People's Park (Berkeley)

| People's Park | |

|---|---|

People's Park, Berkeley | |

| Nearest city | Berkeley, California |

| Coordinates | 37°51′56″N 122°15′25″W / 37.86556°N 122.25694°W |

| Area | 2.8 acres (1.1 ha) |

| Created | April 20, 1969 |

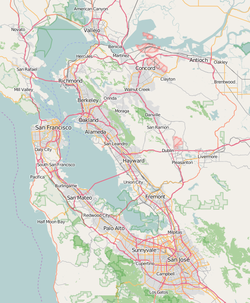

People's Park in Berkeley, California is a park located off Telegraph Avenue, bounded by Haste and Bowditch streets and Dwight Way, near the University of California, Berkeley. The park was created during the radical political activism of the late 1960s.[1][2][3][4]

The local Southside neighborhood was the scene of a major confrontation between student protesters and police in May 1969. A mural near the park, painted by Berkeley artist O'Brien Thiele and lawyer/artist Osha Neumann, depicts the shooting of James Rector, who was fatally shot by police on May 15, 1969.[5][6]

While legally the land is the property of the University of California, People's Park has operated since the early 1970s as a free public park. Although open to all, it is often viewed as a daytime sanctuary for Berkeley's low income and large homeless population who, along with others, receive meals from East Bay Food Not Bombs. Nearby residents, and those who try to use the park for recreation, sometimes experience conflict with the homeless people.[1][2][3][4]

Early history to May 1969

In 1956, the Regents of the University of California allocated a 2.8-acre (11,000 m2) plot of land containing residences for future development into student housing, parking, and offices as part of the university's "Long Range Development Plan." At the time, public funds were lacking to buy the land, and the plan was shelved until June 1967, when the university acquired $1.3 million to acquire the land through the process of eminent domain. The short-term goal was to create athletic fields with student housing being a longer-range goal.[7][8]

Bulldozers arrived February, 1968 and began demolition of the residences. But the university ran out of development funds, leaving the lot only partially cleared of demolition debris and rubble for 14 months. The muddy site became derelict with abandoned cars.[7][9]

On April 13, 1969, local merchants and residents held a meeting to discuss possible uses for the derelict site. At the time, student activist Wendy Schlesinger and Michael Delacour (a former defense contractor employee who had become an anti-war activist[10]) had become attached to the area, as they had been using it as a rendez-vous for a secret romantic affair.[7] The two presented a plan for developing the under-utilized, university-owned land into a public park. This plan was approved by the attendees, but not by the university. Stew Albert, a co-founder of the Yippie Party, agreed to write an article for the local counter-culture newspaper, the Berkeley Barb, on the subject of the park, particularly to call for help from local residents.[7]

A group of people took some corporate land, owned by the University of California, that was a parking lot and turned it into a park and then said, 'We're using the land better than you used it; it's ours.'

— Frank Bardacke, a participant in the park's development, quoted in the documentary film Berkeley in the Sixties[11]

Michael Delacour stated, "We wanted a free speech area that wasn't really controlled like Sproul Plaza [the plaza at the south entrance to UC Berkeley] was. It was another place to organize, another place to have a rally. The park was secondary."[12] The university's Free Speech microphone was available to all students, with few (if any) restrictions on speech. The construction of the park involved many of the same people and politics as the 1964 Free Speech Movement.[11]

On April 18, 1969, Albert's article appeared in the Berkeley Barb, and on Sunday, April 20, more than 100 people arrived at the site to begin building the park. Local landscape architect Jon Read and many others contributed trees, flowers, shrubs, and sod. Free food was provided, and community development of the park proceeded. Eventually, about 1,000 people became directly involved, with many more donating money and materials. The park was essentially complete by mid-May.[7][9][12]

On April 28, 1969, Berkeley Vice Chancellor Earl Cheit released plans for a sports field to be built on the site. This plan conflicted with the plans of the People's Park activists. However, Cheit stated that he would take no action without notifying the park builders.

Two days later, on April 30, Cheit allocated control over one quarter of the plot to the park's builders.

On May 6, Chancellor Roger W. Heyns met with members of the People's Park committee, student representatives, and faculty from the College of Environmental Design. He set a time limit of three weeks for this group to produce a plan for the park, and he reiterated his promise that construction would not begin without prior warning.[13]

On May 13, Chancellor Heyns notified media via a press release that the University would build a fence around the property and begin construction.[7]

May 15, 1969: "Bloody Thursday"

After its creation on April 20, during its first three weeks People's Park was used by both university students and local residents, and local Telegraph Avenue merchants voiced their appreciation for the community's efforts to improve the neighborhood.[9][14] Objections to the expropriation of university property tended to be mild, even among school administrators.

However, Governor Ronald Reagan had been publicly critical of university administrators for tolerating student demonstrations at the Berkeley campus.[15] He had received popular support for his 1966 gubernatorial campaign promise to crack down on what the public perceived as a generally lax attitude at California's public universities. Reagan called the Berkeley campus "a haven for communist sympathizers, protesters, and sex deviants."[15][16] Reagan considered the creation of the park a direct leftist challenge to the property rights of the university, and he found in it an opportunity to fulfill his campaign promise.

On Thursday, May 15, 1969 at 4:30 a.m., Governor Reagan sent California Highway Patrol and Berkeley police officers into People's Park, overriding Chancellor Heyns' May 6 promise that nothing would be done without warning. The officers cleared an 8-block area around the park while a large section of what had been planted was destroyed and an 8-foot (2.4 m)-tall perimeter chain-link wire fence was installed to keep people out and to prevent the planting of more trees, grass, flowers, or shrubs.[17]

The action came at the request of Berkeley's Republican mayor, Wallace Johnson.[18] It became the impetus for the "most violent confrontation in the university's history."[19]

Rally becomes protest

Beginning at noon on May 15,[17] about 3,000 people appeared in Sproul Plaza at nearby UC Berkeley for a rally, the original purpose of which was to discuss the Arab–Israeli conflict. Several people spoke; then, Michael Lerner ceded the Free Speech platform to ASUC Student Body President Dan Siegel because students were concerned about the fencing-off and destruction of the park. Siegel said later that he never intended to precipitate a riot; however, when he shouted "Let's take the park!,"[20] police turned off the sound system.[21] The crowd responded spontaneously, moving down Telegraph Avenue toward People's Park chanting, "We want the park!"[1]

Arriving in the early afternoon, protesters were met by the remaining 159 Berkeley and university police officers assigned to guard the fenced-off park site. The protesters opened a fire hydrant, several hundred protesters attempted to tear down the fence and threw bottles, rocks, and bricks at the officers, and then the officers fired tear gas canisters.[22] A major confrontation ensued between police and the crowd, which grew to 4,000.[23] Initial attempts by the police to disperse the protesters were not successful, and more officers were called in from surrounding cities. At least one car was set on fire.[22] A large group of protesters confronted a small group of sheriff's deputies who turned and ran. The crowd of protesters let out a cheer and briefly chased after them until the sheriff's deputies ran into a used car facility. The crowd then turned around and ran back to a patrol car which they overturned and set on fire.

Shooting

Reagan's Chief of Staff, Edwin Meese III, a former district attorney from Alameda County, had established a reputation for firm opposition to those protesting the Vietnam War at the Oakland Induction Center and elsewhere. Meese assumed responsibility for the governmental response to the People's Park protest, and he called in the Alameda County Sheriff's deputies, which brought the total police presence to 791 officers from various jurisdictions.[15]

Under Meese's direction, police were permitted to use whatever methods they chose against the crowds, which had swelled to approximately 6,000 people. Officers in full riot gear (helmets, shields, and gas masks) obscured their badges to avoid being identified and headed into the crowds with nightsticks swinging.[24]

"The indiscriminate use of shotguns [was] sheer insanity."

— Dr. Harry Brean, chief radiologist at Berkeley's Herrick Hospital[23]

As the protesters retreated, the Alameda County Sheriff's deputies pursued them several blocks down Telegraph Avenue as far as Willard Junior High School at Derby Street, firing tear gas canisters and "00" buckshot at the crowd's backs as they fled.

Authorities initially claimed that only birdshot had been used as shotgun ammunition. When physicians provided "00" pellets removed from the wounded as evidence that buckshot had been used,[25] Sheriff Frank Madigan of Alameda County justified the use of shotguns loaded with lethal buckshot by stating, "The choice was essentially this: to use shotguns—because we didn't have the available manpower—or retreat and abandon the City of Berkeley to the mob."[24] Sheriff Madigan did admit, however, that some of his deputies (many of whom were Vietnam War veterans) had been overly aggressive in their pursuit of the protesters, acting "as though they were Viet Cong."[26][27]

Casualties

Alameda County Sheriff's deputies also used shotguns to fire at people sitting on the roof at the Telegraph Repertory Cinema. James Rector was visiting friends in Berkeley and watching from the roof of Granma Books when he was shot by police;[28] he died on May 19.[6][29] The Alamada County Coroner's report listed cause of death as "shock and hemorrhage due to multiple shotgun wounds and perforation of the aorta." The buckshot is the same size as a .38 caliber bullet.[30] Governor Reagan conceded that Rector was probably shot by police but justified the bearing of firearms, saying that "it's very naive to assume that you should send anyone into that kind of conflict with a flyswatter. He's got to have an appropriate weapon."[31][32] The University of California Police Department (UCPD) claims Rector threw steel rebar down onto the police; however, according to Time, Rector was a bystander, not a protester.[27]

Carpenter Alan Blanchard was permanently blinded by a load of birdshot directly to his face.[27]

At least 128 Berkeley residents were admitted to local hospitals for head trauma, shotgun wounds, and other serious injuries inflicted by police. The actual number of seriously wounded was likely much higher, because many of the injured did not seek treatment at local hospitals to avoid being arrested.[7] Local medical students and interns organized volunteer mobile first-aid teams to help protesters and bystanders injured by buckshot, nightsticks, or tear gas. One local hospital reported two students wounded with large caliber rifles as well.[33]

News reports at the time of the shooting indicated that 50 were injured, including five police officers.[34] Some local hospital logs indicate that 19 police officers or Alameda County Sheriff's deputies were treated for minor injuries; none were hospitalized.[33] However, the UCPD claims that 111 police officers were injured, including one California Highway Patrol Officer Albert Bradley, who was knifed in the chest.[22]

State of emergency

POLICE SEIZE PARK;

SHOOT AT LEAST 35;

March Triggers Ave. Gassing;

Bystanders, Students Wounded;

Emergency, Curfew Enforced

— Front page headline of student newspaper The Daily Californian for May 16, 1969[35]

That evening, Governor Reagan declared a state of emergency in Berkeley and sent in 2,700 National Guard troops.[15][23] The Berkeley City Council symbolically voted 8–1 against the decision.[26][33] For two weeks, the streets of Berkeley were patrolled by National Guardsmen, who broke up even small demonstrations with tear gas.[24] Governor Reagan was steadfast and unapologetic: "Once the dogs of war have been unleashed, you must expect things will happen, and that people, being human, will make mistakes on both sides."[23]

During the People's Park incident, National Guard troops were stationed in front of Berkeley's empty lots to prevent protesters from planting flowers, shrubs, or trees. Young hippie women taunted and teased the troops, on one occasion handing out marijuana-laced brownies and lemonade spiked with LSD.[27] According to commanding Major General Glenn C. Ames, "LSD had been injected into fudge, oranges and apple juice which they received from young hippie-type females."[36] Some protesters, their faces hidden with scarves, challenged police and National Guard troops. Hundreds were arrested, and Berkeley citizens who ventured out during curfew hours risked police harassment and beatings.

Berkeley city police officers were discovered to be parking several blocks away from the Annex park, removing their badges and donning grotesque Halloween-type masks (including pig faces) to attack citizens they found in the park annex."[24]

Immediate aftermath

On Wednesday, May 21, 1969, a midday memorial was held for student James Rector at Sproul Plaza on the university campus, with several thousand people attending.

Demonstrations continued for several days after Bloody Thursday. A crowd of approximately 400 were driven from Sproul Plaza to Telegraph Avenue by tear gas on May 19.[37] On Thursday, May 22, 1969, about 250 demonstrators were arrested and charged with unlawful assembly; bail was set at $800 ($5,185 in 2014 dollars[38]).[39]

Showing solidarity with students, 177 faculty members said that they were "unwilling to teach until peace has been achieved by the removal of police and troops."[30] On May 23, the Berkeley faculty senate endorsed (642 to 95) a proposal by the College of Environmental Designs to have the park become the centerpiece of an experiment in community-generated design.[40]

In a separate university referendum, UC Berkeley students voted 12,719 to 2,175 in favor of keeping the park; the turnout represented about half of the registered student body.[40][41] Although Chancellor Heyns supported a proposal to lease the site to the city as a community park,[42] the Board of Regents voted to proceed with the construction of married student apartments in June 1969.[43]

Institutional responses

Law enforcement was using a new form of crowd control, pepper gas. The editorial offices of Berkeley Tribe were sprayed with pepper gas and had tear gas canisters fired into the offices, injuring underground press staff.

On May 20, 1969, National Guard helicopters flew over the Berkeley campus, dispensing airborne tear gas that winds dispersed over the entire city, sending school children miles away to hospitals. This was one of the largest deployments of tear gas during the Vietnam era protests.[44] Governor Reagan would concede that this might have been a "tactical mistake."[45] It had not yet been banned from warfare under the Chemical Weapons Convention.

The Washington Post wrote of the incident in an editorial: "[T]he indiscriminate gassing of a thousand people not at the time in violation of any law seems more than a little excessive." The editorial also criticized legislation before the U.S. House of Representatives that would have "cut off Federal aid to universities which fail to head off campus disorders."[46]

That legislation, the Higher Education Protection and Freedom of Expression Act of 1969 (Campus Disorder Bill, HR 11941, 91st Congress), was a response to mass protests and demonstrations at universities and colleges across the nation. It was introduced by House Special Subcommittee on Education chair Rep. Edith Green (D-OR). The bill would have required colleges and universities to file plans of action for dealing with campus unrest with the U.S. Commissioner of Education. The bill gave the institutions the power to suspend federal aid to students convicted—in court or by the university—of violating campus rules in connection with student riots. Any school that did not file such plans would lose federal funding.[47][48][49]

Governor Reagan supported the federal legislation; in a March 19, 1969 statement, he urged Congress to "be equally concerned about those who commit violence who are not receiving aid." On May 20, 1969, Attorney General John N. Mitchell advised the Committee that existing law was "adequate."[47] On June 13, Governor Reagan defended his actions in a televised speech delivered from San Francisco; public response was overwhelmingly supportive of the governor's actions.[50]

Peaceful protest

By May 26, the city-wide curfew and ban on gatherings had been lifted, although 200 members of the National Guard remained to guard the fenced-off park,[51] anticipating unrest from a march planned for May 30. Governor Reagan pledged that "whatever force is necessary will be on hand",[52] although protest leaders declared the march would be non-violent.[42]

On May 30, 1969, 30,000 Berkeley citizens (out of a population of 100,000) secured a city permit and marched without incident past the barricaded People's Park to protest Governor Reagan's occupation of their city, the death of James Rector, the blinding of Alan Blanchard, and the many injuries inflicted by police.[9] Young girls slid flowers down the muzzles of bayoneted National Guard rifles,[33] and a small airplane flew over the city trailing a banner that read, "Let A Thousand Parks Bloom."[9][53]

Nevertheless, over the next few weeks National Guard troops broke up any assemblies of more than four people who congregated for any purpose on the streets of Berkeley, day or night. In the early summer, troops deployed in downtown Berkeley surrounded several thousand protesters and bystanders, emptying businesses, restaurants, and retail outlets of their owners and customers, and arresting them en masse.

One year later

In an address before the California Council of Growers on April 7, 1970, almost a year after "Bloody Thursday" and the death of James Rector, Governor Reagan defended his decision to use the California National Guard to quell Berkeley protests: "If it takes a bloodbath, let's get it over with. No more appeasement."[54] Berkeley Tribe editors decided to issue this quote in large type on the cover of its next edition.[55][56][57][58]

Context

The May 1969 confrontation in People's Park grew out of the counterculture of the 1960s, pitting flower children against the Establishment.[41] Berkeley had been the site of the first large-scale antiwar demonstration in the country on September 30, 1964.[59]

Among the student protests of the late 1960s, the People's Park confrontation came after the 1968 protests at Columbia University and the Democratic National Convention, but before the Kent State killings and the burning of a branch of Bank of America in Isla Vista.[60] Closer to home, it occurred on the heels of the Stanford University April 3 movement, where students protested University-sponsored war-related research by occupying Encina Hall.[61]

Unlike other student protests of the late 1960s, most of which were at least partly in opposition to the U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War, the initial protests at People's Park were mostly in response to a local disagreement about land use.

1970s

After the peaceful march in support of People's Park on May 30, 1969, the university decided to keep the 8-foot-tall perimeter chain-link wire fence and maintain a 24-hour guard over the site. On June 20, the University of California Regents voted to turn the People's Park site into a soccer field and parking lot.[43]

In March 1971, when it seemed as though construction of the parking lot and soccer field might proceed, another People's Park protest occurred, resulting in 44 arrests.

In May 1972, an outraged crowd tore down the perimeter chain-link wire fence surrounding the People's Park site after President Richard Nixon announced his intention to mine North Vietnam's main port. In September, the Berkeley City Council voted to lease the park site from the university. The Berkeley community rebuilt the park, mainly with donated labor and materials. Various local groups contributed to managing the park during rebuilding.

In 1979, the university tried to convert the west end of the park, which was already a no-cost parking lot, into a fee lot for students and faculty only. The west end of the park was (and remains) the location of the People's Stage, a permanent bandstand that had just been erected on the edge of the lawn within the no-cost parking lot. Completed in the spring of 1979, it had been designed and constructed through user-development and voluntary community participation. This effort was coordinated by the People's Park Council, a democratic group of park advocates, and the People's Park Project/Native Plant Forum. Park users and organizers believed that the university's main purpose in attempting to convert the parking lot was the destruction of the People's Stage in order to suppress free speech and music, both in the park and in the neighborhood south of campus as a whole. It was also widely believed that the foray into the west end warned of the dispossession of the entire park for the purpose of university construction. A spontaneous protest in the fall of 1979 led to an occupation of the west end that continued uninterrupted throughout December 1979. Park volunteers tore up the asphalt and heaped it up as barricades next to the sidewalks along Dwight Way and Haste Street. This confrontation led to negotiations between the university and the park activists. The park activists were led by the People's Park Council, which included park organizers and occupiers, as well as other community members. The university eventually capitulated. Meanwhile, the occupiers, organizers, and volunteer gardeners transformed the former parking lot into a newly cultivated organic community gardening area, which remains to this day.

People's Park Annex/Ohlone Park

The Bay Area Rapid Transit has substantial property under which the new San Francisco trains will run. The surface has been offered to the city, without charge, for such a park and is located only a few blocks away from this park. Actually, the space available for a park there is substantially larger. If the real issue is a park for people, why not develop that?

— State Sen. Gordon Cologne, June 1969 editorial, The Desert Sun[62]

In the immediate aftermath of the May 1969 People's Park demonstrations, and consistent with their goal of "letting a thousand parks bloom," on May 25,[51][63] People's Park activists began gardening a two-block strip of land called the "Hearst Corridor," located adjacent to Hearst Avenue just northwest of the university campus. The Hearst Corridor was a strip of land along the north side of Hearst Avenue that had been left largely untended after the houses had been torn down to facilitate completion of an underground subway line by the Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) District. Although BART officials offered to lease the site to the city for a park,[64] on the night of June 6, approximately 400 people were forcibly evicted from what was then called "People's Park No. 2" by Berkeley police, who also removed playground equipment and trees that had been recently planted.[65]

During the 1970s, local residents, especially George Garvin, pursued gardening and user development of this land, which became known as "People's Park Annex." Later on, additional volunteers donated time and energy to the Annex, led by David Axelrod and Charlotte Pyle, urban gardeners who were among the original organizers of the People's Park Project/Native Plant Forum.

As neighborhood and community groups stepped up their support for the preservation and development of the Annex, BART abandoned its original plan to build apartment complexes on Hearst Corridor. The City of Berkeley negotiated with BART to secure permanent above-ground rights to the entire five block strip of land, between Martin Luther King Jr. Way and Sacramento Avenue. By the early 1980s, this land had become a city park comprising 9.8 acres (40,000 m2), which residents decided to name "Ohlone Park" in honor of the Ohlone band of Native Americans who once lived there.

Today, the Berkeley Parks and Recreation Commission mediates neighborhood and community feedback concerning issues of park design and the maintenance, operation, and development of Ohlone Park amenities. These amenities—which include pedestrian and bicycle paths, children's playgrounds, a dog park, basketball and volleyball courts, a softball/soccer field, toilets, picnic areas, and community gardens—continue to serve the people and pets of Berkeley.

Subsequent history

The park has seen various projects come and go over the decades. The "Free Box" operated as a clothes donation dropoff site for many years until it was destroyed by arson in 1995. Subsequent attempts to rebuild it were dismantled by University police.

The university built sand volleyball courts at the south end of the park in 1991. Protesters demonstrated against the project, at times sitting on the volleyball courts to prevent their use. The courts eventually were dismantled in 1997.

In 2011, People's Park saw a new wave of protests, known as the "tree-sit." It consisted of a series of individual "tree-sitters" who occupied a wooden platform in one of the trees in People's Park. The protests were troubled by abrupt interruptions and altercations. One protester was arrested,[66] another fell from the tree while sleeping.[67] But despite the transitions and overlapping political platforms, such as the 10 PM curfew[68] and the university's plans for development, the protests lasted throughout most of the fall of 2011. The tree-sits were also supported by Zachary RunningWolf, a Berkeley activist and several-time mayoral candidate, who actively spoke to the media about the protesters and the causes they were championing.[66] RunningWolf claimed that the central motive for the protests was to demonstrate that "poverty is not a crime."[67]

Despite the protests, in late 2011, UC Berkeley bulldozed the west end of People's Park, tearing up the decades-old community garden and plowing down mature trees in what a press release issued by the school described as an effort to provide students and the broader community with safer, more sanitary conditions.[69][70] This angered some Berkeley students and residents, who noted that the bulldozing took place during winter break when many students were away from campus, and followed the administration-backed police response at Occupy Cal less than two months prior.

People's Park has been the subject of long-running contention between those who see it as a memorial to the Free Speech Movement and a haven for the poor; and those who describe it as crime-infested and unfriendly to families. While the park has public bathrooms, gardens, and a playground area, many residents do not see it as a welcoming place, citing drug use and a high crime rate.[71] A San Francisco Chronicle article on January 13, 2008 referred to People's Park as "a forlorn and somewhat menacing hub for drug users and the homeless." The same article quoted denizens and supporters of the park saying it was "perfectly safe, clean and accessible."[72] In May 2018, UC Berkeley reported that campus police had been called 1,585 times to People's Park in the previous year.[73] The University also said there had been 10,102 criminal incidents in the park between 2012 and 2017.[74]

Proposed development

In 2018, UC Berkeley unveiled a plan for People's Park that would include the construction of housing for as many as 1,000 students, supportive housing for the homeless or military veterans, and a memorial honoring the park's history and legacy.[73][74][75][76] On August 29, 2019, Chancellor Carol T. Christ confirmed plans to create student housing for 600-1000 students, and supportive housing for 100-125 people. San Francisco-based LMS architects has been selected to build the housing, and Christ stated that they are moving to a time of "extensive public comment" on the plans for construction.[77]

Some critics state that any attempts to construct student housing will "inevitably be met with incandescent violence." Going further to describe it as "a shit show that will make the 1969 and 1991 riots look like an afternoon soiree of tea and crumpets." [78]

See also

Notes

- ^ a b c Tempest, Rone (December 4, 2006). "It's Still a Batlefield". L. A. Times. Retrieved February 5, 2013.

- ^ a b Meyers, Jessica (2006-09-12). "A Portrait of People's Park". Northgate News Online. Archived from the original on 2008-08-04. Retrieved 2008-03-11.

- ^ a b Wagner, David (May 5, 2008). "Hip-Hop Festival Takes Over People's Park". The Daily Californian. Archived from the original on January 6, 2016.

- ^ a b Gross, Rachel (January 26, 2009). "Residents, Homeless Try to Coexist by People's Park". The Daily Californian. Archived from the original on January 6, 2016.

- ^ "A People's History of Telegraph Avenue". Berkeley Historical Plaque Project. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- ^ a b Whiting, Sam (May 13, 2019). "People's Park at 50: a recap of the Berkeley struggle that continues". SFChronicle.com. Retrieved 2020-05-01.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b c d e f g Brenneman, Richard (April 20, 2004). "The Bloody Beginnings of People's Park". The Berkeley Daily Planet. Retrieved July 23, 2008.

- ^ Retired Lieutenant John E. Jones (August 2006). "A Brief History of University of California Police Department, Berkeley". Archived from the original on 10 December 2015. Retrieved 9 October 2014.

- ^ a b c d e Lowe, Joan. "People's Park, Berkeley". Stories from the American Friends Service Committee's Past. Archived from the original on 2008-02-13. Retrieved 2008-03-11.

- ^ "People's Park Fights UC Land Use Policy; One Dead, Thousands Tear Gassed". Picture This: California's Perspectives on American History. Oakland Museum of California. Retrieved 11 November 2014.

- ^ a b Kitchell, Mark (Director and Writer) (January 1990). Berkeley in the Sixties (Documentary). Liberation. Retrieved 2008-03-11.

- ^ a b Wittmeyer, Alicia (2004-04-26). "From Rubble to Refuge". The Daily Californian. Retrieved 2008-03-11.

- ^ "Chronology of People's Park – The Old Days". peoplespark.org. Retrieved 2008-03-11.

- ^ Winner, Langdon. "What's Next – Bombs?". Archived from the original on September 2, 2007. Retrieved February 16, 2007.

- ^ a b c d Rosenfeld, Seth (June 9, 2002). "Part 4: The governor's race". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved July 23, 2008.

- ^ Jeffery Kahn (8 June 2004). "Ronald Reagan launched political career using the Berkeley campus as a target". Retrieved 9 October 2014.

- ^ a b "Patrolling Site of Riot: National Guard in Berkeley; 128 Persons Injured In Street Fighting". The Desert Sun. UPI. May 16, 1969. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- ^ Cobbs-Hoffman, Blum & Gjerde 2012, p. 423.

- ^ Oakland Museum of California (n.d.). "People's Park Fights UC Land Use Policy; One Dead, Thousands Tear Gassed". Retrieved 9 October 2014.

- ^ However, another publisher claims that what he said was, "I have a suggestion. Let's go down to the People's Park–". Retrieved November 6, 2008.

- ^ "People's History of Berkeley". Barrington Collective. Archived from the original on August 3, 2007. Retrieved February 26, 2007.

- ^ a b c Jones, John, UCPD Berkeley: History Topic: People's Park, UCPD Berkeley, archived from the original on 2015-12-10, retrieved 2008-11-06

- ^ a b c d Elizabeth Cobbs-Hoffman; Edward Blum; Jon Gjerde (2012). Major Problems in American History, Volume II: Since 1865, third edition. Wadsworth. ISBN 978-1111343163. Retrieved 9 October 2014.

- ^ a b c d "Sheriff Frank Madigan". Berkeley Daily Gazette. May 30, 1969.

- ^ "The Battle of People's Park". Archived from the original on August 30, 2007. Retrieved February 16, 2007.

- ^ a b "People's Park". Archived from the original on February 10, 2012. Retrieved February 16, 2007.

- ^ a b c d "California: Postscript to People's Park". Time. February 16, 1970. Retrieved July 23, 2008.

- ^ "James Rector, Wounded on the roof of Granma Books". Berkeley Revolution. May 15, 1969. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- ^ "Berkeley Riot Victim Succumbs in Hospital". The Desert Sun. UPI. May 20, 1969. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- ^ a b Gustaitis, Rasa (May 21, 1969). "Confrontation at Berkeley Turns Into Calm Songfest". The Washington Post. pp. A12.

- ^ Gustaitis, Rasa (May 21, 1969). "Helicopter Sprays Gas On Berkeley 'Mourners': Guardsman Led Away". The Washington Post. pp. A6.

- ^ "Reagan Blames Berkeley Violence On 'Revolutionaries'". The California Aggie. May 23, 1969. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- ^ a b c d Smitha, Frank E. "The Sixties and Seventies from Berkeley to Woodstock". Microhistory and World Report. Retrieved July 23, 2008.

- ^ Gustaitis, Rasa (May 16, 1969). "50 Are Injured In Berkeley Fray". The Washington Post. pp. A3.

- ^ Pichirallo, Joe (May 16, 1969). "POLICE SEIZE PARK; SHOOT AT LEAST 35". The Daily Californian.

- ^ "National Guard Given LSD by Hippie Girls". San Bernardino Sun. AP. May 20, 1969. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- ^ "UC Plaza Crowd Scattered by Gas". San Bernardino Sun. AP. May 20, 1969. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- ^ "BLS inflation calculator". Retrieved 9 October 2014.

- ^ "250 Seized in Berkeley Park Clash". The Washington Post. May 23, 1969. pp. A4.

- ^ a b Gustaitis, Rasa (May 24, 1969). "Faculty at Berkeley Votes For 'Park' as Experiment". The Washington Post. pp. A6.

- ^ a b "Occupied Berkeley". Time Magazine. Time Inc. May 30, 1969. Retrieved January 14, 2007.

- ^ a b "Berkeley Faces New Crisis: New Confrontation Threatened Today At People's Park". The Desert Sun. UPI. May 30, 1969. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- ^ a b "'People's Park' To Get Housing". The Desert Sun. UPI. June 21, 1969. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- ^ Anna Feigenbaum (16 August 2014). "100 Years of Tear Gas". The Atlantic. Retrieved 9 October 2014.

- ^ AP (22 May 1969). "UC Professors Confront Reagan". Vol. 55, no. 65. Retrieved 9 October 2014.

- ^ Editorial (May 24, 1969). "Fanning the Fire". The Washington Post. pp. A14.

- ^ a b "Campus Disorder Bill". CQ Almanac 1969 (25th ed.). Washington, DC: Congressional Quarterly: 726–29. 1970. Retrieved 9 October 2014.

- ^ Smith, Francis (1970). "Campus Unrest: Illusion and Reality". William & Mary Law Review. 11 (3). Retrieved 9 October 2014.

- ^ Keeney, Gregory (1970). "Aid to education, student unrest, and cutoff legislation: an overview". University of Pennsylvania Law Review. 119 (6): 1003–1034. doi:10.2307/3311201. JSTOR 3311201. Retrieved 9 October 2014.

- ^ "California 33-to-1 for Reagan on People's Park". The Desert Sun. June 18, 1969. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- ^ a b "Curfew, Gathering Ban Lifted". The Desert Sun. UPI. May 26, 1969. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- ^ "Reagan Pledges Required Force". The Desert Sun. UPI. May 28, 1969. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- ^ "UC Berkeley Grapples Again with a Troubled People's Park". North Gate News Online. September 21, 2006. Archived from the original on March 9, 2012. Retrieved May 14, 2013.

- ^ Lou Cannon (2003). Governor Reagan: His Rise to Power. Public Affairs. p. 295. ISBN 1-58648-284-X. Retrieved 2008-03-10.

- ^ Rips, Geoffrey. "The Campaign Against the Underground Press". History is a Weapon.

- ^ Peck, Abe (1985). Uncovering the Sixties: the life and times of the underground press (1st ed.). New York: Pantheon Books. pp. 278–279, 288. ISBN 9780394527932.

- ^ Armstrong, David (1981). A Trumpet to Arms: Alternative Media in America (1st ed.). Boston, Massachusetts: South End Press. p. 175. ISBN 9780896081932.

- ^ Zald, Anne E.; Whitaker, Cathy Seitz (1 January 1990). "The underground press of the Vietnam era: An annotated bibliography". Reference Services Review. 18 (4): 76–96. doi:10.1108/eb049109.

- ^ First large scale antiwar demonstration staged at Berkeley, This Day In History, retrieved 9 October 2014

- ^ Lodise, Carmen (2002). A People's History of Isla Vista.

- ^ "The Troubles at Stanford: Student Uprisings in the 1960s and '70s" (PDF), Sandstone & Tile, 35 (1), Winter 2011, archived from the original (PDF) on 16 October 2014, retrieved 9 October 2014

- ^ Cologne, Gordon (June 11, 1969). "Stand Against Such a Give-Away". The Desert Sun. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- ^ "New Site For People's Park Developing". Desert Sun. UPI. May 26, 1969. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- ^ "Talk Replaces Violence In Berkeley". Santa Cruz Sentinel. AP. June 4, 1969. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- ^ "People's Park No. 2 — New Berkeley Unrest: Police Evict 400 From New Site; Break Up Parade". Desert Sun. UPI. June 7, 1969. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- ^ a b "Tree-sitter renews People's Park protest | The Daily Californian". The Daily Californian. 2011-08-29. Retrieved 2018-05-04.

- ^ a b "Tree-sitter falls from tree, protest ends | The Daily Californian". The Daily Californian. 2011-09-07. Retrieved 2018-05-04.

- ^ "People's Park tree-sitter preaches park issues to passersby | The Daily Californian". The Daily Californian. 2011-09-30. Retrieved 2018-05-04.

- ^ Sciacca, Annie (23 January 2012). "Contention resurfaces with People's Park maintenance project". DailyCal.org. The Daily Californian (UC Berkeley). Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- ^ Denney, Carol (December 28, 2011). "Flash: UC Berkeley Bulldozes People's Park to Make It More 'Sanitary'". The Berkeley Daily Planet.

- ^ Keith, Tamara (April 14, 1999). "People's Park Is Melting in the Dark..." The Berkeleyan. The Regents of the University of California. Retrieved 2007-02-11.

- ^ Jones, Carolyn (January 13, 2008). "UC Berkeley seeks public's views to plan new path for People's Park". San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ a b "New UC Berkeley plans for People's Park call for student, homeless housing". berkeley.edu/news. University of California, Berkeley. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- ^ a b Dinkelspiel, Frances. "UC Berkeley confirms that a dorm for 1K students will be built in People's Park". Berkeleyside.com. Berkeleyside. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- ^ Asimov, Nanette. "UC Berkeley's plans for People's Park include five-story building plus memorial". sfchronicle.com. San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- ^ Watanabe, Teresa. "On the grounds of People's Park, UC Berkeley proposes housing for students and the homeless". latimes.com. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- ^ Orenstein, Natalie (2019-08-30). "UC Berkeley forges ahead with housing at People's Park, other sites". Berkeleyside. Retrieved 2019-08-31.

- ^ "THE LONG HAUL – Opposing All States Since the Existence of States". thelonghaul.org. Retrieved 2018-08-11.

References

- California Governor's Office. The "People's Park" - A Report on the Confrontation at Berkeley, California. Submitted to Gov. Ronald Reagan. July 1, 1969.

- Gruen, Gruen and Associates. Southside Student Housing Project Preliminary Environmental Study. Report to UCB Chancellor. February 1974.

- People's Park Handbills. Distributed May–April 1969. Located at the Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

- Pichirall, Joe. The Daily Californian. Cover Story on People's Park. May 16, 1969.

- "Reagan's Reaction to Riot: Call Park Here 'Excuse'" The Daily Californian. May 16, 1969.

- Statement on People's Park. University of California, Berkeley – Office of Public Information. April 30, 1969.

- Weiss, Norman. The Daily Californian. "People's Park: Then & Now." March 17, 1997.

Further reading

- Compost, Terri (ed.) (2009) People's Park: Still Blooming. Slingshot! Collective. ISBN 9780984120802. Includes original photos and materials.

- Dalzell, Tom (Foreword by Todd Gitlin, Afterword by Steve Wasserman) (2019) Battle for People's Park, Berkeley 1969. Heyday Books ISBN 9781597144681. Eyewitness testimonies and hundreds of remarkable, often previously unpublished photographs.

- Rorabaugh, W. J. Berkeley at War: The 1960s (1990)

External links

- Parks in Berkeley, California

- Guerrilla gardening

- History of Berkeley, California

- University of California, Berkeley

- Culture of Berkeley, California

- Crime in the San Francisco Bay Area

- Police brutality in the United States

- Military history of California

- Military in the San Francisco Bay Area

- Politics of the San Francisco Bay Area

- 1969 in California

- Tourist attractions in Berkeley, California

- Riots and protests at UC Berkeley

- Protests in the San Francisco Bay Area