Assault on Precinct 13 (1976 film)

This article currently links to a large number of disambiguation pages (or back to itself). (December 2012) |

- For the 2005 remake, see Assault on Precinct 13 (2005 film)

| Assault on Precinct 13 | |

|---|---|

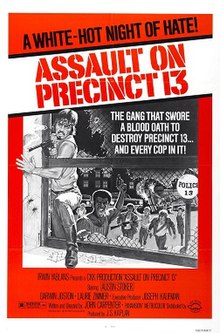

Original theatrical promotional poster, 2nd version[1] | |

| Directed by | John Carpenter |

| Written by | John Carpenter |

| Produced by | J. S. Kaplan |

| Starring | Austin Stoker, Darwin Joston, Laurie Zimmer, Nancy Kyes |

| Cinematography | Douglas Knapp |

| Edited by | John T. Chance |

| Music by | John Carpenter |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Turtle Releasing (US) Miracle Films (UK)

|

Release date | November 10, 1976 |

Running time | 91 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | US$100,000 |

| Box office | $41,000,000 |

Assault on Precinct 13 is a 1976 American action-thriller film written and directed by John Carpenter. It stars Austin Stoker as a police officer who defends a defunct precinct against an attack by a relentless criminal gang, along with Darwin Joston as a convicted murderer who helps him. Laurie Zimmer and Tony Burton co-star as other defenders of the precinct.

Writer / director Carpenter was approached by J. Stein Kaplan to make a low-budget exploitation film under $100,000 but with total creative control. Carpenter wrote The Anderson Alamo, inspired by the Howard Hawks Western film Rio Bravo and the George A. Romero horror film Night of the Living Dead. Shot in winter of 1975, production went smoothly and finished on time and on budget. Despite controversy with the MPAA over the explicitly violent and infamous "ice cream" scene, the film received an R rating and opened in the United States on November 10, 1976.

Assault was met with mixed reviews and unimpressive box-office returns in the United States. However when the film premiered in the 1977 London Film Festival, it received an ecstatic review by programmer Ken Wlaschin that led to critical and popular acclaim throughout Europe. It gained a considerable cult following and was later re-evaluated as one of the best action films of its era and of Carpenter's career. A remake appeared in 2005, directed by Jean-François Richet and starring Ethan Hawke and Laurence Fishburne.

Plot

The story takes place on a Saturday day and night in Anderson, a crime-infested ghetto in South Central Los Angeles. Members of a local gang, called 'Street Thunder', have recently stolen a large number of automatic rifles and pistols. The film begins the night before, as a team of heavily armed LAPD officers ambush and kill six members of the gang. In the morning, the gang's four warlords swear a blood oath of revenge, known as a "Cholo", against the police and the citizens of Los Angeles.

During the day, three sequences of events occur in parallel in and around Anderson: First, Lieutenant Ethan Bishop (Austin Stoker), a newly promoted CHP officer, is assigned to command the old Anderson police precinct during the last few hours before it is permanently closed. The station is manned by a skeleton staff composed of one officer, Captain Chaney (Brandon), and the station's two secretaries, Leigh (Zimmer) and Julie (Nancy Loomis).

Across town, two of the Street Thunder warlords with two other gang members drive around the neighborhood looking for people to kill. One of the warlords, shoots and kills a little girl and the driver of an ice-cream truck. The girl's father, Lawson, pursues and kills the hoodlum, whose fellow gang members chase the man into the Anderson precinct. In shock, he is unable to communicate to the officers what has happened to him.

In the third part, a prison bus commanded by Starker (Charles Cyphers) stops at the station to find medical help for one of the three prisoners being transported to Death Row at the state prison. The prisoners are Napoleon Wilson (Joston), a convicted violent killer on his way to Death Row, Wells (Burton), and Caudell, who is sick.

As the prisoners are put into jail cells, the telephone lines go dead, and when Starker prepares to put the prisoners back on the bus, the gang opens fire on the precinct, using weapons fitted with silencers. In seconds, they kill Chaney, the bus driver, Caudell, Starker, and the two officers along with Starker. Bishop unchains Wilson from Starker's body and puts Wilson and Wells back into the cells.

When the hoodlums cut the station's electricity and begin a second wave of shooting, Bishop sends Leigh to release Wells and Wilson, and they help Bishop and Leigh defend the station. Julie is killed in the firefight, and Wells is killed after being chosen to sneak out of the precinct through the sewer line.

Meanwhile, the gang members remove all evidence of the skirmish in order to avoid attracting outside attention. Bishop hopes that someone has heard the unsilenced police weapons firing, but the neighborhood is too sparsely populated for nearby residents to pinpoint the location of the noise.

As the gang rallies for a third assault, Wilson, Leigh, and Bishop retreat to the basement, taking the still-catatonic Lawson with them. The gang then storms the building in an all-out final assault and confront the survivors in the basement. Bishop shoots a tank full of acetylene gas, which explodes violently, killing the all hoodlums in the basement.

Finally, two police officers in a cruiser radio for backup after discovering the dead body of a telephone repairman hanging from a pole near the police station. When more police officers arrive and secure the station, the surviving gang members retreat. Venturing down into the basement, the police officers find dozens of dead and badly burned gang members srewn in the hallway, and the only survivors are Bishop, Leigh, Wilson, and the comatose Lawson. . Bishop asks Wilson to walk out of the station with him, rather than be led away in chains.

Cast

- Austin Stoker as Ethan Bishop

- Darwin Joston as Napoleon Wilson

- Laurie Zimmer as Leigh. According to Carpenter, Zimmer "hated herself" after seeing her performance in the dailies while he thought she did a great job.

- Martin West as Lawson

- Tony Burton as Wells

- Charles Cyphers as Starker

- Nancy Kyes as Julie

- Henry Brandon as Chaney

- Kim Richards as Kathy Lawson

- Peter Bruni as Ice Cream Man

- John J. Fox as Warden

- Frank Doubleday as White Warlord. Doubleday said to director Carpenter during the shoot: "Usually I play a man with a gun. This time I'm going to play a man who is a gun."[2]

- Marc Ross as Patrolman Tramer

- Alan Koss as Patrolman Baxter

- John Carpenter as Gang member

Production

Following the release of Dark Star, Assault was supposed to be one of two ultra-low-budget films written by John Carpenter, to be directed by Carpenter and financed by J. Stein Kaplan and Joseph Kaufman.[3] The second script was entitled Eyes.[4] After reviewing the first draft of Assault[3] and following the subsequent sale of the script Eyes to Barbra Streisand and Jon Peters, later renamed Eyes of Laura Mars,[4] Kaplan[disambiguation needed] and Kaufman concentrated on just Assault.[3] "J. Stein Kaplan was a friend of mine from USC," replied Carpenter. "He knew Joseph Kaufman from his days in Philadelphia … Basically their fathers were funding Assault on Precinct 13".[4] The two families of the producers formed the CKK corporation to finance the film.[4][5]: 1 [6]

Screenplay

Carpenter had hoped to make a Howard Hawks style western like El Dorado or Rio Lobo, but when the $100,000 budget prohibited it, Carpenter refashioned the basic scenario of Rio Bravo into a modern setting.[2][5]: 2 [6] Carpenter employed the John T. Chance pseudonym for his original version of script, entitled The Anderson Alamo, but he used his own name for the writing credit on the completed film.[5]: 3 The script was written in eight days.[7] Carpenter joked, "The script came together fast, some would say too fast."[8]

Carpenter's script makes many allusions to film history and inspirations for this film. There are many references to the films of Howard Hawks. For example, the character of Leigh, played by Laurie Zimmer, was a reference to Rio Bravo scribe Leigh Brackett.[9] The running gag of having Napoleon Wilson constantly ask Got a smoke ? was inspired by the cigarette gags used in many of Howard Hawks's westerns.[2] There are also subtle references to directors Sergio Leone and Alfred Hitchcock.[2] The day and time titles were used to make the film feel more like a documentary.[2][5]: 5&10

Pre - Production

Assault underwent several months of pre-production.[5]: 44 Carpenter assembled a main cast that consisted mostly of experienced but relatively obscure actors. The two leads were Austin Stoker, who had appeared previously in Battle for the Planet of the Apes and Sheba, Baby, and Darwin Joston, who had worked primarily in television and was also Carpenter's next-door neighbor.[8] After an open casting call, Carpenter added Charles Cyphers and Nancy Loomis to the cast.[6]

Behind the scenes, Carpenter worked with cinematographer Douglas Knapp (a fellow USC student),[2] art director Tommy Lee Wallace, sound mixer Bill Varney[10] and property master Craig Stearns.[6] "I hardly knew what the job required," replied Wallace, "but he believed in me, and, of course my price was right. It was typical of John during those lean days. He made the very best of whatever talent and facilities he had around him."[11] Carpenter drew storyboards for key sequences, including the "ice cream truck" sequence, the death of the white warlord, Napoleon Wilson struggling to get the keys of the guard after the siege starts, and the failed escape by prisoner Wells.[5]: 13 [12]

Principal Photography

Assault started in November 1975 and was shot in only 20 days, including Thanksgiving, on a budget of $100,000.[2][5]: 43 [6][a 1] The film was shot on 35mm Panavision in a 2.35:1 anamorphic aspect ratio with Metrocolor film,[2][14] Carpenter's first experience with Panavision cameras and lenses.[2] Carpenter has referred to this film as the most fun he has ever had directing.[15]

Two weeks of shooting indoors were followed by two weeks on-location.[5]: 70 The interiors of the police station were shot on the now-defunct Producers Studios set while the exterior shots and jail cells were from the old Venice police station.[5]: 87 [8] The bus traveling to Sonora was shot on a closed section of the Los Angeles freeway system, with cast and crew having lunch on the freeway.[5]: 77–86 Carpenter has said that the trick with shooting a low-budget film is to shoot as little footage as possible and extend the scenes for as long as one can.[2]

The first scene, in which several gang members of Street Thunder are gunned down by cops, was shot at USC. The gang members were USC students who, Carpenter added, had a lot of fun finding ways of dying while spilling blood over themselves.[2]

"The first night I saw dailies," replied art director Wallace, "projected on a bedsheet in the producer's ratty apartment… My jaw dropped and I sat up so straight I cast a shadow with my head. This looked like a zillion dollars. This looked like a real movie."[16]

Post - Production

Carpenter edited the film using the pseudonym John T. Chance, the name of John Wayne's character in Rio Bravo. Debra Hill acted as an uncredited assistant editor.[5]: 49 According to Carpenter, the editing process was very bare bones. One mistake Carpenter was not proud of was one shot "cut out of frame," which means the cut is made within the frame so a viewer can see it. Assault was shot on Panavision, which takes up the entire negative, and edited on Moviola, which cannot show the whole image, so if a cut was made improperly (i.e., frame line not lined up properly) then one would cut a half of a sprocket into the film and "cut out of frame," as happened to Carpenter. In the end, it did not matter because he said "It was so dark no one could see it, thank God!"[8]

Tommy Lee Wallace, the film's art director, spoke admirably about Carpenter during post. "[Carpenter] asked if I could cut sound effects. The answer, of course was 'Sure!' Once again, here I was, a perfectly green recruit, yet John made a leap of faith … he further insisted we get the best processing money could, which at that time was the legendary MGM color labs. Finally, he insisted we get the best postproduction sound money could buy, which was Samuel Goldwin Sound, another legend. The expense for this unorthodox apporach ate up a huge amount of the budget. The production manager fumed that we were exploiting people to pay for processing— and it was true."[16]

Distribution

Although the film's title is Assault on Precinct 13, the action mainly takes place in a police station referred to as Precinct 9, Division 13, by Bishop's staff sergeant over the radio. The film's distributor was responsible for the misnomer. Carpenter originally called the film The Anderson Alamo[5] before briefly changing the title to The Siege to shop to distributors.[3][a 2] The film was acquired by Irwin Yablans.[3] During post-production, however, the distributor rejected Carpenter's title in favor of the film's present name. The moniker "Precinct 13" was used in order to give the new title a more ominous tone.[5] When the film became popular in Britain, Michael Myers of Miracle Films purchased the British theatrical distribution rights.[13]

The film was released in Germany on September 3, 1979 under the title Das Ende, or The End.[5]: 168 [17]

The most infamous scene in the movie occurs when a gang member, without hesitation, shoots and kills a little girl standing near an ice-cream truck. The MPAA, headed by Richard Heffner at the time, threatened to give the film an X rating if the scene was not cut.[18][19] Following the advice of his distributor, Carpenter gave the appearance of complying by cutting the scene from the copy he gave to the MPAA, but he distributed the film with the "ice cream truck" scene intact, a common practice among low-budget films.[8][19] Carpenter regrets shooting the ice cream scene in such an explicit fashion: "…it was pretty horrible at the time … I don’t think I’d do it again but I was young and stupid."[20]

The film eventually received an R rating[14] and has a running time of 91 minutes.[a 3]

Reception

Initial Release And Critical Revision

Assault was first released in Los Angeles at the State Theater on November 10, 1976 to mixed critical reviews and unimpressive box office earnings.[13][21] Whitney Wiliams of Variety wrote, "Some exciting action in the second half packs enough interest to keep this entry alive for the violence market... John Carpenter's direction of his screenplay, after a pokey opening half, is responsible for the realistic movement."[14] Dan O'Bannon, Carpenter's co-writer on Dark Star, attended the Los Angeles premiere. At this point in their professional relationship, O'Bannon was jealous of Carpenter's success and reluctantly attended the premiere. O'Bannon was disgusted by the film and told Carpenter so. According to author Jason Zinoman, O'Bannon saw a reflection of the coolness that Carpenter displayed toward him in the film's casual disregard for the humanity of its characters. It reminded him of how easily their friendship had been discarded. "His disdain for human beings would be serviced if he could make a film without people in it," replied O'Bannon.[22]

The film opened at the Cannes Film Festival on May 1977 where it received favorable notices from some of the British critics.[13] "Carpenter at Cannes wiped us off the face of the earth with Precinct 13" replied director George A. Romero, who was at the festival with his film Martin. "Right from the scene when the little girl gets blown away, I was blown away."[18] As a result, Linda Myles booked the film for the Edinburgh Film Festival in August 1977.[13] However, it wasn't until the film was screened at the 21st London Film Festival on December 1, 1977 that the film got a major critical boost.[5]: 153 [23] Ken Wlaschin described the film in the London Film Festival brochure:

"John Carpenter, whose small-budget science-fiction epic Dark Star was widely acclaimed, has turned his inventive imagination to the thriller for his first solo directional effort. The result, even without taking into consideration his tiny budget and cast of unknowns is astonishing. Assault on Precinct 13 is one of the most powerful and exciting crime thrillers from a new director in a long time. It grabs hold of the audience and simply doesn't let go as it builds to a crescendo of irrational violence that reflects only too well our fears of unmotivated attack... It is a frightening look at the crumbling of rational ideas of law and order under an irresistible attack by the forces of irrationality and death."[23]

Wlaschin found Assault to be the best film of the London Film Festival and included it in his "Action Cinema" section of that festival.[13][23] It became one of the festival's best-received films, garnering tremendous critical and popular acclaim.[5]: 156 According to Derek Malcolm of the Guardian, the applause was "deafening".[21] Carpenter was delighted by the new praise.[13]

The overwhelmingly positive British response to the film led to its critical and commercial success throughout Europe. Derek Malcolm of Cosmopolitan wrote, "[The film] is fast becoming one of the cult movies of the year ... The great virtue of the film is the way it grabs hold of its audience and simply refuses to let go. It exploits all our fears of irrational violence and unmotivated attack, and at the same time manages to laugh at itself without spoiling the tension - a very considerable feat. Carpenter, who is clearly a director with places to go, has succeeded in making a comedy that scares the pants off us. And don't think you're laughing at it. As a matter of fact, it's laughing at you."[24][a 4] Malcolm later wrote that he held some reservations about the film: "I don't feel like going on and on about the movie, partly because I think it is in grave danger of being oversold anyway, and partly because it isn't much more to me than tremendous fun".[21] The film broke one house record in the UK and was named one of the best films of the year by critics and moviegoers.[5]: 162

Subsequently, the film underwent a reassessment by American critics and audiences, and it is now generally considered one of the best action films of the 1970s. When playing at the Chicago International Film Festival, the film was described in the program notes as, "...a nightmarish poem on which plays on our fears of irrational and uncontrolled violence."[25] Carpenter has said that the British audiences immediately understood and enjoyed the film's similarities to American westerns, whereas American audiences were too familiar with the western genre to fully appreciate the movie at first.[8][13][15]

Critical Reception

"Lean, taut and compellingly gritty, John Carpenter's loose update of Rio Bravo ranks as a cult action classic and one of the filmmaker's best."

-Rotten Tomatoes' consensus for Assault.[26]

Assault has received nearly unanimous praise from critics in the years since its release, emphasizing John Carpenter's resourceful abilities as director, writer, editor and music composer, Douglas Knapp's stylish cinematography as well as exceptional acting from Austin Stoker, Darwin Joston, Laurie Zimmer and Tony Burton. On August 18, 1979, Vincent Canby of The New York Times wrote, "[Assault] is a much more complex film than Mr. Carpenter's 'Halloween,' though it's not really about anything more complicated than a scare down the spine. A lot of its eerie power comes from the kind of unexplained, almost supernatural events one expects to find in a horror movie but not in a melodrama of this sort … If the movie is really about anything at all, it's about methods of urban warfare and defense. Mr. Carpenter is an extremely resourceful director whose ability to construct films entirely out of action and movement suggests that he may one day be a director to rank with Don Siegel."[27] In April 1980, Jeffrey Wells of Films In Review wrote, "Skillfully paced and edited, Assault was rich with Hawksian dialogue and humor, especially in the clever caricature of the classic 'Hawks woman' by Laurie Zimmer."[28] In 1986 Tom Allen and Andrew Sarris of the Village Voice described the film as "one of the most stylishly kinetic independent films of the 1970s."[29] In May 1988, Alan Jones of Starburst wrote, "Bravura remake of Rio Bravo."[30] In November 1996, Dave Golder of SFX magazine hailed the film as, "A superb, bloody thriller about a siege in an abandoned L.A. cop station."[31] In his book The Horror Films of the 1970s, John Kenneth Muir gave the film three and a half stars, calling it "a lean, mean exciting horror motion picture... a movie of ingenuity, cunning and thrills."[32] Mick Martin & Marsha Porter of the Video Movie Guide gave the film four and a half stars out of five, writing, "…John Carpenter's riveting movie about a nearly deserted L.A. police station that finds itself under siege by a youth gang. It's a modern day version of Howard Hawks' Rio Bravo, with exceptional performances by the entire cast."[33] In 2003 Dalton Ross of Entertainment Weekly described Assault as "a tight, tense thriller … Carpenter's eerie score and Douglas Knapp's stylish cinematography give this low-budget shoot-out all the weight of an urban Rio Bravo."[34] Leonard Maltin also gave the film three and a half stars out of four: "A nearly deserted L.A. police station finds itself under a state of siege by a youth gang in this riveting thriller, a modern-day paraphrase of Howard Hawks' Rio Bravo. Writer/director Carpenter also did the eerie music score for this knockout."[35]

Despite the universal acclaim, Assault is not without criticisms and detractors. Tim Pulleine of the Guardian described the film as superficial despite successfully meeting the requirements of the genre.[36] Brian Lindsey of Eccentric Cinema gave the film 6 out of a scale of 10, saying the film "isn't believable for a second — yet this doesn't stop it from being a fun little B picture in the best drive-in tradition."[37]

As of June 3, 2012, Assault currently has a 97% fresh rating on Rotten Tomatoes,[26] Carpenter's highest rated film as writer/director on the website.[38] The RT consensus is: "Lean, taut and compellingly gritty, John Carpenter's loose update of Rio Bravo ranks as a cult action classic and one of the filmmaker's best."[26]

Awards

John Carpenter won the 1978 annual British Film Institute award for the "originality and achievement of his first two films", Dark Star and Assault, at the 1977 London Film Festival.[39][40]

Legacy

Assault on Precinct 13 is now considered by many to be one of the greatest and most underrated action films of the 1970s as well as one of the best, if not the best, films in John Carpenter's career.[26][42] In the July 1999 issue, Premiere put Assault on its list of 50 "Lost and Profound" unsung film classics, writing:

"A trim, grim, vicious, and incredibly effective action movie with no cut comic-relief bit players, no winks at the audience, and no stars. Just a powder keg of a premise (lifted in part from Howard Hawks's Rio Bravo), in which a quasi-terrorist group's killing spree culminates in the action described in the title. Carpenter's mastery of wide-screen and almost uncanny talent at crafting suspense and action sequences make Assault such a nerve-racking experience that you may have to reupholster your easy chair after watching it at home."[43]

In 1988 Alan Jones of Starburst said Assault is "arguably still the best film [Carpenter] ever made."[30] In 2000 John Kenneth Muir placed the film at #3 on his rated list of John Carpenter's filmography, behind The Thing and Halloween.[44] In October 2007, Noel Murray and Scott Tobias of The A.V. Club also ranked Assault at #3 of John Carpenter's best films ("The Essentials"), saying, "The first John Carpenter film that really feels like a John Carpenter film, this homage to Howard Hawks Westerns suggests a path that Carpenter’s career might’ve taken if Halloween hadn’t become such a hit. Carpenter’s made many different kinds of movies over the course of his long career, but he hasn’t gotten to return often enough to terse tales of gun-toting heroes and villains."[45] In his fifth edition of The New Biographical Dictionary of Film in 2010, film historian David Thomson described Assault as "a Hawksian set of a police station besieged by hoodlums - economical, tense, beautiful and highly arousing. It fulfills all Carpenter's ambitions for gripping the audience emotionally and never letting go."[46] Writers Michelle Le Blanc and Colin Odell have written of the film: "[Assault] looks as fresh as the day it was first screened; its violence still shocking, its soundtrack still effective and both the dialogue and its delivery are top notch, all in a film whose $100,000 budget wouldn't satisfy the catering demands of the average Hollywood picture. This is because there is an overriding vision, a consistency to Carpenter's work that rewards repeat viewing and presents a single unifying world view."[47]

Film director Edgar Wright and actor Simon Pegg are big fans of Assault. "You wouldn't really call it an action film," claims Pegg, "because it was pre- the evolution of that kind of film. And yet it is kind of an action film in a way." "It's very much his [Carpenter's] kind of urban western", adds Wright, "in the way it is staging Rio Bravo set up in downtown 70s LA... And the other thing is, for a low budget film particularly, it looks great."[48] On October 2011, artist Tyler Stout premiered his mondo-style poster of Assault.[41] Stout's poster would be later serve as the cover on the Region B Blu-ray of Assault.[49]

Assault has influenced a number of action films that came after, setting the rules for the genre that would continue with films like Die Hard and The Matrix.[48][50]

As a result of this film, John Carpenter would go on to work with producer Irwin Yablans on Halloween, the most successful film of Carpenter's career. Due to the success of Assault in London, Carpenter named the Shape in Halloween after Michael Myers of Miracle Films, the British distributor for Assault, as a sort of campy tribute. Myers's son Martin considered the tribute as a "tremendous honor" and "a lasting memorial to his late father".[51] Donald Pleasence would go on to star in Carpenter's Halloween because his daughters were big fans of Assault.[52] Debra Hill, the film's script supervisor, would go on to produce Carpenter's future features and become his girlfriend.[6]

In 2002, the film inspired Florent Emilio Siri's 2002 quasi-remake The Nest,[53] and three years later Assault was remade by director Jean-François Richet and starring Ethan Hawke and Laurence Fishburne.[54] The Richet remake has been praised by some as an expertly made B-movie, and dismissed by others as formulaic,[55] with many critics preferring the original Assault to the remake.[56][a 5]

Analysis

Inspirations for Assault

Critics and commentators have often described Assault as a cross between Howard Hawks's Rio Bravo and George A. Romero's Night of the Living Dead.[37][56][57] Carpenter acknowledges the influence of both films.[2][8]

In his 2000 book The Films of John Carpenter, John Kenneth Muir deconstructs Carpenter's use of Rio Bravo as a template for Assault: "Although [the film's] premise may sound like typical 1970s picture, it was quintessential Carpenter in execution — which meant it was really quintessential Howard Hawks. Of primary importance was not the bloodshed or action, but rather the developing friendship and respect in evidence between the white convict Napoleon Wilson and black cop Lt. Bishop … also important in [Assault]'s homage to director Hawks was the unforgettable presence of actress Laurie Zimmer as a prototypical 'Hawksian Woman,' i.e., a female who gives as good as she gets and is both tough and feminine at the same time."[9]

Carpenter's directorial trademarks

As with most of Carpenter's antagonists, Street Thunder is portrayed as a force that possesses mysterious origins and almost supernatural qualities. "Rather than going for any particular type of gang," replied Carpenter, "I decided to include everybody."[2] The gang members are not humanized and are instead represented as though they were zombies or ghouls—they are given almost no dialogue, and their movements are stylized, with a slow, deliberate, relentless quality. Carpenter has acknowledged the influence of George A. Romero's Night of the Living Dead on his portrayal of the gang.[2][8]

Assault was shot in in 2.35:1 anamorphic Panavision widescreen, Carpenter's first use of the format which he would use on all of his feature films.[58][a 6] "I just love Panavision," replied Carpenter. "It's a cinematic ratio."[59]

Assault also marks the first time Carpenter's name would precede the title, e.g., John Carpenter's Assault on Precinct 13, which he would do on every subsequent feature film.[60]

Soundtrack

| Untitled | |

|---|---|

One of the film's distinctive features is its score, written in three days by John Carpenter[8] and performed by Carpenter and Tommy Lee Wallace.[5]: 192 Carpenter, assisted by Dan Wyman, had several banks of synthesizers that would each have to be reset when another sound had to be created, taking a great deal of time.[2][9] "When I did my original themes for [Assault] … it was done with very old technology," replied Carpenter. "It was very difficult to get the sounds, and it took very long to get something simple."[61] Carpenter made roughly three to five separate pieces of music and edited them to the film as appropriate.[8]

The main title theme, partially inspired by both Lalo Schifrin's score to Dirty Harry and Led Zeppelin's "Immigrant Song",[62] is composed of a pop synthesizer riff with a drum machine underneath that "builds only in texture, but not thematically," according to David Burnand and Miguel Mera. A held, high synthesizer note, with no other changes except inner frequency modulations, becomes the musical motif of the gang members, and reoccurs during certain violent acts in the film. In the film, synthesizers and drum machines represent the city and the gang.[63][64]

Carpenter also uses a plaintive electric piano theme when Lt. Bishop first enters the abandoned precinct. It reoccurs in the film during the quiet moments of the siege, becoming in effect a musical articulation of rhythm of the siege itself.[65] Bishop is heard whistling the tune of this particular theme at the beginning and end of the film, making the electric piano theme "a non-diegetic realization of a diegetic source."[63] Burnand and Mera have noted that "there is some attempt to show the common denominators of human behavior regardless of 'tribal' affiliations, and there is a clear attempt to represent this through simple musical devices."[66]

Many film critics who praised the film also praised the musical score by Carpenter. As John Kenneth Muir noted, "Carpenter wrote the riveting musical score for Assault… The final result was a unique, synthetic sound that is still quite catchy, even after 20 years … Delightfully, it even serves as a counterpoint in one important scene."[9][67] Dave Goldner of SFX wrote that Assault had "one of the most catchy theme tunes in film history."[31] In early 2004, Piers Martin of NME wrote that Carpenter's minimalist synthesizer score accounted for much of the film's tense and menacing atmosphere and its "impact, 27 years on, is still being felt."[62]

Beyond its use in the film, the score is often cited as an influence on various electronic and hip hop artists with its main title theme being sampled by artists including Afrika Bambaataa, Tricky, Dead Prez and Bomb the Bass.[5]: 192 [50][68] The main theme was reworked in 1986 as an Italo-disco 12"[69] and more famously as the 1990 UK-charting rave-song Hardcore Uproar.[70]

Despite this influence, except for a few compilation appearances,[5]: 193–195 the film's score remained available only in bootleg form until 2003 when it was given an official release through the French label, Record Makers.[50]

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Assault On Precinct 13 (Main Title)" | |

| 2. | "Napoleon Wilson" | |

| 3. | "Street Thunder" | |

| 4. | "Precinct 9 - Division 13" | |

| 5. | "Targets / Ice Cream Man On Edge" | |

| 6. | "Wrong Flavour" | |

| 7. | "Emergency Stop" | |

| 8. | "Lawson's Revenge" | |

| 9. | "Sanctuary" | |

| 10. | "Second Wave" | |

| 11. | "The Windows!" | |

| 12. | "Julie" | |

| 13. | "Well's Flight" | |

| 14. | "To The Basement" | |

| 15. | "Walking Out" | |

| 16. | "Assault On Precinct 13" |

Home video releases

Assault was released on VHS by Media Home Entertainment in 1978[71] and on laserdisc by Image Entertainment on March 12, 1997.[72] The '97 laserdisc came with commentary by John Carpenter, an isolated music score track and the original theatrical trailer.[72]

The film was one of the first films to be released on the DVD medium on November 25, 1997, also by Image Entertainment.[73][74] On March 11, 2003, Image Entertainment released in new widescreen "Special Edition" DVD of the film.[75] Dalton Ross of Entertainment Weekly gave this 2003 DVD release a B+.[34] Brian Lindsay of Eccentric Cinema gave the film's 2003 DVD release a 10 out of 10, the website's highest rating.[37] Special features of the 2003 DVD release[37][73] include:

- Film shown in anamorphic widescreen (2.35:1) with monaural Dolby Digital 2.0 audio.

- Q & A interview session with writer/director John Carpenter and actor Austin Stoker at American Cinematheque's 2002 John Carpenter retrospective (23 minutes)

- Original theatrical trailer

- 2 radio spots

- Behind-the-scenes and lobby card stills gallery (16 minutes)

- Full-length audio commentary by writer/director Carpenter taken from a 1997 laserdisc release[37][72][73]

- Isolated music score, also taken from the 1997 laserdisc release[72]

The film was later released on UMD video for the PlayStation Portable in July 26, 2005[76] and in a "Restored Collector's Edition" for both DVD and Blu-ray Disc in 2008 and 2009, respectively. Both releases have all of the special features found on the 2003 "Special Edition" DVD.[77][78]

See also

References

Annotations

- ^ Variety incorrectly reported in 1977 that the film cost $200,000.[13]

- ^ The Siege was later used as the title of another very controversial film, a 1998 drama about terrorist attacks in the U.S. starring Bruce Willis and Denzel Washington.

- ^ The full running time of the film's 2003 DVD release is 90 minutes and 55 seconds.

- ^ Derek Malcolm is quoted on two of the British Assault poster as calling it "The Cult Film of the Year".[5]

- ^ Leonard Maltin gave two stars out of four for the 2005 remake, describing it as, "Violent remake of lean, mean John Carpenter B movie adds a variety of plot complications—and with each one, another layer of disbelief. Well crafted but laughable at times."[35]

- ^ The only exception to this rule was his 2010 film The Ward which was shot flat then cropped into a 2.35:1 aspect ratio.

Notes

- ^ "Assault on Precinct 13 - Poster #2". IMP Awards. Retrieved 2010-08-29.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Carpenter, John (writer/director). (2003). Audio Commentary on Assault on Precinct 13 by John Carpenter. [DVD]. Image Entertainment.

- ^ a b c d e Boulenger 2003, p. 85.

- ^ a b c d Boulenger 2003, p. 89.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Kaufman, Joseph[[{{subst:DATE}}|{{subst:DATE}}]] [disambiguation needed] (2003). Production Gallery [DVD]. Image Entertainment.

- ^ a b c d e f Muir 2000, p. 10.

- ^ Boulenger 2003, p. 28.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Q & A session with John Carpenter and Austin Stoker at American Cinematheque's 2002 John Carpenter retrospective, in the 2003 special edition Region 1 DVD of Assault on Precinct 13.

- ^ a b c d Muir 2000, p. 11.

- ^ Lentz, Harris M. (May 3, 2012). Obituaries in the Performing Arts, 2011 (Paperback ed.). Mcfarland. p. 358. ISBN 978-0786469949.

- ^ Boulenger 2003, p. 16.

- ^ "Storyboards - Assault on Precinct 13". The Official John Carpenter. Retrieved 2012-06-03.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "John Carpenter Surprised by "Precinct" Praise". Variety. p. 13. December 14, 1977.

- ^ a b c Williams, Whitney (November 17, 1976). "Assault on Precinct 13". Variety. p. 19.

- ^ a b Muir 2000, p. 12.

- ^ a b Boulenger 2003, p. 17.

- ^ "Assault - Anschlag bei Nacht" (in German). zelluloid.de. Retrieved 2012-08-05. "09.03.1979 Kinostart Deutschland".

- ^ a b Zinoman 2011, p. 122.

- ^ a b Zinoman 2011, p. 123.

- ^ "John Carpenter (Director) - Interview". Sci-fi Online. August 10, 2008. Retrieved 2012-07-22.

- ^ a b c Malcolm, Derek (March 9, 1978). "Cinema" Guardian. Retrieved 2012-08-21.

- ^ Zinoman 2011, p. 120.

- ^ a b c Wlaschin, Ken (December 1977). "Assault on Precinct 13". 21st London Film Festival [Brochure]. p. 58.

- ^ Malcolm, Derek (February 1978). "Cosmo sees the films". Cosmopolitan Magazine.

- ^ "Assault on Precinct 13". Chicago International Film Festival [Program]. p. 34. 1978. Retrieved 2012-08-25.

- ^ a b c d "Assault on Precinct 13 (1976)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 2012-06-03.

- ^ Vincent Canby (August 18, 1979). "A Late Rossellini And an Early Carpenter". The New York Times. Retrieved 2012-07-15.

- ^ Wells, Jeffrey (April 1980). "New Fright Master John Carpenter". Films In Review. p. 218.

- ^ Allen, Tom; Sarris, Andrew (June 3, 1986). "Assault on Precinct 13". Village Voice.

- ^ a b Jones, Alan (May 1988). "John Carpenter — Prince of Darkness". Starburst. p. 8.

- ^ a b Golder, Dave (November 1996). "L.A. Story". SFX. pp. 54-56.

- ^ Muir, John Kenneth (1999). "Assault on Precinct 13"

. The Horror Films of the 1970s (Hardcover ed.). New York, NY: McFarland and Company Inc. pp. 376-379. ISBN 0-7864-1249-6.

. The Horror Films of the 1970s (Hardcover ed.). New York, NY: McFarland and Company Inc. pp. 376-379. ISBN 0-7864-1249-6.

- ^ Martin, Mick; Porter, Marsha (October 2001). "Assault on Precinct 13"

. Video Movie Guide (2002 ed.). New York, NY: Ballantine Books. pp. 53-54. ISBN 0-345-42100-0.

. Video Movie Guide (2002 ed.). New York, NY: Ballantine Books. pp. 53-54. ISBN 0-345-42100-0.

- ^ a b Ross, Dalton (March 14, 2003). "Assault On Precinct 13". Entertainment Weekly (700). p. 49. Retrieved 2012-07-28. "EW Grade: B+".

- ^ a b Maltin, Leonard (August 2008). Leonard Maltin's Movie Guide (2009 ed.). New York, NY: Penquin Group. p. 64. ISBN 978-0-452-28978-9.

- ^ Pulleine, Tim (March 8, 1978). "Fire in the Streets". Guardian. Retrieved 2012-08-25.

- ^ a b c d e Lindsey, Brian (April 6, 2003). "ASSAULT ON PRECINCT 13 (1976)". Eccentric Cinema. Retrieved 2009-11-30.

- ^ "John Carpenter". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 2012-06-03.

- ^ Robinson, David (March 10, 1978). "John Carpenter proves himself a firstrate story-teller". London Times. Retrieved 2012-08-25.

- ^ Andrews, Nigel (March 10, 1978). "Cinema". Financial Times. Retrieved 2012-08-20.

- ^ a b "Assault on Precinct 13 by Tyler Stout". 411posters. November 10, 2011. Retrieved 2012-06-04.

- ^ Dixon, Wheeler Winston; Foster, Gwendolyn (March 5, 2008). A Short History of Film (First ed.). Rutgers University Press. p. 358. ISBN 978-0813542706.

- ^ Agresti, Aimee; Brown, Jennifer; Cronis, Chris; Fernandez, Jay A; Gallo, Holly; Gopalan, Nisha; Karren, Howard; Kenny, Glenn; Lewin, Alex; Matloff, Jason (July 1999). "Lost and Profound". Premiere. Hachette Filipacchi Magazines II, Inc.: New York, NY. p. 98. ISSN 0894-9263. (Reprinted at Combustible Celluloid as "Premiere - 100 Most Daring Movies & 50 Unsung Classics" from the October 1998 & July 1999 issues of Premiere). Retrieved 2010-10-13.

- ^ Muir 2000, p. 248.

- ^ Murray, Noel; Tobias, Scott (October 27, 2011). "John Carpenter | Film | Primer" The A.V. Club. Retrieved 2012-06-03.

- ^ Thomson, David (October 26, 2010). The New Biographical Dictionary of Film: Fifth Edition, Completely Updated and Expanded (Hardcover ed.). Knopf. p. 155. ISBN 978-0-307-27174-7.

- ^ Le Blanc & Odell 2011, p. 11.

- ^ a b Pegg, Simon; Wright, Edgar (hosts). The Classic Cult Film Festival: Assault On Precinct 13 [video]. 2007.

- ^ "DVD & BLU-RAY". Midnight-Media. Retrieved 2012-08-25.

- ^ a b c "Assault on Precinct 13 Soundtrack" (in French). Record Makers. Retrieved 2009-12-13.

- ^ Jones, Alan (October 17, 2005). The Rough Guide to Horror Movies. Rough Guides. p. 200. ISBN 978-1843535218.

- ^ Muir 2000, p. 13.

- ^ Wheeler, Jeremy. The Nest: Critics' Review. MSN Movies. Retrieved 2012-06-02.

- ^ "Assault on Precinct 13 (2005)". All Movie Guide. Retrieved 2012-06-02.

- ^ "Assault on Precinct 13 (2005)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 2010-08-28. "[Consensus] This remake has been praised by some as an expertly made B-movie, and dismissed by others as formulaic."

- ^ a b Corilss, Richard (January 16th, 2005). "Movies: Repeat Assault, with Vigor". Time. Retrieved 2010-08-28.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (January 19, 2005). "Assault on Precinct 13". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 2012-06-02

- ^ Conrich; Woods, 2004, p. 66.

- ^ Applebaum, R. (June 1979). "From Cult Homage to Creative Control". Films and Filming. London. p.10.

- ^ Le Blanc & Odell 2011, p. 13.

- ^ Boulenger 2003, p. 56.

- ^ a b Martin, Piers (January 10, 2004). "John Carpenter Assault on Precinct 13 Soundtrack". NME.

- ^ a b Conrich; Woods, 2004, p. 56.

- ^ Conrich; Woods, 2004, p. 57.

- ^ Conrich; Woods, 2004, p. 55.

- ^ Conrich; Woods, 2004, p. 58.

- ^ Muir 2000, p. 70.

- ^ Chang, Jeff (January 27, 2005). Can't Stop Won't Stop: A History of the Hip Hop Generation (First ed.). St. Martin's Press. p. 99. ISBN 9780312301439.

- ^ "JOHN CARPENTER - THE END" [Video]. YouTube. January 13, 2009. Retrieved 2012-06-02.

- ^ "Together - Hardcore Uproar". backtotheoldskool.co.uk. Retrieved 2012-06-02.

- ^ "Assault on Precinct 13: A White Hot Night of Hate (Meda Home Entertainment, 1978)". Amazon.com. Retrieved 2012-07-28.

- ^ a b c d "Assault On Precinct 13: Special Edition (1976) [ID2304CK]". LaserDisc Database. Retrieved 2012 -07-28.

- ^ a b c "Editor" [Anonymous] (March 10, 2003). "News and Commentary: March 2003". The DVD Journal. Retrieved 2012-07-28.

- ^ "Assault on Precinct 13 (1976) Blu-ray Movie Screenshots". CinemaSquid. Retrieved 2012-07-28. "DVD 1997-11-25"

- ^ "Assault on Precinct 13 (2003 Special Edition DVD) (1976)". Amazon.com. Retrieved 2010-10-15.

- ^ "Assault on Precinct 13 [UMD for PSP]". Amazon.com. Retrieved 2012-07-28.

- ^ "Assault on Precinct 13 (Restored Collector's Edition DVD) (1976)". Amazon.com. Retrieved 2010-10-15.

- ^ "Assault on Precinct 13 (Restored Collector's Edition Blu-ray) (1976)". Amazon.com. Retrieved 2010-10-15.

Bibliography

- Boulenger, Gilles (2003). John Carpenter: The Prince of Darkness (First US ed.). Beverly Hills, CA: Silman-James Press. ISBN 1-879505-67-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Conrich, Ian; Woods, David, eds. (2004). The Cinema of John Carpenter: The Technique of Terror. London, England: Wallflower Press. ISBN 1-904764-14-2.

- Le Blanc, Michelle; Odell, Colin (April 28, 2011). John Carpenter (Creative Essentials) (Paperback ed.). Great Britain: Kamera Books. ISBN 978-1842433386.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Muir, John Kenneth (2000). The Films of John Carpenter (Hardcover ed.). New York, NY: McFarland and Company Inc. ISBN 0-7864-0725-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Zinoman, Jason (July 7, 2011). Shock Value: How a Few Eccentric Outsiders Gave Us Nightmares, Conquered Hollywood, and Invented Modern Horror (Hardcover ed.). New York, NY: The Penguin Press. ISBN 978-1594203022.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Further reading

- Baily, K. (March 12, 1978). Sunday People.

- Barker, F. (March 9, 1978). The Evening News.

- Barkley, F. (March 12, 1978). Sunday Express.

- Bernandes, H. (1995). Armante Cinema 45 (in Spanish). p. 37.

- Bitomsky, Hartmut; Hofmann, Felix (February 2, 1979). "Assault on Precinct 13" (in German). Internationale Filmfestspiele Berlin [Program]. Retrieved 2012-08-25.

- Bordwell, David (April 10, 2006). The Way Hollywood Tells It: Story and Style in Modern Movies (First ed.). University of California Press. p. 59. ISBN 978-0520246225.

- Brien, A. (March 12, 1978). Sunday Times.

- Christie, I. (March 11, 1978). Daily Express.

- Chute, David (March 13, 1979) "Second sight: on becoming king of the Bs". Boston Phoenix. pp. 4, 12. Retrieved 2012-08-25.

- Coleman, J. (March 10, 1978). New Statesman.

- Combs, Richard (1977/8). Sight and Sound 47. pp. 1, 58-9.

- Davies, R. (March 12, 1978). Observer.

- Dignam, V. (March 10, 1978). Morning Star.

- Dixon, Wheeler Winston (August 24, 2010). A History of Horror (Paperback ed.). Rutgers University Press. pp. 130, 132 & 135. ISBN 978-0813547961.

- Divine, C. (2000). "Noir Romantics: The Urban Poetry of Assault on Precinct 13". Creative Screenwriting. pp. 5,7, 20-22.

- Gibbs, P. (March 10, 1978). Daily Telegraph.

- Gow, G. (1978). Films and Filming. pp. 5, 24, 45.

- Harmsworth, M. (March 12, 1978). "Cracker in the ghetto". Sunday Mirror.

- Hinxman, M. (March 10, 1978). Daily Mail.

- Hutchinson, T. (March 12, 1978). Daily Telegraph.

- Klein, David (December 30, 2011). If 6 Was 9 And Other Assorted Number Songs (Paperback ed.). lulu.com. p. 73. ISBN 978-1257759330.

- Maltin, Leonard (Winter 2007/2008). "Overstaying Your Welcome". DGA Quarterly. Retrieved 2012-08-04.

- Maltin, Leonard (August 12, 2008). "Post #2". Penquin.com. Retrieved 2012-08-04.

- Milne, Tom (1978). Monthly Film Bulletin 529. p. 19-20.

- Plowright, M. (September 1978). "A hoodlum siege that could happen". Glasgow Herald.

- Sigal, C. (March 18, 1978). Spectator.

- S.M. (1978). Films Illustrated.

- Thirkell, A. (March 10, 1978). "Guns in the ghetto". Daily Mirror.

- Walker, A. (March 9, 1978). Eveing Standard.

- Williams, T. (1979). "Assault on Precinct 13: The Mechanics of Repression". In Wood, Robin; Lippe, R. (eds). The American Nightmare: Essays on the Horror Film. Tornoto, Canada: Festivals of Festivals. pp. 67–73.

External links

- Assault on Precinct 13 at IMDb

- Assault on Precinct 13 at AllMovie

- Assault on Precinct 13 (1976) on the Official John Carpenter website

- Assault on Precinct 13 Trailer on YouTube

- Review on ReviewGraveyard.com

- Listen to the original soundtrack for Assault on Precinct 13

- Articles with links needing disambiguation from December 2012

- Pages with excessive dablinks from December 2012

- 1976 films

- 1970s action films

- 1970s thriller films

- American action thriller films

- American independent films

- English-language films

- Exploitation films

- Films directed by John Carpenter

- Films set in Los Angeles, California