Adenosine deaminase

| Adenosine/AMP deaminase | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

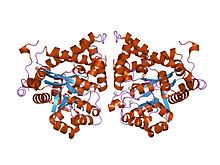

crystal structure of plasmodium yoelii adenosine deaminase (py02076) | |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | A_deaminase | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF00962 | ||||||||

| Pfam clan | CL0034 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR001365 | ||||||||

| PROSITE | PDOC00419 | ||||||||

| SCOP2 | 1add / SCOPe / SUPFAM | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Adenosine deaminase (editase) domain | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | A_deamin | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF02137 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR002466 | ||||||||

| PROSITE | PDOC00419 | ||||||||

| SCOP2 | 1add / SCOPe / SUPFAM | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Adenosine/AMP deaminase N-terminal | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | A_deaminase_N | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF08451 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR013659 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Adenosine deaminase (also known as adenosine aminhydrolase, or ADA) is an enzyme (EC 3.5.4.4) involved in purine metabolism. It is needed for the breakdown of adenosine from food and for the turnover of nucleic acids in tissues.

Present in virtually all mammalian cells, its primary function in humans is the development and maintenance of the immune system.[1] However, the full physiological role of ADA is not yet completely understood.[2]

Structure

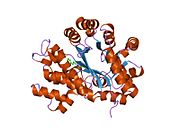

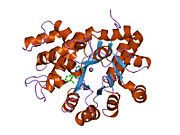

ADA exists in both small form (as a monomer) and large form (as a dimer-complex).[2] In the monomer form, the enzyme is a polypeptide chain,[3] folded into eight strands of parallel α/β barrels, which surround a central deep pocket that is the active site.[1] In addition to the eight central β-barrels and eight peripheral α-helices, ADA also contains five additional helices: residues 19-76 fold into three helices, located between β1 and α1 folds; and two antiparallel carboxy-terminal helices are located across the amino-terminal of the β-barrel.

The ADA active site contains a zinc ion, which is located in the deepest recess of the active site and coordinated by five atoms from His15, His17, His214, Asp295, and the substrate.[1] Zinc is the only cofactor necessary for activity.

The substrate, adenosine, is stabilized and bound to the active site by nine hydrogen bonds.[1] The carboxyl group of Glu217, roughly coplanar with the substrate purine ring, is in position to form a hydrogen bond with N1 of the substrate. The carboxyl group of Asp296, also coplanar with the substrate purine ring, forms hydrogen bond with N7 of the substrate. The NH group of Gly184 is in position to form a hydrogen bond with N3 of the substrate. Asp296 forms bonds both with the Zn2+ ion as well as with 6-OH of the substrate. His238 also hydrogen bonds to substrate 6-OH. The 3'-OH of the substrate ribose forms a hydrogen bond with Asp19, while the 5'-OH forms a hydrogen bond with His17. Two further hydrogen bonds are formed to water molecules, at the opening of the active site, by the 2'-OH and 3'-OH of the substrate.

Due to the recessing of the active inside the enzyme, the substrate once bound is almost completely sequestered from solvent.[1] The surface exposure of the substrate to solvent when bound is 0.5% the surface exposure of the substrate in the free state.

Reactions

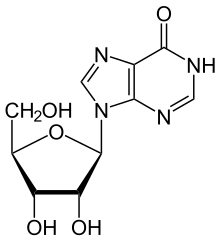

ADA irreversibly deaminates adenosine, converting it to the related nucleoside inosine by the substitution of the amino group for a hydroxyl group.

Inosine can then be deribosylated (removed from ribose) by another enzyme called purine nucleoside phosphorylase (PNP), converting it to hypoxanthine.

Mechanism

Two proposed mechanisms exist for ADA-catalyzed deamination: 1) stereospecific addition-elimination via tetrahedral intermediate or 2) an SN2 reaction.[2][4] By either mechanism, Zn2+ as a strong electrophile activates a water molecule, which is deprotonated by the basic Asp295 to form the attacking hydroxide.[1] His238 orients the water molecule and stabilizes the charge of the attacking hydroxide. Glu217 is protonated to donate a proton to N1 of the substrate.

The reaction is stereospecific due to the location of the zinc, Asp295, and His238 residues, which all face the B-side of the purine ring of the substrate.[1]

Competitive inhibition has been observed for ADA, where the product inosine acts at the competitive inhibitor to enzymatic activity.[5]

Biological Function

ADA is considered one of the key enzymes of purine metabolism.[4] The enzyme has been found in bacteria, plants, invertebrates, vertebrates, and mammals, with high conservation of amino acid sequence.[2] The high degree of amino acid sequence conservation suggests the crucial nature of ADA in the purine salvage pathway.

Primarily, ADA in humans is involved in the development and maintenance of the immune system. However, ADA association has also been observed with epithelial cell differentiation, neurotransmission, and gestation maintenance.[6] It has also been proposed that ADA, in addition to adenosine breakdown, stimulates release of excitatory amino acids and is necessary to the coupling of A1 adenosine receptors and heterotrimeric G proteins.[2]

Pathology

Some mutations in the gene for adenosine deaminase cause it not to be expressed. The resulting deficiency is one cause of Template:SWL (SCID).[7] Deficient levels of ADA have also been associated with pulmonary inflammation, thymic cell death, and defective T-cell receptor signaling.[8][9]

Conversely, mutations causing this enzyme to be overexpressed are one cause of Template:SWL.[10]

There is some evidence that a different allele (ADA2) may lead to autism.[11]

Elevated levels of ADA has also been associated with AIDS.[8][12]

Isoforms

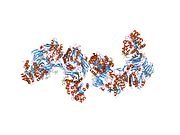

There are 2 isoforms of ADA: ADA1 and ADA2.

- ADA1 is found in most body cells, particularly lymphocytes and macrophages, where it is present not only in the cytosol and nucleus but also as the ecto- form on the cell membrane attached to dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (aka, CD26). ADA1 is involved mostly in intracellular activity, and exists both in small form (monomer) and large form (dimer).[2] The interconversion of small to large forms is regulated by a 'conversion factor' in the lung.[13]

- ADA2 was first identified in human spleen.[14] It was subsequently found in other tissues including the macrophage where it co-exists with ADA1. The two isoforms regulate the ratio of adenosine to deoxyadenosine potentiating the killing of parasites. ADA2 is found predominantly in the human plasma and serum, and exists solely as a homodimer.[15]

- ADAT (ADAT1, ADAT2, ADAT3) is a tRNA-specific ADA, changing the tRNA to allow for a wobble base pairing.

Clinical significance

ADA2 is the predominant form present in human blood plasma and is increased in many diseases, particularly those associated with the immune system: for example rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, and sarcoidosis. The plasma ADA2 isoform is also increased in most cancers. ADA2 is not ubiquitous but co-exists with ADA1 only in monocytes-macrophages.[citation needed]

Total plasma ADA can be measured using high performance liquid chromatography or enzymatic or colorimetric techniques. Perhaps the simplest system is the measurement of the ammonia released from adenosine when broken down to inosine. After incubation of plasma with a buffered solution of adenosine the ammonia is reacted with a Berthelot reagent to form a blue colour which is proportionate to the amount of enzyme activity. To measure ADA2, erythro-9-(2-hydroxy-3-nonyl) adenine (EHNA) is added prior to incubation so as to inhibit the enzymatic activity of ADA1.[14] It is the absence of ADA1 that causes SCID.

ADA can also be used in the workup of lymphocytic pleural effusions or peritoneal ascites, in that such specimens with low ADA levels essentially excludes tuberculosis from consideration.[17]

Tuberculosis pleural effusions can now be diagnosed accurately by increased levels of pleural fluid adenosine deaminase, above 40 U per liter.[18]

Cladribine is an anti-neoplastic agent used in the treatment of hairy cell leukemia; its mechanism of action is inhibition of adenosine deaminase.

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e f g Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 1925539, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=1925539instead. - ^ a b c d e f Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 11223861, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=11223861instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 13062, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=13062instead. - ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 6646173, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=6646173instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 12297022, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=12297022instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 10506947, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=10506947instead. - ^ Sanchez JJ, Monaghan G, Børsting C, Norbury G, Morling N, Gaspar HB (2007). "Carrier frequency of a nonsense mutation in the adenosine deaminase (ADA) gene implies a high incidence of ADA-deficient severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) in Somalia and a single, common haplotype indicates common ancestry". Ann. Hum. Genet. 71 (Pt 3): 336–47. doi:10.1111/j.1469-1809.2006.00338.x. PMID 17181544.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 15705418, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=15705418instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 11435465, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=11435465instead. - ^ Chottiner EG, Cloft HJ, Tartaglia AP, Mitchell BS (1987). "Elevated adenosine deaminase activity and hereditary hemolytic anemia. Evidence for abnormal translational control of protein synthesis". J. Clin. Invest. 79 (3): 1001–5. doi:10.1172/JCI112866. PMC 424261. PMID 3029177.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Persico AM, Militerni R, Bravaccio C; et al. (2000). "Adenosine deaminase alleles and autistic disorder: case-control and family-based association studies". Am. J. Med. Genet. 96 (6): 784–90. doi:10.1002/1096-8628(20001204)96:6<784::AID-AJMG18>3.0.CO;2-7. PMID 11121182.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 3006027, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=3006027instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 893413, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=893413instead. - ^ a b Schrader WP, Pollara B, Meuwissen HJ (January 1978). "Characterization of the residual adenosine deaminating activity in the spleen of a patient with combined immunodeficiency disease and adenosine deaminase deficiency". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 75 (1): 446–50. doi:10.1073/pnas.75.1.446. PMC 411266. PMID 24216.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Cite error: The named reference "pmid24216" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ Zavialov AV, Engstrom A (Oct 2005). "Human ADA2 belongs to a new family of growth factors with adenosine deaminase activity". Biochem. J. 391 (1): 51–57. doi:10.1042/BJ20050683. PMC 1237138. PMID 15926889.

- ^ Keegan LP, Leroy A, Sproul D, O'Connell MA (2004). "Adenosine deaminases acting on RNA (ADARs): RNA-editing enzymes". Genome Biol. 5 (2): 209. doi:10.1186/gb-2004-5-2-209. PMC 395743. PMID 14759252.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ http://erj.ersjournals.com/cgi/content/abstract/21/2/220

- ^ Schwartz's principles of surgery, 8th edition, self assessment and board review, chapter 18 question 16

Further reading

External links

- ADA human gene location in the UCSC Genome Browser.

- ADA human gene details in the UCSC Genome Browser.