RMS Asturias (1925)

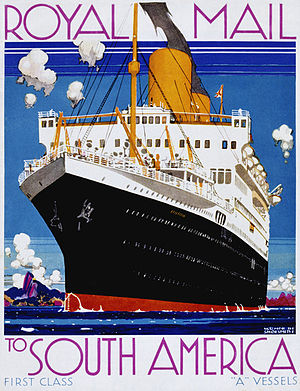

RML poster of Asturias with her funnels raised in height after she was rebuilt as a turbine steamship.

Painting by Kenneth Shoesmith. | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name |

|

| Namesake | Principality of Asturias |

| Owner |

|

| Operator | |

| Port of registry | |

| Route | Southampton – South America |

| Builder | Harland & Wolff, Belfast |

| Yard number | 507 |

| Launched | 7 July 1925 |

| Sponsored by | Rosalind Hamilton, Duchess of Abercorn |

| Completed | 6 February 1926 |

| Identification |

|

| Fate | Sold for scrap, 14 September 1957 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type |

|

| Tonnage | |

| Length | 630 ft 6 in (192.18 m) |

| Beam | 78 ft 6 in (23.93 m) |

| Draught | 44 ft 9 in (13.64 m) |

| Depth | 40 ft 6 in (12.34 m) |

| Decks | 7 |

| Installed power | As built: 3,366 NHP; 10,000 ihp, 7,500 bhp |

| Propulsion |

|

| Speed |

|

| Boats & landing craft carried | built with 30 lifeboats, later reduced to 28 |

| Sensors and processing systems |

|

| Armament |

|

| Notes | sister ship: RMS Alcantara |

RMS Asturias was a Royal Mail Lines ocean liner that was built in Belfast in 1925. She served in the Second World War as an armed merchant cruiser until she was crippled by a torpedo in 1943. She was out of action until 1948 when she returned to civilian service as an emigrant ship. She became a troop ship in 1954 and was scrapped in 1957.

Background

In the First World War the Royal Mail Steam Packet Company lost a number of ships to enemy action, including three of its "A-series" passenger liners: Alcantara, Aragon and Asturias.[3] After the 1918 Armistice RMSP prioritised the replacement of lost cargo ships,[4] using new refrigerated cargo ships to take a share of the growing trade in frozen meat from South America to the UK.[5]

High demand for new merchant ships to replace First World War losses kept shipbuilding prices high, so RMSP Chairman Lord Kylsant deferred ordering any new passenger liners for a few years. However, in 1921 Parliament passed the first of five Trade Facilities Acts, which offered low-interest loans and Government guarantees for repayment. In 1924 Kylsant took advantage of the Act by ordering from Harland and Wolff of Belfast a pair of 22,200 GRT passenger liners[6] with a speed of 18 to 19 knots (33 to 35 km/h).[7]

Motor ships

Harland and Wolff launched Asturias on 7 July 1925 and completed her in February 1926.[8] Her sister ship Alcantara was launched on 23 September 1926 and completed in February 1927.[9][10]

Asturias was named after Royal Mail Lines' previous Asturias, which had been a hospital ship in the First World War, survived being torpedoed in 1917 and then after returning to RMSP service after the war had been converted into the cruise ship Arcadian. The new Asturias was given the UK official number 148146 and code letters KTPJ.[11] When four-letter maritime call signs were introduced in 1934, Asturias was given the call sign GLQS.[12]

Each of the two new ships was powered by a pair of eight-cylinder four-stroke double-acting diesel engines built by Harland and Wolff to a Burmeister & Wain design. The engines gave each ship 10,000 ihp or 7,500 bhp, and at the time they were the World's largest motor ships.[10] However, their cruising speed was only 16+1⁄2 knots (30.6 km/h), which was less than that of competing ships already on the route between European ports and the South American east coast. This was an embarrassment for Lord Kylsant, who in 1924 had become Chairman of Harland and Wolff in addition to his position as chairman of RMSP.[13]

Compagnie de navigation Sud-Atlantique had two 15,000 GRT liners on the route, Lutetia (1913) and Massilia (1920), that were smaller and older but at 20 knots (37 km/h)[14] could offer a passage that was quicker by several days. Hamburg Südamerikanische Dampfschifffahrts-Gesellschaft ("Hamburg South America Steamship Company") also competed on the route with its 20,517 GRT, 19-knot (35 km/h) Cap Polonio.[15] In 1927 Hamburg Süd strengthened its competition by introducing the liner Cap Arcona, which not only matched the speed of the French ships[16] but at 27,561 GRT also became the largest ship on the route between Europe and South America.[17]

Steam turbine ships

In 1931 the Royal Mail Case resulted in the jailing of Lord Kylsant, and in 1932 the company was reconstituted as a new body, Royal Mail Lines, chaired by Lord Essendon. He claimed that German, Italian and French competitors were running ships to South America at 22 knots (41 km/h), giving a passage about five days quicker than RMSP.[15] The new RML company immediately considered how to raise the speed of Asturias and Alcantara.[13] Essendon concluded that foreign competitors were losing money at 22 knots, but a range of options to raise the speed of Asturias and Alcantara to 19 to 22 knots (35 to 41 km/h) should be evaluated. Essendon also proposed inviting foreign competitors to agree on a 19-knot speed limit on the South American route, so that all companies could economise on fuel and attempt to cover their costs.[18]

At that time marine diesel power was at a relatively early stage of development, and RML considered it unable to increase the two ships' speed to the required level. Lord Essendon therefore recommended steam turbines, and two options for the drive system: either conventional reduction gearing, or the newer turbo-electric transmission that had been pioneered in the USA and successfully applied to US, UK and French ocean liners. Whichever transmission was chosen, the cost of re-engining Asturias and Alcantara was estimated at about £500,000. Lord Essendon also urged RML directors to order a third ship of similar speed to share the route with Asturias and Alcantara.[18]

Given the Great Depression at the time, the RML board rejected the idea of a new ship. At first it was prepared to have only one ship re-engined, and proposed reassigning the other to cruising to replace the ageing A-series liner Atlantis. However, in May 1933 the board consented to have both Asturias and Alcantara re-engined, and at the same time to lengthen their bows by 10 feet (3 m) and improve some of the accommodation. RML awarded the work to Harland and Wolff, but with a condition in the contract that the ships must achieve at least 18+3⁄4 knots (34.7 km/h), and a graduated penalty clause in case the actual speed increase should fall short of that figure.[19] In the same year, Lord Essendon succeeded in getting RML's competitors to accept a 19-knot speed limit on the South American route.[15]

Harland and Wolff fitted each ship with three water tube boilers supplying superheated steam at 435 lbf/in2 to a set of six turbines that drove her twin propeller shafts by single reduction gearing. The National Physical Laboratory helped the shipyard to design new aerofoil-section manganese bronze three-bladed propellers, and the rudders were also streamlined.[19] The new machinery succeeded in increasing each ship's nominal horsepower by 25% and increased their speed to about 19 knots (35 km/h).

Each ships had two funnels, of which the forward one was a dummy.[13] As built the funnels were low, which was a fashion for some 1920s and '30s motor ships. When the ships were re-engined in 1934 each funnel was increased in height.

The improvement to passenger accommodation was on "C" deck. A large number of small cabins was replaced with a smaller number of more spacious ones. As revised, "C" deck on each ship had 61 cabins, 47 of which were given en suite bathrooms.[19]

Asturias was converted first, going to Belfast in May 1934 and returning to service in October. Only after Asturias had successfully completed a voyage from Southampton to Rio de Janeiro and back did RMS send Alcantara to Harland and Wolff at Belfast in November. She returned to service in May 1935.[20]

Second World War service

In 1939 the Admiralty requisitioned Asturias and Alcantara and had each ship converted into an armed merchant cruiser (AMC).

Asturias was requisitioned on 28 August,[21] shortly before the Second World War broke out. She steamed from Southampton to Belfast to be refitted for the Royal Navy. Her First Class accommodation was removed. Her forward dummy funnel was removed to increase the arc of fire for their anti-aircraft guns. Her deck and hull were strengthened to bear a primary armament of eight BL 6 inch Mk XII naval guns and secondary armament of several QF 3 inch 20 cwt anti-aircraft guns. On 28 September work was completed, she was commissioned as HMS Alcantara with the pennant number F71[21] and sailed to the Royal Navy anchorage at Scapa Flow.[22]

In October 1939 Asturias joined the Halifax Escort Force, escorting transatlantic convoys between Halifax, Nova Scotia and the UK. From November 1939 until April 1940 she served in the Northern Patrol. In May 1940 she returned to convoy work with the North Atlantic Escort Force, but in June she was again switched to the Northern Patrol.[21]

In July 1940 Asturias was transferred to the South Atlantic Station. On 28 January 1941 she was patrolling northeast of Puerto Rico in the western Atlantic when she captured a large Vichy French cargo ship, the 8,199 GRT turbine steamer Mendoza.[21]

Later in 1941 Asturias was upgraded in Newport News, Virginia. Her mainmast was removed to improve her arc of fire and her armament was modernised. Her Second Class accommodation aft was removed and replaced with an aircraft hangar, and she was fitted with an aircraft catapult. She returned to the South Atlantic Station, where for a time she was the area flagship.[23] She remained on the South Atlantic Station until April 1943.[21]

On 28 April 1943 Captain Sir John Meynell Alleyne, Baronet, took command of Asturias. In May she was transferred to the naval arm of the West Africa Command.[21] In July 1943 she left Brazil towing a floating dock to deliver to Freetown in Sierra Leone. On 25 July she was about 400 nautical miles (740 km) from her destination when the Cagni-class Italian submarine Ammiraglio Cagni torpedoed her port side. The explosion was next to Asturias' boiler room, and four members of her crew were killed.[21] An estimated 10,000 tons of water flooded her engine room but she remained afloat. She was towed to Freetown, where the damage was found to be so extensive that she was laid up.[23]

Asturias was written off as a constructive total loss.[23][24] On 30 May 1944 her ownership was transferred to the Ministry of War Transport.[21] She was towed to Gibraltar where she received temporary repairs. By the time these were completed the war had ended. Asturias was towed to Belfast for permanent repairs and conversion back into a civilian passenger liner.[23]

Post-war service

Emigrant ship

After the Second World War British migration to Australia was encouraged. Asturias joined this trade, owned by the Ministry of Transport and managed by RML. She remained in her wartime Royal Navy grey until the end of 1949, when her superstructure was painted white and her one remaining funnel was returned to RML buff. But even then her hull remained grey until May 1950, when it was painted black with pink boot-topping.[23]

Troop ship

Asturias' years as an emigrant ship were interrupted by several voyages as a troop ship. One was in September 1953, when she brought UK troops from South Korea to Gibraltar on their way home from the Korean War.[25] The troops were 530 British soldiers who had been prisoners of war in North Korea. Most were members of the Gloucestershire Regiment who had been captured two and a half years earlier at the Battle of the Imjin River in April 1951. She reached Southampton on 16 September, where her troops were greeted by family members and a large contingent of the Gloucestershire Regiment.[26]

In 1954 she was displaced from emigrant service and transferred to full-time trooping. For this her hull was repainted white with a blue band and her funnel was painted yellow.[23]

Much of Asturias' trooping work was in the Far East.[23] This included her final voyage, when she brought home the First Battalion of the Royal Sussex Regiment from South Korea. She left Inchon on 28 July 1957, called at Hong Kong on 31 July, Singapore on 4 August and Colombo in Sri Lanka on 9 August. She anchored off Aden and then passed through the Suez Canal, which had only recently been cleared of blockships after the 1956 Suez Crisis. She then called at Gibraltar on about 23 August before reaching Southampton on 27 August.[27]

A Night To Remember

Asturias' career ended in 1957. She was sold to Shipbreaking Industries Ltd, and on 14 September she arrived at Faslane to be scrapped.[28]

After Shipbreaking Industries had demolished Asturias' port side, The Rank Organisation used her starboard side to film scenes for the 1958 feature film A Night to Remember. That side was painted in White Star Line livery to represent the 1912 liner RMS Titanic. After filming was completed, Shipbreaking Industries completed her demolition.[29]

References

- ^ "BR 6in 45cal BL Mk XII". NavHist. Flixco Pty Limited. Retrieved 15 May 2017.

- ^ "BR 3in 45cal 12pdr 20cwt QF Mk I To IV". NavHist. Flixco Pty Limited. Retrieved 15 May 2017.

- ^ Nicol 2001b, p. 121.

- ^ Nicol 2001b, p. 233.

- ^ Nicol 2001b, pp. 236–237.

- ^ Nicol 2001b, p. 231.

- ^ Nicol 2001b, p. 232.

- ^ "Asturias". The Yard. Robert C. Retrieved 15 May 2017.

- ^ "Alcantara". The Yard. Robert C. Retrieved 15 May 2017.

- ^ a b Nicol 2001b, p. 131.

- ^ Lloyd's Register, Steamers & Motorships (PDF). London: Lloyd's Register. 1933–34. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- ^ Lloyd's Register, Steamers & Motorships (PDF). London: Lloyd's Register. 1934–35. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- ^ a b c Nicol 2001b, p. 132.

- ^ Talbot-Booth 1942, p. 394.

- ^ a b c Nicol 2001b, p. 139.

- ^ Talbot-Booth 1942, p. 410.

- ^ Talbot-Booth 1942, p. 332.

- ^ a b Nicol 2001b, pp. 138–139.

- ^ a b c Nicol 2001b, p. 140.

- ^ Nicol 2001b, p. 142.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Helgason, Guðmundur (1995–2017). "HMS Asturias (F 71)". uboat.net. Guðmundur Helgason. Retrieved 28 May 2017.

- ^ Nicol 2001b, p. 143.

- ^ a b c d e f g Nicol 2001b, p. 146.

- ^ Nicol 2001a, p. 172.

- ^ Nicol 2001b, pp. 146–147.

- ^ Doherty, Vicky. "Troop Service". SS Asturias. Retrieved 29 May 2017.

- ^ Hamilton, David. "Last Voyage of the Asturias". SS Asturias. Retrieved 29 May 2017.

- ^ Nicol 2001b, p. 147.

- ^ Doherty, Vicky. "From Launch to Scrap – the Asturias Story". SS Asturias. Retrieved 29 May 2017.

Sources and further reading

- Nicol, Stuart (2001a). MacQueen's Legacy; A History of the Royal Mail Line. Vol. 1. Brimscombe Port and Charleston, SC: Tempus Publishing. ISBN 0-7524-2118-2.

- Nicol, Stuart (2001b). MacQueen's Legacy; Ships of the Royal Mail Line. Vol. 2. Brimscombe Port and Charleston, SC: Tempus Publishing. pp. 130–149. ISBN 0-7524-2119-0.

- Osborne, Richard; Spong, Harry & Grover, Tom (2007). Armed Merchant Cruisers 1878–1945. Windsor: World Warship Society. ISBN 978-0-9543310-8-5.

- Talbot-Booth, EC (1942) [1936]. Ships and the Sea (Third ed.). London: Sampson Low, Marston & Co. Ltd.

External links

- Doherty, Vicky. "About This Site". SS Asturias.