Canaanite religion

Canaanite religion refers to the group of Ancient Semitic religions practiced by the Canaanites living in the ancient Levant from at least the early Bronze Age through the first centuries of the Common Era.

Canaanite religion was polytheistic, and in some cases monolatristic.

Beliefs

Deities

A great number of deities were worshipped by the followers of the Canaanite religion; this is a partial listing:

- Anat, virgin goddess of war and strife, sister and putative mate of Ba'al Hadad

- Athirat, "walker of the sea", Mother Goddess, wife of El (also known as Elat and after the Bronze Age as Asherah)

- Athtart, better known by her Greek name Astarte, assists Anat in the Myth of Ba'al

- Attar, god of the morning star ("son of the morning") who tried to take the place of the dead Baal and failed. Male counterpart of Athtart.

- Baalat or Baalit, the wife or female counterpart of Baal (also Belili)

- Baal Hadad (lit. master of thunder), storm god. Often referred to as Baalshamin.

- Baal Hammon, god of fertility and renewer of all energies in the Phoenician colonies of the Western Mediterranean

- Dagon, god of crop fertility and grain, father of Ba'al Hadad

- El, also called 'Il or Elyon ("Most High"), generally considered leader of the pantheon

- Eshmun, god, or as Baalat Asclepius, goddess, of healing

- Ishat, goddess of fire. She was slain by Anat.[1][2][3]

- Kotharat, goddesses of marriage and pregnancy

- Kothar-wa-Khasis, the skilled, god of craftsmanship

- Lotan, the twisting, seven-headed serpent ally of Yam

- Marqod, God of Dance

- Melqart, Literally "king of the city", God of Tyre, the underworld and cycle of vegetation in Tyre

- Moloch, putative god of fire[4]

- Mot or Mawat, god of death (not worshiped or given offerings)

- Nikkal-wa-Ib, goddess of orchards and fruit

- Qadeshtu, lit. "Holy One", putative goddess of love. Also a title of Asherah.

- Resheph, god of plague and of healing

- Shachar and Shalim, twin mountain gods of dawn and dusk, respectively. Shalim was linked to the netherworld via the evening star and associated with peace[5]

- Shamayim, (lit. "Skies"), god of the heavens, paired with Eretz, the land or earth.

- Shapash, also transliterated Shapshu, goddess of the sun; sometimes equated with the Mesopotamian sun god Shamash,[6] whose gender is disputed. Some authorities consider Shamash a goddess [7]

- Sydyk, the god of righteousness or justice, sometimes twinned with Misor, and linked to the planet Jupiter[8][9]

- Yam (lit. sea-river) the god of the sea and the river,[10] also called Judge Nahar (judge of the river).[11][12][13]

- Yarikh, god of the moon and husband of Nikkal

Compare with list at Tour Egypt: http://m.touregypt.net/godsofegypt/

Afterlife beliefs and Cult of the Dead

Canaanites believed that following physical death, the npš (usually translated as "soul") departed from the body to the land of Mot (Death). Bodies were buried with grave goods, and offerings of food and drink were made to the dead to ensure that they would not trouble the living. Dead relatives were venerated and sometimes asked for help.[14][15]

Cosmology

None of the inscribed tablets found in 1929 in the Canaanite city of Ugarit (destroyed ca. 1200 BC) has revealed a cosmology. Any idea of one is often reconstructed from the much later Phoenician text by Philo of Byblos (c. 64–141 AD), after much Greek and Roman influence in the region.

According to the pantheon, known in Ugarit as 'ilhm (=Elohim) or the children of El, supposedly obtained by Philo of Byblos from Sanchuniathon of Berythus (Beirut) the creator was known as Elion, who was the father of the divinities, and in the Greek sources he was married to Beruth (Beirut = the city). This marriage of the divinity with the city would seem to have Biblical parallels too with the stories of the link between Melqart and Tyre; Chemosh and Moab; Tanit and Baal Hammon in Carthage.

From the union of El Elyon and his consort were born Uranus and Ge, Greek names for the "Heaven" and the "Earth".

In Canaanite mythology there were twin mountains Targhizizi and Tharumagi which hold the firmament up above the earth-circling ocean, thereby bounding the earth. W. F. Albright, for example, says that El Shaddai is a derivation of a Semitic stem that appears in the Akkadian shadû ("mountain") and shaddā`û or shaddû`a ("mountain-dweller"), one of the names of Amurru. Philo of Byblos states that Atlas was one of the Elohim, which would clearly fit into the story of El Shaddai as "God of the Mountain(s)." Harriet Lutzky has presented evidence that Shaddai was an attribute of a Semitic goddess, linking the epithet with Hebrew šad "breast" as "the one of the Breast". The idea of two mountains being associated here as the breasts of the Earth, fits into the Canaanite mythology quite well. The ideas of pairs of mountains seem to be quite common in Canaanite mythology (similar to Horeb and Sinai in the Bible). The late period of this cosmology makes it difficult to tell what influences (Roman, Greek, or Hebrew) may have informed Philo's writings.

Mythology

In the Baal Cycle, Ba'al Hadad is challenged by and defeats Yam, using two magical weapons (called "Driver" and "Chaser") made for him by Kothar-wa-Khasis. Afterward, with the help of Athirat and Anat, Ba'al persuades El to allow him a palace. El approves, and the palace is built by Kothar-wa-Khasis. After the palace is constructed, Ba'al gives forth a thunderous roar out of the palace window and challenges Mot. Mot enters through the window and swallows Ba'al, sending him to the Underworld. With no one to give rain, there is a terrible drought in Ba'al's absence. The other deities, especially El and Anat, are distraught that Ba'al has been taken to the Underworld. Anat goes to the Underworld, attacks Mot with a knife, grinds him up into pieces, and scatters him far and wide. With Mot defeated, Ba'al is able to return and refresh the Earth with rain.[16]

Religious practices

Archaeological investigations at the site of Tell el-Safiad have found the remains of donkeys, as well as some sheep and goats in Early Bronze Age layers, dating to 4900 years ago which were imported from Egypt in order to be sacrificed. One of the sacrificial animals, a complete donkey, was found beneath the foundations of a building, leading to speculation this was a 'foundation deposit' placed before the building of a residential house.[17]

It is considered virtually impossible to reconstruct a clear picture of Canaanite religious practices. Although child sacrifice was known to surrounding peoples there is no reference to it in ancient Phoenician or Classical texts. The biblical representation of Canaanite religion is always negative.[18]

Canaanite religious practice had a high regard for the duty of children to care for their parents, with sons being held responsible for burying them, and arranging for the maintenance of their tombs.[19]

Canaanite deities such as Baal were represented by figures which were placed in shrines often on hilltops, or 'high places' surrounded by groves of trees, such as is condemned in the Hebrew Bible, in Hosea (v 13a) which would probably hold the Asherah pole, and standing stones or pillars.[20]

History

The Canaanites

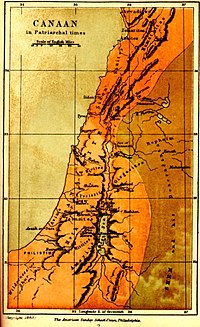

The Levant region was inhabited by people who themselves referred to the land as 'ca-na-na-um' as early as the mid-third millennium BCE.[21] There are a number of possible etymologies for the word.

Some[who?] suggest the name comes from the Semitic word "cana'ani", meaning merchant, for which the Phoenicians became justly famous.

The Akkadian word "kinahhu" referred to the purple-colored wool, dyed from the Murex molluscs of the coast, which was throughout history a key export of the region. When the Greeks later traded with the Canaanites, this meaning of the word seems to have predominated as they called the Canaanites the Phoenikes or "Phoenicians", which may derive from the Greek word "Phoenix" meaning crimson or purple, and again described the cloth for which the Greeks also traded. The Romans transcribed "phoenix" to "poenus", thus calling the descendants of the Canaanite settlers in Carthage "Punic".

Thus while "Phoenician" and "Canaanite" refer to the same culture, archaeologists and historians commonly refer to the Bronze Age, pre-1200 BC Levantines as Canaanites and their Iron Age descendants, particularly those living on the coast, as Phoenicians. More recently, the term Canaanite has been used for the secondary Iron Age states of the interior (including the Philistines and the states of Israel and Judah) that were not ruled by Arameans — a separate and closely related ethnic group.[22]

Influences

Canaanite religion was strongly influenced by their more powerful and populous neighbors, and shows clear influence of Mesopotamian and Egyptian religious practices. Like other people of the Ancient Near East Canaanite religious beliefs were polytheistic, with families typically focusing on Veneration of the dead in the form of household gods and goddesses, the Elohim, while acknowledging the existence of other deities such as Baal and El, Asherah and Astarte. Kings also played an important religious role and in certain ceremonies, such as the hieros gamos of the New Year, may have been revered as gods. "At the center of Canaanite religion was royal concern for religious and political legitimacy and the imposition of a divinely ordained legal structure, as well as peasant emphasis on fertility of the crops, flocks, and humans."[23] [24]

Contact with other areas

This section possibly contains original research. (January 2015) |

Canaanite religion was influenced by its peripheral position, intermediary between Egypt and Mesopotamia, whose religions had a growing impact upon Canaanite religion. For example, during the Hyksos period, when chariot-mounted maryannu ruled in Egypt, at their capital city of Avaris, Baal became associated with the Egyptian god Set, and was considered identical – particularly with Set in his form as Sutekh. Iconographically henceforth Baal was shown wearing the crown of Lower Egypt and shown in the Egyptian-like stance, one foot set before the other. Similarly Athirat (known by her later Hebrew name Asherah), Athtart (known by her later Greek name Astarte), and Anat henceforth were portrayed wearing Hathor-like Egyptian wigs.

From the other direction, Jean Bottéro has suggested that Yah of Ebla (a possible precursor of Yam) was equated with the Mesopotamian god Ea during the Akkadian Empire. In the Middle and Late Bronze Age, there are also strong Hurrian and Mitannite influences upon the Canaanite religion. The Hurrian goddess Hebat was worshiped in Jerusalem, and Baal was closely considered equivalent to the Hurrian storm god Teshub and the Hittite storm god, Tarhunt. Canaanite divinities seem to have been almost identical in form and function to the neighboring Arameans to the east, and Baal Hadad and El can be distinguished amongst earlier Amorites, who at the end of the Early Bronze Age invaded Mesopotamia.

Carried west by Phoenician sailors, Canaanite religious influences can be seen in Greek mythology, particularly in the tripartite division between the Olympians Zeus, Poseidon and Hades, mirroring the division between Baal, Yam and Mot, and in the story of the Labours of Hercules, mirroring the stories of the Tyrian Melqart, who was often equated with Heracles.

Hebrew Bible

El Elyon also appears in Baalam's story in Numbers and in Moses song in Deuteronomy 32:8. The Masoretic Texts say, "When the Most High (`Elyōn) divided to the nations their inheritance, he separated the sons of man (Ādām); he set the bounds of the people according to the number of the sons of Israel."

Sources

The sources for Canaanite religion are literary sources, mainly from Late Bronze Age Ugarit[25] and supplemented by biblical sources, and from archaeological discoveries.

Literary sources

Until the excavation of Ras Shamra in Northern Syria (the site historically known as Ugarit), and the discovery of its Bronze Age archive of clay tablets written in a alphabetical cuneiform excavated by Claude F. A. Schaefer,[26] little was known of Canaanite religion, as papyrus seems to have been the preferred writing medium. Unlike in Egypt, where papyrus may survive centuries in the extremely dry climate, these have simply decayed in the humid Mediterranean climate.[27] As a result, the accounts contained within the Bible were almost the only sources of information on ancient Canaanite religion. This was supplemented by a few secondary and tertiary Greek sources (Lucian's De Dea Syria (The Syrian Goddess), fragments of the Phoenician History of Philo of Byblos, and the writings of Damascius). More recently detailed study of the Ugaritic material, other inscriptions from the Levant and also of the Ebla archive from Tel Mardikh, excavated in 1960 by a joint Italo-Syrian team, have cast more light on the early Canaanite religion.[27][28]

According to The Encyclopedia of Religion, the Ugarit texts were one part of a larger religion, that was based on the religious teachings of Babylon. The Canaanite scribes that produced the Baal texts were also trained to write in Babylonian cuniform, including Sumerian and Akkadian texts of every genre.[29]

Archaeological sources

Archaeological excavations in the last few decades have unearthed more about the religion of the ancient Canaanites.[22] The excavation of the city of Ras Shamra and the discovery of its Bronze Age archive of clay tablet alphabetic cuneiform texts, helped provide a wealth of new information. More recently, detailed study of the Ugaritic material, other inscriptions from the Levant and also of the Ebla archive from Tel Mardikh, excavated in 1960 by a joint Italo-Syrian team, have cast more light on the early Canaanite religion.

See also

References

- ^ Gorelick, Leonard; Williams-Forte, Elizabeth; Ancient seals and the Bible. International Institute for Mesopotamian Area Studies. p.32

- ^ Dietrich, Manfried; Loretz, Oswald; Ugarit-Forschungen: Internationales Jahrbuch für die Altertumskunde Syrien-Palästinas, Volume 31. p.362

- ^ Kang, Sa-Moon, Divine war in the Old Testament and in the ancient Near East. p.79

- ^ "alleged but not securely attested", according to Johnston, Sarah Isles, Religions of the Ancient World: A Guide. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-01517-7. p.335

- ^ Botterweck, G.J.; Ringgren, H.; Fabry, H.J. (2006). Theological Dictionary of the Old Testament. Vol. 15. Alban Books Limited. p. 24. ISBN 9780802823397. Retrieved 2014-12-15.

- ^ Johnston, Sarah Isles, Religions of the Ancient World: A Guide. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-01517-7. P. 418

- ^ Wyatt, Nick, There's Such Divinity Doth Hedge a King, Ashgate (19 Jul 2005), ISBN 978-0-7546-5330-1, p. 104

- ^ "26 Religions". cs.utah.edu. Retrieved 2014-10-01.

- ^ "MELCHIZEDEK - JewishEncyclopedia.com". jewishencyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2014-10-01.

- ^ Ugaritic text: KTU 1.1 IV 14

- ^ "The Shelby White & Leon Levy Program: Dig Sites, Levant Sothern". fas.harvard.edu. Retrieved 2014-10-01.

- ^ Finkelstein, Israel, and Silberman, Neil Asher, 2001, The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology's New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Its Sacred Texts, p. 242

- ^ Asherah: goddesses in Ugarit, Israel and the Old Testament, By Tilde Binger. Page 35

- ^ Segal, Alan F. Life after death: a history of the afterlife in the religions of the West

- ^ Annette Reed (11 February 2005). "Life, Death, and Afterlife in Ancient Israel and Canaan" (PDF). Retrieved 2014-10-01.[dead link]

- ^ Wilkinson, Philip Myths & Legends: An Illustrated Guide to Their Origins and Meanings

- ^ http://www.haaretz.com/jewish/archaeology/1.726027

- ^ Title = Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible | Authors = David Noel Freedman, Allen C. Myers | Publisher = Amsterdam University Press | Date = 31 Dec 2000 | Pg = 214

- ^ Title = Reading the Old Testament: An Introduction | Authors = Lawrence Boadt, Richard J. Clifford, Daniel J. Harrington | Publisher = Paulist Press | Date = 2012 | page = Chapter 11

- ^ Title = Hosea, Joel, and Amos | Author = Bruce C. Birch | Publisher = Westminster John Knox Press Date = 1 Jan 1997 pg = 33, pg = 56

- ^ Aubet, Maria E., 1987, 910 "The Phoenicians and the West", (Cambridge University Press, New York) p.9

- ^ a b Tubb, Jonathan "The Canaanites" (British Museum Press)

- ^ abstract, K. L. Noll (2007) "Canaanite Religion", Religion Compass 1 (1), 61–92 doi:10.1111/j.1749-8171.2006.00010.x

- ^ Moscati, Sabatino. The Face of the Ancient Orient, 2001,

- ^ Richard, Suzanne Near Eastern archaeology: a reader, Eisenbrauns illustrated edition (1 Aug 2004) ISBN 978-1-57506-083-5, p. 343

- ^ Schaeffer, Claude F. A. (1936). "The Cuneiform Texts of Ras Shamra~Ugarit" (PDF). London: Oxford University Press. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-09-20.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Olmo Lete, Gregorio del (1999), "Canaanite religion: According to the liturgical texts of Ugarit" (CDL)

- ^ Hillers D.R. (1985)"Analyzing the Abominable: Our Understanding of Canaanite Religion" (The Jewish quarterly review, 1985)

- ^ The Encyclopedia of Religion - Mcmillan Library Ref. - Page 42

Bibliography

- Moscatti, Sabatino (1968), "The World of the Phoenicians" (Phoenix Giant)

- Ribichini, Sergio "Beliefs and Religious Life" in Maoscati Sabatino (1997), "The Phoenicians" (Rissoli)

- van der Toorn, Karel (1995). Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible. New York: E.J. Brill. ISBN 0-8028-2491-9.

- Bibliography of Canaanite & Phoenician Studies