Aethiopia

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2016) |

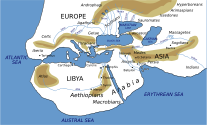

Ancient Aethiopia, (Greek: Αἰθιοπία, romanized: Aithiopía; also known as Ethiopia) first appears as a geographical term in classical documents in reference to the upper Nile region of Sudan, as well as certain areas south of the Sahara desert. Its earliest mention is in the works of Homer: twice in the Iliad,[1] and three times in the Odyssey.[2] The Greek historian Herodotus "specifically" uses the appellation to refer to such parts of sub-Saharan Africa as were then known within the inhabitable world.[3]

In classical antiquity, Africa (or 'Ancient Libya') specifically referred to what is now known as the Maghreb and south of the Libyan Desert and Western Sahara, including all the desert land west of the southern Nile river in North Africa, and not to Sub-Saharan Africa. Geographical knowledge of the continent gradually grew, with the Greek travelogue Periplus of the Erythraean Sea (1st century AD) describing areas along the Red Sea (Erythraean Sea).

Etymology

The Greek name Aithiopia (Αἰθιοπία, from Αἰθίοψ, Aithíops, 'an Ethiopian') is a compound derived of two Greek words: αἴθω, aíthō, 'I burn' + ὤψ, ṓps, 'face'. According to the Perseus Project, this designation properly translates in noun form as burnt-face and in adjectival form as red-brown.[4][5] As such, it was used as a vague term for dark-skinned populations since the time of Homer.[i][6] The term was applied to such peoples when within the range of observation of the ancient geographers, primarily in what was then Nubia (in ancient Sudan). With the expansion of geographical knowledge, the exonym successively extended to certain other areas below the Sahara.

Before Herodotus

Homer (c. 8th century BC) is the first to mention "Aethiopians" (Αἰθίοπες, Αἰθιοπῆες), writing that they are to be found at the east and west extremities of the world, divided by the sea into "eastern" (at the sunrise) and "western" (at the sunset). In Book 1 of the Iliad, Thetis visits Olympus to meet Zeus, but the meeting is postponed, as Zeus and other gods are absent, visiting the land of the Aethiopians.

And in Book 1 of the Odyssey, Athena convinces Zeus to let Odysseus finally return home only because Poseidon is away in Aithiopia and unable to object.

Hesiod (c. 8th century BC) speaks of Memnon as the "king of the Ethiopians."[7]

In 515 BC, Scylax of Caryanda, on orders from Darius I of the Achaemenid Empire, sailed along the Indus River, Indian Ocean, and Red Sea, circumnavigating the Arabian Peninsula. He mentioned "Aethiopians", though his writings on them have not survived.

Hecataeus of Miletus (c. 500 BC) is also said to have written a book about 'Aethiopia,' but his writing is now known only through quotations from later authors. He stated that 'Aethiopia' was located to the east of the Nile, as far as the Red Sea and Indian Ocean. He is also quoted as relating a myth in which the Skiapods ('Shade feet'), whose feet were supposedly large enough to serve as shade, lived there.[citation needed]

In Herodotus

In his Histories (c. 440 BC), Herodotus presents some of the most ancient and detailed information about "Aethiopia".[3] He relates that he personally traveled up the Nile to the border of Egypt as far as Elephantine (modern Aswan). In his view, "Aethiopia" is all of the inhabited land found to the south of Egypt, beginning at Elephantine. He describes a capital at Meroë, adding that the only deities worshipped there were Zeus (Amun) and Dionysus (Osiris). He relates that in the reign of Pharaoh Psamtik I (c. 650 BCE), many Egyptian soldiers deserted their country and settled amidst the Aethiopians.

Herodotus also remarked on the shared cultural practices between Egyptians and Ethiopians as he states: “I myself guessed it to be so, partly because they are dark-skinned and woolly-haired; though that indeed goes for nothing, seeing that other peoples, too, are such; but my better proof was that the Colchians and Egyptians and Ethiopians are the only nations that have from the first practised circumcision”.[8]

Herodotus further noted that there had been 18 Ethiopian kings and one queen among the Egyptian dynasties. [9]

Herodotus tells us that king Cambyses II (c. 570 BC) of the Achaemenid Empire sent spies to the Aethiopians "who dwelt in that part of Libya (Africa) which borders upon the southern sea." They found a strong and healthy people. Although Cambyses then campaigned toward their country, by not preparing enough provisions for the long march, his army completely failed and returned quickly.[10]

In Book 3, Herodotus defines "Aethiopia" as the farthest region of "Libya" (i.e. Africa):[10]

Where the south declines towards the setting sun lies the country called Aethiopia, the last inhabited land in that direction. There gold is obtained in great plenty, huge elephants abound, with wild trees of all sorts, and ebony; and the men are taller, handsomer, and longer lived than anywhere else.

Other Greco-Roman historians

The Egyptian priest Manetho (c. 300 BC) listed Kushite (25th) dynasty, calling it the "Aethiopian dynasty," and Esarhaddon the early 7th century BC ruler of the Neo-Assyrian Empire describes deporting all "Aethiopians" from Egypt upon conquering Egypt from the Nubian Kushite Empire which formed the 25th Dynasty. Moreover, when the Hebrew Bible was translated into Greek (c. 200 BC), the Hebrew appellation "Kush, Kushite" became in Greek "Aethiopia, Aethiopians", appearing as "Ethiopia, Ethiopians" in the English King James Version.[11]

Agatharchides provides a relatively detailed description of the gold mining system of Aethiopia. His text was copied almost verbatim by virtually all subsequent ancient writers on the area, including Diodorus Siculus and Photius.[12]

Diodorus Siculus reported that the Ethiopians claimed that Egypt was an early colony as he writes:

“The Ethiopians say that the Egyptians are one of their colonies which was brought into Egypt by Osiris”.[13]

Diodorus Siculus also discussed the similar cultural practices between the Ethiopians and Egyptians such as the writing systems as he states “We must now speak about the Ethiopian writing which is called hieroglyphic among the Egyptians, in order that we may omit nothing in our discussion of their antiquities”.[14]

Strabo discussed migrations between Egypt and Ethiopia in his book, Geography, and noted that “Egyptians settled Ethiopia and Colchis”.[15] With regard to the Ethiopians, Strabo indicates that they looked similar to Indians, remarking "those who are in Asia (South India), and those who are in Africa, do not differ from each other."[16] Pliny in turn asserts that the place-name "Aethiopia" was derived from one "Aethiop, a son of Vulcan"[16] (the Greek god Hephaestus).[17] He also writes that the "Queen of the Ethiopians" bore the title Kandake, and avers (incorrectly) that the Ethiopians had conquered ancient Syria and the Mediterranean. Following Strabo, the Greco-Roman historian Eusebius claims that the Ethiopians had emigrated into the Red Sea area from the Indus Valley and that there were no people in the region by that name prior to their arrival.[16]

The Greek travelogue from the 1st-century AD, known as the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, initially describes the littoral, based on its author's intimate knowledge of the area. However, the Periplus does not mention any dark-skinned "Ethiopians" among the area's inhabitants. They only later appear in Ptolemy's Geographia in a region far south, around the "Bantu nucleus" of northern Mozambique.

Arrian, wrote in the 1st-century AD that “The appearance of the inhabitants is also not very different in India and Ethiopia: the southern Indians are rather more like Ethiopians as they are black to look on, and their hair is black; only they are not so snub-nosed or woolly-haired as the Ethiopians; the northern Indians are most like the Egyptians physically”.[18][19]

Also the Roman Christian historian and theologian Saint Jerome along with Sophronius referred to Colchis as the "second Ethiopia" because of its 'black-skinned' population.[20]

In literature

Several personalities in Greek and medieval literature were identified as Aethiopian, including several rulers, male and female:

- Memnon and his brother, Emathion, King of Arabia.

- Cepheus and Cassiopeia, parents of Andromeda, were named as king and queen of Aethiopia.

- Homer in his description of the Trojan War mentions several other Aethiopians.

See also

- Aethiopian Sea

- Name of Ethiopia

- Ethiopian historiography

- History of Ethiopia

- Sigelwara Land

- White Aethiopians

- Black people in Ancient Roman history

- Nubia

- Land of Punt

Notes

- ^ “Αἰθιοπῆες” Homer, Iliad, 1.423, whence nom. “Αἰθιοπεύς” Call.Del.208: (αἴθω, ὄψ):—properly, Burnt-face, i.e. Ethiopian, negro, Hom., etc.; prov., Αἰθίοπα σμήχειν 'to wash a blackamoor white', Lucian, Adversus indoctum et libros multos ementem, 28. (Lidell and Scott 1940). Cf. Etymologicum Genuinum s.v. Αἰθίοψ, Etymologicum Gudianum s.v. Αἰθίοψ. "Αἰθίοψ". Etymologicum Magnum (in Greek). Leipzig. 1818.

References

- ^ Homer Iliad I.423; XXIII.206.

- ^ Homer Odyssey I.22-23; IV.84; V.282-7.

- ^ a b For all references to Ethiopia in Herodotus, see: this list at the Perseus Project.

- ^ Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert. "Aithiops". A Greek-English Lexicon. Perseus. Retrieved 2 December 2017.

- ^ Liddell, Henry George, and Robert Scott. 1940. "Αἰθίοψ." In A Greek–English Lexicon, revised and augmented by H. S. Jones and R. McKenzie. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- ^ Fage, John. A History of Africa. Routledge. pp. 25–26. ISBN 1317797272. Retrieved 20 January 2015.

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony, 984–85.

- ^ Herodotus. "The Histories Book II Chapters 99-182". penelope.uchicago.edu.

- ^ Herodotus. "The Histories Book II Chapters 99-182". penelope.uchicago.edu.

- ^ a b Herodotus Histories III.114.

- ^ KJV: Book of Numbers 12 1

- ^ Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. Cambridge University Press for the Royal Asiatic Society. 1892. p. 823. Retrieved 20 January 2015.

- ^ Diop, Cheikh Anta (1974). The African origin of civilization: myth or reality (1st ed.). New York: L. Hill. pp. 1–10. ISBN 1556520727.

- ^ Diodorus Siculus. "The Library of History Book III Chapter 1-14". penelope.uchicago.edu.

- ^ Diop, Cheikh Anta (1974). The African origin of civilization: myth or reality (1st ed.). New York: L. Hill. pp. 1–10. ISBN 1556520727.

- ^ a b c Turner, Sharon (1834). The Sacred History of the World, as Displayed in the Creation and Subsequent Events to the Deluge: Attempted to be Philosophically Considered, in a Series of Letters to a Son, Volume 2. Longman. pp. 480–482. Retrieved 20 January 2015.

- ^ Pliny the Elder Natural History VI.35. "Son of Hephaestus" was also a general Greek epithet meaning "blacksmith".

- ^ Celenko, Theodore (1996). Egypt in Africa. Indianapolis, Ind.: Indianapolis Museum of Art. p. 106. ISBN 0253332699.

- ^ Arrian. Indica. pp. 6:9.

- ^ English, Patrick T. (1959). "Cushites, Colchians, and Khazars". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 18 (1): 49–53. ISSN 0022-2968.