Fixes that fail

Fixes that fail is a system archetype that in system dynamics is used to describe and analyze a situation, where a fix effective in the short-term creates side effects for the long-term behaviour of the system and may result in the need of even more fixes.[1] This archetype may be also known as fixes that backfire[2] or corrective actions that fail.[3] It resembles the Shifting the burden archetype.[4]

Description

In a "fixes that fail" scenario the encounter of a problem is faced by a corrective action or fix that seems to solve the issue. However, this action leads to some unforeseen consequences. They form then a feedback loop that either worsens the original problem or creates a related one.[2][3]

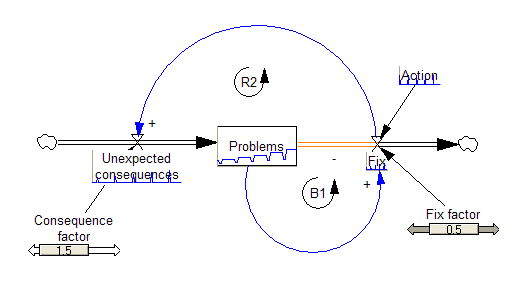

In system dynamics this is described by a circles of causality (Fig. 1) as a system consisting of two feedback loops. One is the balancing feedback loop B1 of the corrective action, the second is the reinforcing feedback loop R2 of the unintended consequences. These influence the problem with a delay and therefore make it difficult to recognize the source of the new rise of the problem.[1]

Representation of the long-term disadvantages of the scenario can be seen on Fig. 2. Although the symptoms go through a decrease when fixes are applied, the overall crisis threshold rises.[4][5]

A representation with a stock and flow diagram of this archetype is on Fig. 3.

The fix influences the amount of problems present in the system proportionally to the fix factor and the problems to be resolved. When activated by the action variable, the fix lowers the problems, thus creating a balancing loop. However, each fix also starts a delayed consequence which adds to the problems proportionally to the consequence factor and the fix applied. Combined, these create a growing amount of problems to be dealt with.

Uses

As an archetype, it helps to gain insight into patterns that are present in the system and thereby also give the tools to change these patterns. In the case of "Fixes that fail", the warning sign is a problem which reappears although fixes were applied. It is crucial to recognize that the fix only adds to the overall deteriorating state and does not solve the problem. To identify this pattern, it is needed to consider a connection between the symptoms and the fixes we apply to solve them, which can be very difficult to do.[4] In management this can be present as a "hero-scapegoat" cycle. While the manager who applied the fix gets promoted for diminishing the problem. A new manager must face the returning problem symptom and may be punished for failing to do his job. Then a new hero is found who temporarily solves the problem symptoms. The delay of the reinforcing loop makes it difficult to recognize the causal relation between the fix applied to the symptoms and the new problems arising. What then seems to be a series of successes in short-term then are steps towards failure on the long-term.[5]

Some typical ways of thinking associated with the pattern are:

- "It always seemed to work before; why isn't it working now?"[1]

- "This is a simple problem and the solution is straightforward."[6]

- "We need to fix this problem now. We can deal with any consequences later." [6]

They can serve as a warning that this archetype is present or will be.

If this pattern is recognized, then there are multiple possibilities how to react, depending on which leverage point is addressed:

- Focus on the long-term and if a fix is inevitably needed, use it only to buy time to work on the long-term remedy.[1]

- Raise awareness of the unintended consequences of the fixes.

- Focus on the underlying problem and not the symptoms.

- Find either a fix without consequences or with limited long-term impact.[2]

- Find a way to measure the intended and also unintended consequences of the solutions by learning also from the past fixes.[4]

- Change the performance review time so that the long-term progress becomes visible.[5]

Examples

A few common examples of the pattern. The situation describes always the starting point to which a fix is applied. This bears then the consequences which are confronted again with a new fix.

- Maximizing ROR[1]

- Situation: A manufacturing company becomes successful with high-performance parts, and its CEO wants to maximize the ROR.

- Fix: Refusal of investment in expensive, new production machines.

- Consequences: The product quality drops and therefore the sales of it.

- Cutting back maintenance[1]

- Situation: The company needs to save money.

- Fix: Decrease the amount of maintenance.

- Consequences: More breakdowns of the equipment, higher costs and cost-cutting pressure.

- Quest for water[6]

- Situation: Farmers are confronted with water shortage.

- Fix: Drilling new wells or making the old ones deeper.

- Consequences: The water table drops.

- Situation: A person can't pay interest (for example on a credit card).

- Fix: Take up a new loan to pay the interest (a new credit card).

- Consequences: There is more interest to pay next time.

- Tax revenue shortage[6]

- Situation: A government is not satisfied with its tax revenues.

- Fix: Increase the cigarette tax to raise more taxes.

- Consequences: Smuggling of cigarettes develops and reduces the amount of taxed cigarettes sold in the country.

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e f Senge, Peter M., "The Fifth Discipline" (1990). ISBN 0-385-26095-4.

- ^ a b c Fixes that backfire Isee systems, 2006. Retrieved 2011-11-01

- ^ a b Flood, Robert L., "Rethinking The Fifth Discipline: learning within the unknowable" (1999). ISBN 0-203-02855-4 p. 19

- ^ a b c d Braun, William (2002). "System archetypes" (pdf). Retrieved 2011-11-01.

- ^ a b c d Kim, Daniel H., "Fixes that Fail: Why Faster is Slower," The Systems Thinker Newsletter, Vol. 10, No. 3 (Apr., 1999)

- ^ a b c d e Fixes That Fail Archetype SystemsWiki, Octobre 2010. Retrieved 2011-11-01