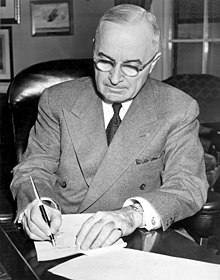

Foreign policy of the Harry S. Truman administration

The foreign policy of the Harry S. Truman administration was the foreign policy of the United States from April 12, 1945 to January 20, 1953, when Harry S. Truman served as the President of the United States. The Truman administration's foreign policy primarily addressed the end of World War II, the aftermath of that war, and the beginning of the Cold War. Truman's presidency was a turning point in foreign affairs, as the United States engaged in an internationalist foreign policy and renounced isolationism.

Truman took office upon the death of Franklin D. Roosevelt during the final year of World War II. Truman had not generally shown a strong interest in foreign affairs prior to taking office, and as president he relied heavily on advisers like George Marshall and Dean Acheson, both of whom served as Secretary of State under Truman. Nazi Germany surrendered shortly after Truman took office, but the Empire of Japan initially refused to surrender. In order to force Japan's surrender without resorting to an invasion of the main Japanese islands, Truman approved of the military's plans to drop atomic bombs on two Japanese cities. After Japan surrendered on September 1945, the Truman administration worked with the Soviet Union, Britain, and other Allied leaders to establish post-war international institutions and agreements such as the United Nations, the International Refugee Organization, and the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade. The Truman administration also embarked on a policy of rebuilding Japan and West Germany, and both countries would become aligned with the United States after the war.

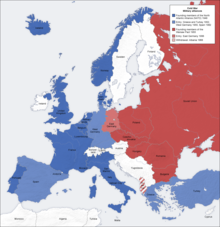

Tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union escalated after 1945, and by 1947 the two countries had entered a sustained period of geopolitical tension known as the Cold War. Truman adopted a policy of containment, in which the U.S. would attempt to prevent the spread of Communism but would not actively seek to regain territory already lost to Communism. He also announced the Truman Doctrine, a policy of aiding countries in danger of falling to Communism. Pursuant to this doctrine, Truman convinced Congress to provide an unprecedented aid package to Greece and Turkey, overcoming opposition from isolationists and some on the left who favored more conciliatory policies towards the Soviet Union. The following year, Truman convinced Congress to approve the Marshall Plan, $13 billion aid package enacted to rebuild Western Europe. In 1949, the U.S., Canada, and several European countries signed the North Atlantic Treaty, establishing the NATO military alliance. Meanwhile, domestic fears of Soviet espionage led to a Red Scare and the rise of McCarthyism in the United States.

The Truman administration attempted to mediate the Chinese Civil War, but the Communist faction under Mao Zedong took control of Mainland China in 1949. The following year, North Korea invaded South Korea in an attempt to reunify the country. Acting under the aegis of the United Nations, the U.S. intervened in the war and gained a military advantage over North Korea until Chinese forces crossed into Korea. After a long withdrawal, the U.S. launched a successful counter attack, and the war settled into a stalemate for the remainder of Truman's term. Truman left office quite unpopular, but scholars generally consider him to be an above average president, and his administration has been credited for establishing Cold War policies that ultimately proved successful.

Leadership

When he first took office, Truman asked all the members of Roosevelt's cabinet to remain in place for the time being, but by the end of 1946 only one Roosevelt appointee, Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal, remained.[1] Truman himself had little experience or interest in foreign affairs – he specialized in domestic politics and discovering waste and inefficiency in wartime spending. Even as vice president, knowing of the president's poor health, he showed little curiosity and was kept out of the loop.[2] Since Truman was not well informed on foreign affairs, and he had a weak White House staff, he relied heavily on top advisers, primarily from the State Department.[3] Truman quickly replaced Secretary of State Edward Stettinius Jr. with James F. Byrnes, a close personal friend of Truman's. By 1946, Truman was taking a hard line against this Kremlin, and Burns was still trying to be conciliatory. The divergence in policy was intolerable.[4] Truman replaced Byrnes with the highly prestigious five-star army general George Marshall in January 1947, Despite Marshall's failure in negotiating a settlement in the Chinese Civil War.[5][6] In 1947, Forrestal became the first Secretary of Defense, overseeing all branches of the United States Armed Forces.[7] Mental illness sent Forrestal into retirement in 1949, and he was replaced successively by Louis A. Johnson, Marshall, and finally Robert A. Lovett.[8]

At the Department of State, the key person was Dean Acheson, who replaced Marshall as secretary in 1949. The Marshall Plan embodied Acheson's analysis of the European crisis; he designed America's role. As tensions mounted with Moscow, Acheson moved from guarded optimism to pessimism. He decided negotiations were futile, and the United States had to mobilize a network of allies to resist the Kremlin's quest for world domination, using both military and especially economic power. Downplaying the importance of communism in China, Acheson emphasized Europe, and took the lead, as soon as he became Secretary of State in January 1949, to nail down the NATO alliance. It worked closely with the major European powers, as well as cooperating closely with Republican Senator Arthur Vandenberg, build bipartisan support at a time when the Republicans controlled Congress after the 1946 elections.[9] According to Townsend Hoopes, throughout his long career, Acheson displayed:

- exceptional intellectual power and purpose, and tough inner fiber. He projected the long lines and aristocratic bearing of the thoroughbred horse, a self-assured grace, an acerbic elegance of mind, and a charm whose chief attraction was perhaps its penetrating candor....[He] was swift-flowing and direct.... Acheson was perceived as an 18th century rationalist ready to apply an irreverent wit to matters public and private.[10]

The American occupation of Japan was nominally an Allied endeavor, but in practice it was run by General Douglas MacArthur, with little or no consultation with the Allies or with Washington. His responsibilities were enlarged to include the Korean War, till he broke with Truman on policy issues and was fired in highly dramatic fashion in 1951.[11] Policy for the occupation of West Germany was much less controversial, and the decisions were made in Washington, with Truman himself making the key decision to rebuild West Germany as an economic power.[12]

Roosevelt had handled all foreign policy decisions on his own, with a few advisors such as Harry Hopkins, who helped Truman too, even though he was dying of cancer. Roosevelt's final Secretary of State, Edward R. Stettinius was an amiable businessman who succeeded at reorganization of the department, and spent most of his attention in the creation of the United Nations. When that was accomplished, Truman replaced him with James F. Byrnes, whom Truman knew well from their Senate days together. Byrnes was more interested in domestic than foreign affairs, and felt he should have been FDR's pick for vice president in 1944. He was secretive, not telling Truman about major developments. Dean Acheson by this point was the number two person in State, and worked well with Truman. The president finally replaced Byrnes with Marshall. With the world in incredibly complex turmoil, international travel was essential. Byrnes spent 62% of his time abroad; Marshall spent 47% and Acheson 25%.[13]

End of World War II

By April 1945, the Allied Powers, led by the United States, Great Britain, and the Soviet Union, were close to defeating Germany, but Japan remained a formidable adversary in the Pacific War.[14] As vice president, Truman had been uninformed about major initiatives relating to the war, including the top-secret Manhattan Project, which was about to test the world's first atomic bomb.[15][16] Although Truman was told briefly on the afternoon of April 12 that the Allies had a new, highly destructive weapon, it was not until April 25 that Secretary of War Henry Stimson told him the details of the atomic bomb, which was almost ready.[17] Germany surrendered on May 8, 1945, ending the war in Europe. Truman's attention turned to the Pacific, where he hoped to end the war as quickly, and with as little expense in lives or government funds, as possible.[14]

With the end of the war drawing near, Truman flew to Berlin for the Potsdam Conference, to meet with Soviet leader Joseph Stalin and British leader Winston Churchill regarding the post-war order. Several major decisions were made at the Potsdam Conference: Germany would be divided into four occupation zones (among the three powers and France), Germany's border was to be shifted west to the Oder–Neisse line, a Soviet-backed group was recognized as the legitimate government of Poland, and Vietnam was to be partitioned at the 16th parallel.[18] The Soviet Union also agreed to launch an invasion of Japanese-held Manchuria.[19] While at the Potsdam Conference, Truman was informed that the Trinity test of the first atomic bomb on July 16 had been successful. He hinted to Stalin that the U.S. was about to use a new kind of weapon against the Japanese. Though this was the first time the Soviets had been officially given information about the atomic bomb, Stalin was already aware of the bomb project, having learned about it through espionage long before Truman did.[20]

In August 1945, the Japanese government ignored surrender demands as specified in the Potsdam Declaration. With the support of most of his aides, Truman approved the schedule of the military's plans to drop atomic bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Hiroshima was bombed on August 6, and Nagasaki three days later, leaving approximately 135,000 dead; another 130,000 would die from radiation sickness and other bomb-related illnesses in the following five years.[21] Japan agreed to surrender on August 10, on the sole condition that Emperor Hirohito would not be forced to abdicate; after some internal debate, the Truman administration accepted these terms of surrender.[22]

The decision to drop atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki provoked long-running debates.[23] Supporters of the bombings argue that, given the tenacious Japanese defense of the outlying islands, the bombings saved hundreds of thousands of lives that would have been lost invading mainland Japan.[24] After leaving office, Truman told a journalist that the atomic bombing "was done to save 125,000 youngsters on the American side and 125,000 on the Japanese side from getting killed and that is what it did. It probably also saved a half million youngsters on both sides from being maimed for life."[25] Truman was also motivated by a desire to end the war before the Soviet Union could invade Japanese-held territories and set up Communist governments.[26] Critics have argued that the use of nuclear weapons was unnecessary, given that conventional tactics such as firebombing and blockade might induce Japan's surrender without the need for such weapons.[27]

Postwar international order

Truman at first was committed to following Roosevelt's policies and priorities. He kept Roosevelt's cabinet for a short while before putting in his own people. In 1945 Truman repeatedly rejected Churchill's recommendations for a hard line against postwar Soviet expansion. Public opinion in America was demanding immediate demobilization of the troops. The policies followed were designed to benefit individuals, regardless of the damage it did when experienced military units lost their longest-serving and most experience soldiers. Truman refused to consider keeping an army in Europe for the purpose of neutralizing Stalin's expansion. [28] While Churchill and the U.S. State Department were taking an increasingly hard line, the War Department took a conciliatory position, led by Secretary Henry Stimson and General George Marshall. They rejected pleas and refused to allocate additional forces to Europe. In practice, the American forces were removed from Europe as fast as possible. [29]

By 1946, however, Truman had changed. Disappointed with Stalin and the United Nations, And alarmed about Soviet pressures on Iran and Poland, he was accepting more and more advice from the State Department and was moving rapidly toward Churchill's hard-line, Cold War position. The Soviet Union had become the enemy.[30]

United Nations

When Truman took office, several international organizations that were designed to help prevent future wars and international economic crises were in the process of being established.[14] Chief among those organizations was the United Nations, an intergovernmental organization similar to the League of Nations that was designed to help ensure international cooperation.[31] When Truman took office, delegates were about to meet at the United Nations Conference on International Organization in San Francisco.[32] As a Wilsonian internationalist, Truman strongly supported the creation of the United Nations, and he signed United Nations Charter at the San Francisco Conference. Truman did not repeat Woodrow Wilson's partisan attempt to ratify the Treaty of Versailles in 1919, instead cooperating closely with Senator Arthur H. Vandenberg and other Republican leaders to ensure ratification. Cooperation with Vandenberg, a leading figure on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, would be crucial for Truman's foreign policy, especially after Republicans gained control of Congress in the 1946 elections.[33][34] Construction of the United Nations headquarters in New York City was funded by the Rockefeller Foundation and completed in 1952.

Trade and refugees

In 1934, Congress had passed the Reciprocal Tariff Act, giving the president an unprecedented amount of authority in setting tariff rates. The act allowed for the creation of reciprocal agreements in which the U.S. and other countries mutually agreed to lower tariff rates.[35] Despite significant opposition from those who favored higher tariffs, Truman was able to win legislative extension of the reciprocity program, and his administration reached numerous bilateral agreements that lowered trade barriers.[36] The Truman administration also sought to further lower global tariff rates by engaging in multilateral trade negotiations, and the State Department proposed the establishment of the International Trade Organization (ITO). The ITO was designed to have broad powers to regulate trade among member countries, and its charter was approved by the United Nations in 1948. However, the ITO's broad powers engendered opposition in Congress, and Truman declined to send the charter to the Senate for ratification. In the course of creating the ITO, the U.S. and 22 other countries signed the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), a set of principles governing trade policy. Under the terms of the agreement, each country agreed to reduce overall tariff rates and to treat each co-signatory as a "most favoured nation," meaning that no non-signatory country could benefit from more advantageous tariff rates. Due to a combination of the Reciprocal Tariff Act, the GATT, and inflation, U.S. tariff rates fell dramatically between the passage of the Smoot–Hawley Tariff Act in 1930 and the end of the Truman administration in 1953.[35]

World War II left millions of refugees displaced in Europe. To help address this problem, Truman backed the founding of the International Refugee Organization (IRO), a temporary international organization that helped resettle refugees.[37] The United States also funded temporary camps and admitted large numbers of refugees as permanent residents. Truman obtained ample funding from Congress for the Displaced Persons Act of 1948, which allowed many of the displaced people of World War II to immigrate into the United States.[38] Of the approximately one million people resettled by the IRO, more than 400,000 settled in the United States. The most contentious issue facing the IRO was the resettlement of European Jews, many of whom, with the support of Truman, were allowed to immigrate to British-controlled Mandatory Palestine.[37] The administration also helped create a new category of refugee, the "escapee," at the 1951 Geneva Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees. The American Escapee Program began in 1952 to help the flight and relocation of political refugees from communism in Eastern Europe. The motivation for the refugee and escapee programs was twofold: humanitarianism, and use as a political weapon against inhumane communism.[39]

Atomic energy and weaponry

In March 1946, at an optimistic moment for postwar cooperation, the administration released the Acheson-Lilienthal Report, which proposed that all nations voluntarily abstain from constructing nuclear weapons. As part of the proposal, the U.S. would dismantle its nuclear program once all other countries agreed not to develop or otherwise acquire nuclear weapons. Fearing that Congress would reject the proposal, Truman turned to the well-connected Bernard Baruch to represent the U.S. position to the United Nations. The Baruch Plan, largely based on the Acheson-Lilienthal Report, was not adopted due to opposition from Congress and the Soviet Union. The Soviet Union would develop its own nuclear arsenal, testing a nuclear weapon for the first time in August 1949.[40]

The United States Atomic Energy Commission, directed by David E. Lilienthal until 1950, was in charge of designing and building nuclear weapons under a policy of full civilian control. The U.S. had only 9 atomic bombs in 1946, but the stockpile grew to 650 by 1951.[41] Lilienthal wanted to give high priority to peaceful uses for nuclear technology, especially nuclear power plants, but coal was cheap and the power industry was largely uninterested in building nuclear power plants during the Truman administration. Construction of the first nuclear plant would not begin until 1954.[42] In early 1950, Truman authorized the development of thermonuclear weapons, a more powerful version of atomic bombs. Truman's decision to develop thermonuclear weapons faced opposition from many liberals and some government officials, but he believed that the Soviet Union would likely develop the weapons and was unwilling to allow the Soviets to have such an advantage.[43] The first test of thermonuclear weaponry was conducted by the United States in 1952; the Soviet Union would perform its own thermonuclear test in August 1953.[44]

Beginning of the Cold War, 1945–1949

Escalating tensions, 1945–1946

The Second World War dramatically upended the international system, as formerly-powerful nations like Germany, France, Japan, and even Britain had been devastated. At the end of the war, only the United States and the Soviet Union had the ability to exercise influence, and a bipolar international power structure replaced the multipolar structure of the Interwar period.[45] On taking office, Truman privately viewed the Soviet Union as a "police government pure and simple," but he was initially reluctant to take a hard-line towards the Soviet Union, as he hoped to work with the Soviets in the aftermath of Second World War.[46] Truman's suspicions deepened as the Soviets consolidated their control in Eastern Europe throughout 1945, and the February 1946 announcement of the Soviet five-year plan further strained relations as it called for the continuing build-up of the Soviet military.[47] At the December 1945 Moscow Conference, Secretary of State Byrnes agreed to recognize the pro-Soviet governments in the Balkans, while the Soviet leadership accepted U.S. leadership in the occupation of Japan. U.S. concessions at the conference angered other members of the Truman administration, including Truman himself.[48] By the beginning of 1946, it had become clear to Truman that Britain and the United States would have little influence in Soviet-dominated Eastern Europe.[49]

Former Vice President Henry Wallace, former First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, and many other prominent Americans continued to hope for cooperative relations with the Soviet Union.[50] Some liberals, like Reinhold Niebuhr, distrusted the Soviet Union but believed that the United States should not try to counter Soviet influence in Eastern Europe, which the Soviets saw as their "strategic security belt."[51] Partly because of this sentiment, Truman was reluctant to fully break with the Soviet Union in early 1946,[50] but he took an increasingly hard line towards the Soviet Union throughout the year.[52] He personally approved of Winston Churchill's March 1946 "Iron Curtain" speech, which urged the United States to take the lead of an anti-Soviet alliance, though he did not publicly endorse it.[50]

Throughout 1946, tensions arose between the United States and the Soviet Union in places like Iran, which the Soviets had occupied during World War II. Pressure from the U.S. and the United Nations finally forced the withdrawal of Soviet soldiers.[53] Turkey also emerged as a point of contention, as the Soviet Union demanded joint control over the Dardanelles and the Bosphorus, key straits that controlled movement between the Black Sea and the Mediterranean Sea. The U.S. forcefully opposed this proposed alteration to the 1936 Montreux Convention, which had granted Turkey sole control over the straits, and Truman dispatched a fleet to the Eastern Mediterranean to show his administration's commitment to the region.[54] The Soviet Union and the United States also clashed in Germany, which had been divided into four occupation zones. In the September 1946 Stuttgart speech, Secretary of State Byrnes announced that the United States would no longer seek reparations from Germany and would support the establishment of a democratic state. The United States, France, and Britain agreed to combine their occupation zones, eventually forming West Germany.[55] In East Asia, Truman denied the Soviet request to reunify Korea, and refused to allow the Soviets a role in the post-war occupation of Japan.[56]

By September 1946, Truman was convinced that the Soviet Union sought world domination and that cooperation was futile.[57] He adopted a policy of containment, based on a 1946 cable by diplomat George F. Kennan.[58] Containment, a policy of preventing the further expansion of Soviet influence, represented a middle-ground position between friendly detente (as represented by Wallace), and aggressive rollback to regain territory already lost to Communism, as would be adopted in 1981 by Ronald Reagan.[59] Kennan's doctrine was based on the notion that the Soviet Union was led by an uncompromising totalitarian regime, and that the Soviets were primarily responsible for escalating tensions.[60] Wallace, who had been appointed Secretary of Commerce after the 1944 election, resigned from the cabinet in September 1946 due to Truman's hardening stance towards the Soviet Union.[61]

Truman Doctrine

In the first major step in implementing containment, Truman extended loans to Greece and Turkey to prevent the spread of Soviet-aligned governments.[62] Prior to 1947, the U.S. had largely ignored Greece, which had an anti-communist government, because it was under British influence.[63] Since 1944, the British had assisted the Greek government against a left-wing insurgency, but in early 1947 the British informed the United States that they could no longer afford to intervene in Greece. At the urging of Acheson, who warned that the fall of Greece could lead to the expansion of Soviet influence throughout Europe, Truman requested that Congress grant an unprecedented $400 million aid package to Greece and Turkey. In a March 1947 speech before a joint session of Congress, written by Acheson, Truman articulated the Truman Doctrine. It called for the United States to support "free people who are resisting attempted subjugation by armed minorities or by outside pressures." Overcoming isolationists who opposed involvement in Greek affairs, as well on the left who wanted cooperation with Moscow, Truman won bipartisan approval of the aid package.[64] The congressional vote represented a permanent break with the non-interventionism that had characterized U.S. foreign policy prior to World War II.[65]

The United States became closely involved in the Greek Civil War, which ended with the defeat of the insurgency in 1949. Stalin and Yugoslavian leader Josip Broz Tito both provided aid to the insurgents, but they fought for control causing a split in the Communist bloc.[66] American military and economic aid to Turkey also proved effective, and Turkey avoided a civil war.[67][68] The Truman administration also provided aid to the Italian government in advance of the 1948 general election where the Communists had strength. The aid package, combined with a covert CIA operation, anti-Communist mobilization by the Catholic Church and Italian Americans, helped to produce a Communist defeat.[69] The initiatives of the Truman Doctrine solidified the post-war division between the United States and the Soviet Union, and the Soviet Union responded by tightening its control over Eastern Europe.[70] Countries aligned with the Soviet Union became known as the Eastern Bloc, while the U.S. and its allies became known as the Western Bloc.

Although the far left element in the Democratic Party and the CIO was being expelled, some liberal Democrats opposed the Truman Doctrine. Eleanor Roosevelt wrote Truman in April 1947 calling him to rely on the United Nations instead of his Truman Doctrine. She denounced two Greece and Turkey because they were undemocratic and complained he was adopting “Mr. Churchill’s policies in the Near East.” Truman needed support from the Roosevelt wing, wrote her that while he held onto his long-term hopes for the United Nations, he insisted that and an "economically, ideologically and politically sound" peace would more likely come from American action, than from the United Nations. He emphasized the strategic geographical importance of the Greek-Turkish land bridge as a critical point in which democratic forces could stop the advance of communism that had so ravaged Eastern Europe.[71]

Military reorganization and budgets

| Fiscal Year | % GNP |

|---|---|

| 1945 | 38% |

| 1946 | 21% |

| 1948 | 5.0% |

| 1950 | 4.6% |

| 1952 | 13% |

Facing new, global challenges, the Truman administration reorganized the military and intelligence establishment to provide for more centralized control and reduce rivalries.[7] The National Security Act of 1947 combined and reorganized all military forces by merging the Department of War and the Department of the Navy into the National Military Establishment (which was later renamed as the Department of Defense). The law also created the U.S. Air Force, the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), and the National Security Council (NSC). The CIA and the NSC were designed to be non-military, advisory bodies that would increase U.S. preparation against foreign threats without assuming the domestic functions of the Federal Bureau of Investigation.[73] The National Security Act institutionalized the Joint Chiefs of Staff, which had been established on a temporary basis during World War II. The Joint Chiefs of Staff took charge of all military action, and the Secretary of Defense became the chief presidential adviser on military matter. In 1952, Truman secretly consolidated and empowered the cryptologic elements of the United States by creating the National Security Agency (NSA).[74] Truman also sought to require one year of military service for all young men physically capable of such service, but this proposal never won more than modest support among members of Congress.[75]

Truman had hoped that the National Security Act would minimize interservice rivalries, but each branch retained considerable autonomy and battles over the military budgets and other issues continued.[76] In 1949, Secretary of Defense Louis Johnson announced that he would cancel a so-called "supercarrier," which many in the navy saw as an important part of the service's future.[77] The cancellation sparked a crisis known as the "Revolt of the Admirals", when a number of retired and active-duty admirals publicly disagreed with the Truman administration's emphasis on less expensive strategic atomic bombs delivered by the air force. During congressional hearings, public opinion shifted strongly against the navy, which ultimately kept control of marine aviation but lost control over strategic bombing. Military budgets following the hearings prioritized the development of air force heavy bomber designs, and the United States accumulated a combat ready force of over 1,000 long-range strategic bombers capable of supporting nuclear mission scenarios.[78]

Following the end of World War II, Truman gave a low priority to defense budgets—it got whatever money was left over after domestic spending. From the beginning, he assumed that the American monopoly on the atomic bomb was adequate protection against any and all external threats.[79] Military spending plunged from 39% of GNP in 1945 to only 5% in 1948.[80][81][82] The number of military personnel fell from just over 3 million in 1946 to approximately 1.6 million in 1947, although the number of military personnel was still nearly five times larger than that of U.S. military in 1939.[83] In 1949, Truman ordered a review of U.S. military policies in light of the Soviet Union's acquisition of nuclear weapons. The National Security Council drafted NSC 68, which called for a major expansion of the U.S. defense budget, increased aid to U.S. allies, and a more aggressive posture in the Cold War. Despite increasing Cold War tensions, Truman dismissed the document, as he was unwilling to commit to higher defense spending.[84] The Korean War convinced Truman of the necessity for higher defense spending, and such spending would soar between 1949 and 1953.[85]

Marshall Plan

The Marshall Plan was launched by the United States in 1947-48 to replace numerous ad hoc loan and grant programs, with a unified, long-range plan to help restore the European economy, modernize it, remove internal tariffs and barriers, and encourage European collaboration. It was funded by the Republican -controlled Congress, where the isolationist Republican element was overwhelmed by a new internationalism. Stalin refused to let any of his satellite nations in Eastern Europe participate. Much less famous was a similar aid program aimed at Japan, China and other Asian countries. All the money was donated – there was no repayment needed. (At the same time, however, There were US government loan programs that did require repayment.)[86]

The United States had suddenly terminated the war-time Lend-Lease program in August 1945, to the surprise and distress of Britain, the Soviet Union and other nations. However the United States did send large sums and loans and relief supplies, though in an uncoordinated fashion with no long-term plan.[87] Western Europe was slowly recovering by 1947; Eastern Europe was being stripped of its resources by Moscow. Churchill warned that Europe was "a rubble heap, a charnel house, a breeding ground for pestilence and hate." American leaders feared that poor economic conditions could lead to Communism in France and Italy, where the far left was under Stalin's control. With the goal of containing Communism and increasing trade between the U.S. and Europe, the Truman administration devised the Marshall Plan. Dean Acheson was the key planner, But Marshall's an enormous worldwide prestige was used to sell the program at home and abroad. It sought to rejuvenate, Coordinate and modernize the economies of Europe. The Kremlin forced its satellites to reject Marshall Plan aid.[88] To fund the Marshall Plan, Truman asked Congress to approve an unprecedented, multi-year, $25 billion appropriation.[89] Congress, under the control of conservative Republicans, agreed to fund the program for multiple reasons. The 20-member conservative isolationist wing of the Republican Party, based in the rural Midwest, was led by Senator Kenneth S. Wherry. Wherry argued that it would be "a wasteful 'operation rat-hole'"; that it made no sense to oppose communism by supporting the socialist governments in Western Europe; and that American goods would reach Russia and increase its war potential. The isolationist bloc opposed loans or financial aid of any sort to Europe, opposed NATO, and tried to void presidential power to send troops to Europe. Their political base included many German-American and Scandinavian American communities that had suffered nasty attacks on their American patriotism during World War I. No matter what the issue, they could be counted on as vocal enemies of the Truman administration.[90] Wherry was outmaneuvered by the emerging internationalist wing in the Republican Party, led by Michigan Senator Arthur H. Vandenberg.[91]

With support from Republican Senator Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr., Vandenberg admitted there was no certainty that the plan would succeed, but said it would halt economic chaos, sustain Western civilization, and stop further Soviet expansion.[92] Senator Robert A. Taft, a leading conservative Republican who was generally skeptical of American commitments in Europe, chose to focus on domestic issues and deferred to Vandenberg on foreign policy.[93] Major newspapers were highly supportive, including pro-business conservative outlets like Time Magazine.[94][95] Both houses of Congress approved the initial appropriation, known as the Foreign Assistance Act, by large majorities, and Truman signed the act into law in April 1948.[96] Congress would eventually allocate $12.4 billion in aid over the four years of the plan.[97]

A new Washington agency the European Recovery Program (ERP) ran the Marshall Plan and close cooperation with the recipient nations. The money proved decisive, but the ERP was focused on a longer-range vision that included more efficiency, more high technology, and the removal of multiple internal barriers and tariffs inside Western Europe. ERP allowed each recipient to develop its own plan for the aid, it set several rules and guidelines on the use of the funding. Governments were required to exclude Communists, socialist policies were allowed, and balanced budgets were favored. Additionally, the ERP conditioned aid to the French and British on their acceptance of the reindustrialization of Germany and support for European integration. The Soviets set up their own program for aid, the Molotov Plan, and the new barriers reduced trade between the Eastern bloc and the Western bloc.[98]

The Marshall Plan helped European economies recover in the late 1940s and early 1950s. By 1952, industrial productivity had increased by 35 percent compared to 1938 levels. The Marshall Plan also provided critical psychological reassurance to many Europeans, restoring optimism to a war-torn continent. Though European countries did not adopt American economic structures and ideas to the degree hoped for by some Americans, they remained firmly rooted in mixed economic systems. The European integration process led to the creation of the European Economic Community, which eventually formed the basis of the European Union.[99]

Berlin airlift

In reaction to Western moves aimed at reindustrializing their German occupation zones, Stalin ordered a blockade of the Western-held sectors of Berlin, which was deep in the Soviet occupation zone. Stalin hoped to prevent the creation of a western German state aligned with the U.S., or, failing that, to consolidate control over eastern Germany.[100] After the blockade began on June 24, 1948, the commander of the American occupation zone in Germany, General Lucius D. Clay, proposed sending a large armored column across the Soviet zone to West Berlin with instructions to defend itself if it were stopped or attacked. Truman believed this would entail an unacceptable risk of war, and instead approved Ernest Bevin's plan to supply the blockaded city by air. On June 25, the Allies initiated the Berlin Airlift, a campaign that delivered food and other supplies, such as coal, using military aircraft on a massive scale. Nothing like it had ever been attempted before, and no single nation had the capability, either logistically or materially, to accomplish it. The airlift worked, and ground access was again granted on May 11, 1949. The Berlin Airlift was one of Truman's great foreign policy successes, and it significantly aided his election campaign in 1948.[101]

NATO

Rising tensions with the Soviets, along with the Soviet veto of numerous United Nations Resolutions, convinced Truman, Senator Vandenberg, and other American leaders of the necessity of creating a defensive alliance devoted to collective security.[102] In 1949, the United States, Canada, and several European countries signed the North Atlantic Treaty, creating a trans-Atlantic military alliance and committing the United States to its first permanent alliance since the 1778 Treaty of Alliance with France.[103] The treaty establishing NATO was widely popular and easily passed the Senate in 1949. NATO's goals were to contain Soviet expansion in Europe and to send a clear message to communist leaders that the world's democracies were willing and able to build new security structures in support of democratic ideals. The treaty also re-assured France that the United States would come to its defense, paving the way for continuing French cooperation in the re-establishment of an independent German state. The U.S., Britain, France, Italy, the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, Norway, Denmark, Portugal, Iceland, and Canada were the original treaty signatories.[104] Shortly after the creation of NATO, Truman convinced Congress to pass the Mutual Defense Assistance Act, which created a military aid program for European allies.[105]

Cold War tensions heightened following Soviet acquisition of nuclear weapons and the beginning of the Korean War. The U.S. increased its commitment to NATO, invited Greece and Turkey to join the alliance, and launched a second major foreign aid program with the passage of the Mutual Security Act. Truman permanently stationed 180,000 in Europe, and European defense spending grew from 5 percent to 12 percent of gross national product. NATO established a unified command structure, and Truman appointed General Dwight D. Eisenhower as the first Supreme Commander of NATO. West Germany, which fell under the aegis of NATO, would eventually be incorporated into NATO in 1955.[106]

Spain

Truman usually worked well with his top advisors--the exceptions were Israel in 1948 and Spain 1945-50. Truman was a very strong opponent of Francisco Franco, the right-wing dictator of Spain. He withdrew the American ambassador (but diplomatic relations were not formally broken), kept Spain out of the UN, and rejected any Marshall Plan financial aid to Spain. However, as the Cold War escalated, support for Spain was strong in Congress, the Pentagon, the business community and other influential elements especially Catholics and cotton growers. Liberal opposition to Spain had faded after the Wallace element broke with the Democratic Party in 1948; the CIO became passive on the issue. As Secretary of State Acheson increased his pressure on Truman, the president, stood alone in his administration as his own top appointees wanted to normalize relations. When China entered the Korean War and pushed American forces back, the argument for allies became irresistible. Admitting that he was "overruled and worn down," Truman relented and sent an ambassador and made loans available. Military talks began and President Eisenhower later brought Spain into NATO.[107]

Latin America

Cold War tensions and competition reached across the globe, affecting Europe, Asia, North America, Latin America, and Africa. The United States had historically focused its foreign policy on upholding the Monroe Doctrine in the Western Hemisphere, but new commitments in Europe and Asia diminished U.S. focus on Latin America. Partially in reaction to fears of expanding Soviet influence, the U.S. led efforts to create collective security pact in the Western Hemisphere. In 1947, the United States and most Latin American nations joined the Rio Pact, a defensive military alliance. The following year, the independent states of the Americas formed the Organization of American States (OAS), an intergovernmental organization designed to foster regional unity. Many Latin American nations, seeking favor with the United States, cut off relations with the Soviet Union.[108] Latin American countries also requested aid and investment similar to the Marshall Plan, but Truman believed that most U.S. foreign aid was best directed to Europe and other areas that could potentially fall under the influence of Communism.[109]

Asia

Recognition of Israel

Truman had long taken an interest in the history of the Middle East, and was sympathetic to Jews who sought a homeland in British-controlled Mandatory Palestine. In 1943, he had called for a homeland for those Jews who survived the Nazi regime. However, State Department officials were reluctant to offend the Arabs, who were opposed to the establishment of a Jewish state in the region. Secretary of Defense Forrestal warned Truman of the importance of Saudi Arabian oil in another war; Truman replied that he would decide his policy on the basis of justice, not oil. American diplomats with experience in the region were opposed, but Truman told them he had few Arabs among his constituents.[110] Regarding policy in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Middle East, Palestine was secondary to the goal of protecting the "Northern Tier" of Greece, Turkey, and Iran from communism.[111]

In 1947, the United Nations approved the partition of Mandatory Palestine into a Jewish state and an Arab state. The British announced that they would withdraw from Palestine in May 1948, and Jewish leaders began to organize a provisional government. In the months leading up to the British withdrawal, the Truman administration debated whether or not to recognize the fledgling state of Israel. Overcoming initial objections from Marshall, Clark Clifford convinced Truman that non-recognition would lead Israel to tilt towards the Soviet Union in the Cold War.[112] Truman recognized the State of Israel on May 14, 1948, eleven minutes after it declared itself a nation.[113] Israel would secure its independence with a victory in the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, but the Arab–Israeli conflict remains unresolved.[114]

China

Following the defeat of the Empire of Japan, China descended into a civil war. The civil war baffled Washington, as both the Nationalists under Chiang Kai-shek and the Communists under Mao Zedong had American advocates.[115] Truman sent George Marshall to China in early 1946 to broker a compromise featuring a coalition government. The mission failed, as both sides felt the issue would be decided on the battlefield, not at a conference table. Marshall returned to Washington in December 1946, blaming extremist elements on both sides.[116] In mid-1947, Truman sent General Albert Coady Wedemeyer to China to try again, but no progress was made.[117][118]

Though the Nationalists held a numerical advantage in the aftermath of the war, the Communists gained the upper hand in the civil war after 1947. Corruption, poor economic conditions, and poor military leadership eroded popular support for the Nationalist government, and the Communists won many peasants to their side. As the Nationalists collapsed in 1948, the Truman administration faced the question of whether to intervene on the side of the Nationalists or seek good relations with Mao. Chiang's strong support among sections of the American public, along with desire to assure other allies that the U.S. was committed to containment, convinced Truman to increase economic and military aid to the Nationalists. However, Truman held out little hope for a Nationalist victory, and he refused to send U.S. soldiers.[119]

In 1949 Mao Zedong and his Communists took control of the mainland of China, driving the Nationalists to Taiwan. The United States had a new enemy in Asia, and Truman came under fire from conservatives for "losing" China.[120] Along with the Soviet detonation of a nuclear weapon, the Communist victory in the Chinese Civil War played a major role in escalating Cold War tensions and U.S. militarization during 1949.[121] Truman would have been willing to maintain some relationship between the U.S. and the Communist government, but Mao was unwilling.[122] Chiang established the Republic of China on Taiwan, which retained China's seat on the UN Security Council until 1971.[123][124][a] In June 1950, after the outbreak of fighting in Korea, Truman ordered the Navy's Seventh Fleet into the Taiwan Strait to prevent further conflict between the communist government and the Republic of China.[125]

Japan

Under the leadership of General Douglas MacArthur, the U.S. occupied Japan after the latter's surrender in August 1945. MacArthur presided over extensive reforms of the Japanese government and society, implementing a new constitution that established a parliamentary democracy and granted women the right to vote. He also reformed the Japanese educational system and oversaw major economic changes, although Japanese business leaders were able to resist the reforms to some degree. As the Cold War intensified in 1947, the Truman administration took greater control over the occupation, ending Japanese reparations to the Allied Powers and prioritizing economic growth over long-term reform. The Japanese suffered from poor economic conditions until the beginning of the Korean War, when U.S. purchases stimulated growth.[126] In 1951, the United States and Japan signed the Treaty of San Francisco, which restored Japanese sovereignty but allowed the United States to maintain bases in Japan.[127] Over the opposition of the Soviet Union and some other adversaries of Japan in World War II, the peace treaty did not contain punitive measures such as reparations, though Japan did lose control of the Kuril Islands and other pre-war possessions.[128]

Southeast Asia

With the end of World War II, the United States fulfilled the commitment made by the 1934 Tydings–McDuffie Act and granted independence to the Philippines. The U.S. had encouraged decolonization throughout World War II, but the start of the Cold War changed priorities. The U.S. used the Marshall Plan to pressure the Dutch to grant independence to Indonesia under the leadership of the anti-Communist Sukarno, and the Dutch recognized Indonesia's independence in 1949. However, in French Indochina, the Truman administration recognized the French client state led by Emperor Bảo Đại. The U.S. feared alienating the French, who occupied a crucial position on the continent, and feared that the withdrawal of the French would allow the Communist faction of Ho Chi Minh to assume power.[129] Despite initial reluctance to become involved in Indochina, by 1952, the United States was heavily subsidizing the French suppression of Ho's Việt Minh in the First Indochina War.[85] The U.S. also established alliances in the region through the creation of the Mutual Defense Treaty with the Philippines and the ANZUS pact with Australia and New Zealand.[130]

Korean War

Outbreak of the war

Following World War II, the United States and the Soviet Union occupied Korea, which had been a colony of the Japanese Empire. The 38th parallel was chosen as a line of partition between the occupying powers since it was approximately halfway between Korea's northernmost and southernmost regions, and was always intended to mark a temporary separation before the eventual reunification of Korea.[131] Nonetheless, the Soviet Union established the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (North Korea) in 1948, while the United States established the Republic of Korea (South Korea) that same year.[132] Hoping to avoid a long-term military commitment in the region, Truman withdrew U.S. soldiers from the Korean Peninsula in 1949. The Soviet Union also withdrew their soldiers from Korea in 1949, but continued to supply North Korea with military aid.[133]

On June 25, 1950, Kim Il-sung's Korean People's Army invaded South Korea, starting the Korean War. In the early weeks of the war, the North Koreans easily pushed back their southern counterparts.[134] The Soviet Union was not directly involved, though Kim did win Stalin's approval before launching the invasion.[135] Truman, meanwhile, did not view Korea itself as a vital region in the Cold War, but he believed that allowing a Western-aligned country to fall would embolden Communists around the world and damage his own standing at home.[136] The top officials of the Truman administration were heavily influenced by a desire to not repeat the "appeasement" of the 1930s; Truman stated to an aide, "there's no telling what they'll do, if we don't put up a fight right now."[137] Truman turned to the United Nations to condemn the invasion. With the Soviet Union boycotting the United Nations Security Council due to the UN's refusal to recognize the People's Republic of China, Truman won approval of Resolution 84. The resolution denounced North Korea's actions and empowered other nations to defend South Korea.[136]

North Korean forces experienced early successes, capturing the city of Seoul on June 28. Fearing the fall of the entire peninsula, General Douglas MacArthur, commander of U.S. forces in Asia, won Truman's approval to land U.S. troops on the peninsula. Rather than asking Congress for a declaration of war, Truman argued that the UN Resolution provided the presidency the constitutional power to deploy soldiers as a "police action" under the aegis of the UN.[136] The intervention in Korea was widely popular in the United States at the time, and Truman's July 1950 request for $10 billion was approved almost unanimously.[138] By August 1950, U.S. troops pouring into South Korea, along with American air strikes, stabilized the front around the Pusan Perimeter.[139] Responding to criticism over unreadiness, Truman fired Secretary of Defense Louis Johnson and replaced him with the George Marshall. With UN approval, Truman decided on a "rollback" policy—conquest of North Korea.[140] UN forces launched a counterattack, scoring a stunning surprise victory with an amphibious landing at the Battle of Inchon that trapped most of the invaders. UN forces marched north, toward the Yalu River boundary with China, with the goal of reuniting Korea under UN auspices.[141]

Stalemate and dismissal of MacArthur

• North Korean, Chinese, and Soviet forces

• South Korean, U.S., Commonwealth, and United Nations forces

As the UN forces approached the Yalu River, the CIA and General MacArthur both expected that the Chinese would remain out of the war. Defying those predictions, Chinese forces crossed the Yalu River in November 1950 and forced the overstretched UN soldiers to retreat.[142] Fearing that the escalation of the war could spark a global conflict with the Soviet Union, Truman refused MacArthur's request to bomb Chinese supply bases north of the Yalu River.[143] UN forces were pushed below the 38th parallel before the end of 1950, but, under the command of General Matthew Ridgway, the UN launched a counterattack that pushed Chinese forces back up to the 38th parallel.[144]

MacArthur made several public demands for an escalation of the war, leading to a break with Truman in late 1950 and early 1951.[145] On April 5, House Minority Leader Joseph Martin made public a letter from MacArthur that strongly criticized Truman's handling of the Korean War and called for an expansion of the conflict against China.[146] Truman believed that MacArthur's recommendations were wrong, but more importantly, he believed that MacArthur had overstepped his bounds in trying to make foreign and military policy, potentially endangering the civilian control of the military. After consulting with the Joint Chiefs of Staff and members of Congress, Truman decided to relieve MacArthur of his command.[147] The dismissal of General Douglas MacArthur ignited a firestorm of outrage against Truman and support for MacArthur. Fierce criticism from virtually all quarters accused Truman of refusing to shoulder the blame for a war gone sour and blaming his generals instead. Others, including Eleanor Roosevelt, supported and applauded Truman's decision. MacArthur meanwhile returned to the U.S. to a hero's welcome, and addressed a joint session of Congress.[148] In part due to the dismissal of MacArthur, Truman's approval mark in February 1952 stood at 22% according to Gallup polls, which was, until George W. Bush in 2008, the all-time lowest approval mark for an active American president.[149] Though the public generally favored MacArthur over Truman immediately after MacArthur's dismissal, congressional hearings and newspaper editorials helped turn public opinion against MacArthur's advocacy for escalation.[150]

The war remained a frustrating stalemate for two years.[151] UN and Chinese forces fought inconclusive conflicts like the Battle of Heartbreak Ridge and the Battle of Pork Chop Hill, but neither side was able to advance far past the 38th parallel.[152] Throughout late 1951, Truman sought a cease fire, but disputes over prisoner exchanges led to the collapse of negotiations.[151] Of the 116,000 Chinese and Korean prisoners-of-war held by the United States, only 83,000 were willing to return to their home countries, and Truman was unwilling to forcibly return the prisoners.[153] The Korean War ended with an armistice in 1953 after Truman left office, dividing North Korea and South Korea along a border close to the 38th parallel.[154] Over 30,000 Americans and approximately 3 million Koreans died in the conflict.[155] The United States maintained a permanent military presence in South Korea after the war.[156]

International trips

Truman made five international trips during his presidency:[157] His only trans-Atlantic trip was to participate in the 1945 Potsdam Conference with British Prime Ministers Churchill and Attlee and Soviet Premier Stalin. He also visited neighboring Bermuda, Canada and Mexico, plus Brazil in South America. Truman only left the continental United States on two other occasions (to Puerto Rico, the Virgin Islands, Guantanamo Bay Naval Base, Cuba, February 20-March 5, 1948; and to Wake Island, October 11–18, 1950) during his nearly eight years in office.[158]

| Dates | Country | Locations | Details | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | July 16 – August 2, 1945 | Potsdam | Attended Potsdam Conference with British Prime Ministers Winston Churchill and Clement Attlee and Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin. | |

| August 2, 1945 | Plymouth | Informal meeting with King George VI. | ||

| 2 | August 23–30, 1946 | Hamilton | Informal visit. Met with Governor General Ralph Leatham and inspected U.S. military facilities. | |

| 3 | March 3–6, 1947 | Mexico, D.F. | State visit. Met with President Miguel Alemán Valdés. | |

| 4 | June 10–12, 1947 | Ottawa | Official visit. Met with Governor General Harold Alexander and Prime Minister Mackenzie King and addressed Parliament. | |

| 5 | September 1–7, 1947 | Rio de Janeiro | State visit. Addressed Inter-American Conference for the Maintenance of Continental Peace and Security and the Brazilian Congress. |

Legacy

Scholars have on average ranked Truman in the top ten American presidents, most often at #7. In 1962, a poll of 75 historians conducted by Arthur M. Schlesinger, Sr. ranked Truman among the "near great" presidents. Truman's ranking in polls of political scientists and historians, never fallen lower than ninth, and ranking as high as fifth in a C-SPAN poll in 2009.[159] A 2018 poll of the American Political Science Association’s Presidents and Executive Politics section ranked Truman as the seventh best president.[160] A 2017 C-Span poll of historians ranked Truman as the sixth best president.[161]

Truman was one of the most unpopular chief executives in U.S. history when he left office;[citation needed] in 1952, journalist Samuel Lubell stated that "after seven years of Truman's hectic, even furious, activity the nation seemed to be about on the same general spot as when he first came to office ... Nowhere in the whole Truman record can one point to a single, decisive break-through ... All his skills and energies—and he was among our hardest-working Presidents—were directed to standing still".[162] Nonetheless, Truman's image in university textbooks was quite favorable in the 1950s.[163] During the years of campus unrest in the 1960s and 1970s revisionist historians on the left attacked his foreign policy as too hostile to Communism, and his domestic policy as too favorable toward business.[164] That revisionism was not accepted by more established scholars.[165] The harsh perspective faded with the decline in Communism's appeal after 1980, leading to a more balanced view.[166][167] The fall of the Soviet Union in 1991 caused Truman advocates to claim vindication for Truman's decisions in the postwar period. According to Truman biographer Robert Dallek, "His contribution to victory in the cold war without a devastating nuclear conflict elevated him to the stature of a great or near-great president."[168] The 1992 publication of David McCullough's favorable biography of Truman further cemented the view of Truman as a highly regarded Chief Executive.[168] According to historian Daniel R. McCoy in his book on the Truman presidency,

Harry Truman himself gave a strong and far-from-incorrect impression of being a tough, concerned and direct leader. He was occasionally vulgar, often partisan, and usually nationalistic ... On his own terms, Truman can be seen as having prevented the coming of a third world war and having preserved from Communist oppression much of what he called the free world. Yet clearly he largely failed to achieve his Wilsonian aim of securing perpetual peace, making the world safe for democracy, and advancing opportunities for individual development internationally.[169]

See also

Notes

- ^ For the historiography see Brazinsky, Gregg (2012). "The Birth of a Rivalry: Sino‐American Relations during the Truman Administration". In Margolies, Daniel S. (ed.). A Companion to Harry S. Truman. pp. 484–497.

References

- ^ McCullough 1992, p. 366.

- ^ Andrew Alexander (2011). America and the Imperialism of Ignorance: US Foreign Policy Since 1945. p. 241. ISBN 9781849542579.

- ^ Michael F. Hopkins, "President Harry Truman's Secretaries of State: Stettinius, Byrnes, Marshall and Acheson." Journal of Transatlantic Studies 6.3 (2008): 290-304.

- ^ Robert L. Messer, The End of an Alliance: James F. Byrnes, Roosevelt, Truman, and the Origins of the Cold War (1982).

- ^ Frank W. Thackeray and John E. Findling, eds. Statesmen Who Changed the World: A Bio-Bibliographical Dictionary of Diplomacy (Greenwood, 1993) pp 337–45.

- ^ Gerald Pops, "The ethical leadership of George C. Marshall." Public Integrity 8.2 (2006): 165-185. Online

- ^ a b Herring 2008, pp. 613–614.

- ^ McCoy 1984, pp. 148–149.

- ^ Frank W. Thackeray and John E. Findling, eds. Statesmen Who Changed the World: A Bio-Bibliographical Dictionary of Diplomacy (Greenwood, 1993) pp 3-12.

- ^ Townsend Hoopes, "God and John Foster Dulles" Foreign Policy No. 13 (Winter, 1973-1974), pp. 154-177 at p 162

- ^ Michael Schaller, "MacArthur's Japan: The View from Washington." Diplomatic History 10.1 (1986): 1-23. online

- ^ Deborah Welch Larson, "The Origins of Commitment: Truman and West Berlin." Journal of Cold War Studies 13.1 (2011): 180-212.

- ^ Hopkins, "President Harry Truman’s Secretaries of State." p 293.

- ^ a b c McCoy 1984, pp. 21–22.

- ^ Barton J. Bernstein, "Roosevelt, Truman, and the atomic bomb, 1941-1945: a reinterpretation." Political Science Quarterly 90.1 (1975): 23-69.

- ^ Philip Padgett (2018). Advocating Overlord: The D-Day Strategy and the Atomic Bomb. U of Nebraska Press. p. cxv. ISBN 9781640120488.

- ^ Dallek 2008, pp. 19–20.

- ^ Robert Cecil, "Potsdam and its Legends." International Affairs 46.3 (1970): 455-465.

- ^ McCoy 1984, pp. 23–24.

- ^ John Lewis Gaddis, "Intelligence, espionage, and Cold War origins." Diplomatic History 13.2 (1989): 191-212.

- ^ Patterson 1996, pp. 108–111.

- ^ McCoy 1984, pp. 39–40.

- ^ Patterson 1996, p. 109.

- ^ "Review of: Thank God for the Atom Bomb, and Other Essays by Paul Fussell". PWxyz. Jan 1, 1988. Retrieved May 27, 2018.

Fussell, Paul (1988). "Thank God for the Atom Bomb". Thank God for the Atom Bomb and Other Essays. New York: Summit Books. - ^ Lambers, William (May 30, 2006). Nuclear Weapons. William K Lambers. p. 11. ISBN 0-9724629-4-5.

- ^ Herring 2008, pp. 591–593.

- ^ Kramer, Ronald C; Kauzlarich, David (2011), Rothe, Dawn; Mullins, Christopher W (eds.), "Nuclear weapons, international law, and the normalization of state crime", State crime: Current perspectives, pp. 94–121, ISBN 978-0-8135-4901-9.

- ^ Herbert Feis, Churchill, Roosevelt, Stalin: The war they waged and the peace they sought (1957) pp 599-600, 636-38, 652

- ^ Michael S. Sherry, Preparing for the War: American plans for postwar defense, 1941-45 (1977) pp, 180-185

- ^ Melvin P. Leffler, A preponderance of power: National security, the Truman administration, and the Cold War (1992) pp. 100–116.

- ^ Herring 2008, pp. 579–581.

- ^ Herring 2008, pp. 589–590.

- ^ Thomas Michael Hill, "Senator Arthur H. Vandenberg, the Politics of Bipartisanship, and the Origins of Anti-Soviet Consensus, 1941-1946." World Affairs 138.3 (1975): 219-241 in JSTOR.

- ^ Lawrence J. Haas, Harry and Arthur: Truman, Vandenberg, and the Partnership That Created the Free World (2016)

- ^ a b Irwin, Douglas A. (1998). "From Smoot-Hawley to Reciprocal Trade Agreements: Changing the Course of U.S. Trade Policy in the 1930s". In Bordo, Michael D.; Goldin, Claudia; White, Eugene N. (eds.). The Defining Moment: The Great Depression and the American Economy in the Twentieth Century. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9781479839902.

- ^ McCoy 1984, p. 270.

- ^ a b McCoy 1984, pp. 74–75.

- ^ "Harry S. Truman: Statement by the President Upon Signing the Displaced Persons Act". Presidency.ucsb.edu. Retrieved 2012-08-15.

- ^ Susan L. Carruthers, "Between Camps: Eastern Bloc 'Escapees' and Cold War Borderlands." American Quarterly 57.3 (2005): 911-942. online

- ^ Dallek 2008, pp. 49–50, 90.

- ^ Gregg Herken, The winning weapon: The atomic bomb in the cold war, 1945-1950 (1980)

- ^ Rebecca S. Lowen, "Entering the Atomic Power Race: Science, Industry, and Government." Political Science Quarterly 102.3 (1987): 459-479. in JSTOR

- ^ Patterson 1996, pp. 173–175.

- ^ Patterson 1996, pp. 175–176.

- ^ Herring 2008, pp. 595–596.

- ^ Dallek 2008, pp. 21–23.

- ^ Dallek 2008, pp. 28–29, 42.

- ^ Herring 2008, pp. 602–603.

- ^ McCoy 1984, pp. 78–79.

- ^ a b c Dallek 2008, pp. 43–44.

- ^ Patterson 1996, pp. 120–121.

- ^ Herring 2008, pp. 605–606.

- ^ Dallek 2008, pp. 44–45.

- ^ Herring 2008, pp. 609–610.

- ^ Herring 2008, pp. 608–609.

- ^ Patterson 1996, p. 116.

- ^ Herring 2008, pp. 610–611.

- ^ Dallek 2008, p. 43.

- ^ John Lewis Gaddis, Strategies of Containment: A Critical Appraisal of American National Security Policy during the Cold War (2nd ed. 2005).

- ^ Patterson 1996, p. 114.

- ^ Dallek 2008, pp. 46–48.

- ^ Herring 2008, pp. 614–615.

- ^ Dallek 2008, pp. 56–57.

- ^ Herring 2008, pp. 614–616.

- ^ Dallek 2008, pp. 58–59.

- ^ Herring 2008, pp. 616–617.

- ^ Joseph C. Satterthwaite, "The Truman doctrine: Turkey." The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 401.1 (1972): 74-84. online

- ^ Şuhnaz Yilmaz, Turkish-American Relations, 1800-1952: Between the Stars, Stripes and the Crescent (Routledge, 2015).

- ^ Herring 2008, p. 621.

- ^ Herring 2008, p. 622.

- ^ Elizabeth Spalding (2006). The First Cold Warrior: Harry Truman, Containment, and the Remaking of Liberal Internationalism. p. 75. ISBN 0813171288.

- ^ Kirkendall 1990, p. 237.

- ^ Dallek 2008, pp. 62–63.

- ^ Charles A. Stevenson (2008). "The Story Behind the National Security Act of 1947". Military Review. 88 (3).

- ^ McCoy 1984, pp. 117–118.

- ^ Patterson 1996, p. 133.

- ^ Patterson 1996, p. 168.

- ^ Keith McFarland, "The 1949 Revolt of the Admirals" Parameters: Journal of the US Army War College Quarterly (1980) 11#2 : 53–63. online Archived 2017-01-26 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Kirkendall 1990, p. 238.

- ^ Kirkendall 1990, pp. 237–239.

- ^ Paul Y. Hammond and Glenn H. Snyder, eds., Strategy, politics, and defense budgets (Columbia University Press, 1962).

- ^ Hogan 1998, pp. 83–85.

- ^ McCoy 1984, p. 116.

- ^ Herring 2008, pp. 637–639.

- ^ a b Herring 2008, p. 647.

- ^ Benn Steil, The Marshall Plan: Dawn of the Cold War (2018) excerpt.

- ^ McCoy 1984, pp. 71, 100.

- ^ Dallek 2008, pp. 60–61.

- ^ Herring 2008, pp. 617–619.

- ^ Bernard Lemelin, . "Isolationist Voices in the Truman Era: Nebraska Senators Hugh Butler and Kenneth Wherry." Great Plains Quarterly 37.2 (2017): 83-109.

- ^ Radmila Sergeevna Ayriyan, "Forming of the New System of International Relations: The Marshall Plan and Republican Party of the USA (1947-1948)." Middle-East Journal of Scientific Research 17.12 (2013): 1709-1713. online

- ^ John C. Campbell, The United States in World affairs: 1947-1948 (1948) pp 500-505.

- ^ Patterson 1996, p. 147.

- ^ Harold L. Hitchens, "Influences on the Congressional decision to pass the Marshall Plan." Western Political Quarterly 21.1 (1968): 51-68. in JSTOR

- ^ Diane B. Kunz, "The Marshall Plan reconsidered: a complex of motives." Foreign Affairs 76.3 (1997): 162-170

- ^ McCoy 1984, pp. 127–128.

- ^ Robert C. Grogin, Natural Enemies: The United States and the Soviet Union in the Cold War, 1917-1991 (2001) p.118

- ^ McCoy 1984, pp. 126–127.

- ^ Herring 2008, pp. 619–620.

- ^ Herring 2008, pp. 623–624.

- ^ Wilson D. Miscamble, "Harry S. Truman, the Berlin Blockade and the 1948 election." Presidential Studies Quarterly 10.3 (1980): 306-316. in JSTOR

- ^ McCoy 1984, pp. 139–140.

- ^ Dallek 2008, p. 89.

- ^ Dallek 2008, pp. 89–91.

- ^ McCoy 1984, pp. 198–201.

- ^ Herring 2008, pp. 645–649.

- ^ Mark S. Byrnes,"'Overruled and Worn Down': Truman Sends an Ambassador to Spain." Presidential Studies Quarterly 29.2 (1999): 263-279.

- ^ Herring 2008, pp. 626–627.

- ^ McCoy 1984, pp. 228–229.

- ^ McCullough 1992, pp. 595–97.

- ^ Michael Ottolenghi, "Harry Truman's recognition of Israel." Historical Journal (2004): 963-988.

- ^ Herring 2008, pp. 628–629.

- ^ Lenczowski 1990, p. 26.

- ^ Herring 2008, p. 629.

- ^ Warren I. Cohen, America's Response to China: A History of Sino-American Relations (4th ed. 2000) pp 151-72.

- ^ Forrest C. Pogue, George C. Marshall. vol 4. Statesman: 1945-1959 (1987) pp 51-143.

- ^ Yuwu Song, ed., Encyclopedia of Chinese-American Relations (McFarland, 2006), pp 59-62, 189-90, 290-95.

- ^ Roger B. Jeans, ed., The Marshall Mission to China, 1945–1947: The Letters and Diary of Colonel John Hart Caughey (2011).

- ^ Herring 2008, pp. 631–633.

- ^ Ernest R. May, "1947-48: When Marshall Kept the U.S. out of War in China." Journal of Military History (2002) 66#4: 1001-1010. online

- ^ Patterson 1996, p. 169–170.

- ^ June M. Grasso, Truman's Two-China Policy (1987)

- ^ Cochran, Harry Truman and the crisis presidency (1973) pp 291-310.

- ^ William W. Stueck, The road to confrontation: American policy toward China and Korea, 1947-1950. (U of North Carolina Press, 1981) online.

- ^ Donovan 1983, pp. 198–199.

- ^ Herring 2008, pp. 633–634.

- ^ Herring 2008, pp. 646–647.

- ^ McCoy 1984, pp. 271–272.

- ^ Herring 2008, pp. 634–635.

- ^ McCoy 1984, pp. 270–271.

- ^ Patterson 1996, p. 208.

- ^ Dallek 2008, p. 92.

- ^ Patterson 1996, p. 209.

- ^ McCoy 1984, pp. 222–27.

- ^ Patterson 1996, pp. 209–210.

- ^ a b c Dallek 2008, pp. 106–107.

- ^ Patterson 1996, p. 211.

- ^ Patterson 1996, pp. 214–215.

- ^ John J. Chapin (2015). Fire Brigade: U.S. Marines In The Pusan Perimeter. ISBN 9781786251619.

- ^ James I Matray, "Truman's Plan for Victory: National Self-Determination and the Thirty-Eighth Parallel Decision in Korea." Journal of American History 66.2 (1979): 314-333. in JSTOR

- ^ Stokesbury 1990, pp. 81–90.

- ^ Patterson 1996, pp. 219–222.

- ^ Dallek 2008, pp. 113.

- ^ Patterson 1996, pp. 225–226.

- ^ Patterson 1996, pp. 226–228.

- ^ Dallek 2008, pp. 117–118.

- ^ Dallek 2008, pp. 118–119.

- ^ Larry Blomstedt, Truman, Congress, and Korea: The Politics of America's First Undeclared War, University Press of Kentucky, 2015.

- ^ Paul J. Lavrakas (2008). Encyclopedia of Survey Research Methods. SAGE. p. 30. ISBN 9781506317885.

- ^ Patterson 1996, pp. 230–232.

- ^ a b Dallek 2008, p. 124.

- ^ Patterson 1996, p. 232.

- ^ Dallek 2008, p. 137.

- ^ Chambers II 1999, p. 849.

- ^ Herring 2008, p. 645.

- ^ Patterson 1996, p. 235.

- ^ "Travels of President Harry S. Truman". U.S. Department of State Office of the Historian.

- ^ "President Truman's Travel logs". The Harry S. Truman Library and Museum. Retrieved February 26, 2016.

- ^ see Associated Press, "List of Presidential rankings" Feb. 16, 2009.

- ^ Rottinghaus, Brandon; Vaughn, Justin S. (19 February 2018). "How Does Trump Stack Up Against the Best — and Worst — Presidents?". New York Times. Retrieved 14 May 2018.

- ^ "Presidential Historians Survey 2017". C-Span. Retrieved 14 May 2018.

- ^ Lubell, Samuel (1956). The Future of American Politics (2nd ed.). Anchor Press. pp. 9–10. OL 6193934M.

- ^ Robert Griffith, "Truman and the Historians: The Reconstruction of Postwar American History." Wisconsin Magazine of History (1975): 20-47.

- ^ See Barton J. Bernstein, ed., Politics and Policies of the Truman Administration (1970) pp 3-14.

- ^ Richard S. Kirkendall, The Truman period as a research field (2nd ed. 1974) p 14.

- ^ Kim Hakjoon (2015). "A Review of Korean War Studies Since 1992-1994". In Matray, James I. (ed.). Northeast Asia and the Legacy of Harry S. Truman: Japan, China, and the Two Koreas. p. 315.

- ^ Kent M. Beck, "What was Liberalism in the 1950s?." Political Science Quarterly 102.2 (1987): 233-258 at p 237.

- ^ a b Dallek 2008, p. 152.

- ^ McCoy 1984, pp. 318–19.

Works cited

- Chambers II, John W. (1999). The Oxford Companion to American Military History. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-507198-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Cohen, Eliot A.; Gooch, John (2006). Military Misfortunes: The Anatomy of Failure in War. New York: Free Press. ISBN 978-0-7432-8082-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Dallek, Robert (2008). Harry S. Truman. New York: Times Books. ISBN 978-0-8050-6938-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Donovan, Robert J. (1983). Tumultuous Years: 1949–1953. New York: W. W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-01619-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hamby, Alonzo L. (1995). Man of the People: A Life of Harry S. Truman. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-504546-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Herring, George C. (2008). From Colony to Superpower; U.S. Foreign Relations Since 1776. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-507822-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hogan, Michael J. (1998). A Cross of Iron: Harry S. Truman and the Origins of the National Security State, 1945-1954. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-79537-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kennedy, David M. (1999). Freedom from Fear: The American People in Depression and War, 1929–1945. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195038347.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kirkendall, Richard S. (1990). Harry S. Truman Encyclopedia. G. K. Hall Publishing.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lenczowski, George (1990). American Presidents and the Middle East. Durham: Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-0972-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - MacGregor, Morris J., Jr. (1981). Integration of the Armed Services 1940–1965. Washington, D.C.: Center of Military History. ISBN 978-0-16-001925-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - McCoy, Donald R. (1984). The Presidency of Harry S. Truman. University Press of Kansas.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - McCullough, David (1992). Truman. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-86920-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Patterson, James (1996). Grand Expectations: The United States 1945–1974. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195117974.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Stokesbury, James L. (1990). A Short History of the Korean War. New York: Harper Perennial. ISBN 978-0-688-09513-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Truman, Margaret (1973). Harry S. Truman. New York: William Morrow. ISBN 978-0-688-00005-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Weinstein, Allen (1997). Perjury: The Hiss-Chambers Case (revised ed.). Random House. ISBN 0-679-77338-X.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Further reading

- Beisner, Robert L. Dean Acheson: a life in the Cold War (2009). 800 pp. online free to borrow

- Beisner, Robert L. "Patterns of Peril: Dean Acheson Joins the Cold Warriors, 1945–46." Diplomatic History 1996 20(3): 321–355.

- Beschloss, Michael R. The Conquerors: Roosevelt, Truman and the Destruction of Hitler's Germany, 1941-1945 (2003) excerpt

- Bostdorff, Denise M. Proclaiming the Truman Doctrine: The Cold War Call to Arms (2008) excerpt

- Brinkley, Douglas, ed. Dean Acheson and the Making of U.S. Foreign Policy. 1993. 271 pp. essays by scholars

- Bryan, Ferald J. "George C. Marshall at Harvard: A Study of the Origins and Construction of the 'Marshall Plan' Speech." Presidential Studies Quarterly (1991): 489-502. Online

- Chace, James. Acheson: The Secretary of State Who Created the American World. (1998). 512 pp. online free to borrow

- Davis, Lynn Etheridge. The Cold War Begins: Soviet-American Conflict Over East Europe (Princeton UP, 2015.

- Divine, Robert A. "The Cold War and the Election of 1948," The Journal of American History, Vol. 59, No. 1 (Jun. 1972), pp. 90–110 in JSTOR

- Edwards, Lee. "Congress and the Origins of the Cold War: The Truman Doctrine," World Affairs, Vol. 151, 1989 online edition

- Feis, Herbert. Between War And Peace: The Potsdam Conference (1960), Pulitzer Prize Online

- Feis, Herbert. From trust to terror; the onset of the cold war, 1945-1950 (1970) online free to borrow

- Fletcher, Luke. "The Collapse of the Western World: Acheson, Nitze, and the NSC 68/Rearmament Decision." Diplomatic History 40#4 (2016): 750–777.

- Frazier, Robert. "Acheson and the Formulation of the Truman Doctrine." Journal of Modern Greek Studies 1999 17(2): 229–251. ISSN 0738-1727 in Project Muse

- Gaddis, John Lewis. "Reconsiderations: Was the Truman Doctrine a Real Turning Point?" Foreign Affairs 1974 52(2): 386–402.

- Gaddis, John Lewis. George F. Kennan: An American Life (2011).

- Geselbracht, Raymond H. ed. Foreign Aid and the Legacy of Harry S. Truman (2015).

- Graebner, Norman A. ed. An Uncertain Tradition: American Secretaries of State in the Twentieth Century (1961)

- Gusterson, Hugh. "Presenting the Creation: Dean Acheson and the Rhetorical Legitimation of NATO." Alternatives 24.1 (1999): 39-57.

- Harper, John Lamberton. American Visions of Europe: Franklin D. Roosevelt, George F. Kennan, and Dean G. Acheson. (Cambridge UP, 1994). 378 pp.

- Hasegawa, Tsuyoshi. Racing the Enemy: Stalin, Truman, and the Surrender of Japan (2009)

- Heiss, Mary Ann, and Michael J. Hogan, eds. Origins of the National Security State and the Legacy of Harry S. Truman (Kirksville: Truman State University Press, 2015(. xvi, 240 pp.

- Hinds, Lynn Boyd, and Theodore Otto Windt Jr. The Cold War as Rhetoric: The Beginnings, 1945–1950 (1991) online edition

- Holloway, David. Stalin and the Bomb: The Soviet Union and Atomic Energy 1939–1956 (Yale UP, 1994)

- Hopkins, Michael F. "President Harry Truman's Secretaries of State: Stettinius, Byrnes, Marshall and Acheson." Journal of Transatlantic Studies 6.3 (2008): 290-304.

- Hopkins, Michael F. Dean Acheson and the Obligations of Power (Rowman & Littlefield, 2017). xvi, 289 pp. Excerpt

- Isaacson, Walter, and Evan Thomas. The Wise Men: Six Friends and the World They Made (1997) 864pp; covers Dean Acheson, Charles E. Bohlen, W. Averell Harriman, George Kennan, Robert Lovett, and John J. McCloy; excerpt and text search

- Ivie, Robert L. "Fire, Flood, and Red Fever: Motivating Metaphors of Global Emergency in the Truman Doctrine Speech." Presidential Studies Quarterly 1999 29(3): 570–591. ISSN 0360-4918

- Judis, John B.: Genesis: Truman, American Jews, and the Origins of the Arab/Israeli Conflict. Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2014. ISBN 978-0-374-16109-5

- Leffler, Melvyn P. A preponderance of power: National security, the Truman administration, and the Cold War (Stanford UP,1992).

- Kepley, David R. The Collapse of the Middle Way: Senate Republicans and the Bipartisan Foreign Policy, 1948–1952 (1988)

- Lacey, Michael J. ed. The Truman Presidency (1989) ch 7-13. excerpt

- LaFeber, Walter (1993). America, Russia, and the Cold War, 1945–1992 (7th ed.). McGraw-Hill.

- Leffler, Melvyn P. For the Soul of Mankind: The United States, the Soviet Union, and the Cold War (2007)

- Levine, Steven I. "A New Look at American Mediation in the Chinese Civil War: the Marshall Mission and Manchuria." Diplomatic History 1979 3(4): 349–375. ISSN 0145-2096