Dark Romanticism

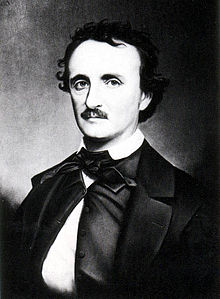

Dark romanticism (often conflated with Gothicism or called American romanticism) is a literary subgenre[1] centered on the writers Edgar Allan Poe, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Herman Melville.[2]

As opposed to the perfectionist beliefs of Transcendentalism, the Dark Romantics emphasized human fallibility and proneness to sin and self-destruction, as well as the difficulties inherent in attempts at social reform.[3]

Characteristics

G. R. Thompson stressed that in opposition to the optimism of figures like Emerson, “the Dark Romantics adapted images of anthropomorphized evil in the form of Satan, devils, ghosts, werewolves, vampires, and ghouls”,[4] as more telling guides to man's inherent nature.

Thompson sums up the characteristics of the subgenre, writing:

Fallen man's inability fully to comprehend haunting reminders of another, supernatural realm that yet seemed not to exist, the constant perplexity of inexplicable and vastly metaphysical phenomena, a propensity for seemingly perverse or evil moral choices that had no firm or fixed measure or rule, and a sense of nameless guilt combined with a suspicion the external world was a delusive projection of the mind--these were major elements in the vision of man the Dark Romantics opposed to the mainstream of Romantic thought.[5]

Wider movements

While primarily associated with New England writers, elements of dark romanticism were a perennial possibility within the broader international movement Romanticism, in both literature and art.[6]

British authors such as Lord Byron, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Mary Shelley, and John William Polidori, who are frequently linked to Gothic fiction, are also sometimes referred to as Dark Romantics.[7] Their tales and poems commonly feature outcasts from society, personal torment and uncertainty as to whether the nature of man will bring him salvation or destruction.[citation needed]

Dark romanticism was also particularly important in Germany, with writers such as E. T. A. Hoffmann,[8] Christian Heinrich Spiess, and Ludwig Tieck – though their emphasis on existential alienation, the demonic in sex, and the uncanny,[9] was offset at the same time by the more homely cult of Biedermeier.[10]

Later influence

Dark romanticism of the New England school found a more naturalistic development toward the end of the century in the works of Edith Wharton and Henry James, where ghosts became emblems of psychological events.[2]

Twentieth-century existential novels have also been linked to dark romanticism,[11] as too have the sword and sorcery novels of Robert E. Howard.[12]

Criticism

Northrop Frye pointed to the dangers of the demonic myth making of the dark side of romanticism as seeming “to provide all the disadvantages of superstition with none of the advantages of religion”.[13]

See also

References

- ^ Dark Romanticism: The Ultimate Contradiction

- ^ a b Robin Peel, Apart from Modernism (2005) p. 136

- ^ T. Nitscke, Edgar Alan Poe's short story “The Tell-Tale Heart” (2012) p. 5–7

- ^ Thompson, G. R., ed. "Introduction: Romanticism and the Gothic Tradition." Gothic Imagination: Essays in Dark Romanticism. Pullman, WA: Washington State University Press, 1974: p. 6.

- ^ Thompson, G.R., ed. 1974: p. 5.

- ^ Felix Kramer, Dark Romanticism: From Goya to Max Ernst (2012)

- ^ University of Delaware: Dark Romanticism

- ^ A. Cusak/B. Murnane, Popular Revenants (2012) p. 19

- ^ S. Freud, 'The Uncanny' Imago (1919) p. 19-60

- ^ S. Prickett/S. Haines, European Romanticism (2010) p. 32

- ^ R. Kopley, Poe's Pym (1992) p. 141

- ^ D. Herron, The Dark Barbarian (1984) p. 57

- ^ Northrop Frye, Anatomy of Criticism (1973) p. 157

Further reading

- Galens, David, ed. (2002) Literary Movements for Students Vol. 1.

- Harry Levin, The Power of Blackness (1958)

- Mario Praz The Romantic Agony (1933)

- Mullane, Janet and Robert T. Wilson, eds. (1989) Nineteenth Century Literature Criticism Vols. 1, 16, 24.