False catshark

| False catshark | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Chondrichthyes |

| Subclass: | Elasmobranchii |

| Order: | Carcharhiniformes |

| Family: | Pseudotriakidae |

| Genus: | Pseudotriakis Brito Capelo, 1868 |

| Species: | P. microdon

|

| Binomial name | |

| Pseudotriakis microdon Brito Capelo, 1868

| |

| |

| Range of the false catshark[1] | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Pseudotriakis acrales Jordan & Snyder, 1904 | |

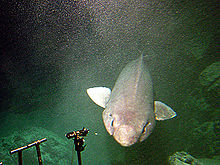

The false catshark or sofa shark (Pseudotriakis microdon) is a species of ground shark in the family Pseudotriakidae, and the sole member of its genus. It has a worldwide distribution, and has most commonly been recorded close to the bottom over continental and insular slopes, at depths of 500–1,400 m (1,600–4,600 ft). Reaching 3.0 m (9.8 ft) in length, this heavy-bodied shark can be readily identified by its elongated, keel-like first dorsal fin. It has long, narrow eyes and a large mouth filled with numerous tiny teeth. It is usually dark brown in color, though a few are light gray.

With flabby muscles and a large oily liver, the false catshark is a slow-moving predator and scavenger of a variety of fishes and invertebrates. It has a viviparous mode of reproduction, featuring an unusual form of oophagy in which the developing embryos consume ova or egg fragments released by the mother and use the yolk material to replenish their external yolk sacs for later use. This species typically gives birth to two pups at a time. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has assessed the conservation status of the false catshark as Least-concern. While neither targeted by fisheries nor commercially valuable, it is caught incidentally by longlines and bottom trawls, and its low reproductive rate may render it susceptible to population depletion.

Taxonomy and phylogeny

The false catshark was first described by Portuguese ichthyologist Félix de Brito Capelo in the Jornal do Sciências Mathemáticas, Physicas e Naturaes in 1868. He based his account on a 2.3 m (7.5 ft) long adult male caught off Setubal, Portugal.[2] Brito Capelo thought the specimen resembled a member of the genus Triakis, except lacking a nictitating membrane (though it is now known that this species does in fact have this trait). Thus, he assigned it to the new genus Pseudotriakis, from the Greek pseudo ("false"). At the time, Triakis was classified with the catsharks, hence "false catshark". The specific name microdon comes from the Greek mikros ("small") and odontos ("tooth").[3] Other common names for this species are dumb shark (from its Japanese name oshizame) and keel-dorsal shark.[1][4]

Pacific populations of the false catshark were once regarded as a separate species, P. acrales. However, morphological comparisons have failed to find any consistent differences between P. microdon and P. acrales, leading to the conclusion that there is only one species of false catshark.[5][6] The closest relatives of the false catshark are the gollumsharks (Gollum). Pseudotriakis and Gollum share a number of morphological similarities.[7] Phylogenetic analysis using protein-coding genes has found that the amount of genetic divergence between these taxa is less than that between some other shark species within the same genus. This result suggests that the many autapomorphies (unique traits) of the false catshark evolved relatively recently, and supports the grouping of Pseudotriakis and Gollum together in the family Pseudotriakidae.[8]

Description

Bulky and soft-bodied, the false catshark has a broad head with a short, rounded snout. The nostrils have large flaps of skin on their anterior rims. The narrow eyes are over twice as long as high, and are equipped with rudimentary nictitating membranes; behind the eyes are large spiracles. The huge mouth is arched and bears short furrows at the corners. There are over two hundred rows of tiny teeth in each jaw, arranged in straight lines in the upper jaw and diagonal lines in the lower jaw; each tooth has a pointed central cusp flanked by one or two smaller cusplets on either side. The five pairs of gill slits are fairly small.[3][5][9]

The pectoral fins are small and rounded, with fin rays only near the base. The first dorsal fin is highly distinctive, being very long (roughly equal to the caudal fin) and low, resembling the keel of a ship; it originates over the pectoral fin rear tips and terminates over the pelvic fin origins. The second dorsal fin is larger than, and originates ahead of, the anal fin; both these fins are positioned very close to the caudal fin. The caudal fin has a long upper lobe with a ventral notch near the tip, and an indistinct lower lobe.[5][9] The dermal denticles are shaped like arrowheads with a central ridge, and are sparsely distributed on the skin. This species is typically plain dark brown in color, darkening at the fin margins. However, a few individuals are instead light gray with irregular darker mottling made from fine dots. The false catshark grows up to 3.0 m (9.8 ft) long and 125 kg (276 lb) in weight.[3]

Distribution and habitat

Though rarely encountered, the false catshark has been caught from locations scattered around the world, indicating a wide circumglobal distribution. In the western Atlantic, it has been reported from Canada, the United States, Cuba, and Brazil. In the eastern Atlantic, it is known from the waters of Iceland, France, Portugal, and Senegal, as well as the islands of Madeira, the Azores, the Canaries, and Cape Verde. Records from the Indian Ocean have come from off Madagascar, the Aldabra Group, Mauritius, Indonesia, and Australia. In the Pacific Ocean, it has been documented from Japan, Taiwan, Indonesia, the Coral Sea, New Zealand, and the Hawaiian Islands.[3][10][11]

Inhabiting continental and insular slopes, the false catshark mostly occurs between the depths of 500 and 1,400 m (1,600 and 4,600 ft), though it has been recorded as deep as 1,900 m (6,200 ft). Individuals occasionally wander into relatively shallower waters over the continental shelf, perhaps following submarine canyons or suffering from an abnormal condition. The false catshark generally swims close to the sea floor and has been found at seamounts, troughs, and deepwater reefs.[1][3][5]

Biology and ecology

The soft fins, skin, and musculature of the false catshark suggest a sluggish lifestyle. An enormous oil-filled liver makes up 18–25% of its total weight, allowing it to maintain near-neutral buoyancy and hover off the bottom with little effort.[5][9] This species likely captures prey via quick bursts of speed, with its large mouth allowing it to consume food of considerable size.[5][6] It feeds mainly on bony fishes such as cutthroat eels, grenadiers, and snake mackerel, and also takes lanternsharks, squids, octopodes, and Heterocarpus shrimp.[1][6] It likely also scavenges, as examination of stomach contents have found surface-dwelling fishes such as frigate mackerel, needlefishes, and pufferfishes. One specimen caught off the Canary Islands had swallowed human garbage, including potatoes, a pear, a plastic bag, and a soft drink can.[6] There is a record of a false catshark found with bite marks from a great white shark (Carcharodon carcharias).[12]

Unusual among the ground sharks, the false catshark is viviparous with the developing embryos practicing intrauterine oophagy. Adult females have a single functional ovary, on the right, and two functional uteruses.[13] A female 2.4 m (7.9 ft) long was found to contain an estimated 20,000 ova in her ovary, averaging 9 mm (0.35 in) across. During gestation, the developing embryos are initially nourished by yolk, and later transition to feeding on ova or egg fragments ovulated by the mother. Excess egg material ingested by the embryo is stored within its external yolk sac; when close to birth, the embryo then transfers the yolk from the external yolk sac into an internal yolk sac to serve as a post-birth food reserve.[13] The typical litter size is two pups, one per uterus, though litters of four may be possible.[5] The gestation period is probably longer than one year, possibly lasting two or three years. Newborns measure 1.2–1.5 m (3.9–4.9 ft) long.[1] Males and females probably mature sexually at around 2.0–2.6 m (6.6–8.5 ft) and 2.1–2.5 m (6.9–8.2 ft) long respectively.[3][5]

Human interactions

The false catshark is an infrequent bycatch of longlines and bottom trawls. It has minimal economic value, though its meat, fins, and liver oil may be utilized.[1][10] In Okinawa, its oil is traditionally used to seal the hulls of wooden fishing boats.[9] Like other deepwater sharks, this species is thought to be highly susceptible to overfishing due to its slow reproductive rate. However, it is rarely caught and there is no information available on its population. Therefore, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has listed it as Least Concern.[1] In June 2018 the New Zealand Department of Conservation classified the false catshark as "Data Deficient" with the qualifier "Secure Overseas" under the New Zealand Threat Classification System.[14]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h Kyne, P.M.; Yano, K. & White, W.T. (2004). "Pseudotriakis microdon". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2004.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ de Brito Capelo, F. (1868). "Descripção de dois peixes novos provenientes dos mares de Portugal". Jornal do Sciências Mathemáticas, Physicas e Naturaes. 1 (4): 314–317.

- ^ a b c d e f Castro, J.H. (2011). The Sharks of North America. Oxford University Press. pp. 352–356. ISBN 978-0-19-539294-4.

- ^ Tinker, S.W. (1978). Fishes of Hawaii: A Handbook of the Marine Fishes of Hawaii and the Central Pacific Ocean. Hawaiian Service. p. 17. ISBN 978-0930492021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Compagno, L.J.V. (1984). Sharks of the World: An Annotated and Illustrated Catalogue of Shark Species Known to Date. Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations. pp. 378–379. ISBN 978-92-5-101384-7.

- ^ a b c d Yano, K.; Musick, J.A. (1992). "Comparison of morphometrics of Atlantic and Pacific specimens of the false catshark, Pseudotriakis microdon, with notes on stomach contents". Copeia. 1992 (3): 877–886. doi:10.2307/1446165. JSTOR 1446165.

- ^ Compagno, L.J.V. (1988). Sharks of the order Carcharhiniformes. Princeton University Press. pp. 192–194. ISBN 978-0-691-08453-4.

- ^ López, J.A.; Ryburn, J.A.; Fedrigo, O.; Naylor, G.J.P. (2006). "Phylogeny of sharks of the family Triakidae (Carcharhiniformes) and its implications for the evolution of carcharhiniform placental viviparity". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 40 (1): 50–60. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2006.02.011. PMID 16564708.

- ^ a b c d Last, PR; Stevens, JD (2009). Sharks and Rays of Australia (second ed.). Harvard University Press. pp. 32–33. ISBN 978-0-674-03411-2.

- ^ a b Froese, R.; Pauly, D. (eds). (2011). "Pseudotriakis microdon". FishBase. Retrieved on April 18, 2013.

- ^ Lee, JJ (August 15, 2013). "Ghost, Demon, and Cat Sharks Found". Weird & Wild. National Geographic. Archived from the original on August 28, 2013. Retrieved September 5, 2013.

- ^ Tirard, P.; Manning, M.J.; Jollit, I.; Duffy, C.; Borsa, P. (2010). "Records of Great White Sharks (Carcharodon carcharias) in New Caledonian Waters". Pacific Science. 64 (4): 567–576. doi:10.2984/64.4.567. hdl:10125/23127.

- ^ a b Yano, K. (1992). "Comments on the reproductive mode of the false cat shark Pseudotriakis microdon". Copeia. 1992 (2): 460–468. doi:10.2307/1446205. JSTOR 1446205.

- ^ Duffy, Clinton A. J.; Francis, Malcolm; Dunn, M. R.; Finucci, Brit; Ford, Richard; Hitchmough, Rod; Rolfe, Jeremy (2018). Conservation status of New Zealand chondrichthyans (chimaeras, sharks and rays), 2016 (PDF). Wellington, New Zealand: Department of Conservation. p. 11. ISBN 9781988514628. OCLC 1042901090.