Africville

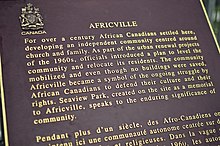

Africville was a small community located on the southern shore of Bedford Basin, in Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada, which existed from the early 1800s to the 1960s, and has been continually occupied from 1970 to the present through a protest on the grounds. Africville is now a commemorative site with a museum. The community has become an important symbol of Black Canadian identity, as an example of the "urban renewal" trend of the 1960s that razed similarly racialized neighbourhoods across Canada, and the struggle against racism.

Africville was founded by Black Nova Scotians from a variety of origins. Many of the first settlers were former slaves from the United States, Black Loyalists who were freed by the Crown during the American Revolutionary War and War of 1812. (The Black community migrated from their community on Albemarle Street, where they had a school established in 1785 that served the Black community for decades under Rev. Charles Inglis.)[1][2]

During the 20th century, Halifax neglected the community, refusing to implement simple services like roads, water, and sewage. The city continued to use the area as an industrial site, notably introducing a waste-treatment facility nearby in 1958. The residents of Africville struggled with poverty and poor health conditions as a result, and the community's buildings became badly deteriorated. During the late 1960s, Halifax condemned the area, relocating its residents to newer housing in order to develop the nearby A. Murray MacKay Bridge, related highway construction, and the Port of Halifax facilities at Fairview Cove to the west.

The site was designated a National Historic Site of Canada in 1996 as being representative of Black Canadian settlements in the province and as an enduring symbol of the need for vigilance in defence of their communities and institutions.[3] After years of protest and investigations, in 2010 the Halifax Council ratified a proposed "Africville Apology", under an arrangement with the federal government, to compensate descendants and their families who had been evicted. In addition, an Africville Heritage Trust was established to design a museum and build a replica of the community church.

History

| History of Halifax, Nova Scotia |

|---|

|

Africville has been claimed as one of "the first free black communities outside of Africa," along with other settlements in Nova Scotia.[4]

The earliest colonial settlement of Africville began with the relocation of Black Loyalists, slaves from the Thirteen Colonies who escaped from rebel masters and were freed by the British in the course of the American Revolutionary War. The Crown transported them and other Loyalists to Nova Scotia, promising land and supplies for their service. The Crown also promised land and equal rights to War of 1812 Refugees.

In 1836, Campbell Road was constructed, creating an access route along the north side of the Halifax Peninsula.[5] The community of Africville was never officially established, but the first land transaction documented on paper was dated 1848. The first two landowners in Africville were William Arnold and William Brown.[4]

Clergyman Richard Preston established the Seaview United African Baptist Church in Africville in 1849, after starting with the Cornwallis Street Baptist Church in 1832 and co-creating a network of Black Baptist churches throughout Nova Scotia called the African United Baptist Association.[6][4] Africville's was one of five in Halifax: Preston (1842), Beechville (1844), Hammonds Plains (1845), Africville, and Dartmouth.

Africville began as a small, poor, self-sufficient rural community of about 50 people during the 19th century. First known as "The Campbell Road Settlement", the community became known as 'Africville' about 1900.[7] Although many people thought it was named Africville because the people who lived there came from Africa, this was not the case. One elderly woman, a resident of Africville, was quoted as saying, "It wasn't Africville out there. None of the people came from Africa…it was part of Richmond (Northern Halifax), just the part where the colour folks lived."[8]

In the late 1850s, the Nova Scotia Railway, later to become the Intercolonial Railway, was built from Richmond to the south, bisecting Africville with the railway's main line along the western shores of Bedford Basin. A second line arrived in 1906 with the arrival of the Halifax and Southwestern Railway, which connected to the Intercolonial at Africville. The Intercolonial Railway, later Canadian National Railways, constructed Basin Yard west of the community, adding more tracks. Trains ran through the area constantly.

The Halifax Explosion

The community had a peak population of 400 at the time of the Halifax Explosion in 1917. At the time, the community's haphazardly positioned dwellings ranged from small, well-maintained, and brightly-painted homes to tiny ramshackle dwellings converted from sheds.[9]

Elevated land to the south protected Africville from the direct blast of the explosion and the complete destruction that levelled the neighbouring community of Richmond. But Africville suffered considerable damage. Four Africville residents (and one Mi'kmaq woman visiting from Queens County, Nova Scotia) were killed by the explosion.[10] A doctor on a relief train arriving at Halifax noted Africville residents "as they wandered disconsolately around the ruins of their still standing little homes".[11]

In the aftermath of the disaster, Africville received modest relief assistance from the city, but none of the reconstruction and none of the modernization invested into other parts of the city at that time.[12][page needed]

Beginning in the early 20th century around the Great War, more people moved there, drawn by jobs in industries and related facilities developed nearby.[citation needed]

Daily life

Economically, the first two generations were not prosperous. Many men found employment in low-paying jobs. Others worked as seamen or Pullman porters, who would clean and work on train cars. This steady employment on the Pullman cars was considered prestigious at the time, as the men also got to travel and see the country. Only 35 percent of labourers had regular employment, and 65 percent of the people worked as domestic servants.[13] They had limited opportunities. Women were also hired as cooks, to clean the hospital or prison, and some elderly women were hired to clean upper-class houses.

The community was neglected in terms of education. The city built the first elementary school here in 1883, at the expense of community residents. It was a poor community, so up until 1933 none of the teachers had obtained formal training.[14] Only 40 percent of boys and girls received any education at all, as many families needed to have them help with paid work, or taking care of younger siblings at home so parents could work. Out of the 140 children ever registered, 60 children reached either grade 7 or 8, and only four boys and one girl reached grade 10.[15]

To understand Africville, "you got to know about the church."[16] The Seaview African United Baptist Church was established at Africville in 1849; it joined with other black Baptist congregations to establish the African Baptist Association in 1854. The community's social life revolved around the church, which was the place of baptisms, weddings and funerals. Other black groups came to Africville for Sunday picnics and events. Everything was done through the church, "clubs, youth organizations, ladies' auxiliary and Bible classes".[17] The church was the life and heart of the town.

The Africville Seasides hockey team of the pioneering Colored Hockey League (1894–1930) won the championship in 1901 and 1902. The team beat West End Rangers from PEI to retain their title in a 3-2 single game victory in February 1902, and were led by star goaltender William Carvery, his two brothers on the team, plus three Dixon brothers also on the squad.

Relationship with Halifax

Throughout its history, Africville was confronted with isolation. The town never received proper roads, health services, water, street lamps or electricity. Residents protested to the city and called for municipal water supply and treatment of sewage, to no avail, and the lack of these services had serious adverse health implications for residents. Contamination of the wells was so frequent that residents had to boil their water before using it for drinking or cooking.

From the mid-19th century, the City of Halifax located its least desirable facilities in the Africville area, where the people had little political power and property values were low. A prison was built there in 1853, an infectious disease hospital in 1870, a slaughterhouse, and even a depository for fecal waste from nearby Russellville.

In 1958 the city decided to move the town garbage dump and landfill to the Africville area. While the residents knew they could not legally fight this, they illegally salvaged the dump for usable goods. They would get clothes, copper, steel, brass, tin, etc. The dump contributed to the city's classifying this area as an official slum.[18]

Razing

During the 1940s and 1950s in different parts of Canada, the federal, provincial and municipal governments were working together for urban renewal: to redevelop areas classified as slums and relocate the people to new and improved housing.[19] The intent was to redevelop some land for "higher" uses with greater economic return: business and industry. Notable fellow racialized neighbourhoods razed under the banner of urban renewal include The Ward in Toronto, and Rooster Town in Winnipeg.[20] Scholars see the razing of Africville as a confluence of "overt and hidden racism, the progressive impulse in favour of racial integration, and the rise of liberal-bureaucratic social reconstruction ideas."[21]

Many years earlier, and again in 1947 after a major fire burnt several Africville houses, officials discussed redevelopment and relocation of Africville. Concrete plans of relocation did not officially emerge until 1961. Stimulated by the Stephenson Report of 1957 and the City's establishing its Department of Development in 1961, it proposed relocation of these residents.

In 1962 Halifax adopted the relocation proposal unanimously, and the Rose Report, published in 1964, was passed 37/41 in favour of relocation.[22]

The formal relocation took place mainly between 1964 and 1967. The residents were assisted in their move by Halifax transporting them and their goods using the city's dump trucks. This image forever stuck in the minds and hearts of people; they took it to represent the degrading way they were treated before, during, and after the move.

Many residents

now believe that the city council had no plans to turn Africville into an industrial site, and that racism was at the heart and soul of the destruction of Africville. Their belief is that the city fathers simply wanted to remove from the urban community of Halifax a concentrated mass of Black people for whom they had no regard. Because of the city's continued negative response to the people of Africville, the community failed to develop, and this failure was used as a rationale to destroy it.[23]

There were many hardships, suspicion and jealousy that emerged, mostly due to complications of land and ownership claims. Only 14 residents held clear legal titles to their land. Those with no legal rights were given a $500 payment and promised a furniture allowance, social assistance, and public housing units.[24]

Young families felt they had enough money to begin a new life, but most of the elderly residents would not budge; they had much more of an emotional connection to their homes. They were filled with grief and felt cheated out of their property. Resistance to eviction became more difficult as residents accepted the buyouts and their homes were demolished. The city quickly demolished each house as soon as residents moved out. Occasionally the city would demolish a house whenever an opportunity presented itself - such as when a resident was in the hospital.[23]

The church at Africville was demolished at night to avoid controversy, on November 20, 1967, a year before the city officially possessed the building.[25] There is controversy around the documentation, which shows the church was sold in 1968; the page has been edited by hand to forge the sale as a year earlier.[25][26] Internal city government documents show the demolition order being sent in 1967, with a claim that the building was dangerous.[25] At the time, it was still in use: residents remember the church being bulldozed in 1967, shortly after the last active service; another service was being planned for the end of the year.[26][27] It was bulldozed with many residents' documentation inside, such as birth, marriage, and death records, which could have established chains of custody for land claims. The last Africville home was demolished on January 2, 1970.[28]

After relocation to public housing within the city limits, the residents had new problems. The cost of living went up in their new homes, more people were unemployed and without regular incomes, none of the promised employment or education programs were implemented, and the city's promises were fulfilled:

Benefits were so modest as to be virtually irrelevant…within a year and a half this post-relocation program lay in ruins.[29]

Family strains and debt forced many to rely on public assistance, and anxiety was high among the former residents. One of the biggest complaints was that "they feel no sense of ownership or pride in the sterile public housing projects."[30]

Post-razing legacy

Part of the former territory of Africville is occupied by a highway interchange that serves the A. Murray MacKay Bridge. The port development at Fairview Cove did not extend as far east as Africville, leaving its historic waterfront intact.

In light of the controversy related to the relocation, the city of Halifax created the Seaview Memorial Park on the site in the 1980s, preserving it from development. The park was most often used as an off-leash dog park.

Former Africville residents carried out periodic protests at the park throughout the 1980s and 1990s.[31] Eddie Carvery has been living on the Africville site since 1970 in protest of the razing, despite city officials seizing his trailers several times.[32]

The Africville Genealogy Society was formed in 1983 to track former residents and their descendants.[33]

Africville apology

In May 2005, New Democratic Party of Nova Scotia MLA Maureen MacDonald introduced a bill in the provincial legislature called the Africville Act. The bill called for a formal apology from the Nova Scotia government, a series of public hearings on the destruction of Africville, and the establishment of a development fund to go towards historical preservation of Africville lands and social development in benefit of former residents and their descendants. Halifax mayor Peter Kelly has offered land, some money, and various other services for a replica of the Seaview African United Baptist Church. After the offer was made in 2002, the Africville Genealogy Society requested some alterations to the Halifax offer, including additional land and the possibility of building affordable housing near the site. The Africville site was declared a national historic site in 2002.

On February 23, 2010 the Halifax Council ratified a proposed "Africville apology" with an arrangement with the Government of Canada to establish a $250,000 Africville Heritage Trust to design a museum and build a replica of the community church.[34] The dedicated site was a 2.5-acre area.[35]

On 24 February 2010 Halifax Mayor Peter Kelly made the Africville Apology, apologizing for the eviction as part of a $4.5-million compensation deal. The City restored the name Africville to Seaview Park at the annual Africville Family Reunion on July 29, 2011.[36]

Africville Museum

A building designed to mimic the Seaview African United Baptist Church, demolished in 1969, was built in the summer of 2011 to serve as a museum and historic interpretation centre. The nearly complete church was ceremonially opened on September 25, 2011.[37] The opening ceremonies included a gospel concert, several church services, and the release of a compilation audio album with archival recordings of songs sung in Africville.[38]

Since then, the Museum has given tours of the site, put on a number of exhibits, commissioned a play about the beginnings of Africville, and organized a number of fundraisers and petitions, including to add a transit stop at and accessibility improvements to the museum.[39][4]

The Africville Museum continues to have problems with area use, including local residents who continue to use Seaview Park as a dog park; and vandals, who are graffitiing signs, are disrupting trust efforts to identify the sites of former houses.[40][41][42]

Lawsuit

Some former residents and their descendents have filed a civil lawsuit seeking individual compensation for property in Africville.[43][44]

Tributes and related media

African Canadian singer songwriter Faith Nolan released an album in 1986 called Africville.

In 1989, a historic exhibit about Africville toured across Canada. It has evolved into a permanent exhibit on display at Nova Scotia's Black Cultural Centre in Preston.

In 1991, the National Film Board of Canada released the documentary film, Remember Africville, which received the Moonsnail Award for best documentary at the Atlantic Film Festival.[45]

Montreal-born jazz pianist Joe Sealy released a CD of original music, Africville Suite, in 1996. It won a Juno Award in 1997. It includes twelve pieces reflecting on places and activities in Africville, where Sealy's father was born. Sealy was working and living in Halifax during the time of the destruction of the community, and began the suite in memory of his father.

Canadian jazz pianist Trevor Mackenzie released the album, Ain't No Thing Like a Chicken Wing, in 1997 as a tribute to the neighbourhood where his father grew up.

In 1998, Eastern Front Theatre produced a play by George Boyd, Consecrated Ground, which dramatized the Africville eviction. In 2000, the play was nominated for a Governor-General's award for English-Language Drama. The story of Africville has also influenced the work of George Elliott Clarke.[46]

In 2006, Dundurn Press published Last Days in Africville (by Dorothy Perkyns), a fictional account of life for a young Africville girl at the time of its destruction.

In 2007, the Newfoundland metal/hardcore band Bucket Truck released a video for their song "A Nourishment by Neglect", which details the events surrounding the destruction of the Africville community.

Also in 2007, Heritage Canada began funding an independently produced documentary, "Stolen From Africville" [1], written and directed by well-known Canadian activist and performer Neil Donaldson and Sourav Deb ([2]). Scheduled for a summer 2008 release, the film follows the lives of those displaced from the Africville community over the course of a year.

Additionally, in 2007, Canadian hip hop group Black Union released a song featuring Maestro about the historic community of Africville. The music video was recorded in Seaview Park (now Africville Park). The video has over 50,000 views on YouTube.[47]

On June 15, 2009, the Rev. Jesse Jackson, a noted American civil rights activist, was presented with the book about Africville, at the Nova Scotia Alliance of Black School Educators. Irvine Carvery, president of the Africville Genealogy Society, made the presentation[48] in his capacity as chair of the Halifax Regional School Board.

The Hermit of Africville, a biography of longtime Africville protester Eddie Carvery, was published by Pottersfield Press in 2010.[49] In 2011, Nimbus Publishing/Vagrant Press published Stephens Gerard Malone's novel Big Town, a fictional account related to the eviction of residents and the razing of Africville.

Notable residents

- Addie Aylestock - church deaconess

- Parents of Mildred Dixon - professional dancer at the Cotton Club; Dixon was born in Boston, where her parents had moved in the early 20th century

- Clara Carvery Adams - namesake of Duke Ellington's song "Clara," written in 1964 and rediscovered in 1999[50]

- Eddie Carvery

- George Dixon (boxer)

See also

- Jennifer Rosanne States, Nova Scotia 20th-century discrimination case

- Viola Desmond, a Nova Scotia woman who sat in a white area of a theatre

- Nova Scotia Heritage Day

- Black Nova Scotians

References

- ^ pp. 71-72

- ^ https://www.smu.ca/webfiles/fingard-educationofthepoorinhfx-1973.pdf

- ^ Africville. Canadian Register of Historic Places. Retrieved 25 August 2012.

- ^ a b c d "Africville from the beginning". The Chronicle Herald. 2014-09-18. Retrieved 2018-02-14.

- ^ ""1836" Timeline Africville Genealogy Society Website". Archived from the original on 2010-11-15. Retrieved 2010-12-09.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Canadian Biography - Richard Preston

- ^ Alfreda Withrow, One City, Many Communities, Nimbus Publishing, Halifax (1999), p. 11

- ^ Africville Genealogy Society. The Spirit of Africville. (Halifax: Formac Publishing Company Limited, 1992)

- ^ Donald H. Clairmont & Dennis William Magill, Africville: The Life and Death of a Canadian Black Community, Canadian Scholars' Press, Toronto (1999), pp. 44-45.

- ^ "Halifax Explosion Book of Remembrance". Archived from the original on 2008-12-08. Retrieved 2009-03-04.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Personal Narrative Dr. W.B. Moore", The Halifax Explosion December 6, 1917, Graham Metson, McGraw-Hill Ryerson Limited, 1978, p. 107

- ^ Michelle Hebert Boyd, Enriched by Catastrophe: Social Work and Social Conflict after the Halifax Explosion (Halifax: Fernwood Publishing 2007)

- ^ Africville Genealogy Society. The Spirit of Africville. (Halifax: Formac Publishing Company Limited, 1992), Page 17.

- ^ Donald Clairmont & Dennis William Magill. Africville: The Life and Death of a Canadian Black Community. (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart Limited, 1974), Page 110.

- ^ Donald Clairmont & Dennis William Magill. Africville: The Life and Death of a Canadian Black Community. (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart Limited, 1974) Page 111.

- ^ Africville Genealogy Society. The Spirit of Africville. (Halifax: Formac Publishing Company Limited, 1992) Page 27.

- ^ Africville Genealogy Society. The Spirit of Africville. (Halifax: Formac Publishing Company Limited, 1992), Page 25.

- ^ Donald Clairmont & Dennis William Magill. Africville: The Life and Death of a Canadian Black Community. (Toronto:McClelland and Stewart Limited, 1974)

- ^ Tina Loo. "Africville and the Dynamics of State Power in Postwar Canada", Acadiensis, 2010

- ^ Burley, David G. (2013). "Rooster Town: Winnipeg's Lost Métis Suburb, 1900–1960". Urban History Review. 42 (1). doi:10.7202/1022056ar. ISSN 0703-0428.

- ^ "TURNING POINTS: The Razing of Africville an epic failure in urban community renewal". The Chronicle Herald. 2017-11-18. Retrieved 2018-02-14.

- ^ James W. St. G. Walker. "Allegories and Orientations in African-Canadian Historiography: The Spirit of Africville." (Dalhousie Review, Summer 97, Vol 77, Issue 2, P155, 25p) Page 160.

- ^ a b Carvery, Irvine (2008). "Africville: A Community Displaced". Collections Canada. Retrieved 2018-02-14.

- ^ Donald Clairmont, & Dennis William McGill. Africville: The Life and Death of a Canadian Black Community. (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart Limited, 1974) Page 67.

- ^ a b c "Exclusive: Documents solve mystery surrounding Africville church's demolition date". Atlantic. 2017-03-08. Retrieved 2018-02-14.

- ^ a b "Africville church: The demolition of the heartbeat of a community". Atlantic. 2017-03-04. Retrieved 2018-02-14.

- ^ "Restoring Africville's heart | Halifax Magazine". halifaxmag.com. Retrieved 2018-02-14.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-10-01. Retrieved 2011-09-29.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) "Africville: Canada's Most Famous Black Community", DeCosta 400 - ^ African Genealogy Society. The Spirit of Africville. (Halifax: Formac Publishing Company Limited, 1992) Page 73.

- ^ Clyde, Farnsworth. Uprooted and Now Withered by Public Housing. (New York: H.J. Raymond & Co. New York, 1995) Page 1.

- ^ John Tattrie, The Hermit of Africville, Pottersfield Press, Halifax (2010)

- ^ "Africville: Canada's Secret Racist History". Vice. 2013-02-04. Retrieved 2018-02-14.

- ^ "Faithful gathering in Africville". The Chronicle Herald. 2017-05-30. Retrieved 2018-02-14.

- ^ "CBC News - Nova Scotia - Halifax council ratifies Africville apology". Cbc.ca. 2010-02-23. Archived from the original on 24 February 2010. Retrieved 2010-03-25.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "The Story " Africville Museum "". africvillemuseum.org. Retrieved 2018-02-14.

- ^ Halifax park renamed Africville", CBC News, July 29, 2011

- ^ "Africville replica church celebrated", CBC News, Sept 25, 2011; Dan Arsenault, "Tears and memories mark Africville church opening", Halifax Chronicle Herald, Sept. 26, 2011

- ^ "Africville church commemorated, 50 years after demolition". CBC News. Retrieved 2018-02-14.

- ^ "Africville Museum visitors shocked by lack of transit accessibility". CBC News. Retrieved 2018-02-14.

- ^ Omand, Geordon (2014-07-13). "Dog park debate stirs anger in Halifax black community". CTVNews. Retrieved 2018-02-14.

- ^ "Make things right in Africville | Halifax Magazine". halifaxmag.com. Retrieved 2018-02-14.

- ^ "Africville Museum". business.facebook.com. Retrieved 2018-02-14.

- ^ "Africville Residents Want Compensation for the Homes Halifax Bulldozed Decades Ago". Vice. 2015-02-24. Retrieved 2018-02-14.

- ^ Thomson, Aly (2015-02-24). "Africville residents seek changes to proposed lawsuit against Halifax". CTVNews. Retrieved 2018-02-14.

- ^ "Remember Africville". Collection page. National Film Board of Canada. Retrieved 10 March 2010.

- ^ Collette, Thomas (2016-07-23). "Africville: the death of a community for the renewal of an identity" (Winning essay - VIU English Department Competition 2015-2016): 7 p. – via VIUSpace.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Black Union Ft. Maestro - Africville". YouTube. 2007-08-13. Retrieved 2010-03-25.

- ^ "The Africville Genealogy Society". Africville.ca. Archived from the original on 2010-10-15. Retrieved 2010-03-25.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2010-07-24. Retrieved 2010-07-15.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Marilyn Smulders, "Ellington song found/ Local Journalist finds piece written for Halifax woman", The Daily News, 4 June 1999, accessed 4 April 2015

External links

- Africville: The Spirit Lives On - The Africville Genealogy

- "Africville: Expropriating Nova Scotia's blacks", CBC Digital Archives

- Gone but Never Forgotten: Bob Brooks' Photographic Portrait of Africville in the 1960s, Nova Scotia Archives & Records Management

- STOLEN FROM AFRICVILLE: Broken Homes, Broken Hearts, a documentary on the lives and history of those who lived in the Africville settlement, official website

- Documentary on the History of Africville

- TheCyberKrib.com Interview by Neil Acharya with author Stephen Kimber about his novel, Reparations: A Story of Africville

- Watch Remember Africville at NFB,ca

- "Eddie Carvery, Africville and the Longest Civil Rights Protest in Canadian History", Transmopolis, July 2010