Narsinh Mehta

This article may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. The specific problem is: Italicize other titles in Gujarati language. (March 2013) |

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2018) |

Narsinh Mehta | |

|---|---|

| Born | Early 15th century |

| Died | Late 15th century |

| Notes | |

No consensus on dates among scholars except living in 15th century | |

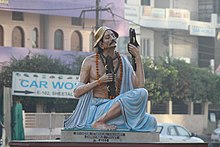

Narsinh Mehta, also known as Narsi Mehta or Narsi Bhagat , was a 15th-century poet-saint of Gujarat, India, notable as a bhakta, an exponent of Vaishnava poetry. He is especially revered in Gujarati literature, where he is acclaimed as its Adi Kavi (Sanskrit for "first among poets"). His bhajan Vaishnav Jan To was Mahatma Gandhi's favourite and has become synonymous with him.[1]

Biography per traditional sources

Narsinh Mehta was born in a Nagar Brahmin family at Talaja and later moved to Junagadh in Saurashtra peninsula of modern-day Gujarat. His father held an administrative post in a royal court. He lost his parents when he was five years old. He could not speak until the age of eight. He was raised by his grandmother Jaygauri.[2][3]

He married Manekbai probably in the year 1429. Mehta and his wife stayed at his brother Bansidhar's house in Junagadh. However, Bansidhar's wife (Sister-in-law or bhabhi) did not welcome Narsinh very well. She was an ill-tempered woman, always taunting and insulting Narsinh Mehta for his devotion (Bhakti). One day, when Narasinh Mehta had enough of these taunts and insults, he left the house and went to a nearby forest in search of some peace, where he fasted and meditated for seven days by a secluded Shiva lingam until Shiva appeared before him in person. On the poet's request, the Lord took him to Vrindavan and showed him the eternal raas leela of Krishna and the Gopis. A legend has it that the poet, transfixed by the spectacle, burnt his hand with the torch he was holding, but he was so engrossed in the ecstatic vision that he was oblivious to the pain. Mehta, as the popular account goes, at Krishna's command, decided to sing His praises and the nectarous experience of the rasa in this mortal world. He resolved to compose around 22,000 kirtans or compositions.[1]

After this divine experience, the transformed Mehta returned to his village, touched his sister-in-law's feet as reverence, and thanked her for insulting him for had she not made him upset, the above episode would not have occurred.

In Junagadh, Mehta lived in poverty with his wife and two children, a son named Shamaldas, and a daughter for whom he had special affection, Kunwarbai. He revelled in devotion to his heart's content along with sadhus, saints, and all those people who were Lord Hari's subjects – Harijans – irrespective of their caste, class or sex. It also seems that he must have fallen into a somewhat ill repute amongst the Nagars following incidents like accepting invitation to sing glories of Lord Krishna in association of devotees belonging to lower social strata. The Nagars of Junagadh despised him and spared no opportunity to scorn and insult him [citation needed]. By this time, Mehta had already sung about the rasaleela of Radha and Krishna. The compositions are collected under the category of Shringar compositions. They are full of intense lyricism, based upon pastimes of conjugal love between the Supreme Lord and His most intimate devotees - the Gopis and are not without allegorical dimensions.[1]

Soon after his daughter, Kunwarbai's marriage (around 1447) to Shrirang Mehta of Una's son, Kunwarbai conceived and it had been a custom for the girl's parents to give gifts and presents to all the in-laws during the seventh month of pregnancy. This custom, known as Mameru, was simply out of the reach of materialistically poor Narsinh who had hardly anything except intransient faith in his Lord. How Krishna helped his beloved devotee is a legend depicted in 'Mameru Na Pada'. This episode is preserved vividly in the memory of Gujarati people by compositions by later poets and films. Other famous legends include: 'Hundi (Bond)' episode and 'Har Mala (Garland)' episode. The episode in which none other than Shamalsha Seth cleared a bond written by poverty-stricken beloved, is famous not only in Gujarat but in other parts of India as well. The Har Mala episode deals with the challenge given to Mehta by Ra Mandalika (1451–1472), a Chudasama king, to prove his innocence in the charges of immoral behaviour by making the Lord Himself garland Narsinh. Mehta depicts this episode. How Sri Krishna, in the guise of a wealthy merchant, helped Mehta in getting his son married is sung by the poet in Putra Vivah Na Pada. He went to Mangrol where, at the age of 79, he is believed to have died. The crematorium at Mangrol is called 'Narsinh Nu Samshan' where one of the sons of Gujarat and more importantly a great Vaishnav was cremated. He will forever be remembered for his poetic works and devotion to Lord Krishna. He is known as the first poet of Gujarati Adi Kavi.[1]

Study of biography

Darshana Dholakiya had studied the development of biography of Narsinh Mehta. She has divided the development in three stages; biography from his poetry which is autobiographical in nature, biography emerging from poetry of poets born between Krishnadas and Premanand, biography written by poets after Premanand. She considers second stage very important because an image of Narsinh Mehta's personality was established during this period.[4]

Time

No year is mentioned in his compositions. So there is difference of opinions among scholars about his time.[4]

The mention of Junagadh king Mandalika is considered to establish his date. No independent poem of the event of garland is found in the biographical poems of the poets of second period like Krishnadas, Vishnudas, Govind, Vishwanath Jani or Premanand but the event of garland is mentioned in some poems.[4]

A poem on the event of garland is independently found in the autobiographical poems said to be composed by Narsinh. The oldest manuscript dated Samvat 1675 has seven poems (pada) which also mentions Mandalika. So it can be said that the contemporaneity of Mandalika and Narsinh was established by Samvat 1675. One poem on the event of garland even mentions Samvat 1512 as the date of event but the authenticity is not established. So it is known that the contemporaneity of Mandalika and Narsinh is popular in old as well as new traditions. One question emerge from that why did Mandalika tested him even though he was mentioned as a religious Vaishnava in other sources. This Mandalika must have been Mandalika III (r. 1451 – 1472 CE or Samvat 1506–1527) and was defeated by Mahmud Begada. His defeat is connected to the test of Narsinh. Other reasons for his defeat mentioned are the curse of Charan lady Nagbai and his relation with wife of his minister Vishal.[4]

Clan and pedigree

In older traditions, there is no mention of his clan. Names of his parents or brother is not mentioned either.[4]

Narsain Mehtanu Akhyan (written after Samvat 1705) mentions one Parvat Mehta but he was not related to Narsinh Mehta and he is just mentioned as a devotee.[4]

Vallabhdas' Shamaldasno Vivah gives information about his clan and ancestry. Purushottam is mentioned as his grandfather. His gotra is Kashyap. His Veda division and his family deities (Kuladevta and Kuladevi) is also mentioned. The following family tree is mentioned in it:[4]

- Purushottam

- Parvatdas

- Narbat

- Haridas

- Ram

- Krishnadas

- Narsinh

- Jivan

- Narbheram

- Parvatdas

Draupadi Pattavidhan composed by Rangildas, son of Trikamdas, mentions that Trikamdas was mentioned in Narsinh's clan. But it can be taken as the common Nagar clan.[4]

Several pedigrees are recorded later but they differ from each other. One pedigree even mentions Narsinh as an uncle of Parvatdas though Parvatdas is commonly mentioned as an uncle of Narsinh. So authenticity of these pedigrees are questionable. Vallabhdas' Shamaldas no Vivah has years of Narsinh arranged so it seems that he had tried to establish his biography.[4]

So Dholakiya opines that the authentic pedigree of Narsinh Mehta has not survived.[4]

Place of worshiped Shivalinga

The exact location of the non-reverend Shivalinga worshiped by Narsinh is not mentioned in old as well as new traditions.[4]

Shamaldas No Vivah, purportedly composed by Narsinh himself, mentions the place as Gopinath. Later work Narsain Mehtanu Akhyan mentions it as Gopeshwar. Some scholars mentions Gopnath near Talaja as the place but it is dubious because Narsinh had worshiped it in forest while the Gopnath is on the seashore. It must have been near Junagadh because mention of forest.[4]

Family tradition

As he worshiped Shiva after leaving home, it can be said that his family tradition was Shaivism. He became Vaishnava due to Shiva. It is mentioned that other Nagars opposed him due to his Vaishnava tradition. Vishwanath Jani's Mosalacharitra mentions that a Nagar opposed him saying that he is not vipra (Brahmin) because he is Vaishnava. So Dholakiya opines that the event of Shiva may have originated to make his Vaishnava devotion acceptable.[4]

Harivallabh Bhayani opines that the Vaishnava devotion was prevalent in Narshin's time and it is not unusual that he was devotee of Vaishnava. He also mentions the Vaishnava surname among Nagars.[4]

Education and profession

No education or profession other than religious devotion is mentioned in his poetry. It is said that he became poet due to grace of god but Bhayani opines that, if we consider Chaturi as his full or partial composition, its language, style and emotion establishes Narsinh's knowledge of literary traditions and creativity. Narsinh must have known Geet Govind, Vedant etc. It works seem influenced by Marathi poets like Namdev. So he must have studied according to his Nagar family tradition.[4]

Society and Narsinh

Narsinh was opposed in his Nagar society but the opposition was not strong as much seen in other saint-poets like Meera and Kabir of that era. The reasons behind opposition seem his acceptance of Vaishnava tradition even though his family tradition was Shaiva, his attitude towards society and poor and his friendly devotion to god in view of orthodox society. His life events matches events of several popular saint-poets like Surdas, Tulsidas, Meera, Kabir, Namdev and Sundarar. While several saint-poets are not involved in household, Narsinh was involved in household even after his commitment to devotion. He lived with his family and he did not had any followers.[4]

Works

Mehta is a pioneer poet of Gujarati literature. He is known for his literary forms called "pada (verse)", "Akhyana" and "Prabhatiya" (morning devotional songs). One of the most important features of Mehta's works is that they are not available in the language in which Narsinh had composed them. They have been largely preserved orally. The oldest available manuscript of his work is dated around 1612, and was found by the noted scholar Keshavram Kashiram Shastri from Gujarat Vidhya Sabha. Because of the immense popularity of his works, their language has undergone modifications with changing times. Mehta wrote many bhajans and Aartis for lord Krishna, and they are published in many books. The biography of Mehta is also available at Geeta Press.

For the sake of convenience, the works of Mehta are divided into three categories:

- Autobiographical compositions: Putra Vivah/Shamaldas no Vivah, Mameru/Kunvarbai nu Mameru, Hundi, Har Mala, Jhari Na Pada, and compositions depicting acceptance of Harijans. These works deal with the incidents from the poet’s life and reveal how he encountered the divine in various guises. They consist of 'miracles' showing how god helped his devotee Narsinh in the time of crises.[4]

- Miscellaneous Narratives: Chaturis, Sudama Charit, Dana Leela, and episodes based on Srimad Bhagwatam. These are the earliest examples of akhyana or narrative type of compositions found in Gujarati. These include:

- Chaturis, 52 compositions resembling Jaydeva’s masterpiece Geeta Govinda dealing with various erotic exploits of Radha and Krishna.

- Dana Leela poems dealing with the episodes of Krishna collecting his dues (dana is toll, tax or dues) from Gopis who were going to sell buttermilk etc. to Mathura.

- Sudama Charit is a narrative describing the well-known story of Krishna and Sudama.

- Govinda Gamana or the "Departure of Govind" relates the episode of Akrura taking away Krishna from Gokul.

- Surata Sangrama, The Battle of Love, depicts in terms of a battle the amorous play between Radha and her girl friends on the one side and Krishna and his friends on the other.

- Miscellaneous episodes from Bhagwatam like the birth of Krishna, his childhood pranks and adventures.

- Songs of Sringar. These are hundreds of padas dealing with the erotic adventures and the amorous exploits of Radha and Krishna like Ras Leela. Various clusters of padas like Rasasahasrapadi and Sringar Mala fall under this head. Their dominant note is erotic (Sringar). They deal with stock erotic situations like the ossified Nayaka-Nayika Bheda of classical Sanskrit Kavya poetics.[1]

See: Vaishnav jan to, his popular composition.

In popular culture

The first Gujarati talkie film, Narsinh Mehta (1932) directed by Nanubhai Vakil was based on Narsinh Mehta's life.[5] It was devoid of any miracles due to Gandhian influence. The bilingual film Narsi Mehta in Hindi and Narsi Bhagat in Gujarati (1940) directed by Vijay Bhatt included miracles and had paralleled Mehta with Mahatma Gandhi. Narsaiyo (1991) was a Gujarati television series telecast by the Ahmedabad centre of Doordarshan starring Darshan Jariwala in lead role. This 27-episode successful series was produced by Nandubhai Shah and directed by Mulraj Rajda.[3]

Further reading

Works of Narsinh Mehta

- Narsinh Mehta. Narsinh Mehtani Kavyakrutiyo (ed.). Shivlal Jesalpura. Ahmedabad: Sahitya Sanshodhan Prakashan, 1989

- Kothari, Jayant and Darshana Dholakia (ed.). Narsinh Padmala. Ahmedabad: Gurjar Granthratna Karyalaya, 1997

- Rawal, Anantrai (ed.). Narsinh Mehta na Pado. Ahmedabad: Adarsh Prakashan

- Chandrakant Mehta, ed. (2016). Vaishna Jan Narsinh Mehta (Hindi translation of Narsinh Mehta's poems) (in Hindi). Gandhinagara: Gujarat Sahitya Akademi.

Critical material in English

- Neelima Shukla-Bhatt (2015). Narasinha Mehta of Gujarat: A Legacy of Bhakti in Songs and Stories. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-997641-6.

- Munshi, K.M. Gujarata and Its Literature: A Survey from the Earliest Times. Bombay: Longman Green and Co. Ltd. 1935

- Swami Mahadevananda (trans.) Devotional Songs of Narsi Mehta. Varanasi: Motilal Banarasidas, 1985.

- Tripathi, Govardhanram. Poets of Gujarat and their Influence on Society and Morals. Mumbai: Forbes Gujarati Sabha, 1958.

- Tripathi, Y.J. Kevaladvaita in Gujarati Poetry like akhil bhramand. Vadodara: Oriental Institute, 1958.

- Zhaveri, K.M. Milestones in Gujarati Literature. Bombay: N.M Tripathi and Co., 1938

- Zhaveri, Mansukhlal. History of Gujarati Literature. New Delhi: Sahitya Akademi, 1978.

Critical material in Gujarati

- Chaudhri, Raghuvir (ed.). Narsinh Mehta: Aswad Ane Swadhyay. Mumbai, M.P. Shah Women's College, 1983

- Dave, Ishwarlal (ed.). Adi Kavi Ni Aarsh Wani: Narsinh Mehta ni Tatvadarshi Kavita. Rajkot: Dr. Ishwarlal Dave, 1973

- Dave, Makarand. Narsinhnan Padoman Sidha-ras. A Lecture in Gujarati on Siddha-ras in poems of Narsinh Mehta. Junagadh: Adyakavi Narsinh Mehta Sahityanidhi, 2000

- Dave, R and A. Dave (eds.) Narsinh Mehta Adhyayn Granth. Junagadh: Bahuddin College Grahak Sahkari Bhandar Ltd., and Bahauddin College Sahitya Sabha, 1983

- Joshi, Umashankar, Narsinh Mehta, Bhakti Aandolanna Pratinidhi Udgaata' in Umashankar Joshi et al. (eds.). Gujarati Sahitya No Ithihas. vol. II. Ahmedabad: Gujarati Sahitya Parishad, 1975

- Munshi, K.M. Narsaiyyo Bhakta Harino. Ahmedabad: Gurjar Granthratna Karyalaya, 1952

- Shastri, K.K., Narsinh Mehta, Ek Adhyayan. Ahmedabad: B.J. Vidyabhavan, 1971

- Shastri, K.K., Narsinh Mehta. Rastriya Jeevan Charitramala. New Delhi: National Book Trust, 1972

References

- ^ a b c d e Ramanuj, Jagruti; Ramanuj, Vi (2012). Atmagnyani Bhaktakavi Narsinh Mehta (Biography of Narsinh Mehta). Ahmedabad: Navsarjan Publication. ISBN 978-93-81443-58-3.

- ^ Prasoon, Shrikant (2009). Indian Saints & Sages. Pustak Mahal. p. 169. ISBN 9788122310627.

- ^ a b Shukla-Bhatt, Neelima (2014). Narasinha Mehta of Gujarat : A Legacy of Bhakti in Songs and Stories. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 105–109, 213, 220. ISBN 9780199976416. OCLC 872139390 – via Oxford Scholarship.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Dholakiya, Darshana (1994). Narsinh Mehta (in Gujarati). Vallabh Vidyanagar: Sardar Patel University. pp. 8–20. OCLC 32204298.

- ^ "Gujarati cinema: A battle for relevance". 16 December 2012.

External links

| External videos | |

|---|---|