Dzhokhar Dudayev

Dzhokhar Dudaev | |

|---|---|

Дудин Джохар | |

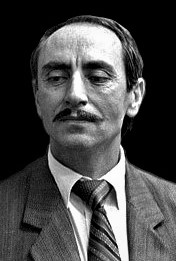

Dzhokhar Dudayev in September 1991 | |

| 1st President of the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria | |

| In office 1 November 1991 – 21 April 1996 | |

| Vice President | Zelimkhan Yandarbiyev |

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | Zelimkhan Yandarbiyev (acting) |

| Prime Minister of Ichkeria | |

| In office 9 November 1991 – 21 April 1996 | |

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | Zelimkhan Yandarbiyev |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Dzhokhar Musayevich Dudaev 15 February 1944[1] Yalkhoroy, Chechen-Ingush ASSR, Soviet Union |

| Died | 21 April 1996 (aged 52) Gekhi-Chu,[2] Chechen Republic of Ichkeria |

| Manner of death | Assassination by guided missile |

| Nationality | Chechen |

| Political party | CPSU (1968–1990) NCChP (1990–1996) |

| Spouse | Alla Dudayeva |

| Children |

|

| Profession | Military aviator |

| Signature |  |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | Soviet Air Force Armed Forces of Ichkeria |

| Years of service | 1962–1990 1991–1996 |

| Rank | Major general |

| Commands | 326th Heavy Bomber Aviation Division (1987–1991) All (supreme commander, 1991–1996) |

| Battles/wars | First Chechen War X |

Dzhokhar Musayevich Dudayev[b] (15 February 1944 – 21 April 1996) was a Chechen politician, statesman and military leader of the 1990's Chechen Independence movement from Russia. He served as the first president of the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria, from 1991 until his assassination in 1996. Previously he had been a Major General of Aviation in the Soviet Armed Forces.

Dzhokhar and his family, along with the entire Chechen nation, had been deported to Siberia in 1944 by the Soviet regime in a case of genocide as part of a Soviet forced resettlement program that affected several million members of ethnic minorities in the Soviet Union between the 1930s and the 1950s. His family was allowed to return to his native Chechnya in 1956, after Stalin’s death. From 1962 he served in the Soviet Air Force, reaching the rank of Major General. He commanded strategic nuclear bomber aircraft divisions located in Poltava and Tartu. For his merits, he was awarded several state orders of the USSR, most notably the Order of the Red Banner and the Order of the Red Star.

In 1991, Dudayev refused Soviet orders to crush Estonia's drive for independence and subsequently resigned from the Soviet Armed Forces before returning to Chechnya. A number of streets, squares and alleys in various countries are named after him, such as in Ukraine, Turkey, Poland, Estonia, Georgia, Lithuania and Latvia.

Early life and military career

Dudayev was born in Yalkhoroy from the Tsechoy teip in the Checheno-Ingush Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic (ASSR), just a few days before the forced deportation of his family together with the entire Chechen population on the orders of Joseph Stalin. He was the thirteenth youngest child of veterinarian Musa and Rabiat Dudayev. He spent the first 13 years of his life in internal exile in the Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic. His family was only able to return to Chechnya in 1957.[7] Following the 1957 repatriation of the Chechens, he studied at evening school in Checheno-Ingushetia and qualified as an electrician. In 1962, after two years studying electronics in Vladikavkaz, he entered the Tambov Higher Military Aviation School for Pilots from which he graduated in 1966. Dudayev joined the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in 1968 and from 1971 to 1974 studied at the prestigious Gagarin Air Force Academy. He married Alla, a Russian poet and the daughter of a Soviet officer, with whom he had three children (a daughter and two sons).[7]

In 1962, Dudayev began serving in the Soviet Air Force where he rose to the rank of Major-General, becoming its first Chechen general. Dudayev served in a strategic bombing unit of the Soviet Air Force in Siberia and Ukraine. He allegedly participated in the Soviet–Afghan War against the Mujahideen, for which he was awarded the Order of the Red Star and the Order of the Red Banner.[8] Reportedly from 1986 to 1987, Dudayev had participated in bombing raids in western Afghanistan. Many of his military and political opponents who questioned his Muslim faith often made reference to his actions against the Mujahideen forces.[9][10] For example, Sergei Stepashin asserted Dudayev participated in carpet bombing (a statement probably motivated by spite).[11][12] These allegations were denied by Dudayev himself.[13] Dudayev rose steadily in the Air Force, assuming command of the 326th Heavy Bomber Aviation Division of the Soviet Long Range Aviation at Tartu, Estonia, in 1987 gaining the rank of Major-General. From 1987 through March 1990, he commanded nuclear-armed long-range strategic bombers during his post there.[11][14][c]

He was also commander of the garrison of Tartu. He learned Estonian and showed great tolerance for restoration of Estonian independence when in autumn 1990 he ignored the orders (as commander of the garrison of Tartu) to shut down the Estonian television and parliament.[7][11] In 1990, his air division was withdrawn from Estonia and Dudayev resigned from the Soviet military.

Chechen politics

In May 1990, Dudayev returned to Grozny, the Chechen capital, to devote himself to local politics. He was elected head of the Executive Committee of the unofficial opposition All-National Congress of the Chechen People (NCChP), which advocated sovereignty for Chechnya as a separate republic of the Soviet Union (the Chechen-Ingush ASSR had the status of an autonomous republic of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic).

In August 1991, Doku Zavgayev, the Communist leader of the Chechen-Ingush ASSR, did not publicly condemn the August 1991 attempted coup d'état against Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev. Following the failure of the putsch, the Soviet Union began to disintegrate rapidly as the constituent republics took moves to leave the beleaguered Soviet Union. Taking advantage of the Soviet Union's implosion, Dudayev and his supporters acted against the Zavgayev administration. On 6 September 1991, the militants of the NCChP violently (the Grozny Communist party leader was killed and several other members were wounded) invaded a session of the local Supreme Soviet, effectively dissolving the government of the Chechen-Ingush ASSR. Grozny television station and other key government buildings were also taken over.[citation needed]

President of the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria

After a referendum in October 1991 confirmed Dudayev in his new position as president of the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria, he declared the republic's sovereignty and its independence from the Soviet Union. In November 1991, the then Russian President Boris Yeltsin dispatched troops to Grozny, but they were withdrawn when Dudayev's forces prevented them from leaving the airport. Russia refused to recognize the republic's independence, but hesitated to use further force against the separatists. From this point, the Checheno-Ingush Republic had become a de facto independent state.[citation needed]

Initially, Dudayev's government had diplomatic relations with Georgia where he received much moral support from the first Georgian President Zviad Gamsakhurdia. When Gamsakhurdia was overthrown in late 1991, he was given asylum in Chechnya and attended Dudayev's inauguration as President. While he resided in Grozny he also helped to organise the first "All-Caucasian Conference" which was attended by independentist groups from across the region. Ichkeria never received diplomatic recognition from any internationally recognised state other than Georgia in 1991.[citation needed]

The Chechen-Ingush Republic split in two in June 1992, amidst the increasing Ossetian-Ingush conflict. After Chechnya had announced its initial declaration of sovereignty in 1991, its former entity Ingushetia opted to join the Russian Federation as a federal subject (Republic of Ingushetia). The remaining rump state of Ichkeria (Chechnya) declared full independence in 1993. That same year the Russian language stopped being taught in Chechen schools and it was also announced that the Chechen language would start to be written using the Latin alphabet (with some additional special Chechen characters) rather than Cyrillic in use since the 1930s. The state also began to print its own money and stamps. One of Dudayev's first decrees gave every man the right to bear arms.[citation needed]

In 1993, the Chechen parliament attempted to organize a referendum on public confidence in Dudayev on the grounds that he had failed to consolidate Chechnya's independence. He retaliated by dissolving parliament and other organs of power. Beginning in early summer of 1994, armed Chechen opposition groups with Russian military and financial backing tried repeatedly but without success to depose Dudayev by force.[citation needed]

First Chechen War

On 1 December 1994, the Russians began bombing Grozny airport and destroyed some former Soviet training aircraft taken away by the republic in 1991. In response Ichkeria mobilised its armed forces. On 11 December 1994, five days after Dudayev and Minister of Defense Pavel Grachev of Russia had agreed to avoid the further use of force, Russian troops invaded Chechnya.[citation needed]

Before the fall of Grozny, Dudayev abandoned the presidential palace, moved south with his forces and continued leading the war throughout 1995, reportedly from a missile silo close to the historic Chechen capital of Vedeno. He continued to insist that his forces would prevail after the conventional warfare had finished, and the Chechen guerrilla fighters continued to operate across the entire republic. The full-scale Russian attack led many of Dudayev's opponents to side with his forces and thousands of volunteers to swell the ranks of mobile militant units.[citation needed]

Assassination

On 21 April 1996, while using a satellite phone, Dudayev was assassinated by two laser-guided missiles, after his location was detected by a Russian reconnaissance aircraft, which intercepted his phone call.[16] At the time, Dudayev was talking to Konstantin Borovoy, a deputy of the State Duma in Moscow.[17] Additional aircraft were dispatched (a Su-24MR and a Su-25) to locate Dudayev and fire a guided missile. Exact details of this operation were never released by the Russian government. Russian reconnaissance planes in the area had been monitoring satellite communications for some time trying to match Dudayev's voice signature to the existing samples of his speech. It was claimed Dudayev was killed by a combination of an airstrike and a booby trap. He was 52 years old.[18]

The death of Dudayev was announced on the interrupted television broadcast by Shamil Basayev, the Chechen guerrilla commander.[19] Dudayev was succeeded by his Vice-President Zelimkhan Yandarbiyev (as acting President) and then, after the 1997 popular elections, by his wartime Chief of Staff, Aslan Maskhadov.

Dudayev was survived by his wife, Alla, and their sons, Degi and Avlur.

Commemoration

There is a memorial plaque made of granite attached to the house on 8 Ülikooli street, Tartu, Estonia, in which Dudayev used to work.[20] The house now hosts Hotel Barclay, and the former office of Dudayev has been converted into Dudayev's Room.[21]

Places named in honor of Dudayev include:

Estonia – A large room in the Barclay Hotel in Tartu, once used as Dudaev's office, is now called the Dudaev Suite. Outside on the wall there is a Dudayev's Memorial plaque.

Estonia – A large room in the Barclay Hotel in Tartu, once used as Dudaev's office, is now called the Dudaev Suite. Outside on the wall there is a Dudayev's Memorial plaque. Georgia – There is a street in the Georgian capital Tbilisi named after Dzokhar Dudayev.[22]

Georgia – There is a street in the Georgian capital Tbilisi named after Dzokhar Dudayev.[22] Latvia – In 1996, a street in the Latvian capital Riga was named Džohara Dudajeva gatve (Dzhokhar Dudaev Street). In the light of the upcoming Parliamentary elections in Latvia, several initiatives have been undertaken to lobby for the renaming or preserving the name of the street by pro-Russian and anti-Russian political parties respectively.[23][24]

Latvia – In 1996, a street in the Latvian capital Riga was named Džohara Dudajeva gatve (Dzhokhar Dudaev Street). In the light of the upcoming Parliamentary elections in Latvia, several initiatives have been undertaken to lobby for the renaming or preserving the name of the street by pro-Russian and anti-Russian political parties respectively.[23][24] Lithuania – Džocharo Dudajevo skveras (Dzhokhar Dudaev Square) in the Žvėrynas district of Vilnius.[25]

Lithuania – Džocharo Dudajevo skveras (Dzhokhar Dudaev Square) in the Žvėrynas district of Vilnius.[25] Poland – On 17 March 2005, a roundabout in the Polish capital Warsaw was named Rondo Dżochara Dudajewa (Roundabout Dzhokhar Dudayev).[26]

Poland – On 17 March 2005, a roundabout in the Polish capital Warsaw was named Rondo Dżochara Dudajewa (Roundabout Dzhokhar Dudayev).[26] Turkey – After Dudayev's death, various locations in Turkey were renamed after him, such as Şehit Cahar Dudaev Caddesi (Martyr Dzhokhar Dudaev Street) and Şehit Cahar Dudayev Parki (Martyr Dzhokhar Dudayev Park) in Istanbul/Ataşehir-Örnek, Cahar Dudayev Meydanı (Dzhokhar Dudayev Square) in Ankara, Şehit Cahar Dudaev Parkı (Martyr Dzhokhar Dudaev Park) in Adapazarı, Sakarya and Şehit Cevher Dudaev Parkı in Sivas.[27]

Turkey – After Dudayev's death, various locations in Turkey were renamed after him, such as Şehit Cahar Dudaev Caddesi (Martyr Dzhokhar Dudaev Street) and Şehit Cahar Dudayev Parki (Martyr Dzhokhar Dudayev Park) in Istanbul/Ataşehir-Örnek, Cahar Dudayev Meydanı (Dzhokhar Dudayev Square) in Ankara, Şehit Cahar Dudaev Parkı (Martyr Dzhokhar Dudaev Park) in Adapazarı, Sakarya and Şehit Cevher Dudaev Parkı in Sivas.[27] Ukraine – In 1996, a street in Lviv was named вулиця Джохара Дудаєва (Dzhokhar Dudayev Street), later followed by a street in Ivano-Frankivsk[28][29] and a street in Khmelnytskyi.[30] In the war in Donbas, that started in the spring of 2014, a pro-Ukrainian volunteer battalion was named after Dudayev, led by former Chechen General Isa Munayev.[28] In December 2022 recently liberated (from Russian forces) Izium decided to rename Turgenev Street to Dzhokhar Dudayev Street.[31]

Ukraine – In 1996, a street in Lviv was named вулиця Джохара Дудаєва (Dzhokhar Dudayev Street), later followed by a street in Ivano-Frankivsk[28][29] and a street in Khmelnytskyi.[30] In the war in Donbas, that started in the spring of 2014, a pro-Ukrainian volunteer battalion was named after Dudayev, led by former Chechen General Isa Munayev.[28] In December 2022 recently liberated (from Russian forces) Izium decided to rename Turgenev Street to Dzhokhar Dudayev Street.[31]

-

Dzhokhar Dudayev Monument in Vilnius, Lithuania.

-

House number on Dzhokhar Dudayev avenue in Riga, Latvia.

-

Dzhokhar Dudayev Roundabout in Warsaw, Poland.

-

Dzhokhar Dudayev Street in Ivano-Frankivsk, Ukraine.

-

Dzhokhar Dudayev Square in Vilnius, Lithuania.

-

Chechen Gallery murals in Warsaw, Poland. Dzhokhar Dudayev on the left.

Notes

- ^ The spelling of Dudayev's given name in modern Chechen ranges between Джохар,[3] ДжовхӀар,[4] Джовхар,[5] and Жовхар.[6]

- ^ Chechen: Дудин Муса-воӏ Джохар, romanized: Dudin Musa-voj Dƶoxar,[a] [duˈdin muˈsɑvɔʕ d͡ʒɔwˈxɑr]; Russian: Джохар Мусаевич Дудаев;

- ^ While Dudayev was in Chechnya in the 1990s, his family lived at 21-52 Sõpruse Boulevard (Estonian: Sõpruse puiestee 21-52) which was his the residence while he commanded the 326th Heavy Bomber Aviation Division in Tartu.[15]

References

- 1994–1998 Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ "Конец мятежного генерала Джохара Дудаева". KM.RU Новости – новости дня, новости России, последние новости и комментарии.

- ^ Milyon Birinci – Cahar Dudayev (in Turkish)

- ^ "Бостонерчу полицино лаьцна Царнаев Джохар". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (in Chechen). 20 April 2013.

- ^ "Царнаев ДжовхIар вен цакхачор доьху адвокаташа". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (in Chechen). 9 May 2014.

- ^ "Царнаев Джовхаран гIуллакхерчу 13 документана тIера къайле дIаяьккхина прокуроран сацамца". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (in Chechen). 21 March 2013.

- ^ "Царнаев Жовхаран гIуллакхехь керла агIо йиллина". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty (in Chechen). 1 April 2014.

- ^ a b c Узел, Кавказский. "Дудаев Джохар Мусаевич". Кавказский Узел.

- ^ James Hughes, Chechnya: from nationalism to jihad p. 22

- ^ Christopher Marsh, Nikolas K. Gvosdev, Civil Society and the Search for Justice in Russia, p 148

- ^ John B. Dunlop, Russia Confronts Chechnya: Roots of a Separatist Conflict, p. 110

- ^ a b c John B. Dunlop, Russia Confronts Chechnya: Roots of a Separatist Conflict, p 111

- ^ Shireen T. Hunter (2004). Islam in Russia: The Politics of Identity and security (illustrated ed.). M.E. Sharpe. p. 150. ISBN 0-7656-1283-6.

- ^ Interview with Alla Dudaeva, Sobesednik.ru 2006 Archived 7 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Valeriĭ Aleksandrovich Tishkov (2004). Chechnya: Life in a War-Torn Society (illustrated ed.). University of California Press. p. 77. ISBN 0-520-23888-5. Retrieved 12 June 2011.

dudayev nuclear.

- ^ Karulin, Ott (8 October 2000). "Dudajevite võlg Tartus" [Dudayev debt in Tartu]. Õhtuleht (ohtuleht.ee) (in Estonian). Archived from the original on 22 December 2013. Retrieved 25 March 2022.

- ^ "TIME TO SET THE CHECHEN FREE". 5 April 2010. Archived from the original on 5 January 2012. Retrieved 4 October 2014.

- ^ Robert Young Pelton (2 March 2012). "Kill the messenger". Foreign Policy. Archived from the original on 16 August 2012.

- ^ 'Dual attack' killed president, BBC News, 21 April 1999

- ^ Chechen leader confirmed dead; Supporter says freedom fight unaffected CNN, 24 April 1996

- ^ "Džohhar Dudajevi mälestustahvel". info.raad.tartu.ee.

- ^ Postimees, 8 May 1996: "Nimeline tänav ja orden Dzhohhar Dudajevile" Archived 27 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "ვაკე-საბურთალოს რაიონი". www.cartogiraffe.com (in Georgian). Archived from the original on 11 April 2016. Retrieved 3 June 2015.

- ^ "Vāc parakstus Dudajeva gatves pārdēvēšanai". Apollo. 15 October 1925. Archived from the original on 29 September 2009. Retrieved 30 December 2012.

- ^ "Paraksties par Džohara Dudajeva gatves nosaukuma saglabāšanu". Kristaps Skutelis. 23 November 2009. Archived from the original on 28 November 2009. Retrieved 30 December 2012.

- ^ "Wikimapia – Let's describe the whole world!".

- ^ Warsaw's Dudaev move irks Moscow BBC News, 21 March 2005

- ^ "Kocasinan Dudayev Parkı yenileniyor" [Kocasinan Dudayev Park is being renovated]. www.kayserigundem.com (in Turkish). 29 November 2006. Archived from the original on 24 December 2007.

- ^ a b Chechen fighter transfers struggle against Kremlin to Ukraine, Chechen fighter transfers struggle against Kremlin to Ukraine], Kyiv Post (27 May 2014)

- ^ Головатий М. 200 вулиць Івано-Франківська. — Івано-Франківськ: Лілея-НВ, 2010. — С. 144—145

- ^ Як у Хмельницькому Джохара Дудаєва вшановували at khm.depo.ua (ukrainian)

- ^ "Bandera Street appeared in the liberated Izium". Ukrayinska Pravda (in Ukrainian). 3 December 2022. Retrieved 3 December 2022.

Sources

- Khaustov, V. N. (2007). "ДУДА́ЕВ ДЖОХАР МУСАЕВИЧ" [DUDÁYEV DZHOKHAR MUSAYEVICH]. In Kravets, S. L.; et al. (eds.). Great Russian Encyclopedia (in Russian). Vol. 9: Dinamika atmosfery - Zheleznodorozhny uzel. Moscow: Great Russian Encyclopedia. ISBN 978-5-85270-339-2.

External links

Media related to Dzhokhar Dudayev at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Dzhokhar Dudayev at Wikimedia Commons

See also

- Russism, his description of the state ideology of the Russian Federation, which he made during the First Chechen War. Since then many scholars, publicists, politicians have built upon his concept.

- 1944 births

- 1996 deaths

- Assassinated Chechen politicians

- Deaths by airstrike

- Chechen field commanders

- Chechen guerrillas killed in action

- Chechen nationalists

- Chechen anti-communists

- Communist Party of the Soviet Union members

- People of the Chechen wars

- Politicians of Ichkeria

- Heads of the Chechen Republic

- Soviet Air Force generals

- Soviet major generals

- Soviet military personnel of the Soviet–Afghan War

- Chechen independence activists

- Heads of state of former countries

- Recipients of the Order of the Red Star

- Recipients of the Order of the Red Banner

- North Caucasian independence activists

- Estonian nationalists

- Estonian anti-communists

- 1990s assassinated politicians