Carleton S. Coon

Carleton S. Coon | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Carleton Stevens Coon June 23, 1904 |

| Died | June 3, 1981 (aged 76) |

| Nationality | United States of America |

| Alma mater | Harvard University |

| Known for | Racial theory and origins |

| Spouse(s) | Mary Goodale (1926 – circa 1945), Lisa Dougherty Geddes (1945 – ) |

| Awards | Legion of Merit Viking Fund Medal (1951) Gold Medal of the Philadelphia Athenæum |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Anthropology |

| Institutions | Harvard University, University of Pennsylvania |

Carleton Stevens Coon (June 23, 1904 – June 3, 1981) was an American physical anthropologist, Professor of Anthropology at the University of Pennsylvania, lecturer and professor at Harvard University, and president of the American Association of Physical Anthropologists.[1]

Biography

Carleton Coon was born in Wakefield, Massachusetts to a Cornish American family.[2] He developed an interest in prehistory, and attended Phillips Academy, Andover. Coon matriculated to Harvard University, where he was attracted to the relatively new field of anthropology by Earnest Hooton and he graduated magna cum laude in 1925. He became the Curator of Ethnology at the University Museum of Philadelphia.[3][4] Coon continued with coursework at Harvard. He conducted fieldwork in the Rif area of Morocco in 1925, which was politically unsettled after a rebellion of the local populace against the Spanish. He earned his Ph.D. in 1928[5] and returned to Harvard as a lecturer and later a professor. Coon's interest was in attempting to use Darwin's theory of natural selection to explain the differing physical characteristics of races. Coon studied Albanians from 1920 to 1930; he traveled to Ethiopia in 1933; and in Arabia, North Africa and the Balkans, he worked on sites from 1925 to 1939, where he discovered a Neanderthal in 1939. Coon rewrote William Z. Ripley's 1899 The Races of Europe in 1939.

Coon wrote widely for a general audience like his mentor Earnest Hooton. Coon published The Riffians, Flesh of the Wild Ox, Measuring Ethiopia, and A North Africa Story: The Anthropologist as OSS Agent. A North Africa Story was an account of his work in North Africa during World War II, which involved espionage and the smuggling of arms to French resistance groups in German-occupied Morocco under the guise of anthropological fieldwork. During that time, Coon was affiliated with the United States Office of Strategic Services, the forerunner to the Central Intelligence Agency.

Coon left Harvard to take up a position as Professor of Anthropology at the University of Pennsylvania in 1948, which had an excellent museum. Throughout the 1950s he produced academic papers, as well as many popular books for the general reader, the most notable being The Story of Man (1954).

Coon did photography work for the United States Air Force from 1954-1957. He photographed areas where US planes might be attacked. This led him to travel throughout Korea, Ceylon, India, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Japan, Taiwan, Nepal, Sikkim, and the Philippines.

Coon published The Origin of Races in 1962. In its "Introduction" he described the book as part of the outcome of his project he conceived (in light of his work on The Races of Europe) around the end of 1956, for a work to be titled along the lines of Races of the World. He said that since 1959 he had proceeded with the intention to follow The Origin of Races with a sequel, so the two would jointly fulfill the goals of the original project.[6] (He indeed published The Living Races of Man in 1965.) The book asserted that the human species divided into five races before it had evolved into Homo sapiens. Further, he suggested that the races evolved into Homo sapiens at different times. It was not well received.[7] The field of anthropology was moving rapidly from theories of race typology, and The Origin of Races was widely castigated by his peers in anthropology as supporting racist ideas with outmoded theory and notions which had long since been repudiated by modern science. One of his harshest critics, Theodore Dobzhansky, scorned it as providing "grist for racist mills".[8]

He continued to write and defend his work, publishing two volumes of memoirs in 1980 and 1981.[9]

He died on June 3, 1981, in Gloucester, Massachusetts.

Racial theories

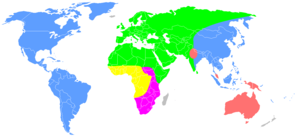

| Caucasoid race | |

| Congoid race | |

| Capoid race | |

| Mongoloid race | |

| Australoid race |

Coon concluded that sometimes different racial types annihilated other types, while in other instances warfare and/or settlement led to the partial displacement of racial types. He asserted that Europe was the refined product of a long history of racial progression. He also posited that historically "different strains in one population have showed differential survival values and often one has reemerged at the expense of others (in Europeans)", in The Races of Europe, The White Race and the New World (1939).[10]

Coon suggested that the "maximum survival" of the European racial type was increased by the replacement of the indigenous peoples of the New World.[10] He stated the history of the White race to have involved "racial survivals" of White subraces.[11]

Study of the Caucasoid race

In his book The Races of Europe, The White Race and the New World (1939), Coon used the term "Caucasoid" and "White race" synonymously, as had become common in the United States, although not elsewhere. This is in contrast to many uses of the term "White race", which tend to reserve the designation for Caucasoid peoples from Europe and their descendants. In his introduction, Coon stated his interest was "the somatic character of peoples belonging to the white race". His first chapter was entitled, "Introduction to the Historical Study of the White Race", and his last chapter, "The White Race and the New World".[12]

Coon considered the European racial type to be a sub-race of the Caucasoid race, one that warranted more study. In other sections of The Races of Europe, he mentioned people to be "European in racial type" and having a "European racial element."[13]

Coon suggested that the study of some major versions of European racial types was sadly lacking compared with other types, writing,

"For many years physical anthropologists have found it more amusing to travel to distant lands and to measure small remnants of little known or romantic peoples than to tackle the drudgery of a systematic study of their own compatriots. For that reason, sections in the present book that deal with the Lapps, the Arabs, the Berbers, the Tajiks, and the Ionians may appear more fully and more lucidly treated than those that deal with the French, the Hungarians, the Czechs, or the English. What is needed more than anything else in this respect is a thoroughgoing study of the inhabitants of the principal and most powerful nations of Europe."[10]

Summary of The Races of Europe[10]

Coon's 1939 book concluded the following:

- The Caucasian race is of dual origin consisting of Upper Paleolithic (mixture of Homo sapiens and Neanderthals) types and Mediterranean (purely sapiens) types.

- The Upper Paleolithic peoples are the truly indigenous peoples of Europe.

- Mediterraneans invaded Europe in large numbers during the Neolithic period and settled there.

- The racial situation in Europe today may be explained as a mixture of Upper Paleolithic survivors and Mediterraneans.

- When reduced Upper Paleolithic survivors and Mediterraneans mix, then occurs the process of dinarization, which produces a hybrid with non-intermediate features.

- The Caucasian race encompasses the regions of Europe, Central Asia, South Asia, the Near East, North Africa, and the Horn of Africa.

- The Nordic race is part of the Mediterranean racial stock, being a mixture of Corded and Danubian Mediterraneans.

Mediterranean race

According to Carleton Coon the "homeland and cradle" of the Mediterranean race is in the Middle East, in the area from Morocco to Afghanistan.[14] Coon argued that smaller Mediterraneans traveled by land from the Mediterranean basin north into Europe in the Mesolithic era. Taller Mediterraneans (Atlanto-Mediterraneans) were Neolithic seafarers who sailed in reed-type boats and colonized the Mediterranean basin from a Near Eastern origin.[14]

While often characterized by dark brown hair, dark eyes and robust features, he stressed that Mediterraneans skin is, as a rule, some shade of white from pink to light brown, hair is usually black or dark brown but his whiskers may reveal a few strands of red of even blond, and blond hair is an exception but can be found, and a wide range of eye color can be found. He stressed the central role of the Mediterraneans in his works, claiming "The Mediterraneans occupy the center of the stage; their areas of greatest concentration are precisely those where civilization is the oldest. This is to be expected, since it was they who produced it and it, in a sense, that produced them".[14]

Racial origins

Coon first modified Franz Weidenreich's Polycentric (or multiregional) theory of the origin of races. The Weidenreich Theory states that human races have evolved independently in the Old World from Homo erectus to Homo sapiens sapiens, while at the same time there was gene flow between the various populations. Coon held a similar belief that modern humans, Homo sapiens, arose separately in five different places from Homo erectus, "as each subspecies, living in its own territory, passed a critical threshold from a more brutal to a more sapient state", but unlike Weidenreich stressed gene flow far less.[15][16]

Coon's modified form of the Weidenreich Theory is sometimes referred to as the Candelabra Hypothesis. A misunderstanding however has led some to believe that Coon supported parallel evolution or polygenism; this is not true since Coon's evolution model still allows for gene-flow, although he did not stress it.[17]

In his 1962 book, The Origin of Races, Coon theorized that some races reached the Homo sapiens stage in evolution before others, resulting in the higher degree of civilization among some races.[18] He had continued his theory of five races. He considered both what he called the Mongoloid race and the Caucasoid race had individuals who had adapted to crowding through evolution of the endocrine system, which made them more successful in the modern world of civilization. This can be found on pages 108-109 of The Origin of Races. In his book Coon contrasted a picture of an Indigenous Australian with one of a Chinese professor. His caption "The Alpha and the Omega" was used to demonstrate his research that brain size was positively correlated with intelligence.

Wherever Homo arose, and Africa is at present the most likely continent, he soon dispersed, in a very primitive form, throughout the warm regions of the Old World....If Africa was the cradle of mankind, it was only an indifferent kindergarten. Europe and Asia were our principal schools.

By this he meant that the Caucasoid and Mongoloid races had evolved more in their separate areas after they had left Africa in a primitive form. He also believed, "The earliest Homo sapiens known, as represented by several examples from Europe and Africa, was an ancestral long-headed white man of short stature and moderately great brain size." Further, he wrote, "The negro group probably evolved parallel to the white strain." (The Races of Europe, Chapter II).

Races in the Indian Sub-Continent

Coon's understanding of racial typology and diversity within the Indian sub-continent changed over time. In The Races of Europe, he regarded the so-called "Veddoids" of India ("tribal" Indians, or "Adivasi") as closely related to other peoples in the South-Pacific ("Australoids"), and he also believed that this supposed human lineage (the "Australoids") was an important genetic substratum in Southern India. As for the north of the sub-continent, it was an extension of the Caucasoid range.[19] By the time Coon coauthored The Living Races of Man, he thought that India's Adivasis were an ancient Caucasoid-Australoid mix who tended to be more Caucasoid than Australoid (with great variability), that the Dravidian peoples of Southern India were simply Caucasoid, and that the north of the sub-continent was also Caucasoid. In short, the Indian sub-continent (North and South) is "the easternmost outpost of the Caucasoid racial region".[20] Underlying all of this was Coon's typological view of human history and biological variation, a way of thinking that is not taken seriously today by most anthropologists/biologists.[21][22][23][24] Like all world regions, it is now understood by most scientists that the Indian sub-continent bleeds genetically into neighboring regions, being structured fluidly and continuously in a loose pattern of isolation-by-distance. Nevertheless, Coon's views are of historical interest, and are part of a long line of western anthropology which has sought to describe and conceptualize biological diversity in the sub-continent.

Criticism

Contemporary reception

Coon's published magnum opus The Origin of Races (1962) received mixed reactions from scientists of the era.

Positive

Ernst Mayr praised the work for its synthesis as having an "invigorating freshness that will reinforce the current revitalization of physical anthropology".[25]

In a book review by Stanley Marion Garn, while criticising Coon's parallel view of the origin of the races with little gene flow, nonetheless praises the work for its racial taxonomy, and concludes: "an overall favorable report on the now famous Origin of Races".[26]

Negative

Sherwood Washburn and Ashley Montagu were heavily influenced by the modern synthesis in biology and population genetics. In addition, they were influenced by Franz Boas, who had moved away from typological racial thinking. Rather than supporting Coon's theories, they and other contemporary researchers viewed the human species as a continuous serial progression of populations and heavily criticised Coon's Origin of Races.

The Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s and changing social attitudes challenged racial theories like Coon's that had been used by segregationists to justify discrimination and depriving people of civil rights. In 1961 non-fiction writer Carleton Putnam published Race and Reason: A Yankee View, a popular theory of racial segregation. A special session of the American Association of Physical Anthropologists voted to censure Putnam's book. Coon, who was then the president of the association, and was present at the meeting, asked how many of the participants had actually read the book; only one hand was raised in response. Coon resigned in protest, criticizing the meeting for representing scientific irresponsibility[27] and arguing its actions violated free speech.[28]

Posthumous reputation

William W. Howells writing in an 1989 article, notes that Coon's research is "still regarded as a valuable source of data".[29]

In 2001 John P. Jackson, Jr. researched Coon's papers in order to review the controversy around the reception of The Origin of Races, stating in the article abstract

- Segregationists in the United States used Coon’s work as proof that African Americans were "junior" to white Americans, and thus unfit for full participation in American society. The paper examines the interactions among Coon, segregationist Carleton Putnam, geneticist Theodosius Dobzhansky, and anthropologist Sherwood Washburn. The paper concludes that Coon actively aided the segregationist cause in violation of his own standards for scientific objectivity.[30]

Jackson found in the archived Coon papers records of repeated efforts by Coon to aid Putnam's efforts to provide intellectual support to the ongoing resistance to racial integration, while cautioning Putnam against statements that could identify Coon as an active ally. (Jackson also noted that both men had become aware that they had American-Revolutionary Gen. Israel Putnam as a common ancestor, making them (at least distant) cousins, but Jackson indicated neither when either learned of the family relationship nor whether they had a more recent common ancestor.)[30]

Alan H. Goodman (2000) has noted Coon's main legacy was not his "separate evolution of races (Coon 1962)" but his "molding of race into the new physical anthropology of adaptive and evolutionary processes (Coon et al. 1950)" since he attempted to "unify a typological model of human variation with an evolutionary perspective and explained racial differences with adaptivist arguments."[31]

Works

Science:

- The Origin of Races (1962)

- The Story of Man (1954)

- The Races of Europe (1939)

- Caravan: the Story of the Middle East (1958)

- Races: A Study of the Problems of Race Formation in Man

- The Hunting Peoples

- Anthropology A to Z (1963)

- Living Races of Man (1965)

- Seven Caves: Archaeological Exploration in the Middle East

- Mountains of Giants: A Racial and Cultural Study of the North Albanian Mountain Ghegs

- Yengema Cave Report (his work in Sierra Leone)

- Racial Adaptations (1982)

Fiction and Memoir:

- Flesh of the Wild Ox (1932)

- The Riffian (1933)

- A North Africa Story: Story of an Anthropologist as OSS Agent (1980)

- Measuring Ethiopia

- Adventures and Discoveries: The Autobiography of Carleton S. Coon (1981)

References

Citations

- ^ “Race” Relations: Montagu, Dobzhansky, Coon, and the Divergence of Race Concepts

- ^ Rowse, A.L. The Cousin Jacks, The Cornish in America

- ^ Coon, Carleton S. (1962). The Origins of Races. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

- ^ Howells, H. W. (1989). Carleton Stevens Coon 1904—1981: A Biographical Memoir (PDF). Washington D.C.: National Academy of Sciences.

- ^ The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition. 2005.

- ^ Carleton S. Coon, The Origin of Races, Knopf, 1962, p. vii

- ^ Harold M. Schmeck Jr. (June 6, 1981). "Carleton S. Coon Is Dead at 76: Pioneer in Social Anthropology". New York Times.

- ^ Shipman, Pat (2002). The Evolution of Racism: Human Differences and the Use and Abuse of Science. Harvard University Press. p. 207. ISBN 978-0-674-00862-5.

- ^ National Anthropological Archives, "Coon, Carleton Stevens (1904-1981), Papers"

- ^ a b c d The Races of Europe by Carleton Coon 1939 (Hosted by the Society for Nordish Physical Anthropology)

- ^ The Races of Europe, Chapter II, Section 12 Archived June 14, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ The Races of Europe, Chapter XIII, Section 2 Archived May 11, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ The Races of Europe, Chapter 7, Section 2 Archived June 14, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c "Our area, from Morocco to Afghanistan, is the homeland and cradle of the Mediterranean race. Mediterraneans are found also in Spain, Portugal, most of Italy, Greece and the Mediterranean islands, and in all these places, as in the Middle East, they form the major genetic element in the local populations. In a dark-skinned and finer-boned form they are also found as the major population element in Pakistan and northern India ... The Mediterranean race, then, is indigenous to, and the principal element in, the Middle East, and the greatest concentration of a highly evolved Mediterranean type falls among two of the most ancient Semitic-speaking peoples, notably the Arabs and the Jews. (Although it may please neither party, this is the truth.) The Mediterraneans occupy the center of the stage; their areas of greatest concentration are precisely those where civilization is the oldest. This is to be expected, since it was they who produced it and it, in a sense, that produced them.", Carleton Coon, the Story of the Middle East, 1958, pp. 154-157

- ^ The Origin of Races: Weidenreich's Opinion, S. L. Washburn, American Anthropologist, New Series, Vol. 66, No. 5 (Oct. 1964) (pp. 1165-1167).

- ^ An Attempted Revival of the Race Concept, Leonard Lieberman, American Anthropologist, New Series, Vol. 97, No. 3 (Sep. 1995), pp. 590-592.

- ^ Coon's Theory on "The Origin of Races", Bruce G. Trigger, Anthropologica, New Series, Vol. 7, No. 2 (1965), pp. 179-187.

- ^ Coon, Carleton S. (1962) . The Origins of Races. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

- ^ The Races of Europe, The Veddoid Periphery, Hadhramaut to Baluchistan

- '^ The Living Races of Man, On Greater India

- ^ Non-Darwinian estimation: My ancestors, my genes' ancestors

- ^ http://www.unl.edu/rhames/courses/current/readings/templeton.pdf

- ^ Welcome

- ^ Race reconciled?: How biological anthropologists view human variation - Edgar - 2009 - American Journal of Physical Anthropology - Wiley Online Library

- ^ Origin of the Human Races, Ernst Mayr, Science, New Series, Vol. 138, No. 3538, (October 19, 1962), pp. 420-422.

- ^ The Origin of Races. by Carleton S. Coon, Review by: Stanley M. Garn, American Sociological Review, Vol. 28, No. 4 (Aug. 1963), pp. 637-638/

- ^ Pat Shipman (1994). The Evolution of Racism: Human Differences and the Use and Abuse of Science. Harvard University Press. p. 200. ISBN 0674008626.

- ^ Academic American Encyclopedia (vol. 5, p.271). Danbury, Connecticut: Grolier Incorporated (1995).

- ^ . W. Howells. "Biographical Memoirs V.58". National Academy of Sciences, 1989.[1]

- ^ a b Jackson, John P. (2001). ""In Ways Unacademical": The Reception of Carleton S. Coon's The Origin of Races" (PDF). Journal of the History of Biology. 34 (2): 247–285. doi:10.1023/A:1010366015968. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 14, 2013.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Goodman, A., & Hammonds, E. (2000). Reconciling race and human adaptability: Carleton Coon and the persistence of race in scientific discourse. Kroeber Anthropological Society Papers, 28-44.

Further reading

- The Lagar Velho 1 Skeleton

- Hybrid Humans? Archaeological Institute of America Volume 52 Number 4, July/August 1999 by Spencer P.M. Harrington [2]

- Two Views of Coon's Origin of Races with Comments by Coon and Replies. 1963. Theodosius Dobzhansky; Ashley Montagu; C. S. Coon in Current Anthropology, Vol. 4, No. 4. (Oct. 1963), pp. 360–367.

- Jackson, John P. (2005). Science for Segregation: Race, Law, and the Case against Brown v. Board of Education. NYU Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-4271-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|laydate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysummary=ignored (help) - The Races of Europe (1939)[3] by Carleton S. Coon - physical anthropological information on the indigenous peoples of Europe.

- Tucker, William H. (2007). The funding of scientific racism: Wickliffe Draper and the Pioneer Fund. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-07463-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|laydate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysummary=ignored (help)

External links

- Carleton Stevens Coon Papers, National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution

- Caravan: The Story of the Middle East

- National Academy of Sciences Biographical Memoir

- 1904 births

- 1981 deaths

- People from Wakefield, Massachusetts

- American Congregationalists

- American anthropologists

- People of the Office of Strategic Services

- Phillips Academy alumni

- Harvard University alumni

- Harvard University faculty

- University of Pennsylvania faculty

- Race and intelligence controversy

- American people of Cornish descent

- Recipients of the Legion of Merit

- 20th-century American writers