Balalaika

| |

| String instrument | |

|---|---|

| Classification | Plucked string instrument |

| Hornbostel–Sachs classification | 321.321 (Composite chordophone) |

| Developed | Late 18th to early 19th centuries |

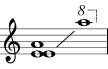

| Playing range | |

| |

| Related instruments | |

| Domra | |

| More articles or information | |

Template:Contains Cyrillic text

The balalaika (Russian: балала́йка, pronounced [bəɫɐˈɫajkə]) is a Russian stringed musical instrument with a characteristic triangular body and three strings.

The balalaika family of instruments includes instruments of various sizes, from the highest-pitched to the lowest: the piccolo balalaika, prima balalaika, secunda balalaika, alto balalaika, bass balalaika, and contrabass balalaika. The prima balalaika is the most common; the piccolo is rare. There have also been descant and tenor balalaikas, but these are considered obsolete. All have three-sided bodies; spruce, evergreen, or fir tops; and backs made of three to nine wooden sections (usually maple). They are typically strung with three strings, and the necks are fretted.

The prima balalaika, secunda and alto are played either with the fingers or a plectrum (pick), depending on the music being played, and the bass and contrabass (equipped with extension legs that rest on the floor) are played with leather plectra. The rare piccolo instrument is usually played with a pick.[1]

Etymology

The earliest mention of the term balalaika dates back to an AD 1688 Russian document.[2] The term "balabaika" was used in Ukrainian language document from XVIII century.[3] According to one theory,[specify] the term was loaned to Russian, where – in literary language – it first appeared in "Elysei", a 1771 poem by V. Maikov.

Types

The most common solo instrument is the prima, which is tuned E4-E4-A4 (thus the two lower strings are tuned to the same pitch). Sometimes the balalaika is tuned "guitar style" by folk musicians to G3-B3-D4 (mimicking the three highest strings of the Russian guitar), whereby it is easier to play for Russian guitar players, although classically trained balalaika purists avoid this tuning. It can also be tuned to E4-A4-D5, like its cousin, the domra, to make it easier for those trained on the domra to play the instrument, and still have a balalaika sound. The folk (pre-Andreev) tuning D4-F♯4-A4 was very popular, as this makes it easier to play certain riffs.[4]

The balalaika has been made the following sizes:[5]

| Name | Length | Common Tuning | (Notes) |

|---|---|---|---|

| descant | ~18"(46 cm) | E5 E5 A5 | 1 |

| piccolo | ~24" (61 cm) | B4 E5 A5 | 2 |

| prima | 26-27" (66-69 cm) | E4 E4 A4 | 3 |

| secunda | 27-29" (68-74 cm) | A3 A3 D4 | 3, 4 |

| alto | 32" (81 cm) | E3 E3 A3 | 3 |

| tenor | 36-38" (91-97 cm) | E3 A3 E4 | 1 |

| bass | 41" (104 cm) | E2 A2 D3 | 3 |

| contrabass | 51-65" (130-165 cm) | E1 A1 D2 | 3,2 |

Notes: (1) Obsolete : (2) Rare : (3) Members of the modern Balalaika Orchestra. : (4) Secundas are often the same instrument as Primas, just tuned a lower pitch range.

Factory-made six-string prima balalaikas with three sets of double courses are also common. These have three double courses similar to the stringing of the mandolin and often use a "guitar" tuning. Although they are popular (particularly in Ukraine), they are generally considered to be inferior in quality to single course instruments.

Four string alto balalaikas are also encountered and are used in the orchestra of the Piatnistky Folk Choir.

The piccolo, prima, and secunda balalaikas were originally strung with gut with the thinnest melody string made of stainless steel. Today, nylon strings are commonly used in place of gut.

Technique

An important part of balalaika technique is the use of the left thumb to fret notes on the lower string, particularly on the prima, where it is used to form chords. Traditionally, the side of the index finger of the right hand is used to sound notes on the prima, while a plectrum is used on the larger sizes. One can play the prima with a plectrum, but it is considered rather unorthodox to do so.

Because of the large size of the contrabass's strings, it is not uncommon to see players using plectrums made from a leather shoe or boot heel. The bass balalaika and contrabass balalaika rest on the ground, on a wooden or metal pin that is drilled into one of its corners.[6]

History

Possible origins of the Balalaika

The exact origins of the Balalaika are unknown.

However, it is commonly agreed that it descended from the Domra, an instrument from the Caucasus region of Russia. There is also similarity to the Kazakh Dombra, which has 2 strings, and the Mongolian Topshur.

The pre-Andreyev period

Early representations of the balalaika show it with anywhere from two to six strings, which resembles certain Central Asian instruments. Similarly, frets on earlier balalaikas were made of animal gut and tied to the neck so that they could be moved around by the player at will (as is the case with the modern saz, which allows for the playing distinctive to Turkish and Central Asian music).

The first known document mentioning the instrument dates back to 1688. A guard's logbook from the kremlin records that two commoners were stopped from playing the Balalika whilst drunk.[7] Further documents from 1700 and 1714 also mention the instrument. In the early 18th century the term appeared in Ukrainian documents, where it sounded like "Balabaika". Balalaika appeared in "Elysei", a 1771 poem by V. Maikov. In the 19th century, the balalaika evolved into a triangular instrument with a neck that was substantially shorter than that of its Asian counterparts. It was popular as a village instrument for centuries, particularly with the skomorokhs, sort of free-lance musical jesters whose tunes ridiculed the Tsar, the Russian Orthodox Church, and Russian society in general.

A popular notion is that the three sides and the strings of the balalaika represent the Holy Trinity.[citation needed] This idea, while whimsical, is quite difficult to fathom when one is confronted with the fact that at various times in Russian history, the playing of the balalaika was banned because of its use by the skomorokhi, who were generally highly irritating to both church and state. Musical instruments are not allowed in Russian Orthodox liturgy. A likelier reason for the triangular shape is given by the writer and historian Nikolai Gogol in his unfinished novel Dead Souls. He states that a balalaika was made by peasants out of a pumpkin. If you quarter a pumpkin, you are left with a balalaika shape.[improper synthesis?]

The Andreyev period

In the 1880s, Vasily Vasilievich Andreyev, who was then a professional violinist in the music salons of St Petersburg, developed what became the standardized balalaika, with the assistance of violin maker V. Ivanov. The instrument began to be used in his concert performances. A few years later, St. Petersburg craftsman Paserbsky further refined the instruments by adding a fully chromatic set of frets and also a number of balalaikas in orchestral sizes with the tunings now found in modern instruments. Andreyev patented the design and arranged numerous traditional Russian folk melodies for the orchestra. He also composed a body of concert pieces for the instrument.

Balalaika orchestra

The end result of Andreyev's labours was the establishment of an orchestral folk tradition in Tsarist Russia, which later grew into a movement within the Soviet Union. The balalaika orchestra in its full form – balalaikas, domras, gusli, bayan, kugiklas, Vladimir Shepherd's Horns, garmoshkas and several types of percussion instruments – has a distinctive sound: strangely familiar to the ear, yet decidedly not entirely Western European.

With the establishment of the Soviet system and the entrenchment of a proletarian cultural direction, the culture of the working classes (which included that of village labourers) was actively supported by the Soviet establishment. The concept of the balalaika orchestra was adopted wholeheartedly by the Soviet government as something distinctively proletarian (that is, from the working classes) and was also deemed progressive. Significant amounts of energy and time were devoted to support and foster formal study of the balalaika, from which highly skilled ensemble groups such as the Osipov State Balalaika Orchestra emerged. Balalaika virtuosi such as Boris Feoktistov and Pavel Necheporenko became stars both inside and outside the Soviet Union. The movement was so powerful that even the renowned Red Army Choir, which initially used a normal symphonic orchestra, changed its instrumentation, replacing violins, violas, and violoncellos with orchestral balalaikas and domras.

Balalaika solo

Often musicians perform solo on the balalaika. In particular, Alexey Arkhipovsky is well known for his solo performances. In particular, he was invited to play at the opening ceremony of the second semi final of the Eurovision Song Contest 2009 in Moscow because the organizers wanted to give a "more Russian appearance" to the contest.[8]

The balalaika in popular culture

Through the 20th century, interest in Russian folk instruments grew outside of Russia, likely as a result of western tours by Andeyev and other balalaika virtuosi early in the century. Orchestras of Russian folk instruments exist in many countries of western Europe, Scandinavia, USA, Canada, Australia and Japan. Some of the groups include ethnic Russians, however in recent times the growth in interest in the Balalaika by non-ethnic Russians has been considerable. A Google search on "American Balalaika Orchestras" yields over 200,000 references. Significant Balalaika associations are found in Washington, D.C.;[9] Los Angeles;[10] New York;[11] Atlanta;[12] Seattle;[13] and is dozens of smaller cities and universities.

- Ian Anderson plays balalaika on two songs from the 1969 Jethro Tull album Stand Up: "Jeffrey Goes To Leicester Square" and "Fat Man".[14]

- Wes Anderson's 2014 film The Grand Budapest Hotel (winner of the 87th Academy Awards for best Original Score)[15] employs many balalaikas in both Alexandre Desplat's original score and several sound-track recordings by the Osipov State Russian Folk Orchestra.

- Basement Jaxx's 2006 single "Take Me Back To Your Place" displays balalaikas of all sizes in the official video.[16]

- Oleg Bernov of the Russian-American rock band the Red Elvises plays a red electrified contrabass balalaika during the band's North American tours.

- Kate Bush, English singer, featured the balalaika (played by her brother Paddy Bush) in two of her Top-40 singles, "Babooshka" and "Running Up That Hill".[17]

- Episode 608 of Gilmore Girls is titled "Let Me Hear Your Balalaikas Ringing Out."

- Katzenjammer, the Norwegian all-girl pop band, uses two contrabass balalaikas, both of which have cat faces painted on the front. They are named Børge and Akerø.[18][19]

- David Lean's 1965 film Doctor Zhivago features balalaika prominently in the score and the plot.

- Roger, Hayley, and Klaus of the animated cartoon American Dad! form a balalaika trio during season 10 episode 4; Crotchwalkers.[20]

- VulgarGrad. an Australian band fronted by actor Jacek Koman, plays songs of the Russian criminal underground, and uses a contrabass balalaika.[21]

See also

References

- ^ "The Washington Balalaika Society". www.balalaika.org.

- ^ Belinskiy, Dmitry. "Balalaika". Krymskaya Pravda. Balalaika music, video.

- ^ Історичний словник українського язика Під ред. Є. Тимченка; укл.: Є. Тимченко, Є. Волошин, К. Лазаревська, Г. Петренко. — К.-Х., 1930–32. — Т. 1. — XXIV + 948 с. Зошит 1: А — Глу. — С. 52.

- ^ Micha Tcherkassky. "Balalaika.fr – Origins of balalaika". free.fr.

- ^ Ekkel, Bibs; The Complete Balalaika Book; Mel Bay Publications; Pacific, Missouri: 1997. pg. 90-92. ISBN 0-7866-2475-2

- ^ "110mb.com – Want to start a website?". 110mb.com.

- ^ "Balalaika orchestra offers glimpse of instruments, music". The Daily Progress. 28 September 2012. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- ^ Алексей Архиповский: Выступлением на "Евровидении" я недоволен! (in Russian). NEWSmusic.Ru. Retrieved 5 May 2012.

- ^ "The American Balalaika Symphony: Experience It!". absorchestra.org. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- ^ "Los Angeles Balalaika Orchestra". russianstrings.com. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- ^ "New York Russian Balalaika Orchestra". barynya.com. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- ^ "Atlanta Balalaika Society". atlantabalalaika.com. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- ^ "Washington Balalaika Society – Home". balalaika.org. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- ^ "Stand Up – Jethro Tull". jethrotull.com. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- ^ "THE 87TH ACADEMY AWARDS 2015".

- ^ Take Me Back To Your Place

- ^ Running Up That Hill

- ^ "Security Check Required". facebook.com. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- ^ Akero – Its All About The Bass – Katzenjammer. 29 September 2015. Retrieved 23 February 2016 – via YouTube.

- ^ Crotchwalkers. 11 November 2013. Retrieved 23 February 2016 – via YouTube.

- ^ "Band". Vulgargrad. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- Блок В. Оркестр русских народных инструментов. Москва, 1986.

- Имханицкий М. В. В. Андреев – Материалы и документы. Москва, 1986.

- Имханицкий М. У истоков русской народной оркестровой культуры. Москва, 1987.

- Имханицкий М. История исполнительства на русских народных инструментах. Москва, 2002.

- Пересада А. Балалайка. Москва, 1990.

- Попонов В. Оркестр хора имени Пятницкого. Москва, 1979.

- Попонов В. Русская народная инструментальная музыка. Москва, 1984.

- Вертков К. Русские народные музыкальные инструменты. Музыка, Ленинград, 1975.

External links

- (en) "Balalaika"—article by Dmitry Belinskiy from the newspaper Krymskaya Pravda. Balalaika music, video

- Russian site about Balalaika. History of balalaika, by Georgy Nefyodov

- Chord reference for Prima-Balalaika

- (rus) balalaika.org.ru: music sheets, video, forum, etc.

- An example of balalaika playing on YouTube

- (de) russische-balalaika.de – informative Website