Battle of Duck Lake

52°49′27.19″N 106°16′25.98″W / 52.8242194°N 106.2738833°W

| Battle of Duck Lake | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the North-West Rebellion | |||||||

This contemporary illustration of the Battle of Duck Lake offers a romanticized depiction of the skirmish. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Provisional Government of Saskatchewan (Métis) |

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Gabriel Dumont | Leif Crozier | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 200–250[1] | 95[1] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

5–6 dead[1][2] 3 wounded[1] |

12 dead[1][3] 12 wounded[1][3] | ||||||

| Official name | Battle of Duck Lake National Historic Site of Canada | ||||||

| Designated | 1924 | ||||||

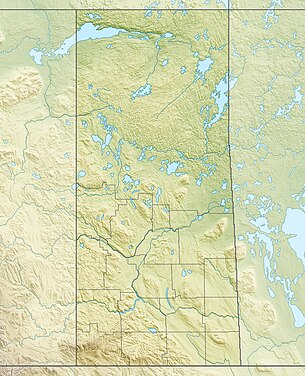

The Métis conflict area is circled in black.

The Battle of Duck Lake (26 March 1885) was an infantry skirmish 2.5 kilometres (1.6 mi) outside Duck Lake, Saskatchewan, between North-West Mounted Police forces of the Government of Canada, and the Métis militia of Louis Riel's newly established Provisional Government of Saskatchewan.[4] The skirmish lasted approximately 30 minutes, after which Superintendent Leif Newry Fitzroy Crozier of the NWMP, his forces having endured fierce fire with twelve killed and eleven wounded, called for a general retreat.[5] The battle is considered the initial engagement of the North-West Rebellion.[6] Although Louis Riel proved to be victorious at Duck Lake, the general agreement among historians is that the battle was strategically a disappointment to his cause.[citation needed]

Prelude

On March 19, 1885, Louis Riel self-affirmed the existence of the new Provisional Government of Saskatchewan.[7] Following Riel's declaration, the Canadian government sought to reassert their control over the turbulent territory. Leif Crozier, the newly appointed NWMP superintendent and commander of North-Western Saskatchewan's forces, requested immediate reinforcement to Fort Carlton because he feared the growing instability created by Riel and the ever-growing possibility of a First Nations uprising.[8] Riel dispatched emissaries to deliver an ultimatum calling for the surrender of Fort Carlton without bloodshed. Crozier's representatives rejected the demand and vowed that the Métis leaders would be brought to justice.[9]

On March 25, in need of supplies for his men and horses, Crozier ordered Sergeant Alfred Stewart, Thomas McKay, and seventeen constables to Hillyard Mitchell's general goods store at Duck Lake.[10] Unbeknownst to Crozier, however, commander Gabriel Dumont (Riel's right-hand man) and his Métis force had already entrenched themselves on the road to Duck Lake. On the morning of the 26th, Stewart's party encountered the band of Métis near Duck Lake. After ample harassment, Stewart decided not to risk a physical engagement, and chose to return to Fort Carlton; no shooting occurred.[11] Crozier rallied together a larger force, which included 53 North-West Mounted Police non-commissioned officers and men, 41 men of the Prince Albert Volunteers, and a 7-pound cannon, and set out to secure the much-needed supplies and to reassert the authority of the Canadian government in the District of Saskatchewan.[12]

Battle

The forces met about 2.5 kilometres (1.6 mi) outside Duck Lake on a snowy plateau covered by trees, shrubs, and a few log cabins.[12] Having spotted Crozier's force, Gabriel Dumont ordered his men to set up defensive positions around the log cabin and lie in wait. Similarly, Crozier's scouts informed the superintendent of the movements of the Métis; subsequently, Crozier ordered his men to halt and deploy their sleighs parallel to the road which was just before them. Both sides took up defensive positions.[12]

Gabriel Dumont dispatched his brother, Isidore, and an elderly half-blind chief, Assiwiyin, with a white flag in hopes of distracting Crozier's forces.[13] The superintendent, believing that Dumont was interested in a parley, walked forward with an English Métis interpreter, "Gentleman" Joe McKay.[14][15] During the half-hearted discussion, Crozier came to believe that Isidore and Assiwiyin were stalling so that the Métis force could manoeuver to flank his own men. As they began to leave, both Assiwiyin and Isidore attempted to draw their guns, prompting Crozier to give McKay the order to fire. A brief scuffle ensued between the two parties, which resulted in McKay shooting, and killing, both Isidore and Assiwyin.[14][15]

Despite the firepower and training of Crozier's militia, the Métis force were more numerous and their position within the log cabins and the tree line proved to be an efficient advantage.[16] In an attempt to relieve the pressure on the Prince Albert Volunteers, Crozier ordered the 7-pound cannon to target the log cabins. After numerous discharges, a shell was placed in before the power charge was inserted, which disabled the cannon for the remainder of the battle.[17]

Within half an hour, Crozier recognized the unavoidable and sounded a general retreat back to Fort Carlton. The Métis were eager to chase down Crozier and his retreating force, but Louis Riel intervened and declared the battle over.[17]

Aftermath

The battle toll was high for the government forces. Twelve men were killed, and eleven men seriously injured.[17] For the opposing side, five Métis warriors were killed in the skirmish, including Dumont's brother. Furthermore, Gabriel Dumont himself was injured in the head by a passing bullet.[18] Losing to Riel and the Métis force came as a great shock to Crozier's superiors. Colonel Acheson Irvine, Crozier's supervisor, suggested that Crozier's officerial prowess and judgement was overruled by impulsiveness.[19]

Fort Carlton, a trading post with few defensive installations, was now in serious risk of attack. Immediately, Colonel Irvine summoned a council to discuss the future of Fort Carlton. The resounding unanimous decision was in favour of the evacuation and destruction of the fort.[20] By 4 AM on 28 March, the last sleigh had left the smouldering fort.[21]

In the span of three days and with the loss of only five men, Riel's forces had defeated Crozier's militia, forced the destruction and scavenged the remains of Fort Carlton, and spread fear of a Métis uprising throughout the North-West Territories. Riel's plans were not completely successful, though: he had hoped to capture Crozier and his men as hostages so that he might force the government's hand. Thus, while tactically successful, the battle of Duck Lake proved to be a strategic disappointment for Riel.[22]

Legacy

"Duck Lake Battlefield—Here, on 26th March 1885, occurred the first combat between the Canadian Government Forces, under Major L.N.F. Crozier, and the Metis and Indians, under Gabriel Dumont. Ici, le 26 mars, 1885, eut lieu la première rencontre entre les troupes du gouvernement du Canada, commandées par le Major Crozier, et les Métis et Indiens commandés par Gabriel Dumont."

National Historic Sites and Monuments Board[23]

The site of the battle was designated a National Historic Site of Canada in 1924.[24]

In the spring of 2008, Tourism, Parks, Culture and Sport Minister Christine Tell proclaimed in Duck lake, that "the 125th commemoration, in 2010, of the 1885 Northwest Resistance is an excellent opportunity to tell the story of the prairie Métis and First Nations peoples' struggle with Government forces and how it has shaped Canada today."[25]

Duck Lake is home to the Duck Lake Historical Museum and the Duck Lake Regional Interpretive Centre, and murals which reflect the history of the rebellion in the area. The Battle of Duck Lake, the Duck Lake Massacre, and a buffalo jump are all located here. The "First Shots Cairn" was erected on Saskatchewan Highway 212 as a landmark commemorating the scene of the first shots in the Battle of Duck Lake. The Our Lady of Lourdes Shrine at St. Laurent north of Duck Lake is a local pilgrimage site.[26][27][28][29]

See also

- List of battles won by Indigenous peoples of the Americas

- North-West Rebellion

- Provisional Government of Saskatchewan

- Prince Albert Volunteers

- North-West Mounted Police

References

- ^ a b c d e f Mulvaney, Charles Pelham (1886). The History of the North-west Rebellion of 1885: Comprising a Full and Impartial Account of the Origin and Progress of the War, Scenes in the Field, the Camp, and the Cabin; Including a History of the Indian Tribes of North-western Canada. Toronto: A.H. Hovey & Co. p. 32. Retrieved 2014-04-10.

- ^ Barkwell, Lawrence J. (3 March 2010). "Heroes of the 1885 Northwest Resistance. Summary of those Killed". Louis Riel Institute. Retrieved 2013-11-13.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ a b Panet, Charles Eugène (1886). Report upon the suppression of the rebellion in the North-West Territories and matters in connection therewith, in 1885: Presented to Parliament. Ottawa: Department of Militia and Defence. p. xi. Retrieved 2014-04-10.

- ^ Morton (1972), p. 4.

- ^ Morton (1972), p. 5.

- ^ Barkwell, Lawrence J. (2011). Veterans and Families of the 1885 Northwest Resistance. Saskatoon: Gabriel Dumont Institute. ISBN 978-1-926795-03-4.[page needed]

- ^ Morton (1972), p. XXII.

- ^ Wallace (1998), p. 63.

- ^ Wallace (1998), p. 69.

- ^ Haydon (1971), p. 130.

- ^ Stanley, George F. G. (1963). Louis Riel. Toronto: The Ryerson Press. p. 315.

- ^ a b c Stanley (1960), p. 326.

- ^ "The Battle of Duck Lake (March 26, 1885)" (PDF). Back to Batoche. Gabriel Dumont Institute. Retrieved 3 December 2013.

- ^ a b Wallace (1998), p. 74.

- ^ a b "How the Battle of Duck Lake Began: Two Perspectives" (PDF). Back to Batoche. Gabriel Dumont Institute. Retrieved 3 December 2013.

- ^ Stanley. Louis Riel. p. 317.

- ^ a b c Stanley (1960), p. 328.

- ^ Stanley. Louis Riel. p. 318.

- ^ Stanley (1960), p. 329.

- ^ Haydon (1971), p. 133.

- ^ Stanley (1960), p. 330.

- ^ Stanley (1960), p. 332.

- ^ "Duck Lake Battlefield Plaque". The Virtual Museum of Métis History and Culture. Gabriel Dumont Institute. Retrieved 20 September 2009.

- ^ Battle of Duck Lake. Canadian Register of Historic Places. Retrieved 6 August 2012.

- ^ "Tourism agencies to celebrate the 125th anniversary of the Northwest Resistance/Rebellion" (Press release). Government of Saskatchewan. 7 June 2008. Archived from the original on 21 October 2009. Retrieved 20 September 2009.

- ^ "History of Duck Lake and Area". Duck Lake Regional Interpretive Centre. Archived from the original on 20 August 2008. Retrieved 20 September 2009.

- ^ "Attractions and Tourism: Town of Duck Lake, Saskatchewan". M.R. Internet. Town of Duck Lake. 2007. Archived from the original on 2009-12-13. Retrieved 2009-09-20.

- ^ McLennan, David (2006). "Duck Lake: The Encyclopedia of Saskatchewan". Canadian Plains Research Center University of Regina. Archived from the original on 2012-11-06. Retrieved 2009-09-20.

- ^ "Battleford, Batoche & Beyond Tour along the Yellowhead Highway". Yellowhead It! Travel Magazine. Yellowhead Highway Association. Retrieved 2009-09-20.

- Sources

- Haydon, A.L. (1971) [1910]. The Riders of the Plains: a Record of the Royal North-West Mounted Police of Canada, 1873-1910. Edmonton: M.G Hurting.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) – 1910 edition; The Riders of the Plains at the Internet Archive - Morton, Desmond (1972). The Last War Drum: The North West Campaign of 1885. Canadian War Museum. Vol. Volume 5. Hakkert.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Stanley, George F.G. (1960). The Birth of Western Canada: a History of the Riel Rebellions (2nd ed.). University of Toronto Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) – First Edition (1936) available at University of Alberta Library - Wallace, Jim (1998). A Trying Time: the North-West Mounted Police in the 1885 Rebellion. Bunker to Bunker Books. ISBN 978-1-894255-00-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Further reading

- Beal, Bob (4 March 2015). Battle of Duck Lake (online ed.). Historica Canada.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|work=ignored (help) - Beal, Bob; Macleod, Rod (22 February 2019). North-West Rebellion (online ed.). Historica Canada.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|work=ignored (help) - The Story of Saskatchewan and its people Volume 1 (Duck Lake)[permanent dead link]