Colon (anatomy)

It has been suggested that this article be merged into Large intestine. (Discuss) Proposed since March 2014. |

| Colon (anatomy) | |

|---|---|

| |

Front of abdomen, showing surface markings for liver, stomach, and large intestine. | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Colon |

| MeSH | D003106 |

| TA98 | A05.7.03.001 |

| TA2 | 2981 |

| FMA | 14543 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The colon is the last part of the digestive system in most vertebrates. It extracts water and salt from solid wastes before they are eliminated from the body and is the site in which flora-aided (large bacterial) fermentation of unabsorbed material occurs. Unlike the small intestine, the colon does not play a major role in absorption of foods and nutrients. However, the colon does absorb water, sodium and some fat soluble vitamins.[1]

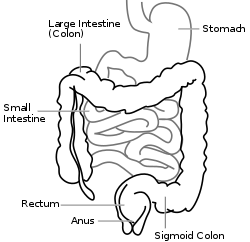

In mammals, the colon consists of four sections: the ascending colon, the transverse colon, the descending colon, and the sigmoid colon (the proximal colon usually refers to the ascending colon and transverse colon). The cecum, colon, rectum and anal canal make up the large intestine.[2]

Anatomy

The parts of the colon are either in the abdominal cavity (intraperitoneal) or behind it in the retroperitoneum. Retroperitoneal organs in general do not have a complete covering of peritoneum, so they are fixed in location. Intraperitoneal organs are completely surrounded by peritoneum and are therefore mobile.[3]

Of the colon, the ascending colon, descending colon and rectum are retroperitoneal, while the caecum, appendix, transverse colon and sigmoid colon are intraperitoneal.[4] This is important as it affects which organs can be easily accessed during surgery, such as a laparotomy.

The taenia coli run the length of the large intestine. Because the taenia coli are shorter than the large bowel itself, the colon becomes sacculated, forming the haustra of the colon which are the shelf-like intraluminal projections.[5]

Arterial supply to the colon comes from branches of the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) and inferior mesenteric artery (IMA). Flow between these two systems communicates via a "marginal artery" that runs parallel to the colon for its entire length. Historically, it has been believed that the arc of Riolan, or the meandering mesenteric artery (of Moskowitz), is a variable vessel connecting the proximal SMA to the proximal IMA that can be extremely important if either vessel is occluded. However, recent studies conducted with improved imaging technology have questioned the actual existence of this vessel, with some experts calling for the abolition of the terms from future medical literature.

Venous drainage usually mirrors colonic arterial supply, with the inferior mesenteric vein draining into the splenic vein, and the superior mesenteric vein joining the splenic vein to form the hepatic portal vein that then enters the liver.

Lymphatic drainage from the entire colon and proximal two-thirds of the rectum is to the paraaortic lymph nodes that then drain into the cisterna chyli. The lymph from the remaining rectum and anus can either follow the same route, or drain to the internal iliac and superficial inguinal nodes. The pectinate line only roughly marks this transition.

Right and Left Colon

Right colon: consists of the cecum, ascending colon, hepatic flexure, and transverse colon.[6]

Left colon: consists of the splenic flexure, descending colon, sigmoid colon, recto-sigmoid junction, and rectum.[6]

By segment

Ascending colon

The ascending colon is one part of four sections of the large intestine. This first section of the large intestine is connected to the small intestine by a section of bowel called the cecum. The ascending colon runs through the abdominal cavity, upwards toward the transverse colon for approximately eight inches (20 cm).

One of the main functions of the colon is to remove the water and other key nutrients from waste material and recycle it back into the body. As the waste material exits the small intestine it will move into the cecum and then the ascending colon where this process of extracting starts. The waste material is moved upwards toward the transverse section of the colon by a process known as peristalsis.

In ruminants, this is known as the spiral colon.[7] The cecum receives the solid wastes of digestion from the ileum via the Ileocecal valve.[8][9]

Transverse colon

The transverse colon is the part of the colon from the hepatic flexure to the splenic flexure (the turn of the colon by the spleen). The transverse colon hangs off the stomach, attached to it by a wide band of tissue called the greater omentum. On the posterior side, the transverse colon is connected to the posterior abdominal wall by a mesentery known as the transverse mesocolon.

The transverse colon is encased in peritoneum, and is therefore mobile (unlike the parts of the colon immediately before and after it). Cancers form more frequently further along the large intestine as the contents become more solid (water is removed) in order to form feces.

The proximal two-thirds of the transverse colon is perfused by the middle colic artery, a branch of SMA, while the latter third is supplied by branches of the IMA. The "watershed" area between these two blood supplies, which represents the embryologic division between the midgut and hindgut, is an area sensitive to ischemia.

Descending colon

The descending colon is the part of the colon from the splenic flexure to the beginning of the sigmoid colon. The function of the descending colon in the digestive system is to store faeces that will be emptied into the rectum. It is retroperitoneal in two-thirds of humans. In the other third, it has a (usually short) mesentery. The arterial supply comes via the left colic artery.

Sigmoid colon

The sigmoid colon is the part of the large intestine after the descending colon and before the rectum. The name sigmoid means S-shaped (see sigmoid; cf. sigmoid sinus). The walls of the sigmoid colon are muscular, and contract to increase the pressure inside the colon, causing the stool to move into the rectum.

The sigmoid colon is supplied with blood from several branches (usually between 2 and 6) of the sigmoid arteries, a branch of the IMA. The IMA terminates as the superior rectal artery.

Sigmoidoscopy is a common diagnostic technique used to examine the sigmoid colon.

Redundant colon

One variation on the normal anatomy of the colon occurs when extra loops form, resulting in up to five metres longer than normal organ. This condition, referred to as redundant colon, typically has no direct major health consequences, though rarely volvulus occurs resulting in obstruction and requiring immediate medical attention.[10][11] A significant indirect health consequence is that use of a standard adult colonoscope is difficult and in some cases impossible when a redundant colon is present, though specialized variants on the instrument (including the pediatric variant) are useful in overcoming this problem.[12]

Standing gradient osmosis

Water absorption at the colon typically proceeds against a transmucosal osmotic pressure gradient. The standing gradient osmosis is the reabsorption of water against the osmotic gradient in the intestines. This hypertonic fluid creates an osmotic pressure that drives water into the lateral intercellular spaces by osmosis via tight junctions and adjacent cells, which then in turn moves across the basement membrane and into the capillaries.

Function

The large intestine comes after the small intestine in the digestive tract and measures approximately 1.5 meters in length in adult humans. There are differences in the large intestine between different organisms. The large intestine is mainly responsible for storing waste, reclaiming water, maintaining the water balance, absorbing some vitamins, such as vitamin K, and providing a location for flora-aided fermentation.

By the time the chyme has reached this tube, most nutrients and 90% of the water have been absorbed by the body. At this point some electrolytes like sodium, magnesium, and chloride are left as well as indigestible parts of ingested food (e.g., a large part of ingested amylose, starch which has been shielded from digestion heretofore, and dietary fiber, which is largely indigestible carbohydrate in either soluble or insoluble form). As the chyme moves through the large intestine, most of the remaining water is removed, while the chyme is mixed with mucus and bacteria (known as gut flora), and becomes feces. The ascending colon receives fecal material as a liquid. The muscles of the colon then move the watery waste material forward and slowly absorb all the excess water. The stools gradually solidify as they move along into the descending colon.[13] The bacteria break down some of the fiber for their own nourishment and create acetate, propionate, and butyrate as waste products, which in turn are used by the cell lining of the colon for nourishment.[14] No protein is made available. In humans, perhaps 10% of the undigested carbohydrate thus becomes available, though this may vary with diet;[15] in other animals, including other apes and primates, who have proportionally larger colons, more is made available, thus permitting a higher portion of plant material in the diet. The large intestine produces no digestive enzymes -— chemical digestion is completed in the small intestine before the chyme reaches the large intestine. The pH in the colon varies between 5.5 and 7 (slightly acidic to neutral).[16]

Pathology

Following are the most common diseases or disorders of the colon:

- Angiodysplasia of the colon

- Appendicitis

- Chronic functional abdominal pain

- Colitis

- Colorectal cancer

- Colorectal polyp

- Constipation

- Crohn's disease

- Diarrhea

- Diverticulitis

- Diverticulosis

- Hirschsprung's disease (aganglionosis)

- Ileus

- Intussusception

- Irritable bowel syndrome

- Pseudomembranous colitis

- Ulcerative colitis and toxic megacolon

Gallery

-

Intestines

-

Scheme

-

Colon. Deep dissection. Anterior view.

See also

References

- ^ Colon Function And Health Information Retrieved on 2010-01-21

- ^ National Cancer Institute. "NCI Dictionary of Cancer Terms — large intestine". Retrieved 2012-09-16.

- ^ "Peritoneum". Mananatomy.com. 2013-01-18. Retrieved 2013-02-07.

- ^ http://www.ucd.ie/vetanat/ga-subject/abdomen/ab13.html

- ^ Anatomy at a Glance by Omar Faiz and David Moffat

- ^ a b "Trends in Colorectal Cancer Incidence Rates in the United States by Tumor Location and Stage, 1992–2008". Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 21 (3). 411–6 (See section Methods — Statistical analysis). Mar 2012. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-1020. PMID 22219318. Retrieved 2012-10-03.

{{cite journal}}: Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help) - ^ Medical dictionary

- ^ Spiral colon and caecum

- ^ Veterinary Dictionary

- ^ Mayo Clinic Staff (2006-10-13). "Redundant colon: A health concern?". Ask a Digestive System Specialist. MayoClinic.com. Archived from the original on 2007-09-29. Retrieved 2007-06-11.

- ^ Mayo Clinic Staff. "Redundant colon: A health concern? (Above with active image links)". riversideonline.com. Retrieved 8 November 2013.

- ^ Lichtenstein, Gary R. (18 August 1998). "Use of a Push Enteroscope Improves Ability to Perform Total Colonoscopy in Previously Unsuccessful Attempts at Colonoscopy in Adult Patients". The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 94 (1): 187–90. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.00794.x. PMID 9934753.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) Note: single use PDF copy provided free by Blackwell Publishing for purposes of Wikipedia content enrichment. - ^ The Function Of The Colon Retrieved on 2010-01-21

- ^ Terry L. Miller and Meyer J. Wolin (1996). "Pathways of Acetate, Propionate, and Butyrate Formation by the Human Fecal Microbial Flora" (PDF). Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 62 (5): 1589–1592.

- ^ McNeil, NI (1984). "The contribution of the large intestine to energy supplies in man". The American journal of clinical nutrition. 39 (2): 338–342. PMID 6320630.

- ^ Function Of The Large Intestine Retrieved on 2010-01-21

External links

- Overview and diagrams at seer.cancer.gov

- 09-118h. at Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy Home Edition

- Large+Intestine at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Template:IowaHistologyInteractive

- Anatomy photo:37:13-0100 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center - "Abdominal Cavity: The Colon and its Divisions"

- Video: What is Colorectal Cancer? NONE