Carbon fibers

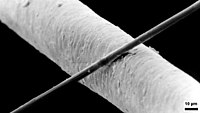

Carbon fiber, alternatively graphite fiber, carbon graphite or CF, is a material consisting of fibers about 5–10 μm in diameter and composed mostly of carbon atoms.

To produce carbon fiber, the carbon atoms are bonded together in crystals that are more or less aligned parallel to the long axis of the fiber as the crystal alignment gives the fiber high strength-to-volume ratio (making it strong for its size). Several thousand carbon fibers are bundled together to form a tow, which may be used by itself or woven into a fabric.

The properties of carbon fibers, such as high stiffness, high tensile strength, low weight, high chemical resistance, high temperature tolerance and low thermal expansion, make them very popular in aerospace, civil engineering, military, and motorsports, along with other competition sports. However, they are relatively expensive when compared to similar fibers, such as glass fibers or plastic fibers.

Carbon fibers are usually combined with other materials to form a composite. When combined with a plastic resin and wound or molded it forms carbon fiber reinforced polymer (often referred to as carbon fiber) which has a very high strength-to-weight ratio, and is extremely rigid although somewhat brittle. However, carbon fibers are also composed with other materials, such as with graphite to form carbon-carbon composites, which have a very high heat tolerance.

History

This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2009) |

In 1958, Roger Bacon created high-performance carbon fibers at the Union Carbide Parma Technical Center, now GrafTech International Holdings, Inc., located outside of Cleveland, Ohio.[1][2] Those fibers were manufactured by heating strands of rayon until they carbonized. This process proved to be inefficient, as the resulting fibers contained only about 20% carbon and had low strength and stiffness properties. In the early 1960s, a process was developed by Dr. Akio Shindo at Agency of Industrial Science and Technology of Japan, using polyacrylonitrile (PAN) as a raw material. This had produced a carbon fiber that contained about 55% carbon.

The high potential strength of carbon fiber was realized in 1963 in a process developed by W. Watt, L. N. Phillips, and W. Johnson at the Royal Aircraft Establishment at Farnborough, Hampshire. The process was patented by the UK Ministry of Defence then licensed by the National Research Development Corporation (NRDC) to three British companies: Rolls-Royce, already making carbon fiber; Morganite; and Courtaulds. They were able to establish industrial carbon fiber production facilities within a few years, and Rolls-Royce took advantage of the new material's properties to break into the American market with its RB-211 aero-engine.

Public concern arose over the ability of British industry to make the best of this breakthrough. In 1969 a House of Commons select committee inquiry into carbon fiber prophetically asked: "How then is the nation to reap the maximum benefit without it becoming yet another British invention to be exploited more successfully overseas?" Ultimately, this concern was justified. One by one the licensees pulled out of carbon-fiber manufacture. Rolls-Royce's interest was in state-of-the-art aero-engine applications. Its own production process was to enable it to be leader in the use of carbon-fiber reinforced plastics. In-house production would typically cease once reliable commercial sources became available.

Unfortunately, Rolls-Royce pushed the state-of-the-art too far, too quickly, in using carbon fiber in the engine's compressor blades, which proved vulnerable to damage from bird impact. What seemed a great British technological triumph in 1968 quickly became a disaster as Rolls-Royce's ambitious schedule for the RB-211 was endangered. Indeed, Rolls-Royce's problems became so great that the company was eventually nationalized by the British government in 1971 and the carbon-fiber production plant was sold off to form "Bristol Composites".

Given the limited market for a very expensive product of variable quality, Morganite also decided that carbon-fiber production was peripheral to its core business, leaving Courtaulds as the only big UK manufacturer. Continuing collaboration with the staff at Farnborough proved helpful in the quest for higher quality and improvements in the speed of production as Courtaulds developed two main markets: aerospace and sports equipment.. However Courtaulds's big advantage as manufacturer of the "Courtelle" precursor now became a weakness. Courtelle's low cost and ready availability were potential advantages, but the water-based inorganic process used to produce it made the product susceptible to impurities that did not affect the organic process used by other carbon-fiber manufacturers.

Nevertheless, during the 1980s Courtaulds continued to be a major supplier of carbon fiber for the sports-goods market, with Mitsubishi its main customer until a move to expand, including building a production plant in California, turned out badly. The investment did not generate the anticipated returns, leading to a decision to pull out of the area and Courtaulds ceased carbon-fiber production in 1991. Ironically the one surviving UK carbon-fiber manufacturer continued to thrive making fiber based on Courtaulds's precursor. Inverness-based RK Carbon Fibres Ltd concentrated on producing carbon fiber for industrial applications, removing the need to compete at the quality levels reached by overseas manufacturers.

During the 1970s, experimental work to find alternative raw materials led to the introduction of carbon fibers made from a petroleum pitch derived from oil processing. These fibers contained about 85% carbon and had excellent flexural strength. Also, during this period, the Japanese Government heavily supporting carbon fiber development at home and several Japanese companies such as Toray, Nippon Carbon, Toho Rayon and Mitsubishi started their own development and production. As they subsequently advanced to become market leaders, companies in USA and Europe were encouraged to take up these activities as well, either through their own developments or contractual acquisition of carbon fiber knowledge. These companies included Hercules, BASF and Celanese USA and Akzo in Europe.

During this period of advancement, further types of carbon fiber yarn entered the global market, offering higher tensile strength and higher elastic modulus. For example T400 from Toray with a tensile strength of 4,000 MPa and M40, a modulus of 400 GPa. Intermediate carbon fibers, such as IM 600 from Toho Reyon with up to 6,000 MPa were developed. Carbon fibers from Toray, Celanese and Akzo found their way to aerospace application from secondary to primary parts first in military and later in civil aircraft as in McDonnell Douglas, Boeing and Airbus planes. By 2000 the industrial applications for high sophisticated machine parts in middle Europe was becoming more important.

Structure and properties

Each carbon filament thread is a bundle of many thousand carbon filaments. A single such filament is a thin tube with a diameter of 5–8 micrometers and consists almost exclusively of carbon. The earliest generation (e.g. T300, HTA and AS4) had diameters of 16–22 micrometers.[3] Later fibers (e.g. IM6 or IM600) have diameters that are approximately 5 micrometers.[3]

The atomic structure of carbon fiber is similar to that of graphite, consisting of sheets of carbon atoms (graphene sheets) arranged in a regular hexagonal pattern, the difference being in the way these sheets interlock. Graphite is a crystalline material in which the sheets are stacked parallel to one another in regular fashion. The intermolecular forces between the sheets are relatively weak Van der Waals forces, giving graphite its soft and brittle characteristics.

Depending upon the precursor to make the fiber, carbon fiber may be turbostratic or graphitic, or have a hybrid structure with both graphitic and turbostratic parts present. In turbostratic carbon fiber the sheets of carbon atoms are haphazardly folded, or crumpled, together. Carbon fibers derived from Polyacrylonitrile (PAN) are turbostratic, whereas carbon fibers derived from mesophase pitch are graphitic after heat treatment at temperatures exceeding 2200 °C. Turbostratic carbon fibers tend to have high tensile strength, whereas heat-treated mesophase-pitch-derived carbon fibers have high Young's modulus (i.e., high stiffness or resistance to extension under load) and high thermal conductivity.

Applications

The global demand on carbon fiber composites was valued at roughly US$10.8 billion in 2009, which declined 8–10% from the previous year. It is expected to reach US$13.2 billion by 2012 and to increase to US$18.6 billion by 2015 with an annual growth rate of 7% or more. Strongest demands come from aircraft & aerospace, wind energy, as well as from the automotive industry[4] with optimized resin systems.[5]

Composite materials

Carbon fiber is most notably used to reinforce composite materials, particularly the class of materials known as carbon fiber or graphite reinforced polymers. Non-polymer materials can also be used as the matrix for carbon fibers. Due to the formation of metal carbides and corrosion considerations, carbon has seen limited success in metal matrix composite applications. Reinforced carbon-carbon (RCC) consists of carbon fiber-reinforced graphite, and is used structurally in high-temperature applications. The fiber also finds use in filtration of high-temperature gases, as an electrode with high surface area and impeccable corrosion resistance, and as an anti-static component. Molding a thin layer of carbon fibers significantly improves fire resistance of polymers or thermoset composites because a dense, compact layer of carbon fibers efficiently reflects heat.[6]

The increasing use of carbon fiber composites is displacing aluminum from aerospace applications in favor of other metals because of galvanic corrosion issues.[7][8]

Textiles

Precursors for carbon fibers are polyacrylonitrile (PAN), rayon and pitch. Carbon fiber filament yarns are used in several processing techniques: the direct uses are for prepregging, filament winding, pultrusion, weaving, braiding, etc. Carbon fiber yarn is rated by the linear density (weight per unit length, i.e. 1 g/1000 m = 1 tex) or by number of filaments per yarn count, in thousands. For example, 200 tex for 3,000 filaments of carbon fiber is three times as strong as 1,000 carbon filament yarn, but is also three times as heavy. This thread can then be used to weave a carbon fiber filament fabric or cloth. The appearance of this fabric generally depends on the linear density of the yarn and the weave chosen. Some commonly used types of weave are twill, satin and plain. Carbon filament yarns can be also knitted or braided.

Microelectrodes

Carbon fibers are used for fabrication of carbon-fiber microelectrodes. In this application typically a single carbon fiber with diameter of 5–7 μm is sealed in a glass capillary.[9] At the tip the capillary is either sealed with epoxy and polished to make carbon-fiber disk microelectrode or the fiber is cut to a length of 75–150 μm to make carbon-fiber cylinder electrode. Carbon-fiber microelectrodes are used either in amperometry or fast-scan cyclic voltammetry for detection of biochemical signaling.

Catalysis

PAN-based nanofibers can efficiently catalyze the first step in the making of synthetic gasoline (syngas) and other energy-rich products out of carbon dioxide. The process uses a “co-catalyst” system in three steps: (1) EMIM–CO2 complex formation; (2) adsorption of EMIM–CO2 complex on reduced carbon atoms and (3) Carbon monoxide formation.[10]

The first step uses an ionic liquid, while graphitic carbon structures doped with other reactive atoms replaced silver to produce the final output. The carbon nanofibre catalyst exhibited negligible overpotential (0.17 V) for carbon dioxide reduction and more than an order of magnitude higher current density compared with silver under similar experimental conditions. The reduction derived from the reduced carbons rather than to electronegative nitrogen dopants. The performance came from the nanofibrillar structure and high binding energy of key intermediates to the carbon nanofibre surfaces.[11][10]

Synthesis

Each carbon filament is produced from a precursor polymer such as polyacrylonitrile (PAN), rayon, or petroleum pitch. For synthetic polymers such as PAN or rayon, the precursor is first spun into filament yarns, using chemical and mechanical processes to initially align the polymer atoms in a way to enhance the final physical properties of the completed carbon fiber. Precursor compositions and mechanical processes used during spinning filament yarns may vary among manufacturers. After drawing or spinning, the polymer filament yarns are then heated to drive off non-carbon atoms (carbonization), producing the final carbon fiber. The carbon fibers filament yarns may be further treated to improve handling qualities, then wound on to bobbins.[12]

A common method of manufacture involves heating the spun PAN filaments to approximately 300 °C in air, which breaks many of the hydrogen bonds and oxidizes the material. The oxidized PAN is then placed into a furnace having an inert atmosphere of a gas such as argon, and heated to approximately 2000 °C, which induces graphitization of the material, changing the molecular bond structure. When heated in the correct conditions, these chains bond side-to-side (ladder polymers), forming narrow graphene sheets which eventually merge to form a single, columnar filament. The result is usually 93–95% carbon. Lower-quality fiber can be manufactured using pitch or rayon as the precursor instead of PAN. The carbon can become further enhanced, as high modulus, or high strength carbon, by heat treatment processes. Carbon heated in the range of 1500–2000 °C (carbonization) exhibits the highest tensile strength (820,000 psi, 5,650 MPa or N/mm²), while carbon fiber heated from 2500 to 3000 °C (graphitizing) exhibits a higher modulus of elasticity (77,000,000 psi or 531 GPa or 531 kN/mm²).

Manufacturers

Major manufacturers of carbon fibers include Cytec Industries, Formosa Plastics, Hexcel, Mitsubishi Rayon, SGL Carbon, Toho Tenax, Toray Industries and Zoltek. Manufacturers typically make different grades of fibers for different applications. Higher modulus carbon fibers are typically more expensive.[13]

See also

- Carbon fiber reinforced polymer

- Carbon fiber reinforced ceramic material

- Carbon nanotube

- ESD materials

References

- ^ Bacon, R. "Filamentary graphite and method for producing the same" U.S. patent 2,957,756, Priority date March 18, 1958

- ^ "High Performance Carbon Fibers". National Historic Chemical Landmarks. American Chemical Society. Retrieved March 25, 2013.

- ^ a b W.J. Cantwell, J Morton (1991). "The impact resistance of composite materials – a review". Composites. 22 (5): 347–62. doi:10.1016/0010-4361(91)90549-V.

- ^ "Market Report: World Carbon Fiber Composite Market". Acmite Market Intelligence. July 2010.

- ^ Roman Hillermeier, Tareq Hasson, Lars Friedrich, Cedric Ball. "Advanced Thermosetting Resin Matrix Technology for Next Generation High Volume Manufacture of Automotive Composite Structures" (PDF). speautomotive.com.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Zhao, Z. and Gou, J. (2009). "Improved fire retardancy of thermoset composites modified with carbon nanofibers". Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 10: 015005. doi:10.1088/1468-6996/10/1/015005.

{{cite journal}}:|format=requires|url=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Design for Corrosion." boeing.co

- ^ Warwick, Graham and Norris, Guy (May 6, 2013) "Metallics Make Comeback With Manufacturing Advances." Aviation Week & Space Technology

- ^ Pike, Carolyn M. (4 May 2009). "Fabrication of Amperometric Electrodes". Journal of Visualized Experiments (27). doi:10.3791/1040.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "A new process for producing synthetic gasoline based on carbon nanofibers". KurzweilAI. 2013-12-04. doi:10.1038/ncomms3819. Retrieved 2013-12-08.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1038/ncomms3819, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1038/ncomms3819instead. - ^ "How It Is Made". zoltek.com.

- ^ Johnson, Todd. Carbon Fiber Manufacturers. About.com.

External links

- Making Carbon Fiber

- How carbon fiber is made

- Carbon Fibres – the First Five Years A 1971 Flight article on carbon fibre in the aviation field