Fanny Hill

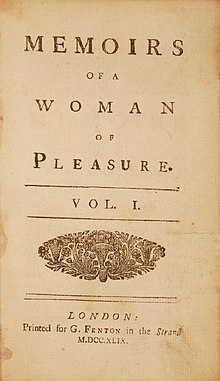

One of earliest editions, 1749 (M.DCC.XLIX) | |

| Author | John Cleland |

|---|---|

| Original title | Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Erotic novel |

Publication date | November 21, 1748; February 1749 |

| Publication place | United Kingdom |

| Media type | Print (Hardback & Paperback) |

| ISBN | 0-14-043249-3 |

| OCLC | 13050889 |

| 823/.6 19 | |

| LC Class | PR3348.C65 M45 1985b |

Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure (popularly known as Fanny Hill) is an erotic novel by English novelist John Cleland first published in London in 1748. Written while the author was in debtors' prison in London,[1][2] it is considered "the first original English prose pornography, and the first pornography to use the form of the novel".[3] One of the most prosecuted and banned books in history,[4] it has become a synonym for obscenity.[5]

Publishing history

The novel was published in two installments, on November 21, 1748 and February 1749, respectively, by "G. Fenton", actually Fenton Griffiths and his brother Ralph.[6] Initially, there was no governmental reaction to the novel, and it was only in November 1749, a year after the first instalment was published, that Cleland and Ralph Griffiths were arrested and charged with "corrupting the King's subjects." In court, Cleland renounced the novel and it was officially withdrawn.

However, as the book became popular, pirate editions appeared. It was once suspected that the sodomy scene near the end that Fanny witnesses in disgust was an interpolation made for these pirated editions, but as Peter Sabor states in the introduction to the Oxford edition of Memoirs (1985), that scene is present in the first edition (p. xxiii). In the 19th century, copies of the book sold underground in the UK, the US and elsewhere.[7]

The book eventually made its way to the United States. In 1821, in the first known obscenity case in the United States, a Massachusetts court outlawed Fanny Hill. The publisher, Peter Holmes, was convicted for printing a "lewd and obscene" novel. Holmes appealed to the Massachusetts Supreme Court. He claimed that the judge, relying only on the prosecution's description, had not even seen the book. The state Supreme Court wasn't swayed. The Chief Justice wrote that Holmes was "a scandalous and evil disposed person" who had contrived to "debauch and corrupt" the citizens of Massachusetts and "to raise and create in their minds inordinate and lustful desires."

Mayflower (U.K.) edition

This section may be too long and excessively detailed. (February 2014) |

It was not until 1963, after the failure of the British obscenity trial of Lady Chatterley's Lover in 1960 that Mayflower Books, run by Gareth Powell, published an unexpurgated paperback version of Fanny Hill. The police became aware of the 1963 edition a few days before publication, after spotting a sign in the window of the Magic Shop in Tottenham Court Road in London, run by Ralph Gold. An officer went to the shop and bought a copy and delivered it to the Bow Street magistrate Sir Robert Blundell, who issued a search warrant. At the same time, two officers from the vice squad visited Mayflower Books in Vauxhall Bridge Road to determine whether quantities of the book were kept on the premises. They interviewed the publisher, Gareth Powell, and took away the only five copies there. The police returned to the Magic Shop and seized 171 copies of the book, and in December Ralph Gold was summonsed under section 3 of the Obscenity Act. By then, Mayflower had distributed 82,000 copies of the book, but it was Gold rather than Mayflower or Fanny Hill who was being tried, although Mayflower covered the legal costs. The trial took place in February 1964. The defence argued that Fanny Hill was a historical source book and that it was a joyful celebration of normal non-perverted sex—bawdy rather than pornographic. The prosecution countered by stressing one atypical scene involving flagellation, and won. Mayflower decided not to appeal.

The Mayflower case had highlighted the growing disconnect between the obscenity laws and the social realities of late 1960s Britain, and was instrumental in shifting views to the point where in 1970 an unexpurgated version of Fanny Hill was once again published in Britain.

First U.S. edition

In 1963, Putnam published the book in the United States under the title John Cleland's Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure. This edition was also immediately banned for obscenity in Massachusetts, after a mother complained to the state’s Obscene Literature Control Commission.[7] The publisher's challenge to the ban went up to the Supreme Court. In a landmark decision in 1966, the United States Supreme Court ruled in Memoirs v. Massachusetts that Fanny Hill did not meet the Roth standard for obscenity.

The art historian Johann Joachim Winckelmann recommended the work in a letter for "its delicate sensitivities and noble ideas" expressed in "an elevated Pindaric style".[8]

Illustrations

Editions of the book have frequently featured illustrations, but they have often been of poor quality.[9] An exception to this is the set of mezzotints, probably designed by the artist George Morland and engraved by his friend John Raphael Smith that accompanied one edition.

Plot

This article's plot summary may be too long or excessively detailed. (February 2014) |

The book is written as a series of letters from Frances "Fanny" Hill to an unknown woman, with Fanny justifying her life-choices to this individual. At the beginning of her tale, Fanny Hill is a young girl with a rudimentary education living in a small village near Liverpool. Shortly after she turns 15, both her parents die. Esther Davis, a girl from Fanny's village who has since moved to London, convinces Fanny to move to the city as well, but Esther abandons Fanny once they arrive. Fanny hopes to find work as a maid, and is hired by Mrs. Brown, a woman she believes to be a wealthy lady. Mrs. Brown is in fact a madam (pimp) and intends the innocent Fanny to work for her as a prostitute. Mrs. Brown's associate, Phoebe Ayers, shares a bed with Fanny and introduces her to sexual pleasure. Mrs. Brown plans to sell Fanny's virginity to an ugly old man, but Fanny is repulsed by the man and struggles with him. She is saved from rape by Mrs. Brown's maid. After this ordeal, Fanny falls into a fever for several days. Mrs. Brown, realizing that Fanny's virginity is still intact, decides to sell Fanny's sexual favors to the exceedingly rich Lord B., who is due to arrive in a few weeks.

Fanny spies on Mrs. Brown having sex with a large, muscular man. She talks to Phoebe, who assures her that it is possible for a young girl to have sex with a well-endowed man. She takes Fanny to spy on another prostitute, Polly Phillips, having sex with a handsome and well-endowed young Genovese merchant. Afterward, Phoebe and Fanny engage in mutual masturbation and Fanny looks forward to her first time having sex with a man.

Soon afterward, Fanny meets Charles, a 19-year-old wealthy nobleman, and they fall in lust instantly. Charles helps Fanny escape the brothel the next day, and takes her to his flat at St. James's, London, and introduces her to his landlady, Mrs. Jones. For many months, Charles visits Fanny almost daily to have sex. Fanny works hard to become more educated and urbane. After eight months, Fanny becomes pregnant. Three months later, Charles mysteriously disappears. Mrs. Jones learns that Charles' father has kidnapped Charles and sent him to the South Seas to win a fortune. Upset by the news that Charles will be gone for at least three years, Fanny miscarries and falls ill. She is nursed back to health by Mrs. Jones, but sinks into a deep depression.

Mrs. Jones tells Fanny that the now-16-year-old girl must work as a prostitute for her, and introduces her to Mr. H, a tall, rich, muscular, hairy-chested man. Fanny unwittingly drinks an aphrodisiac, and has sex with Mr. H. She concludes that sex can be had for pleasure, not just love. Mr. H puts Fanny up in a new apartment and begins paying her with jewels, clothes, and art. After seven months, Fanny discovers that Mr. H has been having sex with her maid, so she resolves to seduce Will, Mr. H's 19-year-old servant. A month later, Mr. H catches Fanny having sex with Will, and stops supporting her.

Fanny is taken in by Mrs. Cole, the mistress of one of Mr. H's friends, who also happens to run a brothel in the Covent Garden neighborhood of London. Fanny meets three other prostitutes, who are also living in the house:

- Emily, a blonde girl in her early 20s who ran away at the age of 14 from her country home to London. She met a 15-year-old boy who, being sexually experienced, engaged in sexual intercourse with virgin Emily. Although the two lived together a short time, Emily became a street prostitute for a few years before being taken in by Mrs. Cole.

- Harriet, a brunette and an orphan raised by her aunt, had her first sexual experience with the son of Lord N., a nobleman whose estate adjoined her relative's.

- Louisa, the bastard daughter of a cabinetmaker and a maid who entered puberty at a very young age and began engaging in extensive masturbation. While visiting her mother in London, Louisa began masturbating in a booked bedroom. The lady who had rented the rooms' 19-year-old son caught her and made love to the 13-year-old girl. Louisa spent the next few years having sex with as many men as she could and turned to prostitution as a means of satisfying her lust.

A short time later, Fanny participates in an orgy with the three girls and four rich noblemen. Fanny and her young nobleman begin a relationship, but it ends after a few months because the young man moves to Ireland. Mrs. Cole next introduces Fanny to Mr. Norbert, an impotent alcoholic and drug addict who engages in rape fantasies with prostitutes. Unhappy with Mr. Norbert's impotence, Fanny engages in anonymous sex with a sailor in the Royal Navy. However, Mr. Norbert soon dies. Mrs. Cole then introduces Fanny to Mr. Barville, a rich, young masochist who requires whipping to enjoy sex. After a short affair, Fanny begins a sexual relationship with an elderly customer who becomes sexually aroused by caressing her hair and biting the fingertips off her gloves. After this ends, Fanny enters a period of celibacy.

Emily and Louisa go to a drag ball, where Emily meets a bisexual young man who believes Emily is a male. When he finds out that she is actually a female, he has sex with Emily in his carriage. Fanny is confused by her first encounter with male homosexuality. Shortly after this incident, Fanny takes a ride in the country and ends up paying for a room at a public tavern after her carriage breaks down. She spies on two young men engaging in anal sex in the next room. Startled, she falls off a stool and knocks herself unconscious. Although the two men have left, she still rouses the villagers to try to hunt the two men down and punish them.

Some weeks later, Fanny watches as Louisa seduces the teenage son of a local woman. The boy, clearly a virgin, engages in somewhat violent, brutal sex several times with Louisa. Louisa leaves Mrs. Cole's brothel a short time later after falling in love with another young man. Emily and Fanny are then invited by two gentleman to a country estate. They swim in a stream, and the two men have sex with the girls for several hours. Emily's parents soon find their daughter, and (unaware of her career as a prostitute) ask her to come home again. She accepts.

Mrs. Cole retires, and Fanny starts living off her savings. One day she encounters a man of 60 who looks 45 due to his lifestyle. The man falls in love with Fanny but treats her like his daughter. He dies and leaves his small fortune to her. Now 18 years old, Fanny uses her new wealth to try to locate Charles. She learns that he disappeared two and a half years ago after reaching the South Seas. Several months later, a despondent Fanny takes a trip to see Mrs. Cole (who had retired to Liverpool), but a storm forces her to stop at an inn along the way, where she runs into Charles: He had come back to England but was shipwrecked on the Irish coast. Fanny and Charles get a room together and make love several times. Fanny tells Charles everything about her life of vice, but he forgives her and asks Fanny to marry him, which she does.

Excerpt

"...and now, disengag’d from the shirt, I saw, with wonder and surprise, what? not the play-thing of a boy, not the weapon of a man, but a maypole of so enormous a standard, that had proportions been observ’d, it must have belong’d to a young giant. Its prodigious size made me shrink again; yet I could not, without pleasure, behold, and even ventur’d to feel, such a length, such a breadth of animated ivory! perfectly well turn’d and fashion’d, the proud stiffness of which distended its skin, whose smooth polish and velvet softness might vie with that of the most delicate of our sex, and whose exquisite whiteness was not a little set off by a sprout of black curling hair round the root, through the jetty sprigs of which the fair skin shew’d as in a fine evening you may have remark'd the clear light ether through the branchwork of distant trees over-topping the summit of a hill: then the broad and blueish-cast incarnate of the head, and blue serpentines of its veins, altogether compos’d the most striking assemblage of figure and colours in nature. In short, it stood an object of terror and delight.

"But what was yet more surprising, the owner of this natural curiosity, through the want of occasions in the strictness of his home-breeding, and the little time he had been in town not having afforded him one, was hitherto an absolute stranger, in practice at least, to the use of all that manhood he was so nobly stock’d with; and it now fell to my lot to stand his first trial of it, if I could resolve to run the risks of its disproportion to that tender part of me, which such an oversiz’d machine was very fit to lay in ruins."

Literary and film adaptations

Because of the book's notoriety (and public domain status), numerous adaptations have been produced. Some of them are:

- Fanny, Being the True History of the Adventures of Fanny Hackabout-Jones (1980) (a retelling of 'Fanny Hill' by Erica Jong purports to tell the story from Fanny's point of view, with Cleland as a character she complains fictionalized her life).

- Fanny Hill (USA/West Germany, 1964), starring Letícia Román, Miriam Hopkins, Ulli Lommel, Chris Howland; directed by Russ Meyer, Albert Zugsmith (uncredited)[10]

- The Notorious Daughter of Fanny Hill (USA, 1966), starring Stacy Walker, Ginger Hale; directed by Peter Perry (Arthur Stootsbury).

- Fanny Hill (Sweden, 1968), starring Diana Kjær, Hans Ernback, Keve Hjelm, Oscar Ljung; directed by Mac Ahlberg[11]

- Fanny Hill (West Germany/UK, 1983), starring Lisa Foster, Oliver Reed, Wilfrid Hyde-White, Shelley Winters; directed by Gerry O'Hara[12]

- Paprika (Italy, 1991), starring Debora Caprioglio, Stéphane Bonnet, Stéphane Ferrara, Luigi Laezza, Rossana Gavinel, Martine Brochard and John Steiner; directed by Tinto Brass.[13]

- Fanny Hill (USA, 1995), directed by Valentine Palmer.[14]

- Fanny Hill (Off-Broadway Musical, 2006), libretto and score by Ed Dixon, starring Nancy Anderson as Fanny.

- Fanny Hill (UK, 2007), written by Andrew Davies for the BBC and starring Samantha Bond and Rebecca Night.[15]

References in popular culture

References in literary works

- 1965: In Harry Harrison's novel Bill, the Galactic Hero, the titular character is stationed on a starship named Fanny Hill.

- 1966: In Lita Grey's book, My Life With Chaplin, she claims that Charlie Chaplin "whispered references to some of Fanny Hill's episodes" to arouse her before making love.

- 1984: In the book Frost at Christmas by R. D. Wingfield, the vicar has a copy of Fanny Hill hidden in his trunk amongst other dirty books.

- 1993: In Diana Gabaldon's novel Voyager, in a scene set in 1758, the male protagonist Jamie Fraser reads a borrowed copy of Fanny Hill.

- 1999: In a portrait that appears in the first volume of Alan Moore's The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, Fanny Hill is depicted as a member of the 18th century version of the League. She also appears more prominently in "The Black Dossier" as a member of Gulliver's League, as well as a "sequel" to the original Hill novel, complete with illustrations by Kevin O'Neill. The setting of her involvement with the League begins with her divorce from Charles after he is caught in the act in a brothel kept by former League member Amber St. Clare, and is shown to have been sexually involved with both Gulliver and Captain Clegg nearly 40 years before the second League was founded. She doesn't age as an effect of her stay at Horselberg. This version has apparently pursued a lesbian relationship with a character named Venus (who seems to be an amalgamation of the various versions of the Goddess of love in literature) for at least a century and a half as of the Black Dossier and in contrast to the novel's relationships this one seems to be enduring.

References in film, television, musical theatre and song

- 1965: The novel is mentioned in Tom Lehrer's song "Smut" in the album That Was the Year That Was

- 1968 (April) version of Yours, Mine, and Ours, Henry Fonda's character, Frank Beardsley, gives some fatherly advice to his stepdaughter. Her boyfriend is pressuring her for sex and Frank says boys tried the same thing when he was her age. When she tries to tell him that things are different now he observes, "I don't know, they wrote Fanny Hill in 1742 [sic] and they haven't found anything new since."

- 1968 (December): A tongue-in-cheek reference appears in the David Niven, Lola Albright film The Impossible Years. In one scene the younger daughter of Niven's character is seen reading Fanny Hill, whereas his older daughter, Linda, has apparently graduated from Cleland's sensationalism and is seen reading Sartre instead.

- 23 November 1972: An episode of Monty Python's Flying Circus, fittingly titled "The War Against Pornography", featured a sketch that parodied the exploitation of sex on television for ratings, in which John Cleese played the narrator of a documentary on molluscs who adds highly sexualized imagery to maintain his audience's interest; when discussing the clam, he describes it as "a cynical, bed-hopping, firm-breasted, Rabelaisian bit of seafood that makes Fanny Hill look like a dead Pope!"

- 1974: In a segment in the film The Groove Tube, children's TV show host Koko the Clown (Ken Shapiro) asks the children in his audience to send their parents out of the room during "make believe time." He then proceeds to secretly read an excerpt from page 47 of Fanny Hill in response to a viewer's request.[16]

- 1975: In the M*A*S*H season 4 episode "The Price of Tomato Juice",[17] Radar thanks Sparky for sending the book Fanny Hill but says the last chapter was missing and asks "Who did it?" He repeats back Sparky's answer: "Everybody".

- In the season 4 episode "Some 38th Parallels", Hawkeye tells Colonel Potter that he was reading Fanny Hill in the back of a truck on top of a pile of rotting peaches, and adds that when the truck hit a bump he was "in heaven".

- In the season 6 episode "Major Topper", Hawkeye tells a person knocking on the door to go read Fanny Hill.

- The 2006-07 Broadway musical Grey Gardens has a comedic reference to Fanny Hill in the first act. Young Edith Bouvier Beale (aka "little Edie") has just been confronted about a rumour of promiscuity that her mother, Mrs. Edith Bouvier Beale (aka "Big Edie") told her fiancé. Little Edie was allegedly engaged to Joseph P. Kennedy, Jr., in 1941 until he discovered that Little Edie may have been sexually acquainted with other men before him. Little Edie implores Joe Kennedy not to break off the engagement and to wait for her father to come home and rectify the situation, vouching for her reputation. The musical line that Little Edie sings in reference to Fanny Hill is: "Girls who smoke and read Fanny Hill / Well I was reading De - Toc - que - ville"

See also

References

- ^ Wagner, "Introduction," in Cleland, Fanny Hill, 1985, p. 7.

- ^ Lane, Obscene Profits: The Entrepreneurs of Pornography in the Cyber Age, 2000, p. 11.

- ^ Foxon, Libertine Literature in England, 1660-1745, 1965, p. 45.

- ^ Browne, Ray Broadus; Browne, Pat (2001). The Guide to United States Popular Culture. Popular Press. p. 273. ISBN 978-0-87972-821-2.

- ^ Kendrick, Walter M. (1987). The Secret Museum Pornography in Modern Culture. University of California Press. p. 209. ISBN 978-0-520-20729-5.

- ^ Roger Lonsdale, "New attributions to John Cleland", The Review of English Studies 1979 XXX(119):268-290 doi:10.1093/res/XXX.119.268

- ^ a b Graham, Ruth. "How 'Fanny Hill' stopped the literary censors". Boston Globe. Boston Globe. Retrieved 9 October 2014.

- ^ Winckelmann, Briefe, H. Diepolder and W. Rehm, eds., (1952-57) vol. II:111 (no. 380) noted in Thomas Pelzel, "Winckelmann, Mengs and Casanova: A Reappraisal of a Famous Eighteenth-Century Forger" The Art Bulletin, 54.3 (September 1972:300-315) p. 306 and note.

- ^ Hurwood, p.179

- ^ Fanny Hill (1964) at IMDb

- ^ Fanny Hill (1968) at IMDb

- ^ Fanny Hill (1983) at IMDb

- ^ Paprika at IMDb

- ^ Fanny Hill (1995) at IMDb

- ^ Article from The Guardian

- ^ Fédération française des ciné-clubs (1975). Cinéma. Vol. 200–202. Fédération française des ciné-clubs. p. 300.

- ^ MashEpisodeGuide

Bibliography

- Browne, Ray Broadus; Browne, Pat (2001). The Guide to United States Popular Culture. Popular Press. ISBN 978-0-87972-821-2.

- Cleland, John (1985). Fanny Hill Or Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure. Penguin Books Limited. ISBN 978-0-14-043249-7.

- Foxon, David. Libertine Literature in England, 1660-1745. New Hyde Park: University Books, 1965.

- Hurwood, Bernhardt J. The Golden age of erotica, Tandem, ISBN 0-426-02030-8, 1969.

- Kendrick, Walter M. (1987). The Secret Museum Pornography in Modern Culture. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-20729-5.

- Lane, Frederick S. (2000). Obscene Profits The Entrepreneurs of Pornography in the Cyber Age. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-92096-4.

- Sutherland, John (1983). Offensive Literature Decensorship in Britain, 1960-1982. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-389-20354-4.

- Cleland, John (1985). Fanny Hill Or Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure. Penguin Books Limited. ISBN 978-0-14-043249-7.

External links

- Fanny Hill: Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure at Project Gutenberg

- Charles Dickens's Themes A surprising allusion to Fanny Hill in Dombey and Son.

- BBC TV Adaptation First Broadcast October 2007

- The Notorious Daughter of Fanny Hill (1966) at DBCult Film Institute