Demon

A demon (from Koine Greek δαιμόνιον daimonion) is a supernatural, often malevolent being prevalent in religion, occultism, literature, fiction, mythology and folklore.

The original Greek word daimon does not carry the negative connotation initially understood by implementation of the Koine δαιμόνιον (daimonion),[1] and later ascribed to any cognate words sharing the root.

In Ancient Near Eastern religions as well as in the Abrahamic traditions, including ancient and medieval Christian demonology, a demon is considered an unclean spirit, a fallen angel, or a spirit of unknown type which may cause demonic possession, calling for an exorcism. In Western occultism and Renaissance magic, which grew out of an amalgamation of Greco-Roman magic, Jewish Aggadah and Christian demonology,[2] a demon is believed to be a spiritual entity that may be conjured and controlled.

Etymology

The Ancient Greek word δαίμων daimōn denotes a spirit or divine power, much like the Latin genius or numen. Daimōn most likely came from the Greek verb daiesthai (to divide, distribute).[3] The Greek conception of a daimōn notably appears in the works of Plato, where it describes the divine inspiration of Socrates. To distinguish the classical Greek concept from its later Christian interpretation, the former is anglicized as either daemon or daimon rather than demon.[citation needed]

The Greek terms do not have any connotations of evil or malevolence. In fact, εὐδαιμονία eudaimonia, (literally good-spiritedness) means happiness. By the early Roman Empire, cult statues were seen, by pagans and their Christian neighbors alike, as inhabited by the numinous presence of the gods: "Like pagans, Christians still sensed and saw the gods and their power, and as something, they had to assume, lay behind it, by an easy traditional shift of opinion they turned these pagan daimones into malevolent 'demons', the troupe of Satan..... Far into the Byzantine period Christians eyed their cities' old pagan statuary as a seat of the demons' presence. It was no longer beautiful, it was infested."[4] The term had first acquired its negative connotations in the Septuagint translation of the Hebrew Bible into Greek, which drew on the mythology of ancient Semitic religions. This was then inherited by the Koine text of the New Testament. The Western medieval and neo-medieval conception of a demon[5] derives seamlessly from the ambient popular culture of Late Antiquity. The Hellenistic "daemon" eventually came to include many Semitic and Near Eastern gods as evaluated by Christianity.[citation needed]

The supposed existence of demons remains an important concept in many modern religions and occultist traditions. Demons are still feared largely due to their alleged power to possess living creatures. In the contemporary Western occultist tradition (perhaps epitomized by the work of Aleister Crowley), a demon (such as Choronzon, the Demon of the Abyss) is a useful metaphor for certain inner psychological processes (inner demons), though some may also regard it as an objectively real phenomenon. Some scholars[6] believe that large portions of the demonology (see Asmodai) of Judaism, a key influence on Christianity and Islam, originated from a later form of Zoroastrianism, and were transferred to Judaism during the Persian era.

Ancient Near East

Mesopotamia

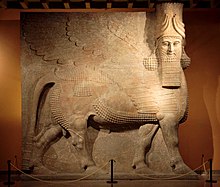

According to the Jewish Encyclopedia, "In Chaldean mythology the seven evil deities were known as shedu, storm-demons, represented in ox-like form."[7] They were represented as winged bulls, derived from the colossal bulls used as protective jinn of royal palaces.[8]

From Chaldea, the term shedu traveled to the Israelites. The writers of the Tanach applied the word as a dialogism to Canaanite deities.

There are indications that demons in popular Hebrew mythology were believed to come from the nether world.[9] Various diseases and ailments were ascribed to them, particularly those affecting the brain and those of internal nature. Examples include catalepsy, headache, epilepsy and nightmares. There also existed a demon of blindness, "Shabriri" (lit. "dazzling glare") who rested on uncovered water at night and blinded those who drank from it.[10]

Demons supposedly entered the body and caused the disease while overwhelming or "seizing" the victim. To cure such diseases, it was necessary to draw out the evil demons by certain incantations and talismanic performances, at which the Essenes excelled. Josephus, who spoke of demons as "spirits of the wicked which enter into men that are alive and kill them", but which could be driven out by a certain root,[11] witnessed such a performance in the presence of the Emperor Vespasian[12] and ascribed its origin to King Solomon. In mythology, there were few defences against Babylonian demons. The mythical mace Sharur had the power to slay demons such as Asag, a legendary gallu or edimmu of hideous strength.

Judaism

As referring to the existence or non-existence of shedim (Hebr. for "demons", "spirits") there are converse opinions in Judaism.[13] There are "practically nil" roles assigned to demons in the Jewish Bible.[14] In Judaism today, beliefs in shedim ("demons" or "evil spirits") are either midot hasidut (Hebr. for "customs of the pious"), and therefore not halachah, or notions based on a superstition that are non-essential, non-binding parts of Judaism, and therefore not normative Jewish practice. In conclusion, Jews are not obligated to believe in the existence of shedim, as posek rabbi David Bar-Hayim points out.[15][16][17]

Tanach

The word shedim (Hebr. for "demons" or "spirits") appears only in two places in the Tanakh (Psalm 106:37, Deuteronomy 32:17). In both places, the term appears in a scriptural context of animal or child sacrifice to non-existent false gods that are called shedim.[13][14][18]

Talmudic tradition

In the Jerusalem Talmud notions of shedim ("demons" or "evil spirits") are almost unknown or occur only very rarely, whereas in the Babylon Talmud there are many references to shedim and magical incantations. The existence of shedim in general was not questioned by most of the Babylonian Talmudists. As a consequence of the rise of influence of the Babylonian Talmud over that of the Jerusalem Talmud, late rabbis in general took as fact the existence of shedim, nor did most of the medieval thinkers question their reality. However, rationalists like Maimonides, Saadia Gaon and Abraham ibn Ezra and others explicitly denied their existence, and completely rejected concepts of demons, evil spirits, negative spiritual influences, attaching and possessing spirits. Their point of view eventually became mainstream Jewish understanding.[13][15]

Kabbalah

Some benevolent shedim were used in kabbalistic ceremonies (as with the golem of Rabbi Yehuda Loevy) and malevolent shedim (mazikin, from the root meaning "to damage") were often credited with possession.[citation needed]

Aggadah

Aggadic tales from the Persian tradition describe the shedim, the mazziḳim ("harmers"), and the ruḥin ("spirits"). There were also lilin ("night spirits"), ṭelane ("shade", or "evening spirits"), ṭiharire ("midday spirits"), and ẓafrire ("morning spirits"), as well as the "demons that bring famine" and "such as cause storm and earthquake".[19][20] According to some aggadic stories about demons is told that they were under the dominion of a king or chief, either Asmodai[21] or, in the older Aggadah, Samael ("the angel of death"), who killed via poison. Stories in the fashion of this kind of folklore never became an essential feature of Jewish theology.[15] Although occasionally an angel is called satan in the Babylon Talmud, this does not refer to a demon: "Stand not in the way of an ox when coming from the pasture, for Satan dances between his horns".[22]

Second Temple period texts

To the Qumran community during the Second Temple period this apotropaic prayer was assigned, stating: "And, I the Sage, declare the grandeur of his radiance in order to frighten and terri[fy] all the spirits of the ravaging angels and the bastard spirits, demons, Liliths, owls" (Dead Sea Scrolls, "Songs of the Sage," Lines 4–5).[23][24]

In the Dead Sea Scrolls, there exists a fragment entitled “Curses of Belial” (Curses of Belial (Dead Sea Scrolls, 394, 4Q286(4Q287, fr. 6)=4QBerakhot)). This fragment holds much rich language that reflects the sentiment shared between the Qumran towards Belial. In many ways this text shows how these people thought Belial influenced sin through the way they address him and speak of him. By addressing “Belial and all his guilty lot,” (4Q286:2) they make it clear that he is not only impious, but also guilty of sins. Informing this state of uncleanliness are both his “hostile” and “wicked design” (4Q286:3,4). Through this design, Belial poisons the thoughts of those who are not necessarily sinners. Thus a dualism is born from those inclined to be wicked and those who aren’t.[25] It is clear that Belial directly influences sin by the mention of “abominable plots” and “guilty inclination” (4Q286:8,9). These are both mechanisms by which Belial advances his evil agenda that the Qumran have exposed and are calling upon God to protect them from. There is a deep sense of fear that Belial will “establish in their heart their evil devices” (4Q286:11,12). This sense of fear is the stimulus for this prayer in the first place. Without the worry and potential of falling victim to Belial’s demonic sway, the Qumran people would never feel impelled to craft a curse. This very fact illuminates the power Belial was believed to hold over mortals, and the fact that sin proved to be a temptation that must stem from an impure origin.

In Jubilees 1:20, Belial’s appearance continues to support the notion that sin is a direct product of his influence. Moreover, Belial’s presence acts as a placeholder for all negative influences or those that would potentially interfere with God’s will and a pious existence. Similarly to the “gentiles…[who] cause them to sin against you” (Jubilees 1:19), Belial is associated with a force that drives one away from God. Coupled in this plea for protection against foreign rule, in this case the Egyptians, is a plea for protection from “the spirit of Belial” (Jubilees 1:19). Belial’s tendency is to “ensnare [you] from every path of righteousness” (Jubilees 1:19). This phrase is intentionally vague, allowing room for interpretation. Everyone, in one way or another, finds themselves straying from the path of righteousness and by pawning this transgression off on Belial, he becomes a scapegoat for all misguidance, no matter what the cause. By associating Belial with all sorts of misfortune and negative external influence, the Qumran people are henceforth allowed to be let off for the sins they commit.

Belial’s presence is found throughout the War Scrolls, located in the Dead Sea Scrolls, and is established as the force occupying the opposite end of the spectrum of God. In Col. I, verse 1, the very first line of the document, it is stated that “the first attack of the Sons of Light shall be undertaken against the forces of the Sons of Darkness, the army of Belial” (1Q33;1:1).[26] This dichotomy sheds light on the negative connotations that Belial held at the time.[27] Where God and his Sons of Light are forces that protect and promote piety, Belial and his Sons of Darkness cater to the opposite, instilling the desire to sin and encouraging destruction. This opposition is only reinforced later in the document; it continues to read that the “holy ones” will “strike a blow at wickedness,” ultimately resulting in the “annihilation of the Sons of Darkness” (1Q33:1:13). This epic battle between good and evil described in such abstract terms, however it is also applicable to everyday life and serves as a lens through which the Qumran see the world. Every day is the Sons of Light battle evil and call upon God to help them overcome evil in ways small and large.

Belial’s influence is not taken lightly. In Col. XI, verse 8, the text depicts God conquering the “hordes of Belial” (1Q33;11:8). This defeat is indicative of God’s power over Belial and his forces of temptation. However the fact that Belial is the leader of hordes is a testament to how persuasive he can be. If Belial was obviously an arbiter of wrongdoing and was blatantly in the wrong, he wouldn’t be able to amass an army. This fact serves as a warning message, reasserting God’s strength, while also making it extremely clear the breadth of Belial’s prowess. Belial’s “council is to condemn and convict,” so the Qumran feel strongly that their people are not only aware of his purpose, but also equipped to combat his influence (1Q33;13:11).

In the Damascus Document, Belial also makes a prominent appearance, being established as a source of evil and an origin of several types of sin. In Column 4, the first mention of Belial reads: “Belial shall be unleashed against Israel” (4Q266). This phrase is able to be interpreted myriad different ways. Belial is characterized in a wild and uncontrollable fashion, making him seem more dangerous and unpredictable. The notion of being unleashed is such that once he is free to roam; he is unstoppable and able to carry out his agenda uninhibited. The passage then goes to enumerate the “three nets” (4Q266;4:16) by which Belial captures his prey and forces them to sin. “Fornication…, riches..., [and] the profanation of the temple” (4Q266;4:17,18) make up the three nets. These three temptations were three agents by which people were driven to sin, so subsequently, the Qumran people crafted the nets of Belial to rationalize why these specific temptations were so toxic. Later in Column 5, Belial is mentioned again as one of “the removers of bound who led Israel astray” (4Q266;5:20). This statement is a clear display of Belial’s influence over man regarding sin. The passage goes on to state: “they preached rebellion against...God” (4Q266;5:21,22). Belial’s purpose is to undermine the teachings of God, and he achieves this by imparting his nets on humans, or the incentive to sin.[28]

In the War of the Sons of Light Against the Sons of Darkness, Belial controls scores of demons, which are specifically allotted to him by God for the purpose of performing evil.[29] Belial, despite his malevolent disposition, is considered an angel.[30]

Christianity

Christian Bible

Old Testament

Demons in the Old Testament of the Christian Bible are of two classes: the "satyrs" or "shaggy goats" (from Hebr. se'irim "hairy beings" and Greek Old Testament σάτυρος satyros, "satyr"; Isaiah 13:21, 34:14)[31] and the "demons" (from Hebr. shedim, and Koine Greek δαιμόνιον daimonion; 106:35–39, 32:17).

New Testament

The term "demon" (from the Greek New Testament δαιμόνιον daimonion) appears 63 times in the New Testament of the Christian Bible.[32][33][34]

Pseudepigrapha and Deuterocanonical books

Demons are sometimes included into biblical interpretation. In the story of Passover, the Bible tells the story as "the Lord struck down all the firstborn in Egypt" (Exodus 12:21–29). In the Book of Jubilees, which is considered canonical only by the Ethiopian Orthodox Church,[35] this same event is told slightly differently: "All the powers of [the demon] Mastema had been let loose to slay all the first-born in the land of Egypt...And the powers of the Lord did everything according as the Lord commanded them" (Jubilees 49:2–4).

In the Genesis flood narrative the author explains how God was noticing "how corrupt the earth had become, for all the people on earth had corrupted their ways" (Genesis 6:12). In Jubilees the sins of man are attributed to "the unclean demons [who] began to lead astray the children of the sons of Noah, and to make to err and destroy them" (Jubilees 10:1). In Jubilees Mastema questions the loyalty of Abraham and tells God to "bid him offer him as a burnt offering on the altar, and Thou wilt see if he will do this command" (Jubilees 17:16). The discrepancy between the story in Jubilees and the story in Genesis 22 exists with the presence of Mastema. In Genesis, God tests the will of Abraham merely to determine whether he is a true follower, however; in Jubilees Mastema has an agenda behind promoting the sacrifice of Abraham’s son, "an even more demonic act than that of the Satan in Job."[36] In Jubilees, where Mastema, an angel tasked with the tempting of mortals into sin and iniquity, requests that God give him a tenth of the spirits of the children of the watchers, demons, in order to aid the process.[37] These demons are passed into Mastema’s authority, where once again, an angel is in charge of demonic spirits.

The sources of demonic influence were thought to originate from the Watchers or Nephilim, who are first mentioned in Genesis 6 and are the focus of 1 Enoch Chapters 1–16, and also in Jubilees 10. The Nephilim were seen as the source of the sin and evil on earth because they are referenced in Genesis 6:4 before the story of the Flood.[39] In Genesis 6:5, God sees evil in the hearts of men. The passage states, “the wickedness of humankind on earth was great”, and that “Every inclination of the thoughts of their hearts was only continually evil” (Genesis 5). The mention of the Nephilim in the preceding sentence connects the spread of evil to the Nephilim. Enoch is a very similar story to Genesis 6:4–5, and provides further description of the story connecting the Nephilim to the corruption of humans. In Enoch, sin originates when angels descend from heaven and fornicate with women, birthing giants as tall as 300 cubits. The giants and the angels’ departure of Heaven and mating with human women are also seen as the source of sorrow and sadness on Earth. The book of Enoch shows that these fallen angels can lead humans to sin through direct interaction or through providing forbidden knowledge. In Enoch, Semyaz leads the angels to mate with women. Angels mating with humans is against God’s commands and is a cursed action, resulting in the wrath of God coming upon Earth. Azazel indirectly influences humans to sin by teaching them divine knowledge not meant for humans. Asael brings down the “stolen mysteries” (Enoch 16:3). Asael gives the humans weapons, which they use to kill each other. Humans are also taught other sinful actions such as beautification techniques, alchemy, astrology and how to make medicine (considered forbidden knowledge at the time). Demons originate from the evil spirits of the giants that are cursed by God to wander the earth. These spirits are stated in Enoch to “corrupt, fall, be excited, and fall upon the earth, and cause sorrow” (Enoch 15:11).[40]

The Book of Jubilees conveys that sin occurs when Cainan accidentally transcribes astrological knowledge used by the Watchers (Jubilees 8). This differs from Enoch in that it does not place blame on the Angels. However, in Jubilees 10:4 the evil spirits of the Watchers are discussed as evil and still remain on earth to corrupt the humans. God binds only 90 percent of the Watchers and destroys them, leaving 10 percent to be ruled by Mastema. Because the evil in humans is great, only 10 percent would be needed to corrupt and lead humans astray. These spirits of the giants also referred to as “the bastards” in the Apotropaic prayer Songs of the Sage, which lists the names of demons the narrator hopes to expel.[41]

Christian demonology

In the Christian Bible, the deities of other religions are sometimes interpreted or created as "demons" (from the Greek Old Testament δαιμόνιον daimonion).[42] The evolution of the Christian Devil and pentagram are examples of early rituals and images that showcase evil qualities, as seen by the Christian churches.

Since Early Christianity, demonology has developed from a simple acceptance of demons to a complex study that has grown from the original ideas taken from Jewish demonology[citation needed] and Christian scriptures. Christian demonology is studied in depth within the Roman Catholic Church,[43] although many other Christian churches affirm and discuss the existence of demons.[44][45]

Building upon the few references to daemons in the New Testament, especially the poetry of the Book of Revelation, Christian writers of apocrypha from the 2nd century onwards created a more complicated tapestry of beliefs about "demons" that was largely independent of Christian scripture.

The contemporary Roman Catholic Church unequivocally teaches that angels and demons are real beings rather than just symbolic devices. The Catholic Church has a cadre of officially sanctioned exorcists which perform many exorcisms each year. The exorcists of the Catholic Church teach that demons attack humans continually but that afflicted persons can be effectively healed and protected either by the formal rite of exorcism, authorized to be performed only by bishops and those they designate, or by prayers of deliverance, which any Christian can offer for themselves or others.[46]

At various times in Christian history, attempts have been made to classify demons according to various proposed demonic hierarchies.

In the Gospels, particularly the Gospel of Mark, Jesus cast out many demons from those afflicted with various ailments. He also lent this power to some of his disciples (Luke 10:17).

Apuleius, by Augustine of Hippo, is ambiguous as to whether daemons had become 'demonized' by the early 5th century:

- He [Apulieus] also states that the blessed are called in Greek eudaimones, because they are good souls, that is to say, good demons, confirming his opinion that the souls of men are demons.[47]

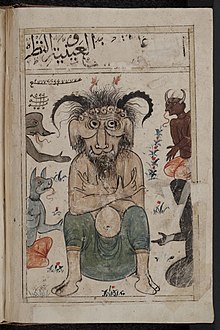

Islam

The numerous mentions of jinn in the Quran and testimony of both pre-Islamic and Islamic literature indicate that the belief in spirits was prominent in pre-Islamic Bedouin religion.[48] There is evidence that the word jinn is derived from Aramaic, where it was used by Christians to designate pagan gods reduced to the status of demons, and was introduced into Arabic folklore only late in the pre-Islamic era.[48] Julius Wellhausen has observed that such spirits were thought to inhabit desolate, dingy and dark places and that they were feared.[48]

Islam recognizes the existence of jinn, which are sentient beings with free will that can co-exist with humans (though not the genies of modern lore). In Islam, evil jinn are referred to as the shayātīn or demons/devils, with Iblis (Satan) as their chief. Iblis was either the first jinn or a fallen angel, who became the leader of the jinn;[49] he disobeyed Allah and did not bow down before Adam refusing to acknowledge a creature made of "clay". Thus, Iblis was banished from Jannah (Heaven). He asked for respite until the Last Day (Judgement Day), when he vowed to make mankind fall and deny the existence of their creator, to which Allah replied that Iblis would only be able to mislead those who were not righteous believers, warning that Iblis and all who followed him in evil would be punished in Hell.

Hinduism

Hindu beliefs include numerous varieties of spirits that might be classified as demons, including Vetalas, Bhutas and Pishachas. Rakshasas and Asuras are often also taken as demons.

Asuras

Originally, Asura, in the earliest hymns of the Rig Veda, meant any supernatural spirit, either good or bad. Since the /s/ of the Indic linguistic branch is cognate with the /h/ of the Early Iranian languages, the word Asura, representing a category of celestial beings, became the word Ahura (Mazda), the Supreme God of the monotheistic Zoroastrians. Ancient Hinduism tells that Devas (also called suras) and Asuras are half-brothers, sons of the same father Kashyapa; although some of the Devas, such as Varuna, are also called Asuras. Later, during Puranic age, Asura and Rakshasa came to exclusively mean any of a race of anthropomorphic, powerful, possibly evil beings. Daitya (lit. sons of the mother "Diti"), Rakshasa (lit. from "harm to be guarded against"), and Asura are incorrectly translated into English as "demon".

Post Vedic, Hindu scriptures, pious, highly enlightened Asuras, such as Prahlada and Vibhishana, are not uncommon. The Asura are not fundamentally against the gods, nor do they tempt humans to fall. Many people metaphorically interpret the Asura as manifestations of the ignoble passions in the human mind and as a symbolic devices. There were also cases of power-hungry Asuras challenging various aspects of the Gods, but only to be defeated eventually and seek forgiveness—see Surapadman and Narakasura.

Evil spirits

Hinduism advocates the reincarnation and transmigration of souls according to one's karma. Souls (Atman) of the dead are adjudged by the Yama and are accorded various purging punishments before being reborn. Humans that have committed extraordinary wrongs are condemned to roam as lonely, often evil, spirits for a length of time before being reborn. Many kinds of such spirits (Vetalas, Pishachas, Bhūta) are recognized in the later Hindu texts. These beings, in a limited sense, can be called demons.

Bahá'í Faith

In the Bahá'í Faith, demons are not regarded as independent evil spirits as they are in some faiths. Rather, evil spirits described in various faiths' traditions, such as Satan, fallen angels, demons and jinns, are metaphors for the base character traits a human being may acquire and manifest when he turns away from God and follows his lower nature. Belief in the existence of ghosts and earthbound spirits is rejected and considered to be the product of superstition.[50]

Ceremonial magic

While some people fear demons, or attempt to exorcise them, others willfully attempt to summon them for knowledge, assistance, or power. The ceremonial magician usually consults a grimoire, which gives the names and abilities of demons as well as detailed instructions for conjuring and controlling them. Grimoires aren't limited to demons – some give the names of angels or spirits which can be called, a process called theurgy. The use of ceremonial magic to call demons is also known as goetia, the name taken from a section in the famous grimoire the Lesser Key of Solomon.[51]

Wicca

According to Rosemary Ellen Guiley, "Demons are not courted or worshipped in contemporary Wicca and Paganism. The existence of negative energies is acknowledged."[52]

Modern interpretations

Psychologist Wilhelm Wundt remarked that "among the activities attributed by myths all over the world to demons, the harmful predominate, so that in popular belief bad demons are clearly older than good ones."[53] Sigmund Freud developed this idea and claimed that the concept of demons was derived from the important relation of the living to the dead: "The fact that demons are always regarded as the spirits of those who have died recently shows better than anything the influence of mourning on the origin of the belief in demons."[54]

M. Scott Peck, an American psychiatrist, wrote two books on the subject, People of the Lie: The Hope For Healing Human Evil[55] and Glimpses of the Devil: A Psychiatrist's Personal Accounts of Possession, Exorcism, and Redemption.[56] Peck describes in some detail several cases involving his patients. In People of the Lie he provides identifying characteristics of an evil person, whom he classified as having a character disorder. In Glimpses of the Devil Peck goes into significant detail describing how he became interested in exorcism in order to debunk the myth of possession by evil spirits – only to be convinced otherwise after encountering two cases which did not fit into any category known to psychology or psychiatry. Peck came to the conclusion that possession was a rare phenomenon related to evil, and that possessed people are not actually evil; rather, they are doing battle with the forces of evil.[57]

Although Peck's earlier work was met with widespread popular acceptance, his work on the topics of evil and possession has generated significant debate and derision. Much was made of his association with (and admiration for) the controversial Malachi Martin, a Roman Catholic priest and a former Jesuit, despite the fact that Peck consistently called Martin a liar and manipulator.[58][59] Richard Woods, a Roman Catholic priest and theologian, has claimed that Dr. Peck misdiagnosed patients based upon a lack of knowledge regarding dissociative identity disorder (formerly known as multiple personality disorder), and had apparently transgressed the boundaries of professional ethics by attempting to persuade his patients into accepting Christianity.[58] Father Woods admitted that he has never witnessed a genuine case of demonic possession in all his years.[60][61][62]

According to the Hong Kong Journal of Psychiatry, God is shown sending a demon against Saul in 1 Samuel 16 and 18 in order to punish him for the failure to follow God’s instructions, showing God as having the power to use demons for his own purposes, putting the demon under his divine authority.[63] According to the Britannica Concise Encyclopedia, demons, despite being typically associated with evil, are often shown to be under divine control, and not acting of their own devices.[64]

See also

References

- ^ Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott. "δαιμόνιον". Greek-English Lexicon. Perseus.

- ^ See, for example, the course synopsis and bibliography for "Magic, Science, Religion: The Development of the Western Esoteric Traditions"[dead link], at Central European University, Budapest

- ^ "Demon". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 12 April 2012.

- ^ Robin Lane Fox, Pagans and Christians 1989, p.137.

- ^ See the Medieval grimoire called the Ars Goetia.

- ^ Boyce, 1987; Black and Rowley, 1987; Duchesne-Guillemin, 1988.

- ^ Jewish Encyclopedia. 1906.

- ^ See Delitzsch, Assyrisches Handwörterbuch. pp. 60, 253, 261, 646; Jensen, Assyr.-Babyl. Mythen und Epen, 1900, p. 453; Archibald Sayce, l.c. pp. 441, 450, 463; Lenormant, l.c. pp. 48–51.

- ^ compare Isaiah 38:11 with Job 14:13; Psalms 16:10, 49:16, and 139:8

- ^ Isaacs, Ronald H. (1998). Ascending Jacob's Ladder: Jewish Views of Angels, Demons, and Evil Spirits. Jason Aronson. p. 96. ISBN 978-0-7657-5965-8. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

- ^ Bellum Judaeorum vii. 6, § 3

- ^ "Antiquities" viii. 2, § 5

- ^ a b c "The Jewish Encyclopedia". The Jewish Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2014-03-12.

- ^ a b "Demons & Demonology". jewishvirtuallibrary.org. The Gale Group. Retrieved 21 March 2015.

- ^ a b c Bar-Hayim, David (HaRav). "Do Jews Believe in Demons and Evil Spirits?". http://machonshilo.org. Machon Shilo. Retrieved 20 March 2015.

{{cite web}}: External link in|website= - ^ "האם יהודים מאמינים בשדים וברוחות רעות? ראיון עם הרב דוד בר חיים". www.youtube.com. Tora Nation Machon Shilo. Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- ^ Bar-Hayim, David. "Do Jews Believe in Demons and Evil Spirits?-Interview with Rabbi David Bar-Hayim". www.youtube.com. Tora Nation Machon Shilo. Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- ^ W. Gunther Plaut, The Torah: A Modern Commentary (Union for Reform Judaism, 2005), p. 1403 online

- ^ (Targ. Yer. to Deuteronomy xxxii. 24 and Numbers vi. 24; Targ. to Cant. iii. 8, iv. 6; Eccl. ii. 5; Ps. xci. 5, 6.)

- ^ "Jewish Encyclopedia Demonology". Retrieved 2007-05-03.

- ^ Targ. to Eccl. i. 13; Pes. 110a; Yer. Shek. 49b

- ^ Pes. 112b; compare B. Ḳ. 21a

- ^ García, Martínez Florentino. The Dead Sea Scrolls Translated: The Qumran Texts in English. Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1994. Print.

- ^ Florentino Martinez Garcia, Magic in the Dead Sea Scrolls: The Metamorphosis of Magic: From Late Antiquity to the Early Modern Period, compilers Jan Bremmer and Jan R. Veenstra (Leuven: Peeters, 2003).

- ^ Author=Frey, J. Title=DIFFERENT PATTERNS OF DUALISTIC THOUGHT IN THE QUMRAN LIBRARY IN: Legal Texts And Legal Issues, Year=1984, p. 287

- ^ Author=Nickelsburg, George. Title="Jewish Literature between the Bible and the Mishna." N.d. Digital file.

- ^ Author=Frey, J. Title=DIFFERENT PATTERNS OF DUALISTIC THOUGHT IN THE QUMRAN LIBRARY IN: Legal Texts And Legal Issues, Year=1984, p. 278

- ^ Author=Nickelsburg, George. Title="Jewish Literature between the Bible and the Mishna." N.d. Digital file, p. 147.

- ^ Dead Sea Scrolls 1QS III 20–25

- ^ Dale Basil Martin, “When did Angels Become Demons?” Journal of Biblical Literature (2010): 657–677.

- ^ "Hebrew Concordance: ū·śə·'î·rîm – 1 Occurrence". Biblesuite.com. Retrieved 2014-03-12.

- ^ "1140. daimonion". http://biblehub.com/greek/. Biblos.com. Retrieved 20 March 2015.

{{cite web}}: External link in|website= - ^ Dan Burton and David Grandy, Magic, Mystery, and Science: The Occult in Western Civilization (Indiana University Press, 2003), p. 120 online.

- ^ Encyclopedia of Spirits: The Ultimate Guide to the Magic of Fairies, Genies, Demons, Ghosts, Gods & Goddesses – Judika Illes – HarperCollins, Jan 2009 – p. 902 [1]

- ^ Harris, Stephen L., Understanding the Bible. Palo Alto: Mayfield. 1985. It is considered one of the pseudepigrapha by Protestant, Roman Catholic, and Eastern Orthodox Churches

- ^ Moshe Berstein, Angels at the Aqedah: A Study in the Development of a Midrashic Motif, (Dead Sea Discoveries, 7, 2000), 267.

- ^ Jubilees 10:7–9

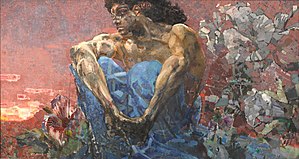

- ^ Sara Elizabeth Hecker. Dueling Demons: Mikhail Vrubel’s Demon Seated and Demon Downcast. Art in Russia, the School of Russian and Asian Studies, 2012

- ^ Hanneken Henoch,, T. R. (2006). ANGELS AND DEMONS IN THE BOOK OF JUBILEES AND CONTEMPORARY APOCALYPSES. pp. 11–25.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ VanderKam, James C. (1999). THE ANGEL STORY IN THE BOOK OF JUBILEES IN: Pseudepigraphic Perspectives : The Apocrypha And Pseudepigrapha In Light Of The Dead Sea Scrolls. pp. 151–170.

- ^ Vermes, Geza (2011). The complete Dead Sea scrolls in English. London: Penguin. p. 375.

- ^ van der Toorn, Becking, van der Horst (1999), Dictionary of Deities and Demons in The Bible, Second Extensively Revised Edition, Entry: Demon, pp. 235-240, William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, ISBN 0-8028-2491-9

- ^ Exorcism, Sancta Missa – Rituale Romanum, 1962, at sanctamissa.org, Copyright © 2007. Canons Regular of St. John Cantius

- ^ Hansen, Chadwick (1970), Witchcraft at Salem, p. 132, Signet Classics, Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 69-15825

- ^ Modica, Terry Ann (1996), Overcoming The Power of The Occult, p. 31, Faith Publishing Company, ISBN 1-880033-24-0

- ^ "Angels and Demons – Facts not Fiction". fathercorapi.com. Archived from the original on 2004-04-05.

- ^ Augustine of Hippo. "Of the Opinion of the Platonists, that the Souls of Men Become Demons When Disembodied". City of God, ch. 11.

- ^ a b c Irving M. Zeitlin (19 March 2007). The Historical Muhammad. Polity. p. 59. ISBN 978-0-7456-3999-4.

- ^ Amira El-Zein Islam, Arabs, and Intelligent World of the Jinn Syracuse University Press 2009 ISBN 9780815650706 page 44

- ^ Smith, Peter (2008). An Introduction to the Baha'i Faith. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 112. ISBN 978-0-521-86251-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ A.E. Waite, The Book of Black Magic, (Weiser Books, 2004).

- ^ The Encyclopedia of Witches, Witchcraft and Wicca – page 95, Rosemary Guiley – 2008

- ^ Freud (1950, 65), quoting Wundt (1906, 129).

- ^ Freud, S. (1950). Totem and Taboo. London:Routledge

- ^ Peck, M.S. (1983). People of the Lie: The Hope For Healing Human Evil

- ^ Peck, M.S. (2005). Glimpses of the Devil: A Psychiatrist's Personal Accounts of Possession, Exorcism, and Redemption.

- ^ The exorcist, an interview with M. Scott Peck by Rebecca Traister published in Salon

- ^ a b The devil you know, National Catholic Reporter, April 29, 2005, a commentary on Glimpses of the Devil by Richard Woods

- ^ The Patient Is the Exorcist, an interview with M. Scott Peck by Laura Sheahen

- ^ Dominican Newsroom Archived August 29, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "RichardWoodsOP.net". RichardWoodsOP.net. Retrieved 2014-03-12.

- ^ Haarman, Susan (2005-10-25). "BustedHalo.com". BustedHalo.com. Retrieved 2014-03-12.

- ^ SN Chiu, “Historical, Religious, and Medical Perspective of Possession Phenomenon” in Hong Kong Journal of Psychiatry, (East Asian Archives of Psychiatry, 2000).

- ^ “Demon” in Britannica Concise Encyclopedia,

Citations

- Freud, Sigmund (1950). Totem and Taboo:Some Points of Agreement between the Mental Lives of Savages and Neurotics. trans. Strachey. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-00143-3.

- Wundt, W. (1906). Mythus und Religion, Teil II (Völkerpsychologie, Band II). Leipzig.

- Castaneda, Carlos (1998). The Active Side of Infinity. HarperCollins NY ISBN 978-0-06-019220-4

Further reading

- Oppenheimer, Paul (1996). Evil and the Demonic: A New Theory of Monstrous Behavior. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-6193-9.

- Catholic

- Baglio, Matt (2009). The Rite: The Making of a Modern Exorcist. Doubleday Religion. ISBN 0-385-52270-3.

- Amorth, Fr. Gabriele (1999). An Exorcist Tells His Story. Ignatius Press. ISBN 0-89870-710-2.

External links

- Catechism of the Catholic Church: Hyperlinked references to demons in the online Catechism of the Catholic Church

- Dictionary of the History of Ideas: Demonology

- Profile of William Bradshaw, American demonologist Riverfront Times, St. Louis, Missouri, USA. August 2008.