed a rough cut version of the film. He stated, "When I sat in the screening room all by myself and began to see those images, I was shaking like a puppy when the movie ended and when I got out of the room I told [Parker] that it was a great picture, but that I didn’t understand what exactly he wanted from me. He told me that he expected me to deliver something special to the picture and… to approach the movie from whenever I chose."[17]

For the score, Jones wanted to explore the concept of evil, explaining, "Evil is the greatest of human fears… I tried to give that feeling to the score using daily ordinary music that would bridge the world of [Harry Angel] to that which he’s getting into, the black magic, his search. It was like a psychological journey for me always trying to relate to the fears and emotions of the audience."[17] He composed the score electronically on a Synclavier.[18] Parker chose Glen Gray's 1937 song "Girl of My Dreams" as a recurring song performed by the unseen character Johnny Favorite. He wanted the song to act as a motif that would haunt viewers as it had haunted Harry Angel. Jones incorporated elements of the song into his score.[15]

In addition to Jones's compositions, the soundtrack features a number of blues and R&B performances, including "Honeyman Blues" by Bessie Smith, and "Soul on Fire" by LaVern Baker. Brownie McGhee performed the songs "The Right Key, but the Wrong Keyhole" and "Rainy Rainy Day" for the film, with Lilian Boutte acting as a vocalist.[16] Jones stated, "…the main bulk of the score was worked on with a Synclavier. Basically there were two types of music, one was the electronic stuff from the Synclavier that [Parker] wanted, and the real jazz musicians. The two work very well together in view of the film's intent."[18]

During post-production, Jones mixed the music tracks at Angel Recording Studios, a recording studio built in an abandoned church in Islington, North London, with final mixing taking place at Warner Hollywood Studios in Los Angeles.[15] Parker said, "One of the great advantages of working with contemporary recording techniques is that we can mix onto film in a recording studio with all of the various components and options of modern, multi-track recordings. I’ve always been very mistrustful of conventional scoring, whereby a hundred musicians sit in front of the projected film and the conductor strikes up the orchestra."[7] A motion picture soundtrack album was released by the recording labels Antilles Records and Island Records.[19][20]

Release

In North America, Angel Heart opened in wide release on March 6, 1987, distributed by Tri-Star Pictures.[21] The film debuted at number four at the weekend box office, garnering ticket sales of $3,688,721 from 815 screens, with an average of $4,526 per theatre. The film's overall domestic gross was $17.2 million,[21] against a production budget of $18 million.[1][2]

Reception

The review aggregation website Rotten Tomatoes gave Angel Heart a score of 82% based on a sample of 33 reviews, with an average score of 7.4/10. The site's consensus reads: "Angel Heart lures viewers into its disturbing, brutal mystery with authentic noir flair and a palpably hypnotic mood".[22] William Hjortsberg, author of Falling Angel, voiced his support of the film adaptation, stating, "[Alan] Parker wrote an excellent script and went on to make a memorable film. Casting Robert De Niro as Cyphre was a brilliant touch."[5] Although initially supportive of Bonet's decision to appear in the film, Bill Cosby dismissed Angel Heart as "a movie made by white America that cast a black girl, gave her voodoo things to do and have sex".[23]

Initial reactions among film critics were mixed; The Hollywood Reporter indicated that reviewers generally praised Rourke's performance, as well as the score, cinematography, and production design, while criticism was aimed at Parker's screenwriting for being convoluted and exposition-heavy.[6] Vincent Canby of The New York Times praised the cinematography and production design, but criticized Rourke's performance as being "suitably intense, but to such little effect".[24] Rita Kempley of The Washington Post wrote that Angel Heart "is over-stylized, and we're over-stimulated when the soundtrack goes berserk, from a few thumpity-thumps to a visceral, ventricles a-pumping score".[25] Pauline Kael of The New Yorker criticized Parker's direction: "There's no way to separate the occult from the incomprehensible... Parker simply doesn't have the gift of making evil seductive, and he edits like a flasher."[26] Kael also criticized De Niro's cameo appearance, writing, "It’s the sort of guest appearance that lazy big actors delight in—they can show up the local talent."[27]

On the syndicated television program Siskel & Ebert & the Movies, Gene Siskel gave Angel Heart a "thumbs down", while his colleague Roger Ebert praised the film and gave it a "thumbs up".[28] In his review for the Chicago Tribune, Siskel wrote that "Parker seems more concerned with style and with hiding the film`s big mystery than with pacing."[29] Siskel also criticized the film's controversial sex scene for not being "as shocking as the rating board would have you believe."[29]

Ebert, writing for the Chicago Sun-Times, gave the film three and a half stars out of four, writing that "Angel Heart is a thriller and a horror movie, but most of all it's an exuberant exercise in style, in which Parker and his actors have fun taking it to the limit".[30] Ian Nathan of Empire called the film "A diabolical treat with Rourke and De Niro in top form."[31] Almar Haflidason of the BBC wrote, "The movie maintains intrigue at every turn and Rourke is spellbinding. Robert De Niro, Charlotte Rampling, and the assembled cast are all excellent. But this is Mickey Rourke's movie, and he puts in a mesmerising performance."[32] Richard Luck, writing for Film4, concluded in his review, "The book's so good it deserves a better movie, but Rourke's performance is such that Angel Heart stands out from the necromancy movie crowd."[33]

Cultural impact

Filmmaker Christopher Nolan stated the film was a major influence on his 2000 film Memento: "In terms of Memento, Alan Parker films such as Angel Heart and The Wall, which use very interesting editing techniques such as a fractured narrative, were a big influence."[34]

In 2010, Wired magazine ranked the film at number 22 on their list of "The 25 Best Horror Films of All Time",[35] and in 2012, Mark Hughes, writing for Forbes, ranked Angel Heart at number nine on his list of the "Top 10 Best Cult Classic Horror Movies of All Time".[36] Den of Geek writer Ryan Lambie ranked the film at number six on his list of "The Top 20 Underappreciated Films of 1987", writing that "Parker brings a wonderfully shadowy quality to his noir thriller, which takes in New York and New Orleans. Some viewers may be able to predict where this twisty, murky thriller's going to take them, but the ride remains one worth taking thanks to the quality of the acting and direction."[37] Film critic Tim Dirks of the film-review website Filmsite.org added the film to his list of films featuring the "Greatest Film Plot Twists, Film Spoilers and Surprise Endings", based on two of the film's major plot twists—Harry Angel being revealed as Johnny Favorite, and Louis Cyphre revealing himself as Lucifer.[38] Screen Rant writer Tim Butters rated Robert De Niro's performance "One of the 10 Best Movie Depictions of the Devil".[39]

Accolades

Angel Heart received several awards and nominations following its release. At the 10th Jupiter Awards, Mickey Rourke won a Jupiter Award for Best International Actor for his performances in both Angel Heart and A Prayer for the Dying (1987).[40] At the 9th Youth in Film Awards, Lisa Bonet won the Young Artist Award for Best Young Female Superstar in Motion Pictures.[41] At the 15th Saturn Awards, Angel Heart received three Saturn Award nominations, though it failed to win any.[42]

| Award | Category | Recipient(s) and nominee(s) | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 15th Saturn Awards[42] | Best Supporting Actor | Robert De Niro | Nominated |

| Best Supporting Actress | Lisa Bonet | Nominated | |

| Best Writing | Alan Parker | Nominated | |

| 10th Jupiter Awards[40] | Best International Actor | Mickey Rourke | Won[a] |

| 9th Youth in Film Awards[41] | Best Young Female Superstar in Motion Pictures | Lisa Bonet | Won |

Home video

Angel Heart was released on VHS on September 24, 1987, by International Video Entertainment (IVE).[43] The releases included the R-rated theatrical cut and an uncut version which restored the ten seconds of sexual content that was removed to satisfy the MPAA.[44] Ralph King, senior vice president of IVE, said, "The scene cut from Angel Heart is both provocative and shocking, but it is by no means pornographic. We're pleased to give the public the opportunity to see the film as Alan Parker originally meant the film to be viewed."[43]

The film was first released on DVD on June 23, 1998, by Artisan Entertainment.[45] Special features on the DVD included a theatrical trailer, production notes, a making-of featurette, and information on the cast and crew.[46] The DVD release received criticism for its poor video transfer and shortage of special features.[47] Artisan later released the film on laserdisc on August 18, 1998.[48] Lionsgate Home Entertainment re-released Angel Heart with a "Special Edition" DVD on May 18, 2004.[47][49] The Special Edition features additional material, including an introduction and audio commentary by Parker, a scene-specific commentary by Rourke, a video interview with the actor, and the theatrical trailer.[47] Lionsgate released the film on Blu-ray on November 24, 2009. The Blu-ray presents the film in 1080p high definition and contains all the additional materials found on the Special Edition DVD.[50]

On July 12, 2022, Lionsgate released the film on 4K Ultra HD for the first time in the United States.[51]

TV version

An edited TV version was produced which removed the more graphic elements of the sex scenes. In particular the sex scene between Mickey Rourke and Lisa Bonet was completely re-edited and featured additional footage that was not included in either the R or Unrated versions. The additional footage features flashbacks of a drunken party with several scantily clad women at the barracks where Johnny Favorite was stationed just prior to it being hit by a series of explosions. The sequence ends with a brief shot of Epiphany Proudfoot's (presumably dead) body burning amongst a pile of charred rubble.

Deleted scenes

- A graphic sequence in which Herman Winesap is decapitated by the blades of a rotary fan was shot but not used in the final cut.

- When Harry murders Toots Sweet there was additional footage of Harry writing the words "TELOCA" on the wall in the victims blood. The word is taken from the Enochian book of magic, meaning "Damned".

- Harry's girlfriend, the New York Times secretary Connie, was originally revealed to have also been murdered, presumably by Harry shortly after their brief encounter, with her corpse being found burned to death.

Remake

In 2008, it was announced that producers Michael De Luca, Alison Rosenzweig and Michael Gaeta were developing a planned remake of Angel Heart that would be produced by De Luca's production banner, Michael De Luca Productions.[52] The producers had optioned the rights to both the film and the novel Falling Angel.[52] De Luca expressed that he was a fan of the novel, stating, "It’s a great blend of genres with a great Faustian bargain, compelling, universal themes and a rare combination of literary and commercial appeal."[52] However, nothing has been heard of this project since a brief Filmstalker article in May 2009.[53]

Notes

- ^ Rourke won the award for his performances in both Angel Heart and A Prayer for the Dying.

References

- ^ a b c d "Parker Avenges 'Angel Heart' Censoring". Sun-Sentinel. United Press International. August 3, 1987. Archived from the original on April 6, 2016. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- ^ a b c Matthews, Jack (February 23, 1987). "Parker Avenges 'Angel Heart' Censoring". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l David F. Gonthier, Jr.; Timothy L. O'Brien (May 2015). "8. Angel Heart, 1987". The Films of Alan Parker, 1976–2003. United States: McFarland & Company. pp. 138–61. ISBN 978-0-78649725-6.

- ^ Parker, Alan (November 24, 2009). Audio commentary for Angel Heart (Blu-ray). Lionsgate, StudioCanal.

- ^ a b c d Hjortsberg, William. "Angel Heart". Archived from the original on October 6, 2016. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- ^ a b c "Angel Heart". AFI Catalog. American Film Institute (AFI). Retrieved January 1, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar Parker, Alan. "Angel Heart". Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Harmetz, Aljean (February 14, 1987). "X rating for 'Angel Heart' is upheld". The New York Times. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- ^ a b Valle, Victor (February 26, 1987). "Bonet's 'Angel' Heartache". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- ^ Valle, Victor (March 2, 1987). "Actress Lisa Bonet transcends to the 'Angel Heart' controversy". Reading Eagle. Reading, Pennsylvania. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- ^ Frazier, Tony (March 13, 1987). "Cosby Kid' Not Concerned About Her Image". News OK. News OK. Archived from the original on April 22, 2016. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- ^ "Appeals Board Upholds 'Angel Heart' X Rating". The New York Times. February 21, 1987. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- ^ Harmetz, Aljean (March 7, 1987). "'Angel Heart' refuels ratings controversy". Observer–Reporter. Washington, Pennsylvania. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- ^ "'Angel Heart' Gets Its R". Sun-Sentinel. February 26, 1987. Archived from the original on April 7, 2016. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- ^ a b c d Parker, Alan. Angel Heart (Original Soundtrack Album) (LP record cover). United Kingdom: Antilles Records, Island Records. Back of album cover. 5014474287091.

- ^ a b "Angel Heart Soundtrack CD Album". CD Universe. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- ^ a b Benitez, Sergio. "Two Days with Trevor Jones at the Phone (First Day)". BSO Spirit. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- ^ a b Larson, Randall D. (June 12, 2013). "An Interview with Trevor Jones by Randall D. Larson". The CinemaScore & Soundtrack Archives. CinemaScore. Retrieved April 7, 2016.

- ^ "Angel Heart (Original Soundtrack Music) - Trevor Jones". AllMusic. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- ^ "Angel Heart Soundtrack (complete album tracklisting)". SoundtrackINFO. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- ^ a b "Angel Heart". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- ^ "Angel Heart". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango. Retrieved September 1, 2022.

- ^ Coker, Hillary Crosley (8 January 2015). "Lisa Bonet: The Cosby Show Kid Who Got Away". The Muse. Retrieved April 6, 2016.

- ^ Canby, Vincent (March 6, 1987). "Movie Review - Angel Heart - FILM: MICKEY ROURKE STARS IN 'ANGEL HEART'". The New York Times. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- ^ Kempley, Rita (March 6, 1987). "Angel Heart". The Washington Post. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- ^ "Kael Reviews: Angel Heart". Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- ^ Bosworth, Patricia (October 1987). "The Secret Life of Robert De Niro". Vanity Fair. Condé Nast. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- ^ Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert (February 28, 1987). Siskel and Ebert and the Movies.

- ^ a b Siskel, Gene (March 6, 1987). "Flick Of Week: 'Angel Heart' Beating At A Sluggish Pace - tribunedigital-chicagotribune". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (March 6, 1987). "Angel Heart". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on May 27, 2011. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- ^ Nathan, Ian (January 1, 2000). "Angel Heart Review". Empire. Empire. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- ^ Haflidason, Almar (January 25, 2001). "BBC - Films - review - Angel Heart". BBC. BBC. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- ^ Luck, Richard. "Angel Heart - Film4". Film4. Channel Four Television Corporation. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- ^ "Metropolis - In Person". Metropolis. Metropolis. Archived from the original on January 2, 2016. Retrieved March 28, 2016.

- ^ Snyder, Jon (October 28, 2010). "The 25 Best Horror Films of All Time (NSFW)". Wired. Wired. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- ^ Hughes, Mark. "Top 10 Best Cult Classic Horror Movies Of All Time". Forbes. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- ^ Lambie, Ryan (February 23, 2018). "The Underrated Movies of 1987". Den of Geek. Retrieved April 19, 2021.

- ^ Dirks, Tim. "Greatest Movie Plot Twists, Spoilers and Surprise Endings". Filmsite.org. American Movie Classics Company, Inc. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- ^ Butters, Tim (November 7, 2015). "10 Best Movie Depictions of the Devil". Screen Rant. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- ^ a b Jupiter Awards. "Alle JUPITER AWARD-Gewinner 1978-2014". Jupiter Awards. Retrieved March 27, 2016.

- ^ a b "9th Annual Awards". Young Artist Awards. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved March 27, 2016.

- ^ a b "'Robocop' Leads In Nominations for Saturn Awards". AP News archive. Associated Press. April 7, 1988. Retrieved March 27, 2016.

- ^ a b "'Angel Heart' Video To Be Uncut - tribunedigital-sunsentinel". Sun-Sentinel. Entertainment News Service. June 26, 1987. Archived from the original on April 6, 2016. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- ^ Harmetz, Aljean (July 23, 1987). "Video of 'Angel Heart' Restores Edited Scene". The New York Times. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- ^ Goldsetein, Seth (May 2, 1998). "Catalog Duplication Process Threatened; Paramount Presence in DVG Possible". Billboard. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- ^ "Angel Heart". Ekoliniol. Archived from the original on April 3, 2016. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- ^ a b c "Angel Heart (Special Edition)". DVD Talk. May 30, 2004. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- ^ "Angel Heart [LD60457-WS]". LaserDisc Database. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- ^ "Angel Heart DVD: Special Edition". Blu-ray. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- ^ "Angel Heart Blu-ray". Blu-ray. Retrieved March 23, 2016.

- ^ "Angel Heart 4K Blu-ray (SteelBook)", Blu-ray, retrieved 2022-08-29

- ^ a b c Siegel, Tatiana (September 30, 2008). "Trio developing 'Angel Heart' remake". Variety. Retrieved March 26, 2016.

- ^ Brunton, Richard (May 14, 2009). "Angel Heart remake still on". Filmstalker. Retrieved July 12, 2021.

External links

- Angel Heart at AlanParker.com

- Angel Heart at IMDb

- Angel Heart at AllMovie

- Angel Heart at Rotten Tomatoes

- Angel Heart at Box Office Mojo

- 1987 films

- 1987 horror films

- 1980s mystery thriller films

- 1980s erotic thriller films

- Films about Voodoo

- Fiction about Louisiana Voodoo

- Films about sexuality

- American psychological horror films

- American mystery thriller films

- American erotic horror films

- 1980s English-language films

- American detective films

- Films about amnesia

- American neo-noir films

- Southern Gothic films

- American supernatural thriller films

- Films directed by Alan Parker

- Films scored by Trevor Jones

- Films set in 1955

- Films set in New Orleans

- Films set in New York City

- Films shot in New Orleans

- Films shot in New York City

- Occult detective fiction

- Incest in film

- American independent films

- Carolco Pictures films

- TriStar Pictures films

- The Devil in film

- Works based on the Faust legend

- Fiction with unreliable narrators

- Films based on American novels

- Films with screenplays by Alan Parker

- 1980s supernatural films

- Films produced by Elliott Kastner

- Rating controversies in film

- Cockfighting in film

- 1980s American films

- Films about identity theft

- Films produced by Alan Marshall (producer)