Euphrates Region

Euphrates Region

Herêma Firatê | |

|---|---|

One of seven de facto regions of the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria | |

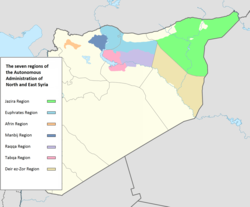

The regions of the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria, the Euphrates Region is in light blue | |

| Country | |

| Governorate | Aleppo, Raqqa |

| De facto regional government | Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria |

| Autonomy declared | January 27, 2014 |

| Administrative center | Kobanî[1] |

| Government | |

| • Co-presidents | Lemis Abdullah and Mihemed Şahin |

| Population | |

| • Estimate (2004[2]) | 322,227 |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

| Area code | +963 21 |

Euphrates Region, formerly Kobanî Canton, (Kurdish: Herêma Firatê, Arabic: إقليم الفرات, Classical Syriac: ܦܢܝܬܐ ܕܦܪܬ, romanized: Ponyotho d'Prat) is the central of three original regions of the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria, comprising Ayn al-Arab District of the Aleppo Governorate, Tell Abyad District of the Raqqa Governorate, and the westernmost tip of the Ras al-Ayn Subdistrict of the Ras al-Ayn District of Al-Hasakah Governorate. Euphrates Region unilaterally declared autonomy in January 2014 and since de facto is under direct democratic government in line with the polyethnic Constitution of Rojava.

The region has two subordinate cantons, the Kobani canton consisting of the Sarrin area (with the al-Jalabiya district subordinate to it) and the Kobani area (with the Şêran and the Qenaya Subdistricts subordinate to it), as well as the Tel Abyad canton (with the Ain Issa and Suluk Subdistricts subordinate to it).[3]

Demographics

[edit]The current population of Euphrates Region is unknown due to substantial refugee movements, but that of Kobane Canton alone before 2014 was estimated at 400,000, with an ethnic Kurdish majority.[4] Due to intense fighting at least three-quarters of the population fled across the border to Turkey in 2014;[5] however, many returned in 2015.[6]

The largest locality of the region and the only one with more than 10,000 inhabitants is according to the 2004 Syrian census, Kobanî (44,821).

History

[edit]The present Kurdish-populated area on the left bank of the Euphrates was settled by Kurdish tribes at the beginning of the 17th century.[7] In modern post-independence Syria, the Kurdish population of the region was subject to heavy-handed Arabization policies by the Damascus government.[8] In the course of the Syrian Civil War and the Rojava conflict, Syrian government forces withdrew from the area, and on 27 January 2014 an autonomous Kobanî Canton under the Constitution of Rojava was declared and institutions established.

In July 2013, the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) began to forcibly displace Kurdish civilians from towns in Raqqa Governorate. After demanding that all Kurds leave Tell Abyad or else be killed, thousands of civilians, including Turkmens and Arabs, fled on 21 July. ISIL fighters looted and destroyed the property of Kurds, and in some cases, resettled displaced Sunni Arab families from the an-Nabek District (Rif Damascus), Deir ez-Zor and Raqqa, in abandoned Kurdish homes. A similar pattern was documented in Tel Arab and Tal Hassel in July 2013. As ISIL consolidated its authority in Raqqa, Kurdish civilians were forcibly displaced from Tel Akhader, and from the immediate Kobanî area, in March and September 2014, respectively.[9]

Euphrates Region has seen fighting with the Islamic State since 2014. In September 2014, ISIL launched a major assault against the Euphrates Region, capturing more than 100 Kurdish villages.[10][11] As a consequence of the ISIL occupation, up to 200,000 Kurdish refugees fled from the Euphrates Region to Turkey, allowed in only under the condition that they left their vehicles and livestock behind.[10][12] While committing massacres and kidnapping women in the seized villages,[11] ISIL forces were not able to occupy the entire region, as the People's Protection Units (YPG) and Women's Protection Units (YPJ) forces successfully put up stiff resistance in the city of Kobanî. After weeks of isolation as a result of Turkey blocking arms and fighters from entering the city, the US-led coalition finally began to target the ISIL assault forces with airstrikes. This move helped the YPG/YPJ to force ISIL to retreat from the city, and much of the surrounding region was retaken by Kurdish forces.[13] After the successful summer 2015 Tell Abyad offensive of YPG/YPJ forces against ISIL, municipalities there voted to join the autonomous Kobanî Canton administration,[14] creating the region in its contemporary shape.

Politics and administration

[edit]Kobanî's Legislative Assembly has two co-presidents, Lemis Abdullah (an Armenian woman refugee from Tell Abyad), and Mihemed Şahin (a Kurdish man).[15] According to the constitutional Charter of the Social Contract, the Kobanî Canton's Legislative Assembly declared autonomy at its 27 January 2014 session.

Economy

[edit]The economy of the region is mainly based on agriculture, with the introduction of greenhouse agriculture since the establishment of the Euphrates Region.[16]

While there is no significant industrial area in the Euphrates Region, there is a large number of cement production facilities.[17]

Some electricity is supplied by the Tishrin Dam on the Euphrates, also in the Euphrates Region; a lot is also produced by diesel generators.[17]

Around the region, but in particular in the city of Kobanî, economic priorities are the continuing war and reconstruction, including help for returning refugees.[6] Most of the city and surrounding villages have been destroyed or badly damaged, and there is a danger of landmines.[6] As of January 2017, in spite off the paucity of resources available and the embargoes imposed on the region, the rebuilding process has made considerable progress; over 70% of damaged roads have been restored, two hospitals rebuilt and another two added, and the 15 schools rebuilt now host over 50,000 students.[18]

Education

[edit]Like in the other regions in the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria, primary education in public schools is initially instructed according to each student's mother tongue, be it Kurdish or Arabic. Students then begin to learn their second language of Kurdish or Arabic, as well as additional instruction of English. This is due to Rojava's stated goal of students achieving bilingualism in both Kurdish and Arabic by secondary schooling.[19][20] Curricula are a topic of continuous debate between the regions' Boards of Education and the Syrian central government in Damascus, which partly pays the teachers.[21][22][23][24] With Euphrates Region being home to a Syrian Turkmen minority, school education bilingual in Turkish and Arabic has also been made available.[25]

The federal, regional and local administrations in Rojava put much emphasis on promoting libraries and educational centers, to facilitate learning and social and artistic activities. One cited example is the May 2016 established Rodî û Perwîn Library in Kobani.[26]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Abboud 2018, Table 4.1 Cantons of the Rojava Administration.

- ^ "General Census of Population and Housing 2004" (PDF) (in Arabic). Syrian Central Bureau of Statistics. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 15 October 2015. Also available in English: "2004 Census Data". UN OCHA. Archived from the original on 30 May 2019. Retrieved 15 October 2015.

- ^ "Euphrates region within the administrative division". Hawar News. 15 August 2017. Archived from the original on 18 August 2017.

- ^ "Kobane Under Intense ISIS Attack, Excluded from UN Humanitarian Aid". Rudaw. 17 July 2014. Archived from the original on 18 April 2015. Retrieved 20 September 2014.

- ^ "Syria says giving military support to Kurds in Kobani". The Daily Star. Agence France-Presse. October 22, 2014. Archived from the original on October 22, 2014. Retrieved October 14, 2014.

- ^ a b c "The dangerous rebuilding of Kobani". Mashable. Archived from the original on 2015-03-20. Retrieved 2015-03-20.

- ^ Jordi Tejel (2008). Syria's Kurds: History, Politics and Society. Routledge. pp. 10–. ISBN 978-1-134-09643-5.

- ^ "SYRIA: The Silenced Kurds; Vol. 8, No. 4(E)". Human Rights Watch. 1996. Archived from the original on 2017-03-12. Retrieved 2016-12-04.

- ^ "Report of the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic: Twenty-seventh session". UN Human Rights Council. Archived from the original on 2015-11-09. Retrieved 2016-10-27.

- ^ a b Constanze Letsch (22 September 2014). "Isis onslaught against Kurds in Syria brings 'man-made disaster' into Turkey". the Guardian. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- ^ a b "ISIL seizes 21 Kurdish villages in northern Syria, close in on Kobane". AFP/Reuters. 18 September 2014. Archived from the original on 13 July 2018. Retrieved 19 September 2014.

- ^ Ayla Albayrak (17 October 2014). "Hundreds Wait for Kobani Fighting to End, Risking Lives at Border". Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 4 August 2017.

- ^ "YPG official: Airstrikes not enough to protect Kobani". Al-Monitor. 14 October 2014. Archived from the original on 20 October 2014. Retrieved 21 October 2014.

- ^ Tom Perry (21 October 2015). "Town joins Kurdish-led order in Syria, widening sway at Turkish border". Reuters. Archived from the original on 2016-08-19. Retrieved 2016-10-25.

- ^ "Armenian woman at the head of the Euphrates Region Administration". anfenglishmobile.com. 12 February 2020. Archived from the original on 2020-08-03. Retrieved 2020-07-31.

- ^ "Preparations for "Jotkar" agricultural project". UKSSD e. V. 11 February 2016. Archived from the original on 2016-12-20. Retrieved 2016-12-07.

- ^ a b "Rojava: The Economic Branches in Detail". cooperativeeconomy.info. 14 January 2017. Archived from the original on 28 July 2017. Retrieved 16 January 2017.

- ^ Manisha Ganguly (14 January 2017). "Raising Kobanî from Rubble". realmedia.press. Archived from the original on 16 January 2017. Retrieved 16 January 2017.

- ^ "Education in Rojava after the revolution". ANF. 2016-05-16. Archived from the original on 2016-09-24. Retrieved 2016-06-10.

- ^ "After 52-year ban, Syrian Kurds now taught Kurdish in schools". Al-Monitor. 2015-11-06. Archived from the original on 2016-05-10. Retrieved 2016-05-18.

- ^ "Hassakeh: Syriac Language to Be Taught in PYD-controlled Schools". The Syrian Observer. 3 October 2016. Archived from the original on 2016-10-04. Retrieved 2016-10-05.

- ^ "Kurds introduce own curriculum at schools of Rojava". Ara News. 2015-10-02. Archived from the original on 2017-06-06. Retrieved 2016-05-18.

- ^ "Revolutionary Education in Rojava". New Compass. 2015-02-17. Archived from the original on 2020-06-21. Retrieved 2016-05-10.

- ^ "Education in Rojava: Academy and Pluralistic versus University and Monisma". Kurdishquestion. 2014-01-12. Archived from the original on 2016-05-10. Retrieved 2016-05-18.

- ^ "Confederalisme democràtic: Noves classes en llengua turcmana al nord de Síria". KurdisCat. 25 October 2016. Archived from the original on 2016-10-30. Retrieved 2016-10-29.

- ^ "Kurds establish university in Rojava amid Syrian instability". Kurdistan24. 2016-07-07. Archived from the original on 2018-07-18. Retrieved 2016-07-07.

Works cited

[edit]- Abboud, Samer N. (2018). Syria: Hot Spots in Global Politics. Cambridge: Polity. ISBN 978-1-509-52241-5.

External links

[edit]- Map of majority ethnicities in Syria by Gulf2000 project of Columbia University