Barnes Foundation

The Barnes Foundation building on Franklin Parkway in Philadelphia, 2012 | |

| Established | 1922 |

|---|---|

| Location | 2025 Benjamin Franklin Parkway Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States |

| Coordinates | 39°57′38″N 75°10′22″W / 39.9605°N 75.1727°W |

| Type | Art Museum, Horticulture |

| Key holdings | Toward Mont Sainte-Victoire (Cézanne), Portrait of the Postman Joseph Roulin (Van Gogh), Le Bonheur de Vivre (Matisse) |

| Collections | Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, Early Modern |

| Visitors | 240,000 (2015)[1] |

| Director | Thomas Collins[2] |

| Public transit access | |

| Website | barnesfoundation.org |

The Barnes Foundation is an art collection and educational institution promoting the appreciation of art and horticulture. Originally in Merion, the art collection moved in 2012 to a new building on Benjamin Franklin Parkway in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The arboretum of the Barnes Foundation remains in Merion, where it has been proposed to be maintained under a long-term educational affiliation agreement with Saint Joseph's University.[3]

The Barnes was founded in 1922 by Albert C. Barnes, who made his fortune by co-developing Argyrol, an antiseptic silver compound that was used to combat gonorrhea and inflammations of the eye, ear, nose, and throat. He sold his business, the A.C. Barnes Company, just months before the stock market crash of 1929.

Today, the foundation owns more than 4,000 objects, including over 900 paintings, estimated to be worth about $25 billion.[4] These are primarily works by Impressionist, Post-Impressionist, and Modernist masters, but the collection also includes many other paintings by leading European and American artists, as well as African art, antiquities from China, Egypt, and Greece, and Native American art.[5]

In the 1990s, the Foundation's declining finances led its leaders to various controversial moves, including sending artworks on a world tour and proposing to move the collection to Philadelphia. After numerous court challenges, the new Barnes building opened on Benjamin Franklin Parkway on May 19, 2012.[6] The foundation's current president and executive director, Thomas “Thom” Collins, was appointed on January 7, 2015.

History

Albert C. Barnes

Albert C. Barnes began collecting art as early as 1902, but became a serious collector in 1912. He was assisted at first by painter William Glackens, an old schoolmate from Central High School in Philadelphia. On an art buying trip to Paris, France, Barnes visited the home of Gertrude and Leo Stein where he purchased his first two paintings by Henri Matisse.[7] In the 1920s, Barnes became acquainted with the work of other modern artists such as Pablo Picasso, Amedeo Modigliani and Giorgio de Chirico through his Paris art dealer Paul Guillaume.

On December 4, 1922, Barnes received a charter from the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania establishing the Barnes Foundation as an educational institution dedicated to promoting the appreciation of fine art and arboriculture. He purchased property in Merion from the American Civil War veteran and horticulturist Captain Joseph Lapsley Wilson, who had established an arboretum there in around 1880. He commissioned architect Paul Philippe Cret to design a complex of buildings, including a gallery, an administration building, and a service building.[8] The Barnes Foundation officially opened on March 19, 1925.[7]

The main building features several unusual Cubist bas-reliefs commissioned by Barnes from the sculptor Jacques Lipchitz. Elements of African art decorate the exterior wrought iron and the tile work created by the Enfield Pottery and Tile Works on the front portico of the building. Barnes built his home next to the gallery, which now serves as the administration building of the Foundation. His wife, Laura Leggett Barnes, developed the Arboretum of the Barnes Foundation and its horticultural education program in 1940.[9]

Art education programs

In 1908, Barnes organized his business, the A.C. Barnes Company, as a cooperative, devoting two hours of the work day to seminars for his workers. They read philosophers William James, Georges Santayana, and John Dewey.[10] Barnes also brought some of his art collection into the laboratory for the workers to consider and discuss. This kind of direct experience with art was inspired by the education philosophy of John Dewey and planted the seed that eventually grew into the establishment of the Barnes Foundation. The two met at a Columbia University seminar in 1917 becoming close friends and collaborators spanning more than three decades.[7]

Barnes's conception of his foundation as a school rather than a typical museum was shaped through his collaboration with John Dewey (1859–1952). Like Dewey, Barnes believed that learning should be experiential.[11] The Foundation classes included experiencing original art works, participating in class discussion, reading about philosophy and the traditions of art, as well as looking objectively at the artists' use of light, line, color, and space. Barnes believed that students would not only learn about art from these experiences but that they would also develop their own critical thinking skills enabling them to become more productive members of a democratic society.[12]

The early education programs at the Barnes Foundation were taught in partnership with the University of Pennsylvania and Columbia University. The courses at Penn were first taught by Laurence Buermeyer (1889–1970), who held a philosophy PhD from Princeton, and later by Thomas Munro (1897–1974), a philosophy professor and one of Dewey's students.[12] Each served as the Associate Director of Education, while Dewey served in the largely honorary position of Director of Education.[12]

Another collaborator was Violette de Mazia (1896–1988), who was born in Paris and educated in Belgium and England.[13] Originally hired to teach French to the Foundation staff in 1925, de Mazia became a close associate of Barnes, teaching and co-authoring four Foundation publications.[7] After Barnes' death, she became a trustee and the Director of Education of the Art Department, continuing to express Barnes' philosophy in her teaching. The Violette de Mazia Foundation was then established after her death, and in 2011 the Barnes Foundation came to an agreement with them to allow the de Mazia Foundation student access to the collection for art education after its move to the Parkway.[14] In 2015 however, the de Mazia Foundation ceased its operations and was absorbed by the Barnes Foundation.[15]

Barnes created detailed terms of operation in an indenture of trust to be honored in perpetuity after his death. These included limiting public admission to two days a week, so the school could use the art collection primarily for student study, and prohibiting the loan of works in the collection, colored reproductions of its works, touring the collection, and presenting touring exhibitions of other art.[16] Matisse is said to have hailed the school as the only sane place in America to view art.[17]

Post-Barnes era

| External audio | |

|---|---|

After a decade of legal challenges, the public was allowed regular access to the collection in 1961. Public access was expanded to two and a half days a week, with a limit of 500 visitors per week; reservations were required by telephone at least two weeks in advance.[19] Harold J. Weigand, an editor of The Philadelphia Inquirer, with the consent of, but not directly on behalf of, the Pennsylvania Attorney General, had filed an earlier suit for access but been unsuccessful.[20]

Financial crisis

In 1992, Richard H. Glanton, president of the foundation, said the museum needed extensive repairs to upgrade its mechanical systems, provide for maintenance and preservation of artworks, and improve security. The old Philadelphia firm J.S. Cornell & Son was the contractor of choice. In order to raise the money, Glanton decided to break some terms of the indenture. From 1993 to 1995, 83 of the collection's Impressionist and post-Impressionist paintings were sent on a world tour, attracting large crowds in numerous cities, including Washington, D.C.; Fort Worth, Texas; Paris; Tokyo; Toronto; and Philadelphia at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.[21][22]

The revenue earned from the tour of paintings was still not enough to ensure its endowment. By fall 1998, Glanton and fellow board member Niara Sudarkasa were suing each other. Lincoln University, which according to the Barnes Foundation's indenture, controlled four of the five seats on the board of trustees, began an investigation into the Foundation's finances. The Foundation's board believed that a similar investigation was warranted for activities during Glanton's tenure as president. In 1998 the board of directors began a forensic audit conducted by Deloitte, which was kept private for three years, eventually released, and criticized Glanton's expenses and management.[23]

In 1998, Kimberly Camp was hired as the foundation's CEO and first arts professional to run the Barnes. During her seven-year tenure, she turned the struggling foundation around and provided necessary support to the petition to move the Barnes to Philadelphia.

Proposed move

On September 24, 2002, the foundation announced that it would petition the Montgomery County Orphans' Court (which oversees its operations) to allow the art collection to be moved to Philadelphia (which offered a site on the Benjamin Franklin Parkway) and to triple the number of trustees to 15. The foundation's indenture of trust stipulates that the paintings in the collection be kept "in exactly the places they are".[22]

The foundation argued that it needed to expand the board of trustees from five (four of which were held by persons appointed by Lincoln University) to 15 to increase fundraising. For the same reason, it needed to move the gallery from Merion to a site in Center City, Philadelphia, which would provide greater public access. In its brief to the court, the foundation said that donors were reluctant to commit continuing financial resources to the Barnes unless the gallery were to become more accessible to the public.[24]

On December 15, 2004, after a two-year legal battle that included an examination of the foundation's financial situation, Judge Stanley Ott ruled that the foundation could move.[24][25] Three charitable foundations, The Pew Charitable Trusts, the Lenfest Foundation and the Annenberg Foundation, had agreed to help the Barnes raise $150 million for a new building and endowment on the condition that the move be approved.[26]

On June 13, 2005, the Foundation's president, Kimberly Camp, announced her resignation, to take effect no later than January 1, 2006. Camp had been appointed in 1998 with the goal of stabilizing and restoring the foundation to its original mission. During her tenure, she began the Collection Assessment Project, the first full-scale effort to catalog and stabilize the artworks; brought in exemplary professional staff; created the fundraising program; restored Ker-feal and the Barnes Arboretum; and worked with the board to approve policies and procedures to make the foundation viable. In 2002, Dr. Bernard C. Watson began the proposal to move the Barnes.[27]

The foundation pledged to reproduce Barnes's artistic arrangement of the artworks and other furniture within the new gallery to maintain the experience as he intended.[28]

Planning the move

In August 2006, the Barnes Foundation announced that it was beginning a planning analysis for the new gallery. The board selected Derek Gillman (formerly of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts) as the new director and president.[29] In June 2011, the foundation announced that it had surpassed its $200 million fund-raising goal, of which $150 million would go toward construction of the Philadelphia building and associated costs, and $50 million to the foundation's endowment.[30]

The foundation proceeded with plans to build a new facility in the 2000 block of the Benjamin Franklin Parkway, near the Rodin Museum and the Philadelphia Museum of Art.[31] Tod Williams & Billie Tsien Architects of New York were lead architects of the building project. The building team also consisted of the Philadelphia-based firm, Ballinger, as associate architect; OLIN as landscape architect; and Fisher Marantz Stone as lighting designers. Aegis Property Group served as external project managers, with L. F. Driscoll as construction managers. Project executive Bill McDowell supervised and coordinated the project for the foundation.[32]

Construction for the new building began in fall, 2009 and the building opened in May, 2012. The new galleries were designed to replicate the scale, proportion and configuration of the original galleries in Merion. Reviews have praised the new facility, claiming the additional natural light has improved the viewing experience. The new site contains more space for the foundation's art education program and conservation department, a retail shop, and cafe.[33]

Legal challenges to the move

After Judge Ott's decision in 2004,[25][34] The Friends of the Barnes Foundation and Montgomery County filed briefs in Montgomery County Orphan's Court to reopen the hearings that allowed the move. They hoped to persuade Ott to reopen the case because of the changed circumstances in the County. On May 15, 2008, Ott published an opinion dismissing the request of both the Friends of the Barnes Foundation and the Montgomery County Commissioners to reopen the case due to lack of standing. Congressman Jim Gerlach strongly supported keeping the Barnes in Merion.[35][36]

On May 20, 2009, Friends of the Barnes Foundation appeared before the Commissioners of the Delaware River Port Authority (DRPA) in Camden, New Jersey, to request that they reconsider their 2003 authorization of a grant of $500,000 toward the plan to move the foundation. They contended there was insufficient evidence of substantial economic benefit to Philadelphia, and that DRPA had not undertaken necessary economic evaluation assessing the impact at both locations. They introduced a study by economist Matityahu Marcus that challenged the claimed benefits.[37] The DRPA said that it would consider the Friends' request but did not change its decision.[38] The history is chronicled in the HBO documentary The Collector.[39]

In late February 2011, The Friends of the Barnes Foundation filed a petition to reopen the case. A new hearing, set for March 18, was postponed until August 3, 2011. The court ordered the foundation and the Attorney General's office, who argued in favor of the move, to explain why the case should not be reopened. The opposition group, Friends of the Barnes Foundation, says The Art of the Steal revealed that Ott did not have all the evidence in 2006, when he approved the art collection's move.[40] On October 6, 2011, Judge Ott ruled that the Friends of the Barnes Foundation had no legal standing and that there was no new information in the movie.[41][42]

After the move

After the move, the Barnes Foundation retained its ownership of the building in Merion, using it as a storage space. In 2018, Saint Joseph's University took a 30-year lease on the building and its adjoining arboretum at a cost of $100 a year, with Saint Joseph's University undertaking to pay the maintenance and security costs for the property. The lease allows the university to hang its own artworks in the gallery space.[43]

Collection

The collection includes:

- 181 paintings by Pierre-Auguste Renoir

- 69 by Paul Cézanne

- 59 by Henri Matisse

- 46 by Pablo Picasso

- 21 by Chaim Soutine

- 18 by Henri Rousseau

- 16 by Amedeo Modigliani

- 11 by Edgar Degas

- 11 by Giorgio de Chirico

- 7 by Vincent van Gogh

- 6 by Georges Seurat

Other European and American masters in the collection include Peter Paul Rubens, Titian, Paul Gauguin, El Greco, Francisco Goya, Édouard Manet, Jean Hugo, Claude Monet, Maurice Utrillo, William Glackens, Charles Demuth, Horace Pippin, Jules Pascin and Maurice Prendergast. It also holds a variety of African artworks; ancient Egyptian, Greek, and Roman art; Native American works, American and European furniture, decorative arts and metalwork. The museum also holds several significant works by cubist sculptor Jacques Lipchitz.

The collection displays different types of artworks according to Barnes' methodology in "wall ensembles", often alongside hand-wrought iron, antique furniture, jewelry and sculpture, which allow comparison and study of works from various time periods, geographic areas, and styles.[44][45]

After Barnes met Matisse in the United States, he commissioned The Dance II, a 45-by-15-foot triptych that was placed above Palladian windows in the main gallery space.[46][47]

Notable holdings

-

Gustave Courbet, Les Bas Blancs, (Woman with White Stockings) (c. 1861)

-

Claude Monet, Camille au métier (1875)

-

Claude Monet, Le Bateau-atelier (1876)

-

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Jeune garçon sur la plage d'Yport (1883)

-

Henri Toulouse-Lautrec, A Montrouge – Rosa la Rouge (1886–87)

-

Paul Cézanne, Portrait of Madame Cézanne (1885–1887)

-

Georges Seurat, Models (Les Poseuses) (1886–1888)

-

Vincent van Gogh, Nude Woman on a Bed (1887)

-

Vincent van Gogh, The Smoker (1888)

-

Vincent van Gogh, Still Life (1888)

-

Vincent van Gogh, Portrait of the Postman Joseph Roulin (1889)

-

Vincent van Gogh, Thatched Cottages in the Sunshine (1890)

-

Paul Cézanne, Pots en terre cuite et fleurs (1891–92)

-

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Noirmoutier (1892)

-

Paul Gauguin, Haere Pape (1892)

-

Paul Cézanne, The Card Players, (1890–1892)

-

Paul Cézanne, Mont Sainte-Victoire seen from Bellevue (1892–1895)

-

Paul Cézanne, Nature morte au crane (1896–1898)

-

Paul Cézanne, Portrait of a Woman (c. 1898)

-

Henri Rousseau, Scout attacked by a Tiger (1904)

-

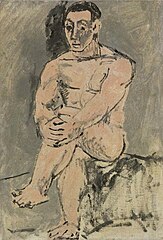

Pablo Picasso, 1906, Seated Male Nude (1906)

-

Henri Matisse, Le bonheur de vivre (1906)

-

Henri Matisse, Nature morte bleue (Blue Still Life) (1907)

-

Henri Matisse, Madras Rouge (1907)

-

Henri Matisse, Le Rifain assis (1912–13)

-

Henri Matisse, Still Life with Gourds (Nature morte aux coloquintes) (1916)

-

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Les baigneuses (1918)

-

Amedeo Modigliani, Jeanne Hébuterne (1919)

Merion Arboretum

The original Barnes Foundation campus in Merion, Pennsylvania, is now a 12-acre arboretum open to the public for tours. The plant collection features favorite plants assembled by Mrs. Barnes for teaching purposes, and includes stewartia, aesculus, phellodendron, clethra, magnolia, viburnums, lilacs, roses, peonies, hostas, medicinal plants, and hardy ferns.[48] A herbarium and horticulture library is available to the Foundation's horticulture students and other scholars by appointment. Classes are offered in horticulture topics for the general public.

Films

- Glenn Holsten: The Barnes Collection (2012)

- Jeff Folmsbee: The Collector (2010)

- Don Argott: The Art of the Steal (2009)

- Alain Jaubert: Citizen Barnes: An American Dream (1993)

See also

References

- ^ "The Barnes Foundation 2015 Annual Report" (Press release). The Barnes Foundation. Retrieved January 12, 2017.

- ^ "Thomas "Thom" Collins Named Executive Director and President of the Barnes Foundation" (Press release). Barnes Foundation. January 7, 2015. Retrieved October 4, 2017.

- ^ "SJU Announces Planned Educational Affiliation with Barnes Foundation". Saint Joseph's University News. November 3, 2017. Retrieved 7 December 2017.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Barnes $25 Billion Art Trove, Boardroom Fight Drive Documentary". Bloomberg. February 26, 2010. Retrieved March 12, 2010.

- ^ "Collection Fact Sheet” in the Philadelphia Opening Press Kit, Barnes Foundation, 2012 https://www.barnesfoundation.org/press/press-releases/move-press-kit-2012.

- ^ "Philly Home for Barnes Collection to Open May 19". September 15, 2011. Retrieved January 19, 2012.

- ^ a b c d “Biographical Note,” Presidents Files, Albert C. Barnes Correspondence. The Barnes Foundation Archives, 2012. https://www.barnesfoundation.org/whats-on/collection/library-archives/finding-aids.

- ^ "Historical Note," Directors of the Arboretum, Joseph Lapsley Wilson, The Barnes Foundation Archives, 2012. https://www.barnesfoundation.org/whats-on/collection/library-archives/finding-aids.

- ^ "Historical Note," Directors of the Arboretum, Laura Leggett Barnes, The Barnes Foundation Archives, 2012. https://www.barnesfoundation.org/whats-on/collection/library-archives/finding-aids.

- ^ Laurence Buermeyer, "An Experiment in Education", The Nation 120, 3119 (April 1925): 422–423.

- ^ John Dewey, Democracy and Education, (New York: The Free Press, 1966), 163.

- ^ a b c "Historical Note", Early Education Records, The Barnes Foundation Archives, 2012. https://www.barnesfoundation.org/whats-on/collection/library-archives/finding-aids.

- ^ Mary Ann Meyers, Art, Education, & African-American Culture: Albert Barnes and the Science of Philanthropy (New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers, 2004), 151.

- ^ "Barnes Foundation and Violette de Mazia Foundation announce joint education agreement", Mainline Media News, 16 November 2011, accessed 5 April 2013. http://www.mainlinemedianews.com/mainlinetimes/news/barnes-foundation-and-violette-de-mazia-foundation-announce-joint-education/article_61061247-7c09-58e6-95bc-5524c2ee5006.html

- ^ "Barnes, Violette de Mazia Foundations to Merge". Philanthropy News Digest. April 20, 2015.

- ^ "In Re Barnes Foundation Annotate this Case 453 Pa. Superior Ct. 436 (1996) 684 A.2d 123". Justicia US Law. September 9, 1996. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

- ^ Russell, John (1999). Matisse: Father & Son. New York City: Abrams Books. p. 61.

- ^ "How Philadelphia's Barnes Foundation Is Leveraging Analytics". podcast and transcript. Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania. May 23, 2019. Retrieved May 24, 2019.

- ^ Commonwealth v. Barnes Found., 159 A.2d 500, 506 (Pa. 1960).

- ^ Wiegand v. Barnes Foundation, 97 A.2d 81 (Pa. 1953).

- ^ Kastner, Jeffrey (December 8, 1999). "Tired of Fighting: A New Director Is Trying To Turn Around the Embattled Barnes Foundation". Dalet Art. Retrieved September 13, 2007.

- ^ a b "Judge Orders Barnes Foundation To Share Audit". FoundationCenter.org. April 30, 2003. Retrieved September 12, 2007.

- ^ Blumenthal, Ralph (July 2, 2003). "Audit Sharply Criticizes Art Institution's Dealings". The New York Times.

- ^ a b "Montgomery Court Approves Barnes Foundation Move". PhilaCulture.org. December 15, 2004. Archived from the original on August 9, 2011. Retrieved September 13, 2007.

- ^ a b In re Barnes Foundation, 25 Fiduc.Rep.2d 39, 69 Pa. D. & C.4th 129, 2004 WL 2903655 (Pa. Com. Pl. 2004).

- ^ Anderson, John (2003). Art Held Hostage: The Battle over the Barnes Collection. W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-04889-6.

- ^ [dead link] "Barnes President To Leave by January". Philly.com. Retrieved September 13, 2007.

- ^ Sozanski, Edward J. (May 4, 2003). "Relocation Makes Sense, But It Would Be Wrong". Barnes Foundation. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved September 13, 2007.

- ^ "Barnes Foundation Announces the Appointment of Derek Gillman as Its New Executive Director and President". Barnes Foundation. August 7, 2006. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved September 13, 2007.

- ^ "Barnes passes $200M mark for new home". June 28, 2011. Retrieved January 19, 2012.

- ^ Rybczynski, Witold (April 27, 2005). "Extreme Museum Makeover". Slate. Archived from the original on November 25, 2006. Retrieved September 13, 2007.

- ^ "The Barnes Foundation Announces New Building on Benjamin Franklin Parkway To Be Complete by 2011". October 16, 2008. Archived from the original on October 14, 2010. Retrieved October 20, 2009.

- ^ "The Barnes Foundation Announces a New Building on Benjamin Franklin Parkway To Be Complete by 2011" Archived 2010-10-14 at the Wayback Machine. Barnes Foundation.

- ^ In re Barnes Foundation, 24 Fiduc.Rep.2d 94, 2004 WL 1960204 (Pa. Com. Pl. 2004).

- ^ "U.S. Representative Jim Gerlach's Statement Friends of the Barnes Lawsuit" (PDF). BarnesFriends.org. Retrieved September 13, 2007.

- ^ "United Political Front Asks PA Attorney General To Reopen Barnes Case" (PDF). BarnesFriends.org. Retrieved September 13, 2007.

- ^ "$500,000 Barnes Foundation grant questioned". LA Times Blogs - Culture Monster. 2010-08-19. Retrieved 2017-07-09.

- ^ "Friends of Barnes still trying to stop move". Newsworks.org. Retrieved 2017-07-09.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "THE COLLECTOR: Dr. Albert C. Barnes". Vimeo.

- ^ AP, "Judge Sets Hearing Date in Barnes Foundation Case", reproduced at Friends of the Barnes Foundation Website

- ^ "Judge upholds Barnes Foundation's move to Philly". 6abc Philadelphia. Retrieved 2017-07-08.

- ^ "Judge Ott's Opinion and Order Dated October 6, 2011". Friends of the Barnes Foundation. Retrieved 7 February 2014.

- ^ Saint Joseph's University will run original Barnes property in Lower Merion [1]

- ^ "A quiet suburb is home to stunning Barnes Collection". tribunedigital-baltimoresun. Retrieved 2017-07-08.

- ^ "Ensembles (Part 1)". PBS LearningMedia. Retrieved 2017-07-08.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "New Barnes Building Opens, Why People are Upset". artfagcity.com. 16 May 2012.

- ^ Flam, Jack, Matisse: The Dance, National Gallery of Art, Washington, 1993.

- ^ "Merion". Barnes Foundation. Archived from the original on 5 October 2014. Retrieved 1 October 2014.

External links

- 1922 establishments in Pennsylvania

- Arboreta in Pennsylvania

- Art museums established in 1922

- Art museums in Pennsylvania

- Art museums in Philadelphia

- Art schools in Pennsylvania

- Arts foundations based in the United States

- Education in Philadelphia

- Educational institutions established in 1922

- Former private collections in the United States

- Logan Square, Philadelphia

- Lower Merion Township, Pennsylvania

- Paul Philippe Cret buildings

- Protected areas of Montgomery County, Pennsylvania

- African art museums in the United States