Backergunge District

| Backergunge Bakarganj বাকেরগঞ্জ | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| District of the Bengal Presidency | |||||||||

| 1760–1947 | |||||||||

|

Flag | |||||||||

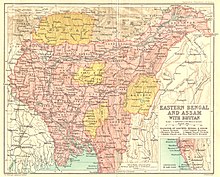

Backergunge District in a 1909 Eastern Bengal map of The Imperial Gazetteer of India | |||||||||

| Capital | Barisal | ||||||||

| Area | |||||||||

• 1901 | 11,763 km2 (4,542 sq mi) | ||||||||

| Population | |||||||||

• 1901 | 2,291,752 | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

• Establishment of the district | 1760 | ||||||||

• Partition of India | 1947 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||

| This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Backergunje". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. | |||||||||

Backergunge, Backergunje, Bakarganj, or Bakerganj was a former district of British India. It was the southernmost district of the Dacca Division. The district was located in the swampy lowlands of the vast delta of the Ganges and the Brahmaputra rivers.

Backergunge District was established in 1760 under the Bengal Presidency.[1] In 1947 the district became part of East Pakistan. The area of the former Backergunge district is now covered by the Barisal Division of Bangladesh. The current administrative division also contains a Barisal District and a Bakerganj Upazila.

Geography

Backergunge District was bound in the north by Faridpur District and in the east by the Meghna and Shahbazpur rivers.

In 1801 the Barisal subdivision was formed within the district, divided in six thanas: Barisal, Jhalakati, Nalchiti, Bakarhanj, Mehndiganj and Gaurnadi.[2]

The general aspect of the district was that of a flat even country, dotted with clusters of bamboo and arecanut palms, and intersected by a network of dark-coloured and sluggish streams. There is not a hill or hillock in the whole district, but it derives a certain picturesque beauty from its wide expanses of cultivation, and the greenness and freshness of the vegetation. This was especially true immediately after the rains, although at no time of the year does the district presented a dried-up or burnt appearance. The villages were often surrounded by groves of bamboo, arecanut palms and betel vines.[1]

The level of the country was low with numerous streams, wetlands and shallow lakes around the margins of which, long grasses, reeds and other aquatic plants grow. Towards the north-west, the country was very marshy and nothing was to be seen for miles but swamps and rice fields, with a few huts scattered here and there raised on mounds of earth. In the south of the district, along the coast of the Bay of Bengal, were the forest tracts of the Sundarbans where tigers and leopards used to live.

The main rivers of the district were the Meghna, the Arial Khan and the Haringhata or Baleswar, with their numerous tributaries. The Meghna includes the accumulated waters of the Brahmaputra and Ganges. It flows along the eastern boundary of the district in a southerly direction until it flows into the Bay of Bengal. During the latter part of its course the river expands into a large estuary containing many islands, the largest one being Dakshin Shahbazpur. The islands on the seafront are regularly exposed to devastation by cyclonic storm-waves.

The Arial Khan, a branch of the Ganges, entered the district from the north, flowing generally in a south-easterly direction until it entered the estuary of the Meghna. The main channel of the Arial Khan was about 1,500 metres (1,600 yd) in width in the dry season, and from 2,000 to 3,000 metres (2,200 to 3,300 yd) in the rains. It received a number of tributaries, sending off several offshoots, and used navigable throughout the year by local cargo boats that were often of considerable size.

The Haringhata, Baleswar, Madhumati and Garai are different local names for the same river along various parts of its course and it represent another great offshoot of the Ganges. It entered Backergunge near the north-west corner of the district, forming its western boundary, and running south with great windings in its upper reaches, until it crossed the Sundarbans, finally flowing into the Bay of Bengal forming a large and deep estuary, capable of harbouring ships of considerable size.

In the whole of its course through the district, the river used to be navigable by local boats of large tonnage, and by large seagoing ships as high up as Morrellganj, in the neighbouring district of Jessore. Among its many tributaries in Backergunge, the most important is the Kacha, navigable all the year round and flowing in a southerly direction for 30 km (19 mi) until it joined the Baleswar. Other rivers of minor importance were the Barisal, Bishkhali, Nihalganj, Khairabad, Ghagar, Kumar, etc.

All the rivers in the district were subject to tidal action from the Meghna on the north, and from the Bay of Bengal on the south, and nearly all of them are navigable at high tide by country boats of all sizes. The rise of the tide was very considerable in the estuary of the Meghna, and many of the creeks and water-courses in the island of Dakshin Shahbazpur, which are almost dry at ebb tide, contain 5.5 to 6 m (18 to 20 ft) of water at the flood. A very strong tidal bore or wave ran up the estuary of the Meghna at spring tides, and a singular sound like thunder, known as the Barisal guns, was often heard far out at sea, about the time the tidal wave was coming in.

Population

In 1901, the population was 2,291,752, showing an increase of 6% over the decade. About a 68% of the inhabitants in the region were Muslim, of which a number adhered to the Faraizis or Puritan sect. The Hindu population numbered 713,800, of which the most numerous community were the Namasudras. The Buddhist population consisted of about 7,220 Maghs who originated in Arakan and first settled in Backergunge around the year 1800.[1]

A number of small trading villages existed throughout the district, and each locality has its periodical trading fairs. Local people were mostly small land-holders and cultivated sufficient rice and other products for the support of their families.

See also

References

- ^ a b c Imperial Gazetteer of India, v. 6, p. 165.

- ^ Hunter, William Wilson, Sir, et al. (1908). Imperial Gazetteer of India, Clarendon Press, Oxford.