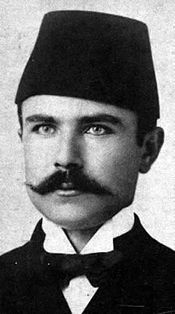

Fares al-Khoury

Fares al-Khoury | |

|---|---|

| فارس الخوري | |

| |

| 19th Prime Minister of Syria | |

| In office October 14, 1944 – October 1, 1945 | |

| President | Shukri al-Quwatli |

| Preceded by | Saadallah al-Jabiri |

| Succeeded by | Saadallah al-Jabiri |

| In office November 3, 1954 – February 13, 1955 | |

| President | Hashim al-Atassi |

| Preceded by | Said al-Ghazzi |

| Succeeded by | Sabri al-Assali |

| Speaker of the Parliament of Syria | |

| In office November 21, 1938 – July 8, 1939 | |

| Preceded by | Hashim al-Atassi |

| Succeeded by | Fares al-Khoury |

| In office August 17, 1943 – October 17, 1944 | |

| Preceded by | Fares al-Khoury |

| Succeeded by | Saadallah al-Jabiri |

| In office September 16, 1945 – October 22, 1946 | |

| Preceded by | Saadallah al-Jabiri |

| Succeeded by | Fares al-Khoury |

| In office September 27, 1947 – March 31, 1949 | |

| Preceded by | Fares al-Khoury |

| Succeeded by | Rushdi al-Kikhya |

| 1st Syrian Permanent Representative to the United Nations | |

| In office 1946–1948 | |

| Preceded by | office established |

| Succeeded by | Farid Zeineddine |

| Personal details | |

| Born | November 20, 1877[citation needed] Kfeir, Hasbaya, Ottoman Syria (present day Lebanon) |

| Died | January 2, 1962 (aged 84) Damascus, Syria |

| Political party | National Bloc |

| Spouse | Asma'a Gabriel Eid |

| Relatives | Fayez al-Khoury, brother Suhail al-Khoury, son Colette Khoury, granddaughter |

Fares al-Khoury (Arabic: فارس الخوري, romanized: Fāris al-Khūrī) (November 20,[citation needed] 1877 – January 2, 1962[1]) was a Syrian statesman, minister, prime minister, speaker of parliament, and father of modern Syrian politics. Faris Khoury went on to become prime minister of Syria from October 14, 1944, to October 1, 1945, and from October 1954 to February 13, 1955. Fares Khoury's position as prime minister is, as of 2017, the highest political position a Syrian Christian has ever reached. Khoury's electoral popularity was due in part to his staunch secularist and nationalist policies. As a die-hard Syrian nationalist, Khoury never compromised on his principles and was resolutely against pan-Arabism and the ill-fated union between Syria and Egypt. Khoury opposed the short-lived union between Nasser's Egypt and republican Syria, the United Arab Republic. Through it all Faris Khoury served his country for almost 50 years. He was the grandfather of noted Syrian novelist Colette Khoury.

Early years

[edit]Fares Khoury was born in Kfeir in the Hasbaya District in modern-day Lebanon to a Greek Orthodox Christian[2] family that, according to Faris' own memoirs, had originally came from the village of Ayn Halya in Kaza Al-Zabadani.[3][4][5] The family eventually converted to Presbyterianism. Faris studied at the American University of Beirut, at the time called Syrian Protestant College.[6] He started his career as an instructor at AUB and became involved in Al-Fatat, the leading anti-Ottoman movement, after its creation in Paris in 1911. Khoury became the Christian member of the Ottoman Parliament representing Damascus in 1914 but resigned in 1916.[7] In May 1916 Khoury agreed to assist Michel Sursock, a wartime profiteer, in requisitioning grain from farmers in the Hawran.[8] Also 1916, Khoury joined the Arab resistance and promised to support the Arab Revolt, launched from Mecca by Sharif Husayn. His connections with Husayn, the prime nationalist of his era, resulted in his arrest and trial by a military tribunal in Aley. After King Faisal's arrival and liberation of Syria, Khoury pledged allegiance to King Faisal, the newly proclaimed King of Syria, by the Syrian people. On September 18, 1918, Khoury created a preliminary government with a group of notables in Damascus, spearheaded by Prince Sa’id al-Jaza’iri. Khoury then became Minister of Finance in the new Syrian cabinet of Prime Minister Rida Pasha al-Rikabi. His post was renewed by Prime Minister Hashim al-Atassi in May 1920. He held this position until King Faisal was dethroned and the French Colonial forces imposed their mandate on Syria in July 1920. Khoury laid the groundwork for the Syrian Ministry of Finance, created its infrastructure, distributed its administrative duties, formulated its laws, and handpicked its staff. In 1923, he helped found Damascus University and along with a group of veteran educators, translated its entire curriculum from Ottoman Turkish into Arabic.

Later years

[edit]In 1925 Khoury joined Abd al-Rahman Shahbandar[9] to found the People's Party, of which he became vice-president. Minister of Education from April to July 1926, he was elected member of the Syrian Constituent Assembly in 1928, then elected to the Syrian Parliament in 1932, reelected in 1936 (and president of the Parliament till 1939) and 1943 (and again president of the Parliament till 1944). He was a member of the Syrian delegation that negotiated the Franco-Syrian Treaty in Paris in 1936.

Foundation of the UN

[edit]Fares Khoury was the first Syrian statesman to visit the United States and represent his country in 1945 at the inauguration of the UN. Syria was one of the original 53 founding members of the United Nations. As the head of Syria's delegation in San Francisco, Faris al-Khoury's superb oratory and astuteness made a strong impression in front of world leaders. After hearing Khoury's eloquent speech, a US diplomat remarked: "It is impossible for a country with men like these, to be occupied!" [10]

One of the amazing stories in the history of the United Nations is when Faris Al-Khoury sat on France's chair instead of Syria's, After a few minutes, the French representative to the UN approached Faris and asked him to leave the chair, but Faris ignored the Frenchman and just looked at his watch, a couple of minutes later, the Frenchman angrily asked Faris to leave immediately, but Faris kept on ignoring the Frenchman and just staring at his watch, After 25 minutes of sitting in France's chair, Faris left the chair and said to the French representative: "You could not bear watching me sitting in your chair for a mere 25 minutes, Your country has occupied mine for more than 25 years, hasn't the time of your troops departure come yet?". It is worth noting that the process of Syria's independence started in this same UN session. [citation needed]

Political career

[edit]He became Prime Minister from October 14, 1944, till October 1, 1945, then again president of the parliament till the military coup of Husni al-Za'im who dissolved it in April 1949. After free elections in October 1954, he returned as Prime Minister from October 25, 1954, till February 13, 1955, when his pro-Western government, hostile to a union with Egypt, was toppled by the parliament.

Death

[edit]In his old age, Fares al-Khoury spent more time with his wife, child, and three grandchildren, Fares Jr, Colette, and Samer. He continued to travel to attend annual law conventions in Switzerland, until he fractured his leg and was forced to stay at home for the final two years of his life. On January 2, 1962, the former Syrian prime minister died in Damascus, at the age of 84, ending a career that spanned over 50 years in Syria’s political sphere. He received presidential honors at his funeral as one of the founders of the Syrian Republic, unlike any prime minister before or after him. Making a statement even in death, Muslim community leaders were allowed to recite the Quran during the condolence service. Suheil al-Khury accepted this rare act to show how secular his father had been, and how close he had been to both Muslims and Christians.[11] Faris al-Khoury's death came three months after the dissolution of the United Arab Republic between Egypt and Syria (1958–1961) during which he was an active political opponent.

Legal opinions

[edit]As a typical Syrian nationalist, he considered the territorial transfer of Hatay Province to Turkey by the French government as illegal under international law.[12] For that reason, he also opposed the proposal to declare every unprovoked invasion by armed gangs of another country as criminal under international law, claiming that such gangs often served interests of national liberation of certain territories.[13] However, he considered the refusal of government parties to a dispute to submit to UN Security Council resolutions as an international crime.[14]

References

[edit]- ^ Moubayed, Sami M. (2006). Steel & Silk: Men and Women who Shaped Syria 1900-2000. Cune Press. ISBN 9781885942418.

- ^ Provence, Michael (2005). The Great Syrian Revolt and the Rise of Arab Nationalism. University of Texas Press. p. 85. ISBN 0-292-70680-4.

- ^ فارس عن نفسه قال ان اسم والده يعقوب بن جبور بن يعقوب بن ابراهيم الخوري . وقد اخبره جده جبور عن اسلافه قال : جاء جدنا الاكبر الخوري جرجس ابو رزق الى كفير حاصبيا مع اخيه عبد الله من قضاء الزبداني ومعها عائلات ابي جمره وخلف والحاج وغيرها

- ^ "مذكرات فارس خوري بخط يده في "المضحك المبكي" ..اصله .. والده وجده .. دينه ومذهبه ..؟". syria.news. Retrieved 2024-02-11.

- ^ عباس, عبد الهادي أحمد. "الخوري (فارس-)". الموسوعة العربية. Retrieved 2024-02-11.[dead link]

- ^ al-Bustani, Butrus (2019-04-30). The Clarion of Syria: A Patriot's Call against the Civil War of 1860. Univ of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-29943-6.

- ^ Yazıcı, Sibel (2018). Osmanlı Meclis-i Mebusanı ve Faaliyetleri (1914-1918) (PDF) (Ph.D.) (in Turkish). Afyon Kocatepe Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstütüsü Tarih Anabilim Dalı. p. 24. Retrieved 8 June 2021.

- ^ Fawaz, Leila Tarazi (2014) a land of aching hearts : the Middle East in the Great War Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-73549-1. p.122

- ^ "Abd al-Rahman Shahbandar". answers.com.

- ^ Moubay, Samy (24 December 2007). "Good Christians, and Orientalists to the Bone". The Washington Post.

- ^ "The story of Asma and Fares". Forward Magazine. February 2009. Archived from the original on 2012-02-19. Retrieved 2009-03-13.

- ^ Yearbook of the ILC, 1950, vol. 1. p. 77

- ^ Yearbook of the ILC, 1950, vol. 1, pp. 119, 169

- ^ Yearbook of the ILC, 1950, vol. 1, p. 168

- 1877 births

- 1962 deaths

- People from Hasbaya

- Syrian Christians

- Syrian nationalists

- Syrian critics of religions

- Prime ministers of Syria

- 20th-century Syrian politicians

- Arab people from the Ottoman Empire

- American University of Beirut alumni

- Syrian ministers of finance

- Syrian ministers of education

- Speakers of the People's Assembly of Syria

- Permanent Representatives of Syria to the United Nations

- National Bloc (Syria) politicians

- People's Party (Syria) politicians

- Critics of Arab nationalism

- Al-Khoury family