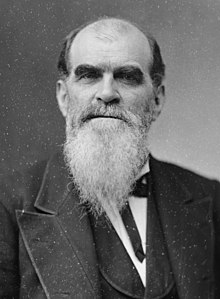

Richard Coke

Richard Coke | |

|---|---|

| |

| United States Senator from Texas | |

| In office March 4, 1877 – March 3, 1895 | |

| Preceded by | Morgan C. Hamilton |

| Succeeded by | Horace Chilton |

| 15th Governor of Texas | |

| In office January 15, 1874 – December 1, 1876 | |

| Lieutenant | Vacant |

| Preceded by | Edmund J. Davis |

| Succeeded by | Richard B. Hubbard |

| Personal details | |

| Born | March 18, 1829 Williamsburg, Virginia, U.S. |

| Died | May 14, 1897 (aged 68) Waco, Texas, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Alma mater | College of William and Mary (LLB) |

Richard Coke (March 18, 1829 – May 14, 1897) was an American lawyer and statesman from Waco, Texas. He was the 15th governor of Texas from 1874 to 1876 and was a US Senator from 1877 to 1895. His governorship is notable for reestablishing local white supremacist rule in Texas following Reconstruction. Richard Coke was revered by many Texas Southern Democrats due to his perceived triumphs over Reconstruction era Federal control in Texas politics.[1] His legacy is also marked by his use of the newly established state power to disfranchise African American voters and institute White Supremacist policies.[2] His uncle was US Representative Richard Coke Jr.

Early life and education

Richard Coke was born in 1829 in Williamsburg, Virginia, to John and Eliza (Hankins) Coke. Octavius Coke was his brother. He graduated from the College of William and Mary in 1848 with a law degree.[3]

Confederacy and Early Career

In 1850, Coke moved to Texas and opened a law practice in Waco. In 1852, he married Mary Horne of Waco. The couple had four children, but all of them died before age 30.

In 1859, Coke was appointed by governor Hardin R. Runnels to lead a commission tasked with removing the remaining Comanche natives from West Texas and the Texas Hill Country.[1]

Coke was a delegate to the Secession Convention at Austin in 1861. The convention's chief concern was keeping slavery legal.[4] Coke owned slaves himself.[5] He voted that Texas should leave the United States to join the Confederacy.[2]

He joined the Confederate Army as a private.[6] In 1862, he raised a company that became part of the 15th Texas Infantry and served as its captain for the rest of the war. He was wounded in an action known as Bayou Bourbeau on November 3, 1863, near Opelousas, Louisiana. After the war, he returned home to Waco.

Reconstruction

In 1865, Coke was appointed a Texas district court judge, and in 1866, he was elected as an associate justice to the Texas Supreme Court. The following year, the military Governor-General Philip Sheridan removed Coke and four other judges as ‘an impediment to reconstruction’, in pursuit of unionist Reconstruction policies.[6] The removal of the five judges became a cause célèbre and made their names famous, synonymous in the public eye with resistance to Union occupation.

Richard Coke leveraged resentment at Union occupation to construct a Democratic electoral coalition that ruled Texas for more than 100 years. Through Ku Klux Klan attacks, intimidation, and public lynching of Black voters and their white allies, Coke's coalition re-established conservative white control of Texas in the 1870s.[7] Disfranchisement of Black Texans was maintained with poll taxes and white primaries. The number of black voters decreased sharply from more than 100,000 in the 1890s to 5,000 in 1906.[8]

Having been removed by Sheridan, Coke ran for governor as a Democrat in 1873 and took office in January 1874. The Texas Supreme Court ruled his election invalid in an extraordinary habeas corpus writ called Ex Parte Rodriguez because the polls were open for only one day, rather than the four days mentioned in the state constitution. The court is known as the "Semicolon Court" because the meaning of a particular semicolon in the constitution was important in the case.[9] As recounted by the Texas State Historical Association, in response,

Disregarding the court ruling, the Democrats secured the keys to the second floor of the Capitol and took possession. [Incumbent Gov. Edmund] Davis was reported to have state troops stationed on the lower floor. The Travis Rifles (a Texas military unit created to fight Indians), summoned to protect Davis, were converted into a sheriff's posse and protected Coke. On January 15, 1874, Coke was inaugurated as governor. On January 16, Davis arranged for a truce, but he made one final appeal for federal intervention. A telegram from President Ulysses S. Grant said that he did not feel warranted in sending federal troops to keep Davis in office. Davis resigned his office on January 19. Coke's inauguration restored Democratic control in Texas.[10]

Coke's administration was marked by vigorous action to balance the budget and by a revised state constitution adopted in 1876. He was also instrumental in creating the Agricultural and Mechanical College of Texas, which became Texas A&M University. Having once been removed from the Texas Supreme Court, as governor, he appointed all its members, naming as Chief Justice Oran Roberts (after the US Senate had refused to seat him). George F. Moore, who was Chief Justice when he had been fired along with Coke, became the first chief justice elected under Texas' 1876 Constitution, an honor he held until his death. Others from the Texas judiciary under the Confederacy received key appointments.

Once the new Constitution had been negotiated, Coke resigned his office in December 1876, following his election by the legislature to the United States Senate.

Later life and death

Coke was re-elected to federal office in 1882 and 1888, serving in the 45th – 53rd Congresses until March 3, 1895.[6] Coke was not a candidate for reelection in 1894.

Coke retired to his home in Waco and his nearby farm. He became ill after suffering exposure while fighting a flood of the Brazos River in April 1897. After a short illness, he died at his home in Waco and was buried in Oakwood Cemetery.

Legacy

Coke's rise to power marked the return of locally elected government in Texas and the establishment of a rigidly white supremacist Texas Democratic party that would maintain a strong hold on Texas government for over 100 years. Historians in the state praised Davis for this, and consolidated a version of Texas history that downplayed or omitted the liberal government that had preceded him.[2] In 1916 the state archivist wrote:

Governor Coke had faith in his people. He believed in the supremacy of the Anglo-Saxon race—he prided himself in the rich blood of the Southern people. As their leader he fought back the tide of tyranny that was about to engulf them in the murky water of mulatto domination. He was a constructive statesman; he served his people with true fidelity and left Texas to rich heritage of a fruitful and useful like. His name is engraved on the scroll of immortals, and his footprints are in the sands of time.

— Sinclair Moreland, Texas state archivist (1916)[2]

The 1876 constitution created under Coke's administration is the current Constitution of Texas. Coke County in West Texas is named for him. Texas Governor Coke Stevenson was named after Richard Coke.[11]

References

- Biography of Richard Coke from The Biographical Encyclopedia of Texas, hosted by the Portal to Texas History.

- ^ a b "TSHA | Coke, Richard".

- ^ a b c d Minutaglio, Bill (2021). A Single Star and Bloody Knuckles: A History of Politics and Race in Texas. University of Texas Press. pp. 31–33. ISBN 9781477310366.

- ^ "1. Richard Coke". Retrieved November 20, 2023.

- ^ "Richard Coke (1829–1897)". Tarlton Law Library. University of Texas. Retrieved July 8, 2021.

- ^ "Congress slaveowners", The Washington Post, January 19, 2022, retrieved July 15, 2022

- ^ a b c http://bioguide.congress.gov/scripts/biodisplay.pl?index=C000601 US Congressional bioguide

- ^ Carrigan, William D. (2004). The Making of a Lynching Culture: Violence and Vigilantism in Central Texas, 1836–1916. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press. pp. 138–139. ISBN 978-0-252-07430-1.

- ^ African-American Pioneers of Texas: From the Old West to the New Frontiers (Teacher's Manual) (PDF). Museum of Texas Tech University: Education Division. p. 25. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 5, 2007.

- ^ "TSHA | Semicolon Court". www.tshaonline.org. Retrieved September 14, 2021.

- ^ "TSHA | Coke-Davis Controversy". www.tshaonline.org. Retrieved September 14, 2021.

- ^ Caro, Robert A. (1990). "The Story of Coke Stevenson". Means of Ascent. The Years of Lyndon Johnson. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. pp. 145–178. ISBN 0-394-52835-2.

External links

- Sketch of Richard Coke from A pictorial history of Texas, from the earliest visits of European adventurers, to A.D. 1879, hosted by the Portal to Texas History.

- United States Congress. "Richard Coke (id: C000601)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- Richard Coke at Find a Grave

- Habeas writs that helped define Reconstruction-era Texas, Grits for Breakfast, December 15, 2012.

- 1829 births

- 1897 deaths

- Politicians from Williamsburg, Virginia

- American people of English descent

- Democratic Party United States senators from Texas

- Democratic Party governors of Texas

- Governors of Texas

- Justices of the Texas Supreme Court

- American white supremacists

- Texas lawyers

- 19th-century American politicians

- William & Mary Law School alumni

- Confederate States Army officers

- People of Texas in the American Civil War

- Burials at Oakwood Cemetery (Waco, Texas)

- United States senators who owned slaves