Congregationalism

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2016) |

| Part of a series on |

| Reformed Christianity |

|---|

|

|

|

Congregational or Congregationalist churches (both terms are used in English) are Protestant churches practicing congregationalist church governance, in which each congregation independently and autonomously runs its own affairs. Congregationalism is often considered to be a part of the wider Reformed tradition.

In the United States and the United Kingdom, many Congregational churches claim their descent from Protestant denominations formed on a theory of union published by the theologian and English separatist Robert Browne in 1582.[1] Ideas of nonconforming Protestants during the Puritan Reformation of the Church of England laid foundation for these churches. In England, the early Congregationalists were called Separatists or Independents to distinguish them from the similarly Calvinistic Presbyterians, whose churches embrace a polity based on the governance of elders. Congregationalists also differed with the Reformed churches using episcopalian church governance, which is usually led by a bishop. Congregational churches were widely established in the Plymouth Colony and the Massachusetts Bay Colony (in present-day New England), and together wrote the Cambridge Platform of 1648 which described the autonomy of the church and its association with others.

Within the United States, the model of Congregational churches was carried by migrating settlers from New England into New York, then into the Old North West, and further. With their insistence on independent local bodies, they became important in many social reform movements, including abolitionism, temperance, and women's suffrage. Modern Congregationalism in the United States is largely split into three bodies: the United Church of Christ, the National Association of Congregational Christian Churches and the Conservative Congregational Christian Conference, which is the most theologically conservative.

Congregationalist tradition has a presence in the United States, the United Kingdom, Ireland, Canada, South Africa, Australia, New Zealand, and various island nations in the Pacific region. It has been introduced either by immigrant dissenter Protestants or by missionary organization such as the London Missionary Society.

Congregationalism, as defined by the Pew Research Center, is estimated to represent 0.5% of the worldwide Protestant population;[2] though their polity-related customs and other ideas influenced significant parts of Protestantism, as well as other Christian congregations. The report defines it very narrowly, encompassing mainly denominations in the United States and the United Kingdom, which can trace their history back to nonconforming Protestants, Puritans, Separatists, Independents, English religious groups coming out of the English Civil War, and other English dissenters not satisfied with the degree to which the Church of England had been reformed.

Origins

Congregationalists believe their model of church governance fulfils the description of the early church and allows people the most direct relationship with God.

Congregationalism is more easily identified as a movement than a single denomination, given its distinguishing commitment to the complete autonomy of the local congregation. The idea that each distinct congregation fully constitutes the visible Body of the church can, however, be traced to John Wycliffe and the Lollard movement, which followed Wycliffe's removal from teaching authority in the Roman Catholic Church.

The early Congregationalists shared with Anabaptist theology the ideal of a pure church. They believed the adult conversion experience was necessary for an individual to become a full member in the church, unlike other Reformed churches. As such, the Congregationalists were a reciprocal influence on the Baptists. They differed in counting the children of believers in some sense members of the church. On the other hand, the Baptists required each member to experience conversion, followed by baptism.

In England, the Anglican system of church government was taken over by King Henry VIII. Influenced by movements for reform and by his desire to legitimize his marriage to Anne Boleyn in 1533 (without the blessing of the Pope) after divorcing his first wife, Catherine of Aragon, Henry's government got Parliament to enact the first Act of Supremacy in 1534. It declared the reigning sovereign of England to be "the only supreme head on earth of the Church in England". In the reign of Elizabeth I, this title was changed to Supreme Governor of the Church of England, an act still in effect. The Church of England ceased to be subject to the Church of Rome, but as the established church it continued to see itself as the Catholic Church in England and for several years continued most of the Roman Catholic traditions.

Robert Browne (1550–1633), Henry Barrow (c. 1550–1593), John Greenwood (died 1593), John Penry (1559–1593), William Brewster (c. 1566–1644), Thomas Jollie (1629–1703) and John Robinson (1576–1625) were notable people who established dissenting churches separate from the Church of England.

The underground churches in England and exiles from Holland provided about 35 out of the 102 passengers on the Mayflower, which sailed from London in July 1620. They became known in history as the Pilgrim Fathers. The early Congregationalists sought to separate themselves from the Anglican church in every possible way and even eschewed having church buildings. They met in homes for many years.

In 1639 William Wroth, then Rector of the parish church at Llanvaches in Monmouthshire, established the first Independent Church in Wales "according to the New England pattern", i.e. Congregational. The Tabernacle United Reformed Church at Llanvaches survives to this day.[3]

During the English Civil War, those who supported the Parliamentary cause were invited by Parliament to discuss religious matters. The Westminster Confession of Faith (1646) was officially declared the statement of faith for both the Church of England (Anglican/Episcopal) and Church of Scotland (Presbyterian), which was politically expedient for those in the Presbyterian dominated English Parliament who approved of the Solemn League and Covenant (1643).

After the Second Civil War, the New Model Army which was dominated by Congregationalists (or Independents) seized control of the parliament with Pride's purge (1648), arranged for the trial and executed Charles I in January 1649 and subsequently introduced a republican Commonwealth dominated by Independents such as Oliver Cromwell. This government would last until 1660 when the monarch was restored and Episcopalism was re-established (see the Penal Laws and Great Ejection).

In 1658 (during the interregnum) the Congregationalists created their own version of the Westminster Confession, called the Savoy Declaration, which remains the principal subordinate standard of Congregationalism.

A summary of Congregationalism in Scotland see the paper presented to a joint meeting of the ministers of the United Reformed Church [Scottish Synod] and the Congregational Federation in Scotland by Rev'd A Paterson is available online.[4]

Beliefs

The two foundational tenets of Congregationalism are sola scriptura and the priesthood of believers. According to Congregationalist minister Charles Edward Jefferson, the priesthood of believers means that "Every believer is a priest and ... every seeking child of God is given directly wisdom, guidance, power."[5] This belief leads Congregationalist Christians to embrace Congregationalist polity, which holds that the members of a local church have the right to decide their church's forms of worship, confessional statements, choose their own officers, and administer their own affairs without any outside interference.[6]

Argentina

The mission to Argentina was the second foreign field tended by German Congregationalists. The work in South America began in 1921 when four Argentine churches urgently requested that denominational recognition be given to George Geier, who was serving them. The Illinois Conference licensed Geier, who worked among Germans from Russia who were very similar to their kin in the United States and in Canada. The South American Germans from Russia had learned about Congregationalism in letters from relatives in the United States. In 1924 general missionary John Hoelzer, whilst in Argentina for a brief visit, organized six churches.

Australia

In 1977, most congregations of the Congregational Union of Australia merged with all Churches of the Methodist Church of Australasia and a majority of Churches of the Presbyterian Church of Australia to form the Uniting Church in Australia.

Those congregations that did not join the Uniting Church formed the Fellowship of Congregational Churches or continued as Presbyterians. Some more ecumenically minded Congregationalists left the Fellowship of Congregational Churches in 1995 and formed the Congregational Federation of Australia.

Bulgaria

Congregationalists (called "Evangelicals" in Bulgaria; the word "Protestant" is not used[9]) were among the first Protestant missionaries to the Ottoman Empire and to the Northwestern part of the European Ottoman Empire which is now Bulgaria, where their work to convert these Orthodox Christians was unhampered by the death penalty imposed by the Ottomans on Muslim converts to Christianity.[10] These missionaries were significant contributors to the Bulgarian National Revival movement. Today, Protestantism in Bulgaria represents the third largest religious group, behind Orthodox and Muslim. Missionaries from the United States first arrived in 1857–58, sent to Istanbul by the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM). The ABCFM was proposed in 1810 by the Congregationalist graduates of Williams College, MA, and was chartered in 1812 to support missions by Congregationalists, Presbyterian (1812–1870), Dutch-Reformed (1819–1857) and other denominational members.[11] The ABCFM focused its efforts on southern Bulgaria and the Methodist Church on the region north of the Balkan Mountains (Stara Planina, or "Old Mountains"). In 1857, Cyrus Hamlin and Charles Morse established three missionary centres in southern Bulgaria – in Odrin (Edirne, former capital city of the Ottoman Empire, in Turkey), Plovdiv and Stara Zagora. They were joined in 1859 by Russian-born naturalized America Frederic Flocken in 1859.[11] American Presbyterian Minister Elias Riggs commissioned, supported and edited the work of Bulgarian monk Neofit Rilski to create a Bible translations into Bulgarian which was then distributed widely in Bulgaria in 1871 and thereafter. This effort was supported by Congregationalist missionary Albert Long, Konstantin Fotinov, Hristodul Sechan-Nikolov and Petko Slaveikov.[11] Reportedly, 2,000 copies of the newly translated Bulgarian language New Testament were sold within the first two weeks.

Congregational churches were established in Bansko, Veliko Turnovo, and Svishtov between 1840 and 1878, followed by Sofia in 1899. By 1909, there were 19 Congregational churches, with a total congregation of 1,456 in southern Bulgaria offering normal Sunday services, Sunday schools for children, biblical instruction for adults; as well as women's groups and youth groups. Summer Bible schools were held annually from 1896 to 1948.[11]

Congregationalists led by Dr James F. Clarke opened Bulgaria's first Protestant primary school for boys in Plovdiv in 1860, followed three years later by a primary school for girls in Stara Zagora. In 1871 the two schools were moved to Samokov and merged as the American College, now considered the oldest American educational institution outside the US. In 1928, new facilities were constructed in Sofia, and the Samokov operation transferred to the American College of Sofia (ACS), now operated at a very high level by the Sofia American Schools, Inc.[12]

In 1874, a Bible College was opened in Ruse, Bulgaria for people wanting to become pastors. At the 1876 annual conference of missionaries, the beginning of organizational activity in the country was established. The evangelical churches of Bulgaria formed a united association in 1909.[11]

The missionaries played a significant role in assisting the Bulgarians throw off "the Turkish Yoke", which included publishing the magazine Zornitsa (Зорница, "Dawn"), founded in 1864 by the initiative of Riggs and Long.[13] Zornitsa became the most powerful and most widespread newspaper of the Bulgarian Renaissance.[11] A small roadside marker on Bulgarian Highway 19 in the Rila Mountains, close to Gradevo commemorates the support given the Bulgarian Resistance by these early Congregationalist missionaries.

On 3 September 1901 Congregationalist missionaries came to world attention in the Miss Stone Affair when missionary Ellen Maria Stone,[14] of Roxbury, Massachusetts, and her pregnant fellow missionary friend Macedonian-Bulgarian Katerina Stefanova–Tsilka, wife of an Albanian Protestant minister, were kidnapped while traveling between Bansko and Gorna Dzhumaya (now Blagoevgrad), by an Internal Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Organization detachment led by the voivoda Yane Sandanski and the sub-voivodas Hristo Chernopeev and Krǎstyo Asenov and ransomed to provide funds for revolutionary activities. Eventually, a heavy ransom (14,000 Ottoman lira (about US$62,000 at 1902 gold prices or $5 million at 2012 gold prices) raised by public subscription in the USA was paid on 18 January 1902 in Bansko and the hostages (now including a newborn baby) were released on 2 February near Strumica—a full five months after being kidnapped. Widely covered by the media at the time, the event has been often dubbed "America's first modern hostage crisis".

The Bulgarian royal house, of Catholic German extraction, was unsympathetic to the American inspired Protestants, and this mood became worse when Bulgaria sided with Germany in WWI and WWII.[15] Matters became much worse when the Bulgarian Communist Party took power in 1944. Like the Royal Family, it too saw Protestantism closely linked to the West and hence more politically dangerous than traditional Orthodox Christianity. This prompted repressive legislation in the form of "Regulations for the Organization and Administration of the Evangelical Churches in the People's Republic of Bulgaria" and resulted in the harshest government repression, possibly the worst in the entire Eastern Bloc, intended to extinguish Protestantism altogether. Mass arrests of pastors (and often their families), torture, long prison sentences (including four life sentences) and even disappearance were common. Similar tactics were used on parishioners. In fifteen highly publicized mock show-trials between 8 February and 8 March 1949, all the accused pastors confessed to a range of charges against them, including treason, spying (for both the US and Yugoslavia), black marketing, and various immoral acts. State appointed pastors were foist on surviving congregations. As late as the 1980s, imprisonment and exile were still employed to destroy the remaining Protestant churches. The Congregationalist magazine "Zornitsa" was banned; Bibles became unobtainable.[16] As a result, the number of Congregationalists is small and estimated by Paul Mojzes in 1982 to number about 5,000, in 20 churches. (Total Protestants in Bulgaria were estimated in 1965 to have been between 10,000 and 20,000.)[17] More recent estimates indicate enrollment in Protestant ("Evangelical" or "Gospel") churches of between 100,000 and 200,000,[18] presumably reflecting the success of more recent missionary efforts of evangelical groups. The United Church of Christ has been described as "the historic continuation of the Congregational churches".[19]

Canada

In Canada, the first foreign field, thirty-one churches that had been affiliated with the General Conference became part of the United Church of Canada when that denomination was founded in 1925 by the merger of the Canadian Congregationalist and Methodist churches, and two-thirds of the congregations of the Presbyterian Church in Canada. In 1988, a number of UCC congregations separated from the national church, which they felt was moving away theologically and in practice from Biblical Christianity. Many of the former UCC congregations banded together as the new Congregational Christian Churches in Canada.

Congregational Christian Churches in Canada

The Congregational Christian Churches in Canada (or 4Cs) is an evangelical, Protestant, Christian denomination, headquartered in Brantford, Ontario, and a member of the World Evangelical Congregational Fellowship. The name "congregational" generally describes its preferred organizational style, which promotes local church autonomy and ownership, while fostering fellowship and accountability between churches at the National level.

Ireland

The Congregational Union of Ireland was founded in 1829 and currently has around 26 member churches. In 1899 it absorbed the Irish Evangelical Society.[20] One of its ministers, Robert McEvoy, is secretary of an evangelical and creationist pressure group, the Caleb Foundation.

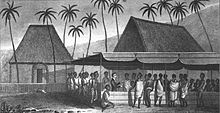

Samoa

The Congregational Christian Church of Samoa is one of the largest group of churches throughout the Pacific Region. It was founded in 1830 by the London Missionary Society missionary John Williams on the island of Savai'i in the village of Sapapali'i. As the church grew it established and continues to support theological colleges in Samoa and Fiji. There are over 100,000 members attending over 2,000 congregations throughout the world, most of which are located in Samoa, American Samoa, New Zealand, Australia and America. The Christian Congregational Church of Jamaica falls under the constitution of the Samoan Church.

Southern Africa

Congregational churches were brought to the Cape Colony by British settlers.

United Kingdom

In 1972, about three-quarters of English Congregational churches merged with the Presbyterian Church of England to form the United Reformed Church (URC). However, about 600 Congregational churches have continued in their historic independent tradition. Under the Act of Parliament that dealt with the financial and property issues arising from the merger between what had become by then the Congregational Church of England and Wales and the Presbyterian Church of England, certain assets were divided between the various parties.

In England, there are three main groups of continuing Congregationalists. These are the Congregational Federation, which has offices in Nottingham and Manchester, the Evangelical Fellowship of Congregational Churches, and about 100 Congregational churches that are loosely federated with other congregations in the Fellowship of Independent Evangelical Churches, or are unaffiliated.

In 1981, the United Reformed Church merged with the Re-formed Association of Churches of Christ and, in 2000, just over half of the churches in the Congregational Union of Scotland also joined the United Reformed Church. The remainder of Congregational churches in Scotland joined the Congregational Federation.

Wales traditionally is the part which has the largest share of Congregationalists among the population, most Congregationalists being members of Undeb yr Annibynwyr Cymraeg (the Union of Welsh Independents), which is particularly important in Carmarthenshire and Brecknockshire.

The London Missionary Society was effectively the world mission arm of British Congregationalists. It sponsored missionaries including Eric Liddell and David Livingstone. As thinking developed, particularly in the context of decolonisation, and churches wanted to recognise the gifts of people of the South, the London Missionary Society transformed into the Council for World Mission.

The current President of the Congregational Federation is Betty Bentham.[21]

United States

Early settlement of New England (1630–1640)

The Congregational tradition was brought to America in the 1630s by the Puritans—a Calvinistic group within the Church of England that desired to purify it of any remaining teachings and practices of the Roman Catholic Church.[22] As part of their reforms, Puritans desired to replace the Church of England's episcopal polity with another form of church government. Some English Puritans favored presbyterian polity (such as was utilized by the Church of Scotland), but those who founded the Massachusetts Bay Colony organized their churches along congregational lines.[23]

Developing the New England Way

According to historian James F. Cooper, Jr., Congregationalism helped imbue the political culture of Massachusetts with several important concepts: "adherence to fundamental or 'higher' laws, strict limitations upon all human authority, free consent, local self-government, and, especially, extensive lay participation."[24] However, congregational polity also meant the absence of any centralized church authority. The result was that at times the first generation of Congregationalists struggled to agree on common beliefs and practices. For example, specific rules on church membership and baptism requirements were still being debated into the late 1630s.[24]

To help achieve unity, Puritan clergy would often meet in conferences to discuss issues arising within the churches and to offer advice. Congregationalists also looked to the ministers of the First Church in Boston to set examples for other churches to follow. One of the most prominent of these ministers was John Cotton, considered by historians to be the "father of New England Congregationalism", who through his preaching helped to standardize Congregationalist practices. Because of these efforts at promoting unity, standardization of practices related to baptism, church discipline, and election of church officers was largely achieved by 1635.[25]

Within the first decade, the colonists developed a system in which each community organized a gathered church of believers (i.e. only those who were thought to be among the elect and could give an account of a conversion experience were admitted as members).[26] Every congregation was founded upon a church covenant, a written agreement signed by all members in which they agreed to uphold congregational principles, to be guided by sola scriptura in their decision making, and to submit to church discipline. The right of each congregation to elect its own officers and manage its own affairs was upheld.[27][28]

For church offices, Congregationalists imitated the model developed in Calvinist Geneva. There were two major offices: elder (or presbyter) and deacon. There were two types of elders. Ministers, whose responsibilities included preaching and administering the sacraments, were referred to as teaching elders. Prominent laymen would be elected as ruling elders. Ruling elders governed the church alongside teaching elders, and, while they could not administer the sacraments, they could preach. Ruling elders were chosen for life. The duties of deacons largely revolved around financial matters. Other than elders and deacons, congregations also elected messengers to represent them in synods (church councils) for the purpose of offering non-binding advisory opinions.[29]

The Puritans had created a society in which Congregationalism was the state church, its ministers were supported by tax payers, and only full church members could vote in elections.[30] By 1640, 18 churches had been gathered in Massachusetts.[31] In addition, Puritans established the Connecticut Colony in 1636 and New Haven Colony in 1637.[32] Altogether, there were 33 Congregational churches in New England.[33]

Antinomian Controversy

The major conflict during the settlement period was the Antinomian Controversy of 1636–1638. This crisis emerged over differences between those ministers who taught "preparationist" theology, which held that people could receive assurance of salvation through voluntary good works and sanctification, and the free grace theology preached by Cotton, who held that good works were not proof of election because no one could know for certain whether good works were motivated by hypocrisy. As early as 1635, Anne Hutchinson began holding meetings in her home and gathering a group of supporters that included the colony's governor, Henry Vane. These Hutchinsonians accused preparationist ministers of teaching legalism.[34]

By the fall of 1636, Hutchinson's support in Boston was growing. Eventually, she won over nearly the entire Boston congregation, which nearly censured its own pastor, John Wilson, for opposing the free grace position. Hutchinson also had the apparent support of Cotton and Boston's two ruling elders.[35] Outside of Boston, the elders of Massachusetts and the Connecticut and New Haven colonies unanimously rejected Hutchinson's teachings as Antinomianism. They finally prevailed upon Cotton to speak out against the errors of the Antinomians at a synod in September 1637. A civil trial was held in November in which Hutchinson was sentenced to banishment, and a church trial followed in March 1638 in which the Boston congregation switched sides and unanimously voted for Hutchinson's excommunication. This effectively ended the controversy.[36]

In the aftermath of the crisis, ministers realized the need for greater communication between churches and standardization of preaching. As a consequence, nonbinding ministerial conferences or "consociations" to discuss theological questions and address conflicts became more frequent in the following years.[37] A more substantial innovation was the implementation of the "third way of communion", a method of isolating a dissident or heretical church from neighboring churches. Members of an offending church would be unable to worship or receive the Lord's Supper in other churches.[38]

Defining Congregationalism (1640s)

In the 1640s, Congregationalists were under pressure to craft a formal statement of congregational church discipline. This was partly motivated by the need to reassure English Puritans about congregational government. It was feared that the English Parliament might intervene in New England's churches due to dissatisfaction with their admission policies.[39] It was also thought necessary to combat the threat of Presbyterianism at home. Conflict erupted in the churches at Newbury and Hingham when their pastors began introducing presbyterian governance.[40]

The Massachusetts General Court called for a synod to meet in Cambridge to craft such a statement. The Cambridge Platform was completed by the synod in 1648 and commended by the General Court as an accurate description of Congregational practice after the churches were given time to study the document, provide feedback, and finally ratify it. While the Platform was legally nonbinding and intended only to be descriptive, it soon became regarded by ministers and lay people alike as the religious constitution of Massachusetts, guaranteeing the rights of church officers and members.[41]

17th century beliefs

In the 17th century, Congregationalists were Puritans who still identified themselves as members of the Church of England.[27] As Calvinistic Protestants, Congregational churches shared common beliefs with other Reformed churches, such as sola scriptura,[42] unconditional election,[43] covenant theology,[44] Reformed worship, Reformed baptismal theology, and Reformed views on the Lord's Supper. The Savoy Declaration, a modification of the Westminster Confession of Faith, was adopted as a Congregationalist confessional statement in Massachusetts in 1680 and in Connecticut in 1708.[45]

Congregationalists were distinguished from other Reformed churches by their form of church governance. Other Reformed churches had adopted a presbyterian polity that placed power in the hands of synods of elders rather than with individual congregations. Another difference was the Congregational belief that churches should be "churches of saints". To ensure that only regenerated persons were admitted into the church, Congregationalists required prospective members to undergo an admissions test consisting of giving testimony of one's conversion experience.[46] While Congregational churches practiced infant baptism, baptized persons were not considered full members until they could provide the congregation with a satisfactory conversion narrative.[44]

18th century

Centralizing forces made the Congregational church even more powerful and more conservative. The Saybrook Platform was a new constitution for the Congregational church in Connecticut in 1708. Religious and civic leaders in Connecticut around 1700 were distressed by the colony-wide decline in personal religious piety and in church discipline. The colonial legislature sponsored a meeting in Saybrook. It drafted articles which rejected extreme localism or Congregationalism that had been inherited from England and replaced it with a system similar to what the Presbyterians had. The Congregational church was now to be led by local ministerial associations and consociations composed of ministers and lay leaders from a specific geographical area. Instead of the congregation from each local church selecting its minister, the associations now had the responsibility to examine candidates for the ministry, and to oversee a behavior of the ministers. The consociations (where laymen were powerless) could impose discipline on specific churches and judge disputes that arose. The result was a centralization of power that bothered many local church activists. However, the official associations responded by disfellowshipping churches that refused to comply. The system survived to the mid-nineteenth century, well after Congregationalism was officially disestablished in the state of Connecticut. The Platform marked a conservative counter-revolution against a non-conformist tide which had begun with the Halfway Covenant and would later culminate in the Great Awakening in the 1750s.[47][48] Similar proposals for more centralized clerical control of local churches were defeated in Massachusetts.[49]

In Boston, The Congregational Library and Archives holds numerous collections all across New England. As an example, they hold every one of the Richard Taylor surveys which showcase the amount of people and churches across the entire New England area.[50]

The history of Congregational churches is closely intertwined with that of American Presbyterianism, especially in New England where an arrangement made Yankee Congregationalists who moved west join Presbyterian churches.

Some of the first colleges and universities in America, including Harvard, Yale, Dartmouth, Williams, Bowdoin, Middlebury, and Amherst, all were founded by the Congregationalists, as were later Carleton, Grinnell, Oberlin, Beloit, Pomona, Rollins and Colorado College.

Unitarianism

Without higher courts to ensure doctrinal uniformity among the congregations, Congregationalists have been more diverse than other Reformed churches. Despite the efforts of Calvinists to maintain the dominance of their system, some Congregational churches, especially in the older settlements of New England, gradually developed leanings toward Arminianism, Unitarianism, Deism, and Transcendentalism.

By the 1750s, several Congregational preachers were teaching the possibility of universal salvation, an issue that caused considerable conflict among its adherents on the one side and hard-line Calvinists and sympathizers of the First Great Awakening on the other. In another strain of change, the first church in the United States with an openly Unitarian theology, the belief in the single personality of God, was established in Boston, Massachusetts in 1785 (in a former Anglican parish, King's Chapel). By 1800, all but one Congregational church in Boston had Unitarian preachers teaching the strict unity of God, the subordinate nature of Christ, and salvation by character.

Harvard University, founded by Congregationalists, became a center of Unitarian training. Prompted by a controversy over an appointment in the theology school at Harvard, in 1825 the Unitarian churches separated from Congregationalism. Most of the Unitarian "descendants" hold membership in the Unitarian Universalist Association, founded in the 1960s by a merger with the theologically similar Universalists. This group had dissented from Calvinist orthodoxy on the basis of their belief that all persons could find salvation (as opposed to the Calvinist idea of double predestination, excluding some from salvation.)

Congregational churches were at the same time the first example of the American theocratic ideal[51] and also the seedbed from which American liberal religion and society arose. Many Congregationalists in the several successor denominations to the original tradition consider themselves to be Reformed first, whether of traditional or neo-orthodox persuasion.

20th century

In 1931 the National Council of the Congregational Churches of the United States and the General Convention of the Christian Church, a body from the Restoration Movement tradition of the early 19th century, merged to form the Congregational Christian Churches. The Congregationalists were used to a more formal, less evangelistic form of worship than Christian Church members, who mostly came from rural areas of the South and the Midwest. Both groups, however, held to local autonomy and eschewed binding creedal authority.

In the early 20th century some Congregational (later Congregational Christian) churches took exception to the beginnings of a growth of regional or national authority in bodies outside the local church, such as mission societies, national committees, and state conferences. Some congregations opposed liberalizing influences that appeared to mitigate traditional views of sin and corollary doctrines such as the substitutionary atonement of Jesus. In 1948, some adherents of these two streams of thought (mainly the latter one) started a new fellowship, the Conservative Congregational Christian Conference (CCCC). It was the first major fellowship to organize outside of the mainstream Congregational body since 1825 when the Unitarians formally founded their own body.

In 1957, the General Council of Congregational Christian Churches in the U.S. merged with the Evangelical and Reformed Church to form the United Church of Christ. About 90% of the CC congregations affiliated with the General Council joined the United Church of Christ. Some churches abstained from the merger while others voted it down. Most of the latter congregations became members of either the CCCC (mentioned above) or the National Association of Congregational Christian Churches. The latter was formed by churches and people who objected to the UCC merger because of concerns that the new national church and its regional bodies represented extra-congregational authorities that would interfere with a congregation's right to govern itself. Thus, the NACCC includes congregations of a variety of theological positions. Still other congregations chose not to affiliate with any particular association of churches, or only with regional or local ones.

See also

- Arminianism

- Fellowship of Independent Evangelical Churches

- List of Congregational churches

- Continental Reformed church

References

Citations

- ^ Browne, Robert, A booke which sheweth the life and manners of all true Christians and howe unlike they are unto Turkes and Papistes, and heathen folke. 1582

- ^ "Pewforum: Christianity (2010)" (PDF). Retrieved 2014-05-14.

- ^ [1] [dead link]

- ^ "Scottish Congregationalism, Congregational History, Alan Paterson | Hamilton United Reformed Church". Hamilton.urc.org.uk. Retrieved 2017-05-24.

- ^ Jefferson, Charles Edward (1910). Congregationalism. Boston: The Pilgrim Press. p. 22.

- ^ Jefferson 1910, p. 25. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFJefferson1910 (help)

- ^ "VHD". Vhd.heritage.vic.gov.au. Retrieved 2017-05-24.

- ^ "Google Maps". Maps.google.com. Retrieved 2017-05-24.

- ^ Mojzes, Paul; Shenk, Gerald (1992). "Protestantism in Bulgaria and Yugoslavia Since 1945". Protestantism and Politics in East Europe and Russia, Ramet, Sabrina Petra, ed., p. 209. Duke University Press. Retrieved 27 December 2012.

- ^ Mojzes, Paul; Shenk, Gerald (1992). "Protestantism in Bulgaria and Yugoslavia Since 1945". Protestantism and Politics in East Europe and Russia, Ramet, Sabrina Petra, ed., p. 210. Duke University Press. Retrieved 27 December 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f Vassileva, Anastasia (August 8, 2008). "A history of protestantism in Bulgaria". The Sofia Echo. Retrieved 27 December 2012.

- ^ American College of Sofia (2010). "History of American College of Sofia". American College of Sofia. Retrieved 27 December 2012.

- ^ The Evangelical Churches in Bulgaria (2012). "History". Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- ^ Chelsey, Historical Society. "Ellen Maria Stone". Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- ^ Mojzes, Paul; Shenk, Gerald (1992). "Protestantism in Bulgaria and Yugoslavia Since 1945". Protestantism and Politics in East Europe and Russia, Ramet, Sabrina Petra, ed., p. 212. Duke University Press. Retrieved 27 December 2012.

- ^ Mojzes, Paul; Shenk, Gerald (1992). "Protestantism in Bulgaria and Yugoslavia Since 1945". In Ramet, Sabrina Petra (ed.). Protestantism and Politics in East Europe and Russia. Duke University Press. pp. 214–215. Retrieved 27 December 2012.

- ^ Mojzes and Shenk, pp. 209–236, 383.

- ^ Altanov, Velislav (c. 2012). Religious Revitalization Among Bulgarians During and After the Communist Time. Sent in private email communication from Dr. Paul Mojzes. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- ^ Queen, Edward L.; Prothero, Stephen R.; Shattuck, Gardiner H. (1 January 2009). Encyclopedia of American Religious History. Infobase Publishing. p. 818.

- ^ [2][dead link]

- ^ [3][dead link]

- ^ Bremer 2009, pp. 2–3.

- ^ Bremer 2009, pp. 9, 20.

- ^ a b Cooper 1999, p. 18.

- ^ Cooper 1999, pp. 20–22.

- ^ Cooper 1999, p. 17,19: "Likewise, though it had been practiced in New England for several years, they reaffirmed from First Corinthians that 'churches should be churches of saints' and must therefore require of members a test of grace, or conversion."

- ^ a b Bremer 2009, p. 20.

- ^ Cooper 1999, p. 13.

- ^ Cooper 1999, pp. 24, 26.

- ^ Walker 1894, pp. 114, 221.

- ^ Cooper 1999, pp. 14, 33.

- ^ Bremer 2009, pp. 21–22.

- ^ Walker 1894, p. 116.

- ^ Cooper 1999, pp. 47–49.

- ^ Cooper 1999, p. 47.

- ^ Cooper 1999, pp. 50–52.

- ^ Cooper 1999, pp. 55–56.

- ^ Cooper 1999, p. 57.

- ^ Cooper 1999, p. 76.

- ^ Cooper 1999, pp. 69–70.

- ^ Cooper 1999, p. 79–84.

- ^ Cooper 1999, p. 14.

- ^ Walker 1894, p. 215.

- ^ a b Campbell 2013.

- ^ Youngs 1998, p. 52.

- ^ Cooper 1999, p. 17.

- ^ Williston Walker, The Creeds and Platforms of Congregationalism (1960)

- ^ Bushman (1970). From Puritan to Yankee: Character and the Social Order in Connecticut, 1690-1765. p. 151.

- ^ Patricia U. Bonomi (1986). Under the Cope of Heaven : Religion, Society, and Politics in Colonial America. Oxford University Press. pp. 62–64.

- ^ Richard H. Taylor. Churches of Christ of the Congregational Way in New England. ISBN 9780962248603. Retrieved 2017-05-24.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ M. Schmidt, Pilgerväter, in Die Religion in Geschichte und Gegenwart, 3. Auflage, Band V (1961), Tübingen (Germany), col. 384

Bibliography

- Bremer, Francis J. (2009). Puritanism: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199740871.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Campbell, Donna M. (2013). "Puritanism in New England". wsu.edu. Retrieved June 4, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Cooper, James F., Jr. (1999). Tenacious of Their Liberties: The Congregationalists in Colonial Massachusetts. Religion in America. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195152875.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Jefferson, Charles Edward (1910). Congregationalism. Boston: The Pilgrim Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Walker, Williston (1894). A History of the Congregational Churches in the United States. American Church History. Vol. 3. New York: The Christian Literature Company.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Youngs, J. William T. (1998). The Congregationalists. Denominations in America. Vol. 4 (Student ed.). Westport, Connecticut: Praeger. ISBN 9780275964412.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Further reading

United States

- Swift, David Everett. “Conservative versus Progressive Orthodoxy in Latter Nineteenth Century Congregationalism.” Church History 16#1 (March, 1947): 22-31.

- Von Rohr, John. The Shaping of American Congregationalism 1620-1957 (1990).

- Walker, Williston. “Changes in Theology Among American Congregationalists.” American Journal of Theology 10#2 (April 1906): 204-218.

- Walker, Williston. The Creeds and Platforms of Congregationalism. 3rd ed. Boston, MA: Pilgrim Press, 1960.

- Walker, Williston. “Recent Tendencies in the Congregational Churches.” The American Journal of Theology 24#1 (January, 1920): 1-18.

England

- Argent, Alan. The Transformation of Congregationalism 1900-2000 (Nottingham: Congregational Federation, 2013).

- Hooper, Thomas. The Story of English Congregationalism (1907)[1]

- Ottewill, Roger Martin. "Faith and good works: congregationalism in Edwardian Hampshire 1901-1914" (PhD. Diss. University of Birmingham, 2015) Bibliography pp 389-417.[2]

- Rimmington, Gerald. “Congregationalism in Rural Leicestershire and Rutland 1863-1914.” Midland History 30, no.1 (2006): 91-104.

- Rimmington, Gerald. “Congregationalism and Society in Leicester 1872-1914.” Local Historian 37#1 (2007): 29-44.

- Thompson, David. Nonconformity in the Nineteenth Century (1972).

- Thompson, David M. The Decline of Congregationalism in the Twentieth-Century. (London: The Congregational Memorial Hall Trust, 2002).

Older Works by John Waddington

- Congregational Martyrs. London, 1861, intended to form part of a series of 'Historical Papers,' which, however, were not continued; 2nd ed. 1861

- Congregational Church History from the Reformation to 1662, London, 1862, awarded the bicentenary prize offered by the Congregational Union

- Surrey Congregational History, London, 1866, in which he dealt more particularly with the records of his own congregation.

- Congregational History, 5 vols., London, 1869–1880

- McConnell, Michael W. "Establishment and Disestablishment at the Founding, Part I: Establishment of Religion" William and Mary Law Review, Vol. 44, 2003, pp. 2105

- ^ Thomas Hooper (Minister of Streatham Congregational Church.) (2008-08-27). The Story of English Congregationalism. Retrieved 2017-05-24.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ ROGER MARTIN OTTEWILL. "FAITH AND GOOD WORKS: CONGREGATIONALISM IN EDWARDIAN HAMPSHIRE 1901-1914" (PDF). Etheses.bham.ac.uk. Retrieved 2017-05-24.