Constitution of the Roman Republic

|

|---|

| Periods |

|

| Constitution |

| Political institutions |

| Assemblies |

| Ordinary magistrates |

| Extraordinary magistrates |

| Public law |

| Senatus consultum ultimum |

| Titles and honours |

The Constitution of the Roman Republic or mos maiorum (Latin for "customs of the ancestors") was an unwritten set of guidelines and principles passed down mainly through precedent.[1] The constitution was largely unwritten, uncodified, and constantly evolving. Rather than creating a government that was primarily a democracy (as was ancient Athens), an aristocracy (as was ancient Sparta), or a monarchy (as was Rome before and after the republic), the Roman constitution mixed these three elements, thus creating three separate branches of government. The democratic element took the form of the legislative assemblies, the aristocratic element took the form of the senate, and the monarchical element took the form of the many term limited executive magistrates. The constitutional harmony relied on a careful balance between these three branches.

The ultimate source of sovereignty in this ancient republic, as in modern republics, was the demos (people). The People of Rome would gather into legislative assemblies to pass laws and to elect executive magistrates. Election to a magisterial office resulted in automatic membership in the senate (for life, unless impeached). The senate managed the day-to-day affairs in Rome, while senators presided over the courts. Executive magistrates enforced the law, and presided over the senate and the legislative assemblies. A complex set of checks and balances developed between these three branches, so as to minimize the risk of tyranny and corruption, and to maximize the likelihood of good government.

However, the separation of powers between these three branches of government was not absolute. Also, there was the frequent usage of several constitutional devices that were out of harmony with the genius of the Roman constitution. The constitutional balance was first disrupted by (and towards) the democracy under the tribunates of Tiberius and Gaius Gracchus. Forty years later, in response to the constitutional crisis that had been created by the two Gracchi tribunes, the dictator Lucius Cornelius Sulla exacerbated the problem by violently shifting the imbalance from the democracy towards the aristocracy. Over the next forty years, this constitutional imbalance continued to deteriorate, as it shifted towards an increasingly militaristic executive. This constitutional crisis ultimately led to the collapse of the Roman Republic and its subversion into a much more autocratic form of government which would later be called Roman Empire.

Constitutional history

The constitutional history of the Roman Republic can be divided into five phases. The first phase began with the revolution which overthrew the monarchy in 510 BC, while the final phase ended in 27 BC, with the revolution which overthrew the Roman Republic. Throughout the history of the republic, the constitutional evolution was driven by the struggle between the aristocracy and the ordinary citizens.

Patrician era (509-367 BC)

According to legend, the last king was overthrown in 510 BC. While this story is nothing more than a legend which later Romans created in order to explain their past, it is likely that Rome had been ruled by a series of kings.[2] The historical monarchy, as the legends suggest, was probably overthrown quickly; while the most important constitutional change which occurred immediately after the overthrow of the monarchy probably concerned the chief executive. After 510 BC two consuls were elected by the citizens for an annual term,[2] each consul would check his colleague, while their limited term in office would open them up to prosecution if they abused the powers of their office. In the immediate aftermath of the revolution, the senate and the assemblies were as powerless as they had been under the monarchy.

In the year 494 BC, the plebeians seceded to the Aventine hill, and demanded the right to elect their own officials.[3] The patricians duly capitulated, and the plebeians ended their secession. The plebeians called these new officials "plebeian tribunes". The tribunes were first given two assistants, called "plebeian aediles", then granted the power to veto the senate, and then allowed to preside over the Plebeian Council. In 443 BC, the censorship was created,[4] and in 367 BC, plebeians were allowed to stand for the consulship. The opening of the consulship to the plebeian class implicitly opened both the censorship as well as the dictatorship to plebeians.[5] In 366 BC, in an effort by the patricians to reassert their influence over the magisterial offices, two new offices were created: the praetorship and the curule aedileship.[4] It wasn't long before even these offices began being held by plebeians, as the first plebeian praetor was elected in 337 BC.

Conflict of the Orders (367-287 BC)

Template:Roman Constitution Sidebar These years saw several disturbing trends begin to immerge, such as the increasing closeness between the tribunes and the senators.[6] The senate began giving tribunes a great deal of power, such as an official recognition of their right to veto. The tribunes, perhaps unsurprisingly, therefore began to feel indebted to the senate.[6] As the tribunes and the senators grew closer, plebeian senators were often able to secure the tribunate for members of their own families.[7] In addition, in the year 342 BC, two significant laws were passed: one made it illegal to hold more than one office at any given point in time, while the other required an interval of ten years to pass before any magistrate could seek reelection to any office.[8] These two laws introduced a new weakness into the constitution, which would eventually begin to pave the way for the Roman Empire.

Around the middle of the fourth century BC, the Plebeian Council enacted the "Ovinian Law"[9] which transferred, from the consuls to the censors, the power to appoint new senators. This law also required the censors to appoint any newly-elected magistrate to the senate.[9] By this point, plebeians were already holding a significant number of magisterial offices, so the number of plebeian senators probably increased quickly.[10] By this point, however, the closeness between the tribunes and the senate had facilitated the creation of a new plebeian aristocracy: most plebeians elected to political office were by now coming from one of these plebeian families.[10] This new plebeian aristocracy soon merged with the old patrician aristocracy, creating a combined "patricio-plebeian" aristocracy.[10] The old aristocracy existed through the force of law, because only patricians had been allowed to stand for high office. Now, however, the new aristocracy existed due to the organization of society, and as such, this order could only be overthrown through a revolution.[11]

In 287 BC, the plebeians seceded to the Janiculum hill. To end the secession, a law (the "Hortensian Law") was passed, which ended the requirement that the patrician senators consent before a bill could be brought before the Plebeian Council for a vote.[12] This was not the first law to require that an act of the Plebeian Council have the full force of law:[13] the Plebeian Council acquired this power during a modification to the original Valerian law in 449 BC.[13] The ultimate significance of this law was in the fact that it robbed the patricians of their final weapon over the plebeians, and thus resulted in plebeian senators having the same rights as patrician senators. The result was that the ultimate control over the state fell, not onto the shoulders of democracy, but onto the shoulders of the new patricio-plebeian aristocracy.[14]

Supremacy of the new nobility (287-133 BC)

The great accomplishment of the Hortensian Law was in that it deprived the patricians of their last weapon over the plebeians, thus resolving the last great political question of the earlier era. As such, no important political changes occurred between 287 BC and 133 BC.[15] The critical laws of this era were still enacted by the senate.[16] In effect, the democracy was satisfied with the possession of power, but did not care to actually use it. The senate was supreme during this era because the era was dominated by questions of foreign and military policy,[17] as this era was the most militarily active era of the Roman Republic.

The final decades of this era saw a worsening economic situation for many plebeians,[18] as the long military campaigns had forced citizens to leave their farms to fight, only to return to farms that had fallen into disrepair. The landed aristocracy began buying bankrupted farms at discounted prices, and staffed these farms with cheap slaves. As commodity prices fell, many farmers could no longer operate their farms at a profit, and as such went bankrupt.[18] Masses of unemployed plebeians soon began to flood into Rome, and thus into the ranks of the legislative assemblies, where their economic status usually led them to vote for the candidate who offered the most for them. A new culture of dependency was emerging, which would look to any populist leader for relief.[19]

From the Gracchi to Caesar (133-49 BC)

The prior era saw great military successes, and great economic failures, while the patriotism of the plebeians had kept them from seeking any new reforms. Now, the military situation had stabilized, and fewer soldiers were needed. This, in conjunction with the new slaves that were being imported from abroad, inflamed the unemployment situation further. The flood of unemployed citizens to Rome had made the assemblies quite populist, and resulted in an increasingly aggressive democracy.

Gracchi tribunates

Tiberius Gracchus, who had been elected plebeian tribune on a populist platform in 133 BC, attempted to enact a law which would have limited the amount of land that any individual could own. The people were strongly supportive of Tiberius, while the aristocrats, who stood to lose an enormous amount of money, were bitterly opposed to the proposal. Tiberius submitted his law to the Plebeian Council, but the law was vetoed by an aristocratic tribune named Marcus Octavius, who had been set up by the senate to obstruct Triberius' proposed law. In an attempt to force Octavius to capitulate, Tiberius tried to turn the mob against Octavius by enacting a blanket veto over all governmental functions, which, in effect, shut down the entire city and precipitated rioting. When that failed, Tiberius violently removed Octavius, and then used the Plebeian Council to impeach him. The theory, that a representative of the people ceases to be one when he acts against the wishes of the people, was repugnant to the genius of Roman constitutional theory.[20] If carried to its logical end, this theory would remove all constitutional restraints on the popular will, and put the state under the absolute control of a temporary popular majority.[20] His law would be enacted, but Tiberius, whose sacrilege set the example that the dictator Julius Caesar would follow less than a century later, was murdered when he stood for reelection to the tribunate.

Tiberius' brother Gaius was elected plebeian tribune in 123 BC, also on a platform of economic populism. Gaius Gracchus' ultimate goal was to weaken the senate and to strengthen the democratic forces.[21] In the past, for example, the senate would eliminate political rivals either by establishing special judicial commissions or by passing a senatus consultum ultimum ("ultimate decree of the senate"). Both devices would allow the senate to bypass the ordinary due process rights that all citizens had.[22] Gaius outlawed the judicial commissions, and declared the senatus consultum ultimum to be unconstitutional. Gaius then proposed a law which would grant citizenship rights to Rome's Italian allies, but the selfish democracy, who jealously guarded their privileged rights as Roman citizens, finally deserted him.[22] He stood for election to a third term in 121 BC, but was defeated and then murdered. The democracy, however, had finally realized how weak the senate had become, and began asserting themselves so aggressively that they terminally disrupted the constitutional balance (between the people and the senate) that had ensured the stability of the constitutional system for the past four hundred years.[22]

Party politics and the constitutional reforms of Sulla

The consul of 88 BC, Lucius Cornelius Sulla, took an army to fight king Mithridates of Pontus. But a former consul and bitter opponent of Sulla, Gaius Marius, had a tribune revoke Sulla's command of the war. While Marius was a member of the democratic ("populare") party, Sulla was a member of the aristocratic ("optimate") party. Sulla, outraged by the revokation of his command of the war, brought his army back to Italy, and became the first Roman general in history to march on Rome. Sulla had become so angry at Marius' tribune that he developed a lasting anger at the tribunes in particular, and the power of the democracy in general. While in Rome, he murdered many of Marius' supporters, and then passed a law that was intended to permanently weaken the tribunate.[23] He then returned to his war against Mithridates, leaving a power vaccum that allowed the populares under Marius and Lucius Cornelius Cinna to take back control of the city.

The populare record was not one to be proud of.[23] They had first elected Marius consul before he was even twenty years old, and then reelected him several times without observing the required ten year interval. They also transgressed democracy by advancing un-elected individuals to magisterial office, and by substituting magisterial edicts for popular legislation.[24] In 83 BC, after making peace with Mithridates, Sulla returned to Rome, violently captured the city again, and then slaughtered Marius' remaining supporters. In 82 BC, Sulla made himself dictator, and then used his status as dictator to pass a series of constitutional reforms.

Sulla, who had observed the violent results of radical populare reforms (in particular those under Marius and Cinna), was naturally conservative, and as such, his conservatism was more reactionary than it was visionary.[24] To weaken the threat that the democracy presented to constitutional stability, Sulla sought to strengthen the aristocracy, and thus the senate.[24] As such, Sulla retained his earlier reforms, which had required senate approval before any bill could be submitted to the Plebeian Council, and which had also restored the aristrocratic Servian organization to the Century Assembly.[23] Through the reforms to the Plebeian Council, the democracy was weakened, and the tribunes lost the power to initiate legislation. Sulla then prohibited ex-tribunes from ever holding any other office. Now, ambitious individuals would not seek election to the tribunate, since such an election would, in effect, end their political career.[25] Sulla then weakened the magisterial offices by increasing the number of magistrates who would be elected in any given year,[24] which diluted the power of each magistrate, and increased the likelihood of vetoes between magistrates. Since the popular assemblies elected all magistrates, this particular reform further weakened the power of the democracy. Sulla further increased the power of the senators by transferring control of the courts from the knights (whom had held control since the Gracchi reforms) to the senators.[25]

To reduce the risk that a future leader would amass too much power (as Sulla himself had done), he established definitively the requirement that any individual wait for ten years before being reelected to any office. Sulla was then the first to formaly codify the cursus honorum,[25] which required an individual to reach a certain age and level of experience before running for any particular office. Sulla then established a system where all consuls and praetors would serve in Rome during their year in office, and then command a provincial army as governor for the year after they left office.[25]

In 80 BC, Sulla resigned his dictatorship, served one last term as consul, and then died in 78 BC. While he thought that he had firmly established aristocratic rule, his own career had illustrated the fatal weakness in the constitution: that it was the army, and not the senate, which dictated the fortunes of the state.[26]

First Triumvirate

In 77 BC, the senate sent one of Sulla's former lieutenants, Gnaeus Pompey Magnus ("Pompey the Great"), to put down an uprising in Spain. By 71 BC, Pompey returned to Rome after having completed his mission. Around the same time, another of Sulla's former lieutenants, Marcus Licinius Crassus, had just put down a slave revolt in Italy. Upon their return, Pompey and Crassus found the populare party fiercely attacking Sulla's constitution.[27] They attempted to forge an agreement with the populare party: If both Pompey and Crassus were elected consul in 70 BC, they would dismantle the more obnoxious components of Sulla's constitution.[28] The two were soon elected, and quickly followed through on their promise.[28] Before long, Pompey was sent abroad again, this time to put down the threat posed by Mediterranean pirates, and then to find glory in the east.

In 62 BC, Pompey returned victorious from Asia, but found the senate refusing to ratify the arrangements that he had made. Thus, when Julius Caesar returned from his governorship in Spain in 61 BC, he found it easy to make an arrangement with Pompey.[29] Caesar and Pompey, along with Crassus, established a private agreement, known as the First Triumvirate. Under the agreement, Pompey's arrangements were to be ratified, Crassus was to be promised a future consulship, and Caesar was to be promised the consulship in 59 BC, and then the governorship of Gaul immediately afterwards.[29]

Caesar became consul in 59 BC, along with Marcus Calpurnius Bibulus as his colleague.[29] Caesar submitted the laws that he had promised Pompey to the assemblies, but Bibulus, an extreme aristocrat, attempted to obstruct the enactment of these laws. Caesar used violent means to ensure their passage, which so intimidated Bibulus that he spent the rest of the year in his house issuing declarations of bad omens.[29] Caesar, now unobstructed, continued to dominate the state for the rest of the year. When his term ended, he took four legions up north, and began a five year term as governor of three provinces.

While Caesar was gone, Pompey and Crassus proved themselves to be as incompetent as Caesar had hoped.[30] Beginning in the summer of 54 BC, a wave of political corruption and violence swept Rome.[31] Eventually, the triumvirate was renewed: Pompey and Crassus were promised the consulship in 55 BC, and Caesar's term as governor was extended for five years. While Caesar had married his daughter, Julia, to Pompey to solidify the arrangement, Julia eventually died in childbirth. This, in conjunction with Crassus' death in battle in 53 BC, severed the last remaining bound between Pompey and Caesar.

On January 1 of 49 BC, the senate passed a resolution which declared that if Caesar did not lay down his arms by July of that year, he would be considered an enemy of the republic.[32] On January 7 of 49 BC, the senate passed a senatus consultum ultimum, which vested Pompey with dictatorial powers. In response, Caesar quickly crossed the Rubicon with his veteran army, and marched towards Rome. Caesar's rapid advance forced Pompey, the consuls and the senate to abandon Rome for Greece, and allowed Caesar to enter the city unopposed.

Senate

The senate's auctoritas ("authority") derived from its esteem and prestige,[33] which was based on precedent, custom, and the high caliber and prestige of the senators.[34] As the senate was the only political institution that was eternal and continuous (compared to, for example, the consulship, which expired at the end of every annual term), to only it belonged the dignity of the antique traditions.[33]

The focus of the Roman senate was directed towards foreign policy.[35] While its role in military conflict was officially advisory, the senate was ultimately the force that oversaw those conflicts. While the consuls would have formal command over the armies, the consular command of those armies would be directed by the senate.

The senate also managed civil administration within the city. For example, only the senate could authorize the appropriation of public monies from the treasury.[35] In addition, the senate would try individuals accused of political crimes (such as treason).[35]

The senate passed decrees, which were called senatus consultum. This was officially "advice" from the senate to a magistrate. In practice, however, these decrees were usually obeyed by the magistrates.[36] If a senatus consultum conflicted with a lex ("law") that was passed by a popular assembly, the lex would override the senatus consultum.[37]

In addition, the senate was as much a religious institution, as it was a political institution. As such, it operated while under various religious restrictions. Every senate meeting would occur in an inaugurated space (a templum). Before any meeting could begin, a sacrifice to the gods would be made, and the auspices would be taken in order to determine whether that particular senate meeting held favor with the gods.[38]

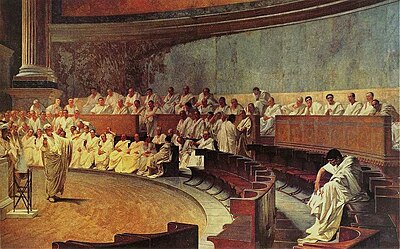

Senate procedure

The rules and procedures of the Roman senate were both complex and ancient. Many of these rules and procedures originated in the early years of the republic, and were upheld over the centuries.

Meetings could take place either inside or outside of the formal boundary of the city (the pomerium). Meetings usually began at dawn, and would be presided over by a consul (or by a praetor if the consuls were not in the city).[39] The presiding magistrate would often begin each meeting with a speech,[40] and would then refer the issue to the senators, who would discuss the matter by order of seniority.[41] Unimportant matters could be voted on by a voice vote or by a show of hands. However, important votes resulted in a physical division of the house,[41] with senators voting by taking a place on either side of the chamber. Since all meetings had to end by nightfall,[36] a senator could talk a proposal to death (a filibuster or diem consumere), if they could keep the debate going until nightfall.[40]

There was an absolute right to free speech in the senate.[41] During senate sessions, senators had several ways in which they could influence (or frustrate) a presiding magistrate. When a presiding magistrate was proposing a motion, the senators could call consule (consult). This would require that magistrate to ask for the opinions of the senators. The cry of numera would require a count of the senators present (similar to a modern "quorum call"). Any vote would always be between a proposal and its negative.[42]

Any proposed motion could be vetoed by a tribune. Any act that had been vetoed would be recorded in the annals as a senatus auctoritas. Any motion that was passed and not vetoed would be turned into a final senatus consultum. Each senatus auctoritas and each senatus consultum would be transcribed into a document by the presiding magistrate, and then deposited into the building that housed the treasury.[36]

Legislative Assemblies

There were two types of Roman assembly. The first was the comitia ("committee"). [43] Comitiae were assemblies of all citizens (populus Romanus, or "People of Rome").[44] Comitiae were used for official purposes, such as for the enactment of laws. Acts of a comitia applied to all of the members of that comitia (and thus, of all of the People of Rome).

The second type of assembly was the concilium ("council"). Concilia were forums (fora) where specific groups of people would meet for an official purpose (such as to enact a law).[44] For example, the concilium plebis (“Plebeian Council “) would be a concilium where plebeians would meet.[45] Acts of a concilium would only apply to the members of that concilium. This is why, for example, acts of the plebeian concilium ("plebiscites") originally applied only to plebeians.

In contrast to the comitia and the concilium, a conventio ("convention") was an unofficial forum for communication. This was simply a forum where Romans would meet for specific unofficial purposes, such as to hear a political speech.[43] Ordinary citizens could only speak before a conventio (and not before a comitia or concilium).[46] These conventiones were simply meetings, rather than any mechanism through which to make legal decisions. As such, the voters would first assemble into conventiones to hear speeches, and then into comitiae or concilia to actually vote. [47]

Before any session could begin, the auspices (a search for omens from the Gods) would have to be taken. On the day of the assembly, the electors would assemble into a conventio ("convention").[47] While in the conventio, speeches would be heard, and any bill would be read to the assembly by a herald. The electors would then be told to assemble into their respective centuries, tribes, or curiae. Ballots (either a pebble or a written ballot) would be collected, counted, and the results would be reported to the presiding magistrate. Only the block of voters (century, tribe or curiae), and not the individual electors, would cast the formal vote (one vote per block, regardless of the total number of electors in each block) before the assembly.[48] The majority of votes in any century, tribe or curiae would decide how that century, tribe, or curiae voted.

Assembly of the Curiae

During the first decades of the republic, the People of Rome were organized into thirty curiae.[49][50][51] The curiae were organized on the basis of the clans (ethnic kinships).[52] During this time, neither centuries nor tribes were used for political purposes. The curiae would assemble for legislative, electoral and judicial purposes into an assembly of curiae called the Curiate Assembly ("Comitia Curiata").

During the first decades of the republic, consuls would preside over the Curiate Assembly.[53] Shortly after the founding of the republic, the powers of the Curiate Assembly were transferred to the Century Assembly and the Tribal Assembly.[50] The now-obsolete Curiate Assembly would still be presided over by a consul,[39] while any law passed by it could be vetoed by a tribune. In addition, the activity of the assembly could be interfered with by the auspices.[51]

After it had fallen into disuse, the primary legislative role of the Curiate Assembly was to pass the annual lex curiata de imperio. Theoretically, this was necessary to ratify the election of consuls and praetors by granting them imperium powers. In practice, however, this may have been a ceremonial (and unnecessary) task.[51]

The curiae were organized on the basis of clan (or ethnic kinship).[52] Therefore, long after the Curiate Assembly had lost most of its political powers, it retained jurisdiction over clan matters.[53] Under the presidency of the Pontifex Maximus,[50] it would witness wills and ratify adoptions.[50] It would also inaugurate certain priests, and transfer citizens from patrician class to plebeian class.

Assembly of the Centuries

During the years of the Roman Republic, citizens were organized on the basis of centuries (for military purposes) and tribes (for civil purposes). Each of the two blocks (centuries and tribes) gathered into an assembly for legislative, electoral, and judicial purposes. The Century Assembly ("Comitia Centuriata " or "Army Assembly") was the assembly of the centuries.

The 193 centuries (later 373 centuries)[54] in the Century Assembly were divided into three different grades. These were the equites, pedites and unarmed adjuncts.[55][54] The equites (cavalry) were the higher ranking soldiers who fought on horseback. They represented the elite of the army, and thus the officer class.[55] The equites were organized into eighteen centuries.[54]

The 170 centuries of pedites constituted the foot soldiers (infantry) of the Roman army. The pedites were divided into five classes,[54] with each of the five classes divided evenly between centuries of iuniores (younger soldiers) and seniores (older soldiers).[54]

The unarmed soldiers were divided into the final five centuries. Four of these centuries were composed of artisans and musicians (such as trumpeters and horn blowers). The fifth century, the proletarii, consisted of soldiers with little or no property.[56] [57]

The Century Assembly had originally been organized in a highly aristocratic manner. Later Romans believed that the legendary king Servius Tullius had been the individual who instituted this original design (the "Servian Organization").[54] Under the Servian Organization, the assembly was so aristocratic that the officer class (cavalry) and the first class of infantry controlled enough centuries for an outright majority. In 241 BC, the assembly was reorganized, and made much more democratic.[58] Under the old system, there were a total of 193 centuries. Under the new system, there were a total of 373 centuries. Now, majorities usually could not be reached until the third class of infantry had begun voting.

The seven classes (one class of cavalry, five classes of infantry, and one class of unarmed soldiers) would vote by order of seniority. The centuries in each class would vote, one at a time, until the entire class had voted. According to Cicero, the assembly was deliberately arranged in this way so that the masses would not have much power.[59] According to Livy, the purpose was so that everyone would have a vote, but the "best men" of the state would hold the most power.[60]

The president of the Century Assembly was usually a consul.[39] Only the Century Assembly could elect consuls, praetors and censors. In addition, only it could declare offensive war.[61] The Century Assembly could also pass a law that would grant imperium powers (constitutional authorization to command an army) to consuls and praetors and censorial powers to censors.[61] Only this assembly could ratify the results of a census.[51] It also served as the highest court of appeal in certain judicial cases (in particular, cases involving capital punishment).[62] While it had the power to pass ordinary laws, it rarely did so.

Assembly of the Tribes

During the years of the Roman Republic, the tribes would gather into two different assemblies. These two assemblies were the Plebeian Council (the "Concilium Plebis") and the Tribal Assembly (the "Comitia Tributa"). The only difference between the two assemblies was that patricians could not vote in the Plebeian Council. Since patricians were excluded, the Plebeian Council did not constitute the entire populus Romanus ("Roman People"). Because of this, the Plebeian Council could not elect magistrates. Instead, the Plebeian Council elected their own officers (plebeian tribunes and plebeian aediles).[63] In effect, the Plebeian Council was an "Assembly of the Plebeian Tribes", while the Tribal Assembly was an "Assembly of the Patricio-Plebeian Tribes".[64]

The president of the Tribal Assembly was usually a consul.[39] Several additional magistrates would be present during meetings, to serve as adjuncts. Their primary purpose was to help resolve procedural disputes.[65] The Tribal Assembly elected quaestors, curule aediles, and military tribunes.[66] It also had the power to try judicial cases. While the Tribal Assembly had the power to enact new laws, it rarely exercised this power.

The two tribal assemblies were composed of thirty-five blocks known as "tribes". The tribes were not ethnic or kinship groups, but rather geographical divisions.[67] This was what distinguished the tribes from the curiae. And unlike the centuries, membership in a tribe did not depend on property ownership.

Council of the Plebeians

Before the first plebeian secession (in 494 BC), the plebeians probably did gather into an assembly on the basis of the curiae. However, this assembly probably had no political role until the offices of plebeian tribune and plebeian aedile were created and formally sanctioned shortly after that secession. The plebeian tribune began presiding over the Plebeian Council ("Concilium Plebis") shortly after 494 BC. This assembly would elect both plebeian tribunes and plebeian aediles.[63] It would also pass legislation (plebiscites) which, during the early republic, would only apply to the plebeians.

Around the year 471 BC,[63] the Plebeian Council was reorganized. It began to use the tribes, rather than the curiae, as its basis for organization. When they were organized by curiae (and thus by clan), the plebeians were dependent on their patrician patrons. When they transitioned to a tribal organization (an organization based on geography rather than clan), the plebeians were no longer dependent on those patricians.[68]

Following the passage of a series of laws, the cornerstone of which was the Lex Hortensia in 287 BC, laws passed by the Plebeian Council ("plebiscites") had the full force of law. Before this point, the plebiscites only applied to the class that enacted them (the plebeians).[69] After this point, however, plebiscites applied to all of the People of Rome. From this point on, most legislation that was passed came from the Plebeian Council. Since the Plebeian Council was composed only of plebeians, it was more populist than the Tribal Assembly. Therefore, it was usually the engine behind the more controversial reforms (such as those of the tribunes Tiberius and Gaius Gracchus).

Executive Magistrates

Each Roman magistrate (magistratus) was vested with a degree of power (maior potestas or "major powers").[70] Magistrates who were vested with more "major powers" outranked magistrates who were vested with less "major powers". Dictators had more "major powers" than any other magistrate. After the dictator was the censor, and then successively the consul, the praetor, the curule aedile, and the quaestor. Each magistrate could only veto an action that was taken by a magistrate with an equal or lower degree of "major powers". Thus, no magistrate could veto an act of the senate or assemblies (since neither institution possessed any "major powers").

Since plebeian tribunes and plebeian aediles were technically not magistrates,[63] they were outside of the "major powers" standard. In general, this made them independent of the other magistrates.[39][70] This was the reason they, for example, could not have their actions vetoed by consuls. The tribune did not rely on "major powers" to obstruct (veto) magistrates, assemblies, or the senate. Tribunes relied on the sacrosanctity of their person to obstruct. If a magistrate, an assembly or the senate did not comply with the orders of a tribune, the tribune could 'interpose the sacrosanctity of his person' [37] (intercessio) to physically stop that particular action. Any resistance against the tribune would be tantamount to a violation of his sacrosanctity, and thus would be considered a capital offense.

Powers of the magistrates

Each republican magistrate held certain constitutional powers (potestas), which included "command" (imperium), "coercion" (coercitio), and religious power (auspicia). These powers were counter-balanced by several constitutional restraints, including "collegiality" (collega), the citizens' right of due process (provocatio), and a constitutional division of powers (provincia). Only the People of Rome (both plebeians and patricians) had the right to confer these powers on any individual magistrate.[71]

The most significant constitutional power was "command" (imperium). Imperium was held by both consuls and praetors. Defined narrowly, it simply gave a magistrate the authority to command a military force. Defined more broadly, however, it gave a magistrate the constitutional authority to issue commands (military, diplomatic, civil, or otherwise). A magistrate's imperium was at its apex while the magistrate was abroad. While the magistrate was in the city of Rome itself, however, he would have to completely surrender his imperium.[72]

All magistrates had the power of "coercion" (coercitio), which was used by magistrates to maintain public order.[73] While in Rome, all citizens had an absolute protection against coercion. This protection guaranteed due process rights (provocatio) to every citizen (see below).

Magistrates also had both the power and the duty to look for omens (auspicia). An omen was an event which was believed to be a sign from the gods. The "auspices" could be used to obstruct political opponents. By claiming to witness an omen, a magistrate could justify the decision to end a legislative or senate meeting, or the decision to veto a colleague.

Limitations on magisterial power

Roman magistrates had several checks on their power. One check over a magistrate's power was "collegiality" (collega). Each magisterial office would be held concurrently by at least two people, in order to minimize the risk of tyranny (and to make orderly successions easier). For example, two consuls always served together.[74]

Another check over the power of a magistrate was provocatio. Provocatio was a primordial form of due process. It was a precursor to the modern principle of habeas corpus. Any citizen in Rome had the absolute right of provocatio. If any magistrate was attempting to use the powers of the state against a citizen (such as to punish that citizen for an alleged crime), that citizen could cry "provoco ad populum". If this were to occur, a tribune would have to intervene. The tribune would have the power to unilaterally rescue that citizen.[75] Often the tribune would bring the case before a legislative assembly, a court, or the college of tribunes, for an ultimate verdict. Provocatio was the check on the magistrate's power of "coercion".

An additional check over a magistrate's power was that of provincia. Provinicia required a division of responsibilities. For example, individual governors of the provinces would each have supreme command over their province. Under the principle of provincia, these governors could not take their armies into another province.[76]

Once a magistrate's annual term in office expired, he would have to wait ten years before serving in that office again. Since this did create problems for some magistrates (in particular consuls and praetors), these magistrates would occasionally have their command powers (imperium) "prorogued". In effect, they would retain the powers of the office (as a promagistrate), without officially holding that office. In practice, they would usually act as provincial governors.[77] The frequent usage of this constitutional device, which was not in harmony with the genius of the Roman constitution, would play a significant role in the ultimate destruction of the republic.

Consuls, Praetors, Censors, Aediles, and Quaestors

The consul of the Roman Republic was the highest ranking ordinary magistrate.[39][72] Two consuls were always elected by the Century Assembly for an annual term.[78][72] Each consul would be accompanied by twelve bodyguards called lictors. Each lictor would carry a ceremonial axe known as the fasces, which would symbolize the power of the state to punish and to execute. They would also sit in a curule chair, which was a symbol of high power. Throughout the year, one consul would be superior in rank to the other consul. This ranking would flip every month, between the two consuls.[79] The consul who was superior in a given month would hold the fasces.[80]

Consuls had supreme power in both civil and military matters. While in the city of Rome, the consul who held the fasces was the head of the Roman government.[39] The management of the government would be under the ultimate authority of that consul. He would have to enforce laws passed by the assemblies[81] and policies enacted by the senate.[81] He would also preside over the assemblies and the senate.[39][81] He would act as the chief diplomat, and facilitate interactions between foreign ambassadors and the senate.[39] The consul was vested with the highest level of ordinary imperium. While abroad, each consul would command an army.[39][81] While abroad, neither the senate, the assemblies, nor a tribune could obstruct a consul. Therefore, his authority abroad would be nearly absolute.[39]

Praetors would administer civil law[82] and command provincial armies. They were elected by the Century Assembly, alongside the consuls, for a term of one year. When both consuls were away from Rome, the urban praetor would govern the city[82] as an "interim-consul". Some praetors helped to manage the central government. They would administer civil law or act as chief judges over the courts. Other praetors had foreign affairs-related responsibilities. Often these praetors would act as governors of the provinces.[83]

Every five years, two censors would be elected by the Century Assembly for an eighteen month term. Censors did not have imperium powers, and thus could convene neither the senate nor the legislative assemblies. While they did have curule chairs, they did not hold any fasces, and they were not accompanied by lictors. Since they theoretically outranked the consuls (and thus all other ordinary magistrates), their actions could only be vetoed by a fellow censor (or by a tribune).

During their term in office, the two censors would conduct a census. During the census, they could enroll citizens in the senate, or purge them from the senate.[84] During the census, the censor would have to update the list of citizens and property in the city. This would require the censor to learn various details about every citizen's life. These investigations sometimes led the censor to take actions ("censorship") against citizens to punish them for various moral failings. Such failings may have included bankruptcy or cowardice. As punishment ("censure"), the censor could fine a citizen[85] or sell his property.[84] Once the census was complete, a religious ceremony known as the lustrum would be performed by the censor. The lustrum acted as the certification of the census.[86]

Aediles were officers elected to conduct domestic affairs in Rome. The Tribal Assembly, under the presidency of a consul, would elect the two curule aediles for each annual term.[87] While the curule aediles did not hold the fasces, they did sit in a curule chair. Aediles had wide ranging powers over day-to-day affairs inside the city of Rome. They had the power over markets, and over public games and shows.[69] They also had the power to repair and preserve temples, sewers and aqueducts.[88] The office of quaestor was considered to be the lowest ranking of all major political offices.[69] The quaestors were elected by the Tribal Assembly for an annual term.[69] They would usually assist the consuls in Rome, and the governors in the provinces. Their duties were often financial.

Plebeian tribunes and plebeian aediles

Since the plebeian tribunes and plebeian aediles were elected by the plebeians, rather than by all of the People of Rome, they were technically not "magistrates". The plebeian tribunes and the plebeian aediles were both elected by the Plebeian Council. Originally, the only task of a plebeian aedile was to assist a plebeian tribune. Over time, however, the distinction between plebeian aediles and curule aediles was lost.

Since the tribunes were considered to be the embodiment of the plebeians, they were sacrosanct.[89] Their sacrosanctity was enforced by a pledge, taken by the plebeians, to kill any person who harmed or interfered with a tribune during his term of office. All of the powers of the tribune derived from their sacrosanctity. One obvious consequence of this sacrosanctity was the fact that it was considered a capital offense to harm a tribune, to disregard his veto, or to interfere with a tribune.[89] Since they were independent of all other magistrates,[81] they could only have their actions vetoed by fellow tribunes. The sacrosanctity of a tribune (and thus all of his tribunician powers), however, were only in effect so long as that tribune was in the city of Rome. If the tribune was abroad, the plebeians in Rome could not enforce their oath to kill any individual who harmed or interfered with the tribune.

Tribunes could use their sacrosanctity to order the use of capital punishment against any person who interfered with their duties.[89] Tribunes could also use their sacrosanctity as protection when physically manhandling an individual, such as when arresting someone.[90] In addition, tribunes could physically interpose themselves [37] (intercessio) against a magistrate, the senate, or an assembly. This took the form of a veto.[91] If a magistrate, the senate, or an assembly refused to abide by a tribune's veto, that tribune could use his sacrosanctity as protection, and physically force compliance.

Dictators and the "ultimate decree of the senate"

In times of military emergency, a dictator would be appointed for a term of six months.[92] Constitutional government would dissolve, and the dictator would become the absolute master of the state.[78] For a dictator to be appointed, the senate would have to pass a senatus consultum, authorizing the consuls to nominate a dictator. Once this occurred, and a dictator was nominated, that dictator took office immediately. The dictator would then appoint a master of the horse to serve as his most senior lieutenant.[80] Often the dictator would resign his office as soon as the matter that caused his appointment was resolved.[92] When the dictator's term ended, constitutional government was restored.

The last ordinary dictator was appointed in 202 BC. After 202 BC, extreme emergencies were addressed through the passage of the senatus consultum ultimum ("ultimate decree of the senate"). This suspended civil government, and declared (something analogous to) martial law.[93] In effect, it would vest the consuls with dictatorial powers.

There were several reasons why the senate began using the senatus consultum ultimum, rather than dictatorial appointments, when addressing emergencies after 202 BC. During the third century BC, a series of laws were passed which placed additional checks on the power of the dictator.[93] Also, in 217 BC, a law was passed that gave the popular assemblies the right to nominate dictators. This, in effect, eliminated the monopoly that the aristocracy had over this power.[93]

The transition from Republic to Empire

The era that began when Julius Caesar crossed the Rubicon in 49 BC, and ended when Octavian returned to Rome after Actium in 29 BC, saw the constitutional evolution of the prior century accelerate at a rapid pace. By 29 BC, Rome had completed its transition from a city-state with a network of dependencies, to the capital of a world empire.[94]

After defeating Pompey and his supporters, Caesar wanted to ensure that his control over the government was undisputed.[95] The powers which he gave himself would ultimately be used by his imperial successors.[95] He assumed these powers by increasing his own authority, and by decreasing the authority of Rome's other political institutions.

Caesar held both the dictatorship and the tribunate, but alternated between the consulship and the proconsulship.[95] In 48 BC, Caesar was given permanent tribunician powers,[96] which made his person sacrosanct, gave him the power to veto the senate, and allowed him to dominate the Plebeian Council. Since he dominated the Plebeian Council, he could pass any law he wished without opposition. In 46 BC, Caesar was given censorial powers,[96] which he used to fill the senate with his own partisans. Caesar then raised the membership of the senate to 900,[97] which robbed the senatorial aristocracy of its prestige, and made it increasingly subservient to him.[98] While the assemblies continued to meet, he submitted all candidates to the assemblies for election, and all bills to the assemblies for enactment. Thus, the assemblies became powerless, and were thus unable to oppose him.[98]

Near the end of his life, Caesar began to prepare for a war against the Parthian Empire. Since his absence from Rome would limit his ability to install his own consuls, he passed a law which allowed him to appoint all magistrates in 43 BC, and all consuls and tribunes in 42 BC.[97] This, in effect, transformed the magistrates from being representatives of the people, to being representatives of the dictator.[97]

After Caesar was assassinated in 44 BC, Mark Antony formed an alliance with Caesar's adopted son and great-nephew, Gaius Octavian. Along with Marcus Lepidus, they formed an alliance known as the Second Triumvirate,[99] and held powers that were nearly identical to the powers that Caesar had held under his constitution. As such, the senate and assemblies remained powerless, even after Caesar had been assassinated. In effect, there was no constitutional difference between an individual who held the title of dictator and an individual who held the title of triumvir. While the conspirators who had assassinated Caesar were then defeated at the Battle of Philippi in 42 BC, the peace that resulted was only temperoary, and Antony and Octavian fought against each other in one last battle. Antony was defeated in the naval Battle of Actium in 31 BC, and in 30 BC he committed suicide. In 29 BC, Octavian returned to Rome as the unchallenged master of the state, were he eventually enacted a series of constitutional reforms which overthrew the old republic. The reign of Octavian, whom history remembers as Augustus, the first Roman Emperor, marked the dividing line between the Roman Republic and the Roman Empire.

See also

Column-generating template families

The templates listed here are not interchangeable. For example, using {{col-float}} with {{col-end}} instead of {{col-float-end}} would leave a <div>...</div> open, potentially harming any subsequent formatting.

| Type | Family | Handles wiki

table code?† |

Responsive/ mobile suited |

Start template | Column divider | End template |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Float | "col-float" | Yes | Yes | {{col-float}} | {{col-float-break}} | {{col-float-end}} |

| "columns-start" | Yes | Yes | {{columns-start}} | {{column}} | {{columns-end}} | |

| Columns | "div col" | Yes | Yes | {{div col}} | – | {{div col end}} |

| "columns-list" | No | Yes | {{columns-list}} (wraps div col) | – | – | |

| Flexbox | "flex columns" | No | Yes | {{flex columns}} | – | – |

| Table | "col" | Yes | No | {{col-begin}}, {{col-begin-fixed}} or {{col-begin-small}} |

{{col-break}} or {{col-2}} .. {{col-5}} |

{{col-end}} |

† Can template handle the basic wiki markup {| | || |- |} used to create tables? If not, special templates that produce these elements (such as {{(!}}, {{!}}, {{!!}}, {{!-}}, {{!)}})—or HTML tags (<table>...</table>, <tr>...</tr>, etc.)—need to be used instead.

References

- Abbott, Frank Frost (1901). A History and Description of Roman Political Institutions. Elibron Classics. ISBN 0-543-92749-0.

- Byrd, Robert (1995). The Senate of the Roman Republic. U.S. Government Printing Office Senate Document 103-23.

- Cicero, Marcus Tullius (1841). The Political Works of Marcus Tullius Cicero: Comprising his Treatise on the Commonwealth; and his Treatise on the Laws. Vol. vol. 1 (Translated from the original, with Dissertations and Notes in Two Volumes By Francis Barham, Esq ed.). London: Edmund Spettigue.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - Lintott, Andrew (1999). The Constitution of the Roman Republic. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-926108-3.

- Polybius (1823). The General History of Polybius: Translated from the Greek. Vol. Vol 2 (Fifth Edition ed.). Oxford: Printed by W. Baxter.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help);|volume=has extra text (help) - Taylor, Lily Ross (1966). Roman Voting Assemblies: From the Hannibalic War to the Dictatorship of Caesar. The University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-08125-X.

Notes

- ^ Byrd, 161

- ^ a b Abbott, 25

- ^ Abbott, 28

- ^ a b Abbott, 37

- ^ Abbott, 42

- ^ a b Abbott, 44

- ^ Abbott, 45

- ^ Abbott, 43

- ^ a b Abbott, 46

- ^ a b c Abbott, 47

- ^ Abbott, 48

- ^ Abbott, 52

- ^ a b Abbott, 51

- ^ Abbott, 53

- ^ Abbott, 63

- ^ Abbott, 65

- ^ Abbott, 66

- ^ a b Abbott, 77

- ^ Abbott, 80

- ^ a b Abbott, 96

- ^ Abbott, 97

- ^ a b c Abbott, 98

- ^ a b c Abbott, 103

- ^ a b c d Abbott, 104

- ^ a b c d Abbott, 105

- ^ Abbott, 107

- ^ Abbott, 108

- ^ a b Abbott, 109

- ^ a b c d Abbott, 112

- ^ Abbott, 113

- ^ Abbott, 114

- ^ Abbott, 115

- ^ a b Byrd, 96

- ^ Cicero, 239

- ^ a b c Polybius, 133

- ^ a b c Byrd, 44

- ^ a b c Polybius, 136

- ^ Lintott, 72

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Polybius, 132

- ^ a b Lintott, 78

- ^ a b c Byrd, 34

- ^ Lintott, 83

- ^ a b Lintott, 42

- ^ a b Abbott, 251

- ^ Lintott, 43

- ^ Abbott, 252

- ^ a b Taylor, 2

- ^ Taylor, 40

- ^ Cicero, 211

- ^ a b c d Byrd, 33

- ^ a b c d Taylor, 3, 4

- ^ a b Abbott, 250

- ^ a b Abbott, 253

- ^ a b c d e f Cicero, 226

- ^ a b Taylor, 85

- ^ Cicero, 227

- ^ Abbott, 21

- ^ Abbott, 75

- ^ Cicero, 226-227

- ^ Taylor, 87

- ^ a b Abbott, 257

- ^ Cicero, 241

- ^ a b c d Abbott, 196

- ^ Abbott, 259

- ^ Taylor, 63

- ^ Taylor, 7

- ^ Lintott, 51

- ^ Abbott, 260

- ^ a b c d Byrd, 31

- ^ a b Abbott, 151

- ^ Lintott, 95

- ^ a b c Byrd, 20

- ^ Lintott, 97

- ^ Lintott, 101

- ^ Cicero, 235

- ^ Lintott, 101-102

- ^ Lintott, 113

- ^ a b Cicero, 237

- ^ Cicero, 236

- ^ a b Byrd, 42

- ^ a b c d e Byrd, 179

- ^ a b Byrd, 32

- ^ Lintott, 107-109

- ^ a b Byrd, 26

- ^ Cicero, 240

- ^ Lintott, 119

- ^ Lintott, 130

- ^ Lintott, 129, 130-131

- ^ a b c Byrd, 23

- ^ Lintott, 123

- ^ Lintott, 122

- ^ a b Byrd, 24

- ^ a b c Abbott, 240

- ^ Abbott, 129

- ^ a b c Abbott, 134

- ^ a b Abbott, 135

- ^ a b c Abbott, 137

- ^ a b Abbott, 138

- ^ Goldsworthy, In the Name of Rome, p. 237

Further reading

- Ihne, Wilhelm (1853). Researches Into the History of the Roman Constitution. William Pickering.

- Johnston, Harold Whetstone (1891). Orations and Letters of Cicero: With Historical Introduction, An Outline of the Roman Constitution, Notes, Vocabulary and Index. Scott, Foresman and Company.

- Mommsen, Theodor (1888). Roman Constitutional Law.

- Polybius. The Histories; Volumes 9–13. Cambridge Ancient History.

- Tighe, Ambrose (1886). The Development of the Roman Constitution. D. Apple & Co.

- Von Fritz, Kurt (1975). The Theory of the Mixed Constitution in Antiquity. Columbia University Press, New York.

Primary sources

- Cicero's De Re Publica, Book Two

- Rome at the End of the Punic Wars: An Analysis of the Roman Government; by Polybius

Secondary source material

- Considerations on the Causes of the Greatness of the Romans and their Decline, by Montesquieu

- The Roman Constitution to the Time of Cicero

- What a Terrorist Incident in Ancient Rome Can Teach Us