Desfontainia

| Desfontainia | |

|---|---|

| |

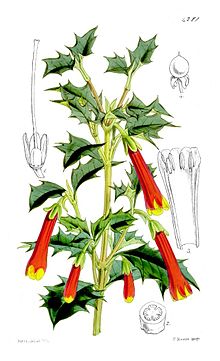

| Desfontainia spinosa[1] | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Asterids |

| Order: | Bruniales |

| Family: | Columelliaceae |

| Genus: | Desfontainia Ruiz & Pav. 1794 |

| Type species | |

| Desfontainia spinosa | |

Desfontainia is a genus of flowering plants placed currently in the family Columelliaceae, though formerly in Loganiaceae,[2] Potaliaceae (now subsumed in Gentianaceae), or a family of its own, Desfontainiaceae.

The genus was named for the French botanist, René Louiche Desfontaines.[3] It is hardy to −5 °C (23 °F), and requires winter protection in areas with significant frosts.

Species

Species in the genus include:[4][5]

- Desfontainia fulgens D.Don - Chile, Argentina (Neuquén, Río Negro)

- Desfontainia spinosa Ruiz & Pav. - from Costa Rica to Chile + Argentina

- Desfontainia splendens Humb. & Bonpl. - from S Mexico to Bolivia

The best known species, D. spinosa ('Chilean holly'), is a native of rainforests and mountain slopes in southern Central America and South America, occurring from Costa Rica in the north to certain islands of Tierra del Fuego (shared by Chile and Argentina) in the extreme South, being present also in Panama, Colombia, Venezuela, Peru, Bolivia and Ecuador.[6]

Uses include medicinal / hallucinogenic purposes, a natural dye and as an ornamental evergreen shrub. In cultivation, it will grow slowly (in 10–20 years) to some 2.5 m (8 ft 2 in) in height and width, but in the wild it can also take the form of a small tree and reach around 4 m (13 ft).

It has glossy dark green, holly-like leaves, and waxy red tubular flowers, often with yellow tips, and reaching 4 cm (1.6 in) in length. The fruit is a greenish-yellow berry circa 1.5 cm (0.59 in) in diameter and contains around 44 glistening, coffee-brown seeds. It is a calcifuge (i.e. requires a lime-free environment) and will thrive in wetter conditions in the wild than it is sometimes given credit for in the horticultural literature, occurring as it does in bogs and swamps. It is usually a terrestrial plant, but can also grow as an epiphyte.

Habitat

In the Valdivian temperate rainforest of Chile and Argentina D. spinosa is typically found growing in the understorey of forests dominated by Nothofagus (southern beech) species - particularly lenga (Nothofagus pumilio) and coihue (Nothofagus dombeyi).[7]

Epiphyte

In 2001, D. spinosa was described for the first time as having been observed growing as a (fully autotrophic) epiphyte, the host tree in question being the lahuán / alerce - the gigantic and extremely long-lived conifer Fitzroya cupressoides. The epiphyte communities of the largest substrates (Substrate (biology)) (deep soil mats some 34 m (111 ft) up in the Fitzroya crowns), featured not only Desfontainia, but also the shrub Pseudopanax laetevirens (Araliaceae) and two tree species, namely Tepualia stipularis (Myrtaceae)and Weinmannia trichosperma (Cunoniaceae). These normally terrestrial species were thriving in their epiphytic existence - even a 4 m (13 ft) tall specimen of Tepualia showed no sign of stress. Some Fitzroya crowns sported such large epiphytic trees as to give the impression of a 'double crown effect.'[8]

Seed dispersal

The sole seed-dispersal vector for both epiphytic and terrestrial populations of Desfontainia in the Fitzroya forest remnants of Chile and Argentina is the chumaihuén (Dromiciops gliroides), an edible dormouse-like marsupial 20 cm (7.9 in) in length (including tail). This little creature, part frugivore and part insectivore forms an evolutionary link from the marsupials of South America to the marsupial fauna of Australia. It is better-known by its Spanish name monito del monte (little monkey of the mountain). Largely arboreal and nocturnal, Dromiciops distributes in its faeces the seeds of many of the berry-bearing, endemic plants present in its range, including those of not one, but two shrubs hallucinogenic to humans: Desfontainia spinosa (see below) and Gaultheria insana, formerly known as Pernettya furens (Ericaceae).[9][10]

Pollinators

Desfontainia spinosa, like many red-flowered plants, is pollinated by birds, the species involved being the green-backed firecrown - Sephanoides sephaniodes - the most southerly species of hummingbird. A bumblebee species - Bombus dahlbomii is also involved. Bee species are barely receptive to red wavelengths of light i.e. greater than 600 nm, but have been found still to be able to perceive red flowers, particularly blue-ish red ones, thanks to their l-receptors. Desfontainia flowers are mostly of a true red (scarlet as opposed to deep pink) but, seen with the green-sensitive component of a bee's vision, still present enough of a contrast with green foliage to be noticeable and thus pollinatable. Furthermore, the yellow flower mouths of certain varieties of Desfontainia would be visible by bees at 590 nm. (See Bee learning and communication section 1.6 Neurobiology of colour vision). Bombus dahlbomii, a large, golden-furred species and the only one native to the South American temperate forest of southern Chile and Argentina, is now, sadly, endangered, thanks to the introduction of European Bombus terrestris.[11][12][13]

Cultivation

Desfontainia spinosa was introduced into cultivation in Europe by William Lobb in 1843. It has gained the Royal Horticultural Society's Award of Garden Merit.[14][15] It requires a sheltered, partially shaded position in acid pH soil.

Uses

Desfontainia spinosa has twice been reported with voucher specimens as a hallucinogen from Andean southern Colombia by Richard Evans Schultes : the first time in 1942 from the Paramo de Tambillo and the second from the Paramo de San Antonio in 1953. Shamans in Colombia's Sibundoy Valley make a tea of the leaves 'when they want to dream' or 'to see visions and diagnose disease'. It is not used frequently, partly because of its potency, partly because the plant itself is not cultivated and must be gathered in the wild in remote páramos.[citation needed] The Colombian name of the shrub is Borrachero de Paramo (=intoxicating plant of the mountain bog/bleak upland moor).

The Camsá shamans of the Sibundoy Valley are also expert in the use of the dangerously toxic solanaceous hallucinogens Brugmansia and Iochroma and their occasional employment of Desfontainia for similar divinatory purposes (and reticence to speak of this practice) may well indicate a plant similarly toxic and difficult to use and causing a comparably unpleasant experience and after-effects.[16]

Desfontainia spinosa var. hookeri has been reported as a narcotic utilized by the Mapuche people of Chile by Carlos Mariani Ramirez, who also likened the bitterness of the plant to that of Gentian and mentioned its use as a yellow dye.[17]

The greenish-yellow, baccate fruit of D. spinosa is reputedly even more intoxicating than the foliage of the plant and is reported occasionally to have been brewed into a potently psychoactive type of chicha (see also Saliva-fermented beverages).[18]

Names for Desfontainia in the Mapuche language add to the knowledge of its appearance and folk uses in Chile: 'Taique' means 'shiny', in reference to the plant's glossy leaves; 'Chapico' means 'chilli water', alluding to the plant's hot and bitter taste; 'Michay Blanco' means 'white kind of yellow tree', i.e. white shrub furnishing a yellow dye' ('Michay' can also designate several species of Berberis which not only yield yellow dyes but also have bright yellow wood and also somewhat resemble Desfontainia in appearance); 'Latuy' is also a name for Latua pubiflora, the single species of the monotypic genus Latua (Solanaceae) endemic to central Chile and used by the Machi of the Mapuche people as a hallucinogen and poison to cause insanity (sometimes permanent) in a victim - which accords well with its Brugmansia-like content of tropane alkaloids.[19]

A test for alkaloids with Dragendorff's reagent (see Johann Georg Noel Dragendorff) on samples of Desfontainia from herbarium specimens collected in Argentina, Chile and Ecuador did not, however, indicate the presence of alkaloids, tropane or otherwise;[20] and, while the chemistry of Desfontainia is becoming better known, none of the compounds isolated from it thus far can account for the plant's purported hallucinogenic effects.[21]

Chemistry

Chemotaxonomically, Desfontainia has been historically placed in the family Loganiaceae,[22][23] but it is currently assigned to Columelliaceae.

Desfontainia spinosa has been found to contain, among other compounds[24] including the cucurbitacins spinoside A and B.[25] These bitter steroids, while not hallucinogenic, could contribute to the relative toxicity of the plant for human subjects, given that cucurbitacins exhibit cytotoxicity and that certain kinds have been held responsible for cases of poisoning, some fatal, by dangerously irritant/cathartic plants in the plant family Cucurbitaceae such as Ecballium elaterium and Citrullus colocynthis.

One chemical constituent of Desfontainia present in considerable quantity is the pentacyclic triterpene acid ursolic acid.

Also present are loganin and secoxyloganin, compounds related to secologanin a molecule involved in the mevalonate pathway leading to, inter alia, terpenoid and steroid biosynthesis.

Liriodendrin a ligan diglucoside also found in Liriodendron tulipifera (Magnoliaceae) and Acanthopanax senticosus (Araliaceae).[26][non-primary source needed] Liriodendrin is transformed in vivo to syringaresinol which also occurs in Castela emoryi, Prunus mume and Magnolia thailandica.

References

- ^ 1854 illustration from William Jackson Hooker (1785-1865) - Curtis's botanical magazine vol. 80 ser. 3 nr. 10 tabl. 4781 (http://www.botanicus.org/page/467611)

- ^ Leeuwenberg, A.J.M. (1969). "Notes on American Loganiaceae IV. Revision of Desfontainia". Ruiz et Pav. Acta Bot. Neerl. 18: 669–679. doi:10.1111/j.1438-8677.1969.tb00090.x.

- ^ "Desfontainia spinosa 'Harold Comber'". The Royal Horticultural Society. Archived from the original on May 11, 2008. Retrieved March 6, 2008.

- ^ The Plant List, search for Desfontainia

- ^ Tropicos, search for Desfontainia=

- ^ RHS A-Z encyclopedia of garden plants. London: Dorling Kindersley. 2008. p. 1136. ISBN 978-1-4053-3296-5.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2013-07-12. Retrieved 2013-07-24.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Clement, Joel P.; Mark W. Moffett; David C. Shaw; Antonio Lara; Diego Alarçon & Oscar L. Larrain (2001). "Crown Structure and Biodiversity in Fltzroya Cupressoides, the Giant Conifers of Alerce Andino National Park, Chile". Selbyana. 22 (1): 76–88. JSTOR 41760083.

- ^ Amico, Guillermo C.; Rodríguez-Cabal, Mariano A.; Aizen, Marcelo A. (2009). "The potential key seed-dispersing role of the arboreal marsupial Dromiciops gliroides". Acta Oecologica. 35 (1): 8–13. Bibcode:2009AcO....35....8A. doi:10.1016/j.actao.2008.07.003.

- ^ Myers, P.; Espinosa, R.; Parr, C.S.; Jones T.; Hammond, G.S. & Dewey T.A. (2013). "The Animal Diversity Web".

- ^ "St Andrews Botanical Garden Plant of the Month". August 2002.

- ^ Martinez-Harms, J.; Palacios, A. G.; Marquez, N.; Estay, P.; Arroyo, M. T. K.; Mpodozis, J. (2010). "Can red flowers be conspicuous to bees? Bombus dahlbomii and South American temperate forest flowers as a case in point". Journal of Experimental Biology. 213 (4): 564–71. doi:10.1242/jeb.037622. PMID 20118307.

- ^ Goulson, D. Argentinian Invasion! Buzzword 21 pp.17-18 [full citation needed]

- ^ "Desfontainia spinosa AGM". Royal Horticultural Society. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- ^ "AGM Plants - Ornamental" (PDF). Royal Horticultural Society. July 2017. p. 29. Retrieved 6 February 2018.

- ^ Schultes, Richard Evans; Hofmann, Albert (1979). The Botany and Chemistry of Hallucinogens (2nd ed.). Springfield Illinois: Charles C. Thomas.[page needed]

- ^ Bello, Andrés, ed. (1965). Témas de Hipnosis pps. 262-263. Santiago, Chile.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Rätsch, Christian (1998). The Encyclopedia of Psychoactive Plants: Ethnopharmacology and its Applications. Rochester: Park Street Press.[page needed]

- ^ Plowman, T.; Gyllenhaal, L.O. & Lindgren J.E. (1971). "Latua pubiflora, magic plant from southern Chile". Botanical Museum Leaflets. 23: 61–92.

- ^ Schultes, Richard Evans.1977.De Plantis Toxicariis e Mundo Novo Tropicale Commentationes XV: Desfontainia a new Andean hallucinogen.Botanical Museum Leaflets 25 (3):99-104.

- ^ Schultes, R.E. De speciebus varietatibusque Desfontainia - colombianae notae. Rev. Acad. Colomb. Cienc. 17 (65): 313-319,1989. ISSN 0370-3908.

- ^ Hegnauer, R., Chemotaxonomie der Pflanzen 4 1966 p.414

- ^ Gibbs, R.D., Chemotaxonomy of Flowering Plants 3 (1974) p.1332

- ^ Houghton, Peter J.; Lian, Lu Ming (1986). "Iridoids, iridoid-triterpenoid congeners and lignans from Desfontainia spinosa". Phytochemistry. 25 (8): 1907–12. doi:10.1016/S0031-9422(00)81172-3.

- ^ Houghton, Peter J.; Lian, Lu Ming (1986). "Triterpenoids from Desfontainia spinosa". Phytochemistry. 25 (8): 1939–44. doi:10.1016/S0031-9422(00)81179-6.

- ^ Jung, Hyun-Ju; Park, Hee-Juhn; Kim, Ryung-Gue; Shin, Kyoung-Min; Ha, Joohun; Choi, Jong-Won; Kim, Hyoung Ja; Lee, Yong Sup; Lee, Kyung-Tae (2003). "In vivo Anti-Inflammatory and Antinociceptive Effects of Liriodendrin Isolated from the Stem Bark of Acanthopanax senticosus". Planta Medica. 69 (7): 610–6. doi:10.1055/s-2003-41127. PMID 12898415.

External links

- [1][full citation needed]

- Entheology.org: Desfontainia spinosa

- Desfontania Spinosa at Erowid

- Every, J.L.R.(2009). Neotropical Desfontainiaceae. In:Millikan, W., Klitgård, B. & Baracat, A.(2009 onwards), Neotropikey - Interactive key and information resources for flowering plants of the Neotropics [2]