Cholesbury Camp

| Cholesbury Camp | |

|---|---|

Interior of Cholesbury Camp | |

| General information | |

| Architectural style | Iron Age hill fort |

| Town or city | Cholesbury |

| Country | England |

| Coordinates | 51°45′22″N 0°39′14″W / 51.756062°N 0.653957°W |

| Construction started | 2nd century BC? |

| Technical details | |

| Size | 15 acres (6.1 ha) |

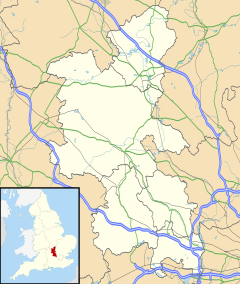

Cholesbury Camp is a large and well-preserved Iron Age hill fort on the northern edge of the village of Cholesbury in Buckinghamshire, England. It is roughly oval-shaped and covers an area, including ramparts, of 15 acres (6.1 ha),[1] and measures approximately 310 m (1,020 ft) north-east to south-west by 230 m (750 ft) north-west to south-east. The interior is a fairly level plateau which has been in agricultural use since the medieval period.[2] The hill fort is now a scheduled ancient monument.[1]

The fort is of the multivallate type, in other words having two or more lines of concentric earthworks. Most examples of such forts were built and used during the British Iron Age period between the 6th century BC and the Roman invasion of Britain in the 1st century AD.[2] The period of Cholesbury Camp's construction is unclear, but it has been suggested that it may lie between the 2nd and 1st centuries BC, during the middle to late iron age.[1][3] It was previously, though erroneously, attributed to the Danes and until the early 20th century was known locally as "The Danish Camp" and incorrectly recorded as such on maps.[2] It has also been suggested that it may have been constructed on the same site as an earlier, Bronze Age defensive structure.[4]

The fort is located in the Chiltern Hills at an altitude of over 190 m (620 ft). The porosity of the ground in the area severely limited the availability of surface water, essential for livestock, and therefore precluded year-round settlement adjacent to most of the upland pastures. However, there are two aquifer-fed water sources: Holy (or Holly) and Bury Ponds. The constancy of this supply, over many hundreds of years, is cited as being crucial to the decision as to where to site the hill fort and for the early establishment of the isolated community at Cholesbury.[5]

Structure and layout

The earthen ramparts of the sub-oval shaped fort are today largely overgrown with a double belt of mature beech trees, planted in the early 19th century. Inside the ramparts the enclosed area is a level plateau 10 acres (4.0 ha) in area, treeless and given over to grazing. There are four entrances to the central enclosure, though only one is thought to be original.[2] Most of the ramparts still remain well-preserved, though along a 230 metres (750 ft) section of the southern side the ramparts are missing. The absence of earthworks in this section today is believed to be due to the demolition of ramparts to make way for buildings constructed between the 16th and early 19th centuries, together with associated livestock enclosures and allotments. However, there has also been speculation that the earthworks were always much more modest along this section, providing ample opportunity to exploit as sites for domestic habitation. As properties were built and later enlarged or replaced with more substantial buildings, and their associated allotments became gardens and orchards, the residue of the original ramparts were all but rubbed out and any remaining ditches almost completely infilled. The ramparts on the south-east and south-west quadrants consist principally of two sets of banks (inner and outer) each enclosing a large ditch. On the north-east and north-west quadrant there is a single ditch bounded on each side by a bank.[6]

The inner bank is on average 8 metres (26 ft) wide with a height that varies between 0.8 metres (2.6 ft) to 2 metres (6.6 ft). Its front slope is angled at about 35 degrees and the rear slope at 50 degrees. The broad, flat top of the bank does not appear to have been lined with timber or stonework.[6] The adjoining inner ditch ranges from 6 metres (20 ft) to 12 metres (39 ft) wide and 2.5 metres (8.2 ft) to 3 metres (9.8 ft) deep, in the shape of a steep-sided V with an inner slope of about 50 degrees. The outer bank is less distinct but is still visible on the northern side of the fort. The banks and ditches to the south-east are particularly well-preserved extending the ramparts for a distance of about 90 metres (300 ft).[1][7]

The outer ditch and banks of the north-west quadrant do not follow the curvature of the inner rampart over its whole length. The final 53 metres (174 ft) of the ditch runs almost straight out in a north-north-easterly direction. The triangular section so created is bounded on its northern edge by a shallow ditch and bank.[6]

History of the fort

Period of occupation

Excavations by Day Kimball in 1932 indicated that during the Iron Age, Cholesbury Camp was only sparsely, and possibly intermittently inhabited, presumably in times of strife when it provided a refuge or a defensive position.[6]

Well-preserved remains of prehistoric hearths or fire-sites and the remains of a clay-lined oven were found. Three of the hearths appear to have been used to smelt iron, also evidenced by finds of bloomery slag.[1] Only a few poor quality pottery shards were found from the Middle Iron Age period, in contrast to numerous fragments of Belgic pottery from the Late Iron Age (approximately 200BC-50AD). Lastly, some rare examples of quern-stone fragments imported from the Eifel region of present-day Germany suggested it might have been a high status encampment.[2]

The main period of occupation appears to have been around the middle of the 1st century BC.[1] Kimball also speculated from analysis of a series of trenches dug in the 'triangle' of ramparts in the north-western quadrant, that there were remnants of an earlier earthwork structure (single bank and ditch) extending as an arc in a northerly direction away from the hill fort. Kimball concluded that the absence of Romano-British pottery shards strongly indicated the hill fort was generally deserted from the time of the Roman occupation of Britain in 54AD until the early medieval period.[6]

In 1953 there was an accidental find within the Camp of a gold quarter stater, minted on the continent in the Gallo-Belgic region, between the mid-second and mid-first century BC. Its discovery provided further corroboration for the likely period of occupation postulated by Kimball.[8] Such occurrences can be the result of trade activity, or a gift to a high-ranking individual, or even intentional deposition as a sacred offering to the gods.[9]

Post-Roman

Following the period of Roman administration, as land was cleared for use as summer pasture, a small settlement gradually developed, associated with nearby Drayton Beauchamp. More permanent occupation in and around the previously deserted hill fort began during the later Anglo-Saxon period leading to an expansion into a nucleated village from which the present-day village of Cholesbury eventually developed. The first record of the settlement's name, as Chelwoldesbyr, was at the end of the 13th century. The name derives from the Anglo-Saxon Ceolweald's burh (i.e. the fortified place of Ceolweald's people).[10]

Mediaeval period

A small amount of mediaeval pottery shards were found by Kimball in 1932 which he concluded were not related to reoccupation, but rather the result of the manuring of the fields during the early stages of the establishment of the settlement outside the Camp.[6] However, a geophysical survey carried out in the interior of the fort in 2000 found possible evidence that the interior may have been reoccupied in the mediaeval period. The results suggested a possible site of an early manor house associated with the church which dates from the around the 12th century.[11] Subsequently, Cholesbury Manor House was constructed in the 16th century located on the southern range of the ramparts of the hill fort.[12]

Church of St Lawrence

Today the Church of St Lawrence is located within the remains of the defences of the Iron Age fort, one of two such churches of the same name built within a hill fort in Buckinghamshire. Its location suggests that the fort still had some kind of politico-religious significance long after its original use had been forgotten.[13] The oldest parts of the present church were built in the Early English Style, dating the original stone-built church to the 12–13th century, which possibly replaced an earlier Anglo-Saxon wooden church. After falling into disrepair the church was partly rebuilt and restored in the 1870s in the Victorian style.[14]

References

- ^ a b c d e f Cholesbury Camp Archived 2012-10-01 at the Wayback Machine. Pastscape, English Heritage. Accessed 20 February 2011

- ^ a b c d e "Cholesbury Camp", information board at location. Chiltern Conservation Board, date unknown.

- ^ Richard Cavendish, Prehistoric England, p. 92. British Heritage Press, 1983. ISBN 978-0-517-41728-7

- ^ Branigan, Keith. (1967). "The distribution and development of Romano-British occupation in the Chess Valley". Records of Buckinghamshire. 18: 136–49.

- ^ Hepple & Doggett, Leslie & Alison (1971). The Chilterns. England: Phillimore & Co Ltd. ISBN 978-0-85033-833-1.

- ^ a b c d e f Kimble G. D.(1933) Cholesbury Camp J. Brit. Arch. Assn. Vol 39(1) 187-212

- ^ Michael Avery, Hillfort Defences of Southern Britain. Volume II, Appendix A, p. 105. Tempus Reparatum, 1993. ISBN 978-0-86054-754-9

- ^ Late Iron Age metalwork found on ground surface Bucks County Council Archived 2015-06-26 at the Wayback Machine, Accessed 25 June 2015

- ^ Gold Stater ('Gallo-Belgic A' type)British Museum Archived 2015-10-18 at the Wayback Machine, Accessed 25 June 2015

- ^ Ekwall, Eilert (1977). The Concise Oxford Dictionary of English Place Names. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-869103-7.

- ^ Gover, J (2001). A Geophysical Survey of Cholesbury Camp Report (unpublished).

- ^ Cholesbury Camp Archived 2011-10-14 at the Wayback Machine. Buckinghamshire County Council. Accessed 20 February 2011

- ^ Michael Reed, The landscape of Britain: from the beginnings to 1914, p. 174. Routledge, 1997. ISBN 978-0-415-15745-2

- ^ Cholesbury Parish British History Online Archived 2011-06-29 at the Wayback Machine, Retrieved 21-02-2011