Prague uprising

| Prague uprising | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Czech resistance to Nazi occupation during World War II | |||||||

Residents greet Marshal Ivan Konev upon the arrival of the Red Army on 9 May 1945. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Russian Liberation Army (ROA) |

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Sergei Bunyachenko |

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

ROA 18,000[6] |

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

300 ROA insurgents killed and wounded[17][18][d] |

| ||||||

| 263[17]–2,000 Czech[20] and 1,000+ German[21][f] civilians killed | |||||||

The Prague uprising (Czech: Pražské povstání) of 1945 was a partially successful attempt by the Czech resistance to liberate the city of Prague from German occupation during World War II. The preceding six years of occupation had fuelled anti-German sentiment and the approach of the Soviet Red Army and the US Third Army offered a chance of success.

On 5 May 1945, in the last moments of the war in Europe, Czech citizens spontaneously attacked the German occupiers and Czech resistance leaders emerged from hiding to join the uprising. The Russian Liberation Army, which had been fighting for the Germans, defected and supported the Czechs. German troops counter-attacked, but their progress was slowed by barricades constructed by the Czech citizenry. On 8 May, the Czech and German leaders signed a ceasefire allowing the German forces to withdraw from the city, but not all Waffen-SS units obeyed. Fighting continued until 9 May, when the Red Army entered the nearly liberated city.

The uprising was brutal, with both sides committing war crimes. Violence against Germans, sanctioned by the Czechoslovak government, continued after the liberation, and was justified as revenge for the occupation or as a means to encourage Germans to flee. George Patton’s US Third Army was ordered by General Dwight Eisenhower not to come to the aid of the Czech insurgents, which undermined the credibility of the Western powers in postwar Czechoslovakia. Instead, the uprising was presented as a symbol of Czech resistance to Nazi rule, and the liberation by the Red Army was used by the Czechoslovak Communist Party to increase popular support for communism.

Background

German occupation

In 1938, the German Chancellor, Adolf Hitler, announced his intention to annex the Sudetenland, a region of Czechoslovakia with a high ethnic German population. As the previous appeasement of Hitler had shown, the governments of both France and Britain were intent on avoiding war.[23] British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain and French Prime Minister Édouard Daladier negotiated with Hitler and ultimately acquiesced to his demands at the Munich Agreement, in exchange for guarantees from Nazi Germany that no additional lands would be annexed. No Czechoslovak representatives were present at the negotiations.[24] Five months later, when the Slovak Diet declared the independence of Slovakia, Hitler summoned Czechoslovak President Emil Hácha to Berlin and forced him to accept the German occupation of the Czech rump state and its re-organisation into the German-dominated Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia.[25] Germany promptly invaded and occupied the remaining Czech territories. Although France had a defensive alliance with Czechoslovakia, neither the French nor British intervened militarily.[26]

The Nazis considered many Czechs to be ethnically Aryan, and therefore suitable for Germanisation.[27] As a consequence, the German occupation was less harsh than in other Slavic nations. Wartime living standards were actually higher in the occupied region than in Germany itself.[28] However, freedom of speech was curtailed and 400,000 Czechs were conscripted for forced labour in the Reich.[29] During the six-year occupation, more than 20,000 Czechs were executed and thousands more died in concentration camps.[30] In 1941, the Nazi Reinhard Heydrich was made Deputy Protector of Bohemia and Moravia and began enforcing the occupation more harshly.[29] Within five days of Heydrich's arrival, 142 people were executed.[31] His brutality led to the Allies ordering his assassination the following year,[32] but the Germans killed more than a thousand Czechs in reprisal, including the entire villages of Lidice and Ležáky.[33] While the general violence of the occupation was much less severe than in Eastern Europe,[28][34] it nevertheless incited violent anti-German sentiment in many Czechs.[35]

Military situation

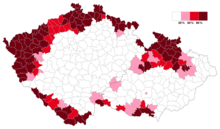

Front

Front

Front

Red: Soviet / Grey: German / Green: U.S.

During the spring of 1945, partisan forces in Bohemia and Moravia totalled about 120 groups, with a combined strength of around 7,500 people.[37] Partisans disrupted the railway and highway transportation by sabotaging track and bridges and attacking trains and stations. Some railways could not be used at night or on some days, and trains were forced to travel at a slower speed.[38] Waffen-SS units retreating from the Red Army's advance into Moravia burned down entire villages as a reprisal.[16] Despite losing much of their leadership to a March 1945 purge by the Gestapo, Communist groups in Prague distributed propaganda leaflets calling for an insurrection.[39] German soldiers and civilians became increasingly worried and prepared to flee violent retaliation for the occupation.[40] In an attempt to reassert German authority, SS police general Karl Hermann Frank broadcast a message over the radio threatening to destroy Prague and drown any opposition in blood.[41]

In early 1945, former Czechoslovak Army officers set up the Bartoš Command commanded by General Karel Kutlvašr to oversee fighting inside Prague, and the Alex Command under General František Slunečko to direct insurgent units in the suburbs.[42] Meanwhile, the Czech National Council (cs), with representatives from various Czech political parties, formed to take over political leadership after the overthrow of the Nazi and collaborationist authorities.[43] Military leaders planning an uprising within Prague counted on the loyalty of ethnically Czech members of the police and the Government Army of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, as well as employees of key civil services, such as transport workers and the fire brigade.[44] The Russian Liberation Army (ROA), composed of Soviet POWs that had agreed to fight for Nazi Germany, was stationed outside of Prague. Hoping that the ROA could be persuaded to switch sides in order to avoid accusations of collaboration, the Czech military command sent an envoy to General Sergei Bunyachenko, commander of the 1st ROA Infantry Division (600th German Infantry Division). Bunyachenko agreed to help the Czechs.[6][45]

On 4 May, the US Third Army under General George S. Patton entered Czechoslovakia.[46] British Prime Minister Winston Churchill was the only political leader to advocate the liberation of Prague by the Western Allies. In a telegram to General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Supreme Allied Commander in Europe, Churchill said that "the liberation of Prague...by US troops might make the whole difference to the postwar situation of Czechoslovakia and might well influence that in nearby countries."[47] Joseph Stalin, leader of the Soviet Union, also wanted his forces to liberate the city, and asked that the Americans stop at Plzeň, 50 miles to the west.[48] The Red Army was planning a major offensive into the Protectorate, due to start 7 May.[49] Eisenhower, disinclined to accept American casualties or risk antagonising the Soviet Union, acquiesced to the Soviet demands that the Red Army enter Prague.[50]

Uprising

5 May

Staff of Czech Radio opposed to the occupation began the morning by broadcasting in the banned Czech language.[51] The Bartoš Command and Communist groups met separately and both scheduled the armed uprising to begin 7 May.[52] Czech citizens gathered in the streets, vandalised German inscriptions, and tore down German flags.[45] Czechoslovak flags appeared openly in windows and on jacket lapels.[53][54] Tram operators refused to accept Reichmarks or to give the stops in German, as was required by the occupiers. Some German soldiers were surrounded and killed.[20] In response to growing popular agitation, Frank threatened to shoot Czechs gathering in the streets,[55] and increased armed German patrols.[56] Some German soldiers began to fire into the crowds.[57]

Around noon, the radio broadcast a series of appeals to the police and gendarmerie requesting aid in fighting SS guards inside the radio building.[58] A detachment of Government Army policemen responded to the call, and met stiff resistance as they retook the building.[59][60] During the entire time, the radio continued to broadcast.[61] Although not directed at the populace, the appeal ignited fighting all over the city, concentrated in the downtown districts.[62] Crowds of unarmed civilians, mostly young men with no military training, overwhelmed German garrisons and stores.[4] Many casualties were inflicted by German soldiers and civilians sniping from strong-points or rooftops; in response, Czech forces began to intern Germans and suspected collaborators.[56] Czech noncombatants assisted by setting up makeshift hospitals for the wounded and bringing food, water, and other necessities to the barricades, while German forces were often resorted to looting to obtain essential supplies.[63] Czech forces seized thousands of firearms, hundreds of Panzerfausts, and five armoured vehicles, but still suffered a shortage of weapons.[64]

By the end of the day, the resistance had seized most of the city east of the Vltava River. The insurgents held many important buildings, including the radio, the telephone exchange, most railway stations, and ten of twelve bridges. Three thousand prisoners were liberated from Pankrác Prison.[65] By controlling the telephone exchange, resistance fighters were able to sever communication between German units and commanders. German forces held most of the territory to the west of the river, including an airfield at Ruzyně, northwest of the city, and various surrounded garrisons such as the Gestapo Headquarters.[65]

At the orders of Field Marshal Ferdinand Schörner, in command of Axis forces in Bohemia, Waffen-SS units were pulled from fighting the Red Army and sent into Prague. The SS was relatively well-equipped with tanks, armoured carriers, weaponry and motorised units. Information on this force movement reached insurgent headquarters late in the day.[66] The radio broadcast appeals in English and Russian for an air attack on the tanks.[67]

Hearing of events in Prague, Patton asked for permission to advance to the Vltava in order to aid the Czech resistance, but Eisenhower refused.[50][g] The Red Army was ordered to advance the launch of its offensive to 6 May.[69][70]

6 May

Late in the evening on 5 May, the radio broadcast an appeal to the people in the streets of Prague to build barricades in order to slow the anticipated German attack. Despite poor weather, tens of thousands of civilians worked overnight to construct over 1,600 barricades by morning.[71] A total of 2,049 were constructed by the end of the uprising.[72]

SS General Carl Friedrich von Pückler-Burghauss ordered the Luftwaffe to firebomb Prague, but the attack had to be scaled back due to lack of fuel.[70] The first strike was made by two Messerschmitt Me 262A jet fighter-bombers from elements of KG 51 at Ruzyně.[73] One of their targets was the radio building, which was hit by a 250-kg bomb that disabled the transmitter. However, the radio continued to broadcast from alternate locations.[73] In successive attacks, the Luftwaffe bombed barricades and hit apartment buildings with incendiary bombs, causing many civilian casualties.[74][75]

At midday, the First Battalion of the ROA entered Prague and attacked the Germans;[54][76] during its time in Prague, it disarmed around 10,000 German soldiers.[6] An American reconnaissance patrol met with an ROA officer as well as Czech leaders. This was when the Czechs learnt of the demarcation line agreement and that the Third Army was not coming to liberate Prague. As a consequence, the Czech National Council, which had not been involved in negotiations with Bunyachenko, denounced the ROA.[77] A Soviet liberation meant that they could not politically afford to endorse the ROA, whom Stalin considered traitors.[6][54] Despite the rejection of the ROA, their aid to Prague became a point of friction between Moscow and Czechoslovakia after the war.[78]

7 May

Under the terms of the provisional unconditional surrender, signed in the early hours of 7 May, German forces had a forty-eight-hour grace period to cease offensive operations.[79] Eisenhower hoped that the capitulation would put an end to the fighting in Prague and therefore obviate American intervention.[80] However, the German leadership was determined to use the grace period to move as many soldiers as possible westward to surrender to the Americans.[81] Schörner denounced the rumours of a ceasefire in Prague and said that the truce did not apply to German forces fighting the Red Army or Czech insurgents.[80]

In order to gain control of Prague's transportation network, the Germans launched their strongest attack of the uprising.[81] Waffen-SS armoured and artillery units arriving in Prague gradually punched through the barricades with several tank attacks.[82] Intense fighting was accompanied with the SS use of Czech civilians as human shields[5] and damage to the Old Town Hall and other historic buildings.[83] When the Bartoš Command learnt of the Rheims surrender, it ordered an immediate ceasefire for Czech forces. This caused some confusion among the defenders, who were also suffering from desertion due to the worsening military situation.[84] The ROA played a decisive role in slowing the progress of the Germans,[81] but withdrew from Prague over the afternoon and evening in order to surrender to the US Army. Only a few ROA units stayed in the city, departing late on 8 May.[5] With the bulk of the ROA gone, the poorly armed and untrained Czech insurgents fared badly against the reinforced German forces.[83] By the end of the day, German forces had taken much of the rebel-held territory east of the Vltava, with the resistance only holding a salient in the Vinohrady-Strašnice area.[85] ROA forces captured the Luftwaffe airfield at Ruzyně, destroying several aircraft.[10]

8 May

In the morning, the Germans made an air and artillery bombardment followed by a renewed infantry attack.[86] The fighting was almost as intense as the previous day. One particularly fierce battle took place at the Masaryk train station. At 10 am, SS troops captured the station and murdered around 50 surrendered resistance fighters and noncombatants (cs).[5][h] In one of the last battles of the uprising, Czech insurgents regained the train station at 2 am on 9 May[5] and photographed the victims' bodies.[89]

Faced with military collapse, no arriving Allied help, and threats to destroy the city, the Czech National Council agreed to negotiate with Wehrmacht General Rudolf Toussaint.[90] Toussaint, running out of time to evacuate Wehrmacht units westward, was in an equally desperate position.[81] After several hours of negotiations, it was agreed that on the morning of 9 May, the Czechs would allow German soldiers to pass westward through Prague, and in exchange German forces leaving the city would surrender their arms.[91] A ceasefire was finally agreed to around midnight. However, some pockets of German forces were unaware of or disobeyed the ceasefire,[78] and civilians feared a continuation of the German atrocities which had intensified over the previous two days. Late in the evening, reports reached Prague of the liberation of Theresienstadt concentration camp, northwest of the city, and the advance of the Red Army into other areas north of Prague.[92]

9 May

The last of the German forces to escape Prague left in the early hours of the morning.[93] At 4:00, elements of the 1st Ukrainian Front reached the suburbs of Prague. Fighting was mostly with isolated SS units that had been prevented from withdrawing by Czech insurgents. Over the next few hours, the Red Army quickly overcame the remaining German forces.[94] Because most of the Germans had already left, the 1st Ukrainian Front avoided the house-to-house fighting that had occurred in the capture of Budapest and Vienna.[95] The Red Army lost only ten soldiers in what has been described as their "easiest victory" of the war.[96][i] At 8:00 am, the tanks reached the centre city and the radio announced the arrival of the Soviet forces. Czechs poured out into the streets to welcome the Red Army.[98]

War crimes

German

German forces committed war crimes against Czech civilians throughout the uprising. Many people were killed in summary executions, and the SS used Czech civilians as human shields,[1][5] forced them to clear barricades at gunpoint, and threatened to shoot hostages in revenge for German soldiers killed in action.[89] When tanks were halted by barricades, they were known to fire into surrounding houses.[89] After violently evicting or murdering the inhabitants, German soldiers looted and burned Czech houses and apartment buildings.[89] On several occasions, more than twenty people were killed at once; most of the massacres occurred on 7 and 8 May.[89] Among those killed were pregnant women and young children, and some of the dead were found mutilated.[74][100] After the uprising, a Czech police report described war crimes committed by the SS:

The doors of houses and flats were burst in, houses and shops were plundered, dwellings were demolished... The inhabitants were driven from their homes and forced to form a living wall with their bodies to protect German patrols, and constantly threatened with automatic pistols... Many Czechs lay dead in the streets.[74][101]

Most of the German war crimes were committed by the Waffen-SS. However, Luftwaffe soldiers, along with the SA, participated in the torture and murder of prisoners held at the Na Pražačce school.[89]

Czech

The Czechoslovak government-in-exile planned to expel the German minority of Czechoslovakia in order to create an ethnically pure Czech-Slovak nation-state.[16][35] Throughout the occupation, Czech politicians had broadcast messages from London calling for violence against German civilians and suspected Czech collaborators.[35] President Edvard Beneš believed that vigilante justice would be less divisive than trials, and that encouraging Germans to flee would spare the effort of deporting them later.[102] Before he arrived in Czechoslovakia, he broadcast that "everyone who deserves death should be totally liquidated... in the popular storm"[103] and urged the resistance to avenge Nazi crimes "a thousand times over."[104] Minister of Justice Prokop Drtina asked resistance leaders to make liberation "bloody" for the Germans and to drive them out with violence.[104] Communist leaders also supported the violence.[35] Military leaders not only overlooked anti-German massacres and failed to punish the perpetrators, but actively encouraged them.[105] The Czech Radio likely played a role in inciting the violence by passing on the anti-German messages of these political leaders,[20][35] as well as broadcasting anti-German messages on its own initiative.[105] Almost no one was prosecuted for violence against Germans, and a bill was proposed in the postwar parliament that would have retroactively legalised it.[106]

In Prague, Czech insurgents murdered surrendered German soldiers and German civilians both before and after the arrival of the Red Army.[107] Historian Robert Pynsent argues that there was no clear-cut distinction between the end of the uprising and the beginning of the expulsions.[108] Some captured German soldiers were hung from lampposts and burned to death,[75][109] or otherwise tortured and mutilated.[110] Czech rioters also assaulted, raped, and robbed German civilians.[20] Not all those killed or affected by anti-German violence were actually German or collaborators, as perpetrators frequently acted on suspicion,[107][111] or exploited the chaos to settle personal grudges.[112] In one massacre at Bořislavka on 10 May, forty German civilians were murdered.[113] During and after the uprising, thousands of German civilians and surrendered soldiers were interned in makeshift camps where food and hygiene were poor. Survivors claimed that beatings and rape were commonplace.[114][115] The violence against German civilians continued throughout the summer, culminating in the expulsion of Sudeten Germans. About three million Czechoslovak citizens of German ethnicity were stripped of their citizenship and property and forcibly deported.[116]

Legacy

As "the greatest military action of the Czechs for freedom and national independence fought on their own territory,"[j] in the words of journalist Jindřich Marek,[118] the Prague uprising became a national myth of the new Czechoslovak republic and the subject of much literature.[117]

The Western Allies' failure to liberate Prague was seen as emblematic of their lack of concern for Czechoslovakia, first demonstrated by the Munich Agreement. It also served as a blow to democratic forces within the country who opposed Czechoslovakia's drift towards communism in the years after the war.[50] It was not forgotten that Stalin had opposed the Munich Agreement, and Prague's liberation by the Red Army turned public opinion in favour of communism.[119][k] Few Czechs were aware of the demarcation line agreement between the Western Allied and Soviet forces,[120] allowing communists to accuse the American forces of "having remained a cowardly or cynical onlooker while Prague was struggling for life," in the words of Hungarian historian Stephen Kertesz.[121] According to British diplomat Sir Orme Sargent, the Prague uprising was the moment that "Czechoslovakia was now definitely lost to the West."[50]

In 1948, the democratic government of Czechoslovakia was toppled by a Communist coup d'état.[122] Following the coup, Czechoslovakia became a communist state aligned with the Soviet Union until the Velvet Revolution in 1989.[123] The Communist government attempted to discredit the Czech resistance, which was considered a threat to Communist legitimacy, by purging or arresting former resistance leaders,[124] and distorting history, for instance overstating the role of the working class in the uprising[l] and inflating the number of Red Army soldiers killed in Prague.[125][m]

References

Notes

- ^ The Prague police and gendarmerie as well as the First Battalion of the Government Army were lightly armed and had a strength of a few thousand.[2] The remainder were civilians, mostly young men without military training.[3] Some fighters were women,[4] and others escaped prisoners of war of various nationalities, including Soviet, French, Dutch, and British.[5] Some Jews who had escaped or been liberated from concentration camps also fought, something that is often overlooked in literature about the uprising.[5]

- ^ About 10,000 were highly-trained, experienced Waffen-SS soldiers, who were sent to Prague after the start of the uprising.[7] The remainder included regular Wehrmacht infantry, former members of the disbanded Luftwaffe I. Flakkorps,[8] Hitler Youth, and German civilians who had taken up arms.[9]

- ^ The lower figure is the official estimate published in 1946.[13] Only casualties whose identity could be verified were included.[14] The higher figure is quoted from Marek 2015.[12]

- ^ Bunyachenko said that ROA casualties in the Prague uprising were 300 killed or wounded, but MacDonald suggests that this may have been "exaggerated for political purposes" as Bunyachenko was trying to avoid being handed over into Soviet captivity.[18]

- ^ Theoretically, these figures include civilian casualties. However, Staněk considers the total number of Germans killed by violent means to be considerably higher than 1,000.[19]

- ^ The official figure of 1,000 German civilian casualties is "almost certainly an underestimate, especially considering the scope and nature of the violence that took place in and around the city, and doesn't take into account official attempts to play down the violence against civilians." For example, of 300 Germans buried in a mass grave in a suburb of Prague, three-quarters were classified as military casualties despite the fact that a majority were wearing civilian clothes.[22]

- ^ About this decision, Patton later wrote: "I felt, and I still feel, that we should have gone on to the [Vltava] River and, if the Russians didn't like it, let them go to hell. I did not find out until weeks afterwards the reasons, which were sound, which implemented General Eisenhower's decision..."[68]

- ^ According to the police report, there were 53 victims;[87] Bartošek says that 47 were killed;[88] Pynsent's figure is 58.[5]

- ^ The offensive that had put the 1st Ukrainian Front in position to liberate Prague was less bloodless, with Soviet forces suffering nearly 50,000 casualties.[97]

- ^ Pynsent points out that this is a true but weak statement, because the Czech lands had not been the site of major armed insurrection either before 1945 or afterwards.[117]

- ^ This took place in spite of multiple instances during the Red Army's advance into the country where Soviet soldiers committed rape and stole from the Czech civilian population.[96]

- ^ In fact, the majority of those killed were from the petite bourgeoisie and less than a fifth were working-class.[14]

- ^ Communist sources give between 400 and 500 Red Army soldiers killed, which is more than an order of magnitude over that estimated by the best sources.[126] Such inflation is often accompanied by rhetoric similar to Bartošek's statement that, on 9 May, "the alliance of the fraternal peoples of the Soviet Union and Czechoslovakia [was] sealed in blood."[127][126]

Citations

- ^ a b c Mahoney 2011, p. 191.

- ^ Bartošek 1965, pp. 34–35.

- ^ Bartošek 1965, pp. 55, 149–150.

- ^ a b Bartošek 1965, p. 53.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Pynsent 2013, p. 297.

- ^ a b c d Julicher 2015, p. 171.

- ^ Dickerson 2018, p. 97.

- ^ Jakl 2004, p. 25.

- ^ Bartošek 1965, p. 54.

- ^ a b Thomas & Ketley 2015, p. 284.

- ^ Kokoška 2005, p. 258.

- ^ a b "Publikace, kterou historiografie potřebovala: padlí z pražských barikád 1945". Vojenském historickém ústavu Praha. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

- ^ Soukup 1946, p. 42.

- ^ a b Pynsent 2013, p. 285.

- ^ Soukup 1946, p. 39.

- ^ a b c Orzoff 2009, p. 207.

- ^ a b Marek 2005, pp. 13–14.

- ^ a b MacDonald & Kaplan 1995, p. 186.

- ^ a b Staněk 2005, p. 197.

- ^ a b c d Merten 2017, p. 114.

- ^ Lowe 2012, p. 127.

- ^ Lowe 2012, pp. 127–128.

- ^ Noakes & Pridham 2010, p. 102.

- ^ Bryant 2007, p. 24.

- ^ Noakes & Pridham 2010, p. 119.

- ^ Bryant 2007, p. 28.

- ^ Bryant 2007, p. 126.

- ^ a b Duffy 2014, p. 282.

- ^ a b Kuklík 2015, p. 118.

- ^ Ėrlikhman 2004, p. 54.

- ^ Šír, Vojtěch (3 April 2011). "První stanné právo v protektorátu" [The First Martial Law in Protectorate]. Fronta.cz (in Czech). Retrieved 24 June 2018.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Burian 2002, p. 31.

- ^ Burian 2002, p. 90.

- ^ Bryant 2007, p. 62.

- ^ a b c d e Frommer 2005, p. 42.

- ^ Location data from the Soviet history of World War II (История второй мировой войны 1939–1945 в двенадцати томах) Map 151 and 12th Army Group Situation Map

- ^ Bartošek 1965, p. 101.

- ^ Bartošek 1965, pp. 101–102.

- ^ Bartošek 1965, pp. 42, 75, 113.

- ^ Bartošek 1965, pp. 76–77.

- ^ "Projev K. H. Franka k českému národu (30. 4. 1945)" (in Czech). Retrieved 3 July 2018.

- ^ Bartošek 1965, pp. 34–36.

- ^ Bartošek 1965, pp. 34, 40–41.

- ^ Bartošek 1965, p. 35.

- ^ a b MacDonald & Kaplan 1995, p. 175.

- ^ Fuller 2003, pp. 108, 149.

- ^ Olson 2018, p. 427.

- ^ Erickson 1983, pp. 625–630.

- ^ Erickson 1983, p. 627.

- ^ a b c d Olson 2018, p. 429.

- ^ Bartošek 1965, pp. 18, 22–23.

- ^ Pynsent 2013, pp. 290, 296.

- ^ Bartošek 1965, p. 19.

- ^ a b c Dickerson 2018, p. 96.

- ^ Bartošek 1965, p. 18.

- ^ a b Bartošek 1965, p. 29.

- ^ Bartošek 1965, pp. 18–19.

- ^ Bartošek 1965, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Bartošek 1965, p. 25.

- ^ Pynsent 2013, p. 296.

- ^ Vaughan, David. "The Battle of the Airwaves: the extraordinary story of Czechoslovak Radio and the 1945 Prague Uprising". Radio Prague. Retrieved 6 July 2018.

- ^ Bartošek 1965, pp. 24, 31.

- ^ Bartošek 1965, p. 151.

- ^ Bartošek 1965, pp. 53, 128.

- ^ a b Bartošek 1965, pp. 50–54.

- ^ Bartošek 1965, pp. 51–53, 79, 127–128.

- ^ Erickson 1983, p. 634.

- ^ Patton & Harkins 1995, p. 327.

- ^ Glantz & House 1995, p. 273.

- ^ a b Kershaw 2012, p. 370.

- ^ Bartošek 1965, pp. 129, 135, 136.

- ^ "Build Barricades / Exhibition to commemorate the 70th anniversary of the Prague Uprising". The City of Prague Museum. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

- ^ a b "Německé" (in Czech). Czech Radio. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

- ^ a b c Tampke 2002, p. 87.

- ^ a b MacDonald & Kaplan 1995, p. 190.

- ^ Bartošek 1965, pp. 155–157.

- ^ Andreyev 1989, p. 75.

- ^ a b Pynsent 2013, p. 284.

- ^ Act of Military Surrender Signed at Rheims at 0241 on the 7th day of May 1945, The Avalon Project, Yale Law School, © 1996–2007, The Lillian Goldman Law Library in Memory of Sol Goldman.

- ^ a b MacDonald & Kaplan 1995, p. 185.

- ^ a b c d Jakl 2013, p. 3.

- ^ Bartošek 1965, p. 148.

- ^ a b MacDonald & Kaplan 1995, p. 192.

- ^ Bartošek 1965, pp. 196, 209–210.

- ^ Bartošek 1965, p. 147.

- ^ Bartošek 1965, p. 212.

- ^ "Masakr na Masarykově nádraží 8. 5. 1945" (in Czech). Retrieved 16 June 2018.

- ^ Bartošek 1965, p. 211.

- ^ a b c d e f "Masakry českých civilistů a zajatců během Pražského povstání" (in Czech). Retrieved 7 July 2018.

- ^ Bartošek 1965, pp. 215–217.

- ^ Bartošek 1965, p. 222.

- ^ Bartošek 1965, p. 224.

- ^ Jakl 2013, p. 4.

- ^ Bartošek 1965, p. 226.

- ^ Pynsent 2013, p. 288.

- ^ a b Lukes 2012, p. 50.

- ^ Glantz & House 1995, p. 300.

- ^ Bartošek 1965, p. 232.

- ^ "Vraždy ve škole Na Pražačce 5. 5. 1945" (in Czech). Retrieved 17 June 2018.

- ^ Pynsent 2013, p. 298.

- ^ Merten 2017, pp. 114–115.

- ^ Frommer 2005, pp. 40–41.

- ^ Frommer 2005, p. 41.

- ^ a b Frommer 2005, p. 40.

- ^ a b Pynsent 2013, p. 281.

- ^ Pynsent 2013, p. 321.

- ^ a b Pynsent 2013, p. 309.

- ^ Pynsent 2013, p. 320.

- ^ Duffy 2014, p. 283.

- ^ Pynsent 2013, p. 299.

- ^ Frommer 2005, p. 43.

- ^ Pynsent 2013, p. 280.

- ^ Puhl, Jan (2 June 2010). "Massacre in Czechoslovakia: Newly Discovered Film Shows Post-War Executions". Spiegel Online. Retrieved 24 June 2018.

- ^ Lowe 2012, pp. 128–129.

- ^ Ther & Siljak 2001, p. 206.

- ^ Ther & Siljak 2001, p. 62.

- ^ a b Pynsent 2013, p. 282.

- ^ Marek 2005, p. 12.

- ^ MacDonald & Kaplan 1995, p. 198.

- ^ Pynsent 2013, p. 286.

- ^ Kertesz 1956, p. 203.

- ^ Lukes 2012, p. 4.

- ^ Swain & Swain 2017, pp. 153, 330.

- ^ Pynsent 2013, pp. 293–294.

- ^ Pynsent 2013, pp. 282–283, 285.

- ^ a b Pynsent 2013, pp. 284–285.

- ^ Bartošek 1965, p. 227.

Bibliography

- Andreyev, Catherine (1989). Vlasov and the Russian Liberation Movement: Soviet Reality and Emigré Theories. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521389600.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bartošek, Karel (1965). The Prague Uprising. Artia.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bryant, Chad Carl (2007). Prague in Black: Nazi Rule and Czech Nationalism. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674024519.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Burian, Michal (2002). "Assassination — Operation Arthropoid, 1941–1942" (PDF). Ministry of Defence of the Czech Republic. Retrieved 20 May 2010.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Dickerson, Bryan J. (2018). The Liberators of Pilsen: The U.S. 16th Armored Division in World War II Czechoslovakia. McFarland. ISBN 9781476671147.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Duffy, Christopher (2014). Red Storm on the Reich: The Soviet March on Germany 1945. Routledge. ISBN 9781136360336.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Erickson, John (1983). The Road to Berlin. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0297772385.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ėrlikhman, Vadim (2004). Poteri narodonaselenii︠a︡ v XX veke: spravochnik. Moskva: Russkai︠a︡ panorama. ISBN 978-5-93165-107-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Frommer, Benjamin (2005). National Cleansing: Retribution Against Nazi Collaborators in Postwar Czechoslovakia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521008969.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Fuller, Robert Paul (2003). Last Shots for Patton's Third Army. New England Transportation Research. ISBN 9780974051901.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Glantz, David M.; House, Jonathan M. (1995). When Titans Clashed: How the Red Army Stopped Hitler. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-0899-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Jakl, Tomáš (2013). "České národní povstání v květnu 1945" (in Czech). Vojenský historický ústav Praha.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Jakl, Tomáš (2004). Květen 1945 v českých zemích (in English and Czech). Miroslav Bílý. ISBN 9788086524078.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Julicher, Peter (2015). "Enemies of the People" Under the Soviets: A History of Repression and Its Consequences. McFarland. ISBN 9780786496716.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kershaw, Ian (2012). The End: The Defiance and Destruction of Hitler's Germany, 1944–1945. Penguin. ISBN 9780143122135.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kertesz, Stephen Denis (1956). The fate of East Central Europe: hopes and failures of American foreign policy. University of Notre Dame Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kokoška, Stanislav (2005). Praha v květnu 1945: historie jednoho povstání (in Czech). Lidové noviny. ISBN 9788071067405.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kuklík, Jan (2015). Czech law in historical contexts. Charles University in Prague, Karolinum Press. ISBN 9788024628608.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lowe, Keith (2012). Savage Continent: Europe in the Aftermath of World War II. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 9781250015044.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lukes, Igor (2012). On the Edge of the Cold War: American Diplomats and Spies in Postwar Prague. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195166798.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - MacDonald, Callum; Kaplan, Jan (1995). Prague in the shadow of the swastika: a history of the German occupation 1939 - 1945. Melantrich. ISBN 9788070232118.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Mahoney, William (2011). The History of the Czech Republic and Slovakia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9780313363061.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Marek, Jindřich [in Czech] (2005). Barikáda z kaštanů: pražské povstání v květnu 1945 a jeho skuteční hrdinové (in Czech). Svět křídel. ISBN 9788086808161.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Marek, Jindřich (2015). Padli na barikádách: padlí a zemřelí ve dnech Pražského povstání 5.-9. května 1945 (in Czech). Vojenský Historický Ústav. ISBN 9788072786527.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Mastný, Vojtěch (1971). The Czechs Under Nazi Rule: The Failure of National Resistance, 1939–1942. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-03303-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Merten, Ulrich (2017). Forgotten Voices: The Expulsion of the Germans from Eastern Europe After World War II. Routledge. ISBN 9781351519540.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Noakes, J.; Pridham, G. (2010) [2001]. Nazism 1919–1945: Foreign Policy War, and Racial Extermination. Vol. 3 (2nd ed.). Devon: University of Exeter Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Okęcki, Stanisław (1987). Polacy W Ruchu Oporu Narodów Europy. PWN--Polish Scientific Publishers. ISBN 9788301068608.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Olson, Lynne (2018). Last Hope Island: Britain, Occupied Europe, and the Brotherhood That Helped Turn the Tide of War. Random House Publishing Group. ISBN 9780812987164.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Orzoff, Andrea (2009). Battle for the Castle: The Myth of Czechoslovakia in Europe, 1914–1948. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199709953.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Patton, George Smith; Harkins, Paul Donal (1995). War as I Knew it. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-0395735299.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Pynsent, Robert B. [in Czech] (18 July 2013). "Conclusory Essay: Activists, Jews, The Little Czech Man, and Germans" (PDF). Central Europe. 5 (2): 211–333. doi:10.1179/174582107x190906.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Roučka, Zdeněk. Skončeno a podepsáno: Drama Pražského povstání (Accomplished And Signed: Pictures of the Prague Uprising), 163 pages, Plzeň: ZR&T, 2003 (ISBN 80-238-9597-4).

- Staněk, Tomáš (2005). Poválečné "excesy" v českých zemích v roce 1945 a jejich vyšetřování (in Czech). Ústav pro soudobé dějiny.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Soukup, Jan (1946). Prhehled bojur Pražského povstání ve dnech 5.–9. kvehtna 1945, inPražská květnová revoluce 1945: k prvnímu výročí slavného povstání pražského lidu ve dnech 5.-9 (in Czech). Hlavní město Praha. pp. 16–45.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Swain, Geoffrey; Swain, Nigel (2017). Eastern Europe Since 1945. Macmillan International Higher Education. ISBN 9781137605139.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Tampke, Jürgen (2002). Czech-German Relations and the Politics of Central Europe: From Bohemia to the EU. Springer. ISBN 9780230505629.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Ther, Philipp; Siljak, Ana (2001). Redrawing Nations: Ethnic Cleansing in East-Central Europe, 1944–1948. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9780742510944.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Thomas, Geoffrey J.; Ketley, Barry (2015). Luftwaffe KG 200: The German Air Force's Most Secret Unit of World War II. Stackpole Books. ISBN 9780811716611.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

External links

- Czechs commemorate Prague revolt, BBC News, 5 May 2005

- Prague's war: Legacy of questions - Historians still debate myths and mysteries of the liberation, The Prague Post, 5 May 2005

- Summary of the Prague uprising

- (in Czech) Picture gallery of Prague uprising - a gallery located at the official website of The Prague City Archives

- (in Czech) Execution of German civilians in Prague (9 May 1945) (Czech TV documentary) (Adobe Flash Player, 2:32 min)

- (in Czech) War crimes committed by Germans in Prague, including graphic images